By Robbin Laird

In the United States, we have tweeting Trump and the impeaching House of Representatives; in Europe they have Macronite.

We have had and continue to have a significant deluge of comments on President Trump and his approach to foreign policy with little that has a positive tinge to it; but what about Macronite?

How positive or significant is this for shaping the second creation of the West?

The first creation was lead by the United States after World War II with the laying down of the rules based order; the Post-Cold War period was more or less acting on the belief that the collapse of the Soviet Union allowed those rules of the game to be extended East.

But in fact, little noticed was the rise of 21st century authoritarian capitalist powers who were key anchors of globalization and have woven themselves into the fabric of the liberal democratic societies.

With the 21st century authoritarian powers working to write the rules of the game going forward rather than reinforcing the rules based order, what should and can the Western liberal democracies do?

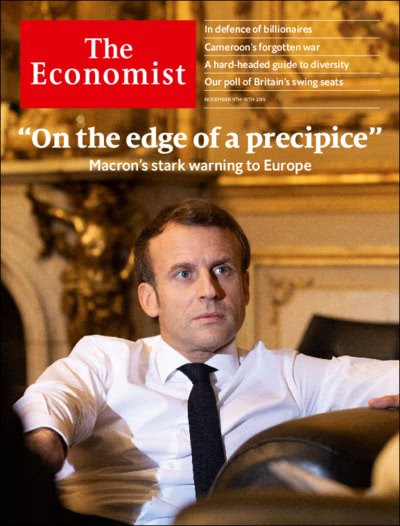

In his recent interview with The Economist, the President of the Republic provided his answer and having done so, he deserves a serious examination of whether or not that resets the effort in a manner that can lead the way ahead.

He certainly has provided a wide ranging analysis of the current situation; but does the Macronite approach going forward provide a realistic way ahead to deal with the current crises?

Let us navigate through his interview and highlight some of his core points to get a sense of how he sees the challenge and gauge his approach to guiding the West to its next phase.

Europe was built on this notion that we would pool the things we had been !ghting over: coal and steel.

It then structured itself as a community, which is not merely a market, it’s a political project.

But a series of phenomena have left us on the edge of a precipice…. A market is not a community.

A community is stronger: it has notions of solidarity, of convergence, which we’ve lost, and of political thought.

What he underscores is the importance of Europe thinking of itself as a community and focus on its common destiny, rather than simply thinking of itself as a trading bloc.

But the challenge facing this core point is rather straightforward: is the European Union with the Commission as its driving force for integration really a custodian for the broader sense of community?

Does Europe need to recast even significantly how the nations can work together to shape community, rather than face a bureaucratic machine which is driving bureaucratically mandated commonality?

And notability, with the expansion of the European Union, there is no way that Western Europe with a 50 year period of working together has as much in common with the “new” states who have been under a 50 year domination by Communism.

This is proving to be a mix which may be more oil and water than providing strands for a single community.

Perhaps there is no single community?

Perhaps we are looking at clusters of states which pursue specific interests in common on particular issues; Rather than thinking of Europe as a community of forced unity.

Maronite is generated by a Europe first policy whereby the Americans are looking elsewhere in the world.

And the current American president is seen to be abandoning the European project.

And with the rise of China, and the preoccupation of the United States with the Pacific, America is focused elsewhere. Of course, there is the largely ignored question of how significant Chinese engagement economically with Europe has become, and whether or not Europe, either individually on the national level or collectively on the European Union level is providing a counter balance to what China has been able to do within Europe itself.

He very clearly focuses on the challenge which the 21st century authoritarian powers pose to Europe while the Americans reduce their commitment to the European project.

So, f!rstly, Europe is gradually losing track of its history; secondly, a change in American strategy is taking place; thirdly, the rebalancing of the world goes hand in hand with the rise—over the last 15 years—of China as a power, which creates the risk of bipolarisation and clearly marginalises Europe.

And add to the risk of a United States/China “G2” the re-emergence of authoritarian powers on the fringes of Europe, which also weakens us very signi!cantly.

This re-emergence of authoritarian powers, essentially Turkey and Russia, which are the two main players in our neighbourhood policy, and the consequences of the Arab Spring, creates a kind of turmoil.

It is hard to disagree with much in his analyses of the world but this is where it gets interesting.

Let us apply some Macronite to the challenges.

His first step: regain military sovereignty.

To do this, he argues for the reenforcement of the European project and having a more realistic assessment of dealing with a “brain dead NATO.”

Europe must become autonomous in terms of military strategy and capability. And secondly, we need to reopen a strategic dialogue, without being naive and which will take time, with Russia. Because what all this shows is that we need to reappropriate our neighbourhood policy, we cannot let it be managed by third parties who do not share the same interests

The problem with this can be put simply — it ignores the reality which he has painted earlier.

There is no common European defense because European defense threats are not seen the same way and there is a reverse trend — clusters of states focusing on their specific approaches within an umbrella set of institutions — NATO and the EU.

Does anyone believe that the Nordic states are waiting for France or Germany to defend them?

Hardly.

They have enhanced their own cooperation and have deepened their working relationships with the United States and the United Kingdom and have done so in large part by embracing the latest US military technologies, something which Macron clearly rails against

But as Secretary Wynne once said — “Being the second best air force in a conflict is not where you want to be.”

And the United States still offers the best opportunity to not be a second best air force, for example.

And as for his working relationship with Berlin, given that Germany has no real commitment to its own direct defense, there is a question of whether France and Germany could defend a central front if challenged by the Russians.

NATO is only as strong as its member states.

This is certainly true and why Article III of the NATO Treaty is the bedrock for any Article V commitments.

But then we are back to a key question: how convergent is French defense policy with other European states to contribute and to manage the common defense?

Is it actually more convergent than is the United States itself?

He notes: I think that the interoperability of NATO works well.

But we now need to clarify what the strategic goals we want to pursue within NATO are.

But the first may be what the European alliances can provide; whereas the second is really left up to the cluster of nations willing to work on specific strategic lines.

Take the case of cyber offense, where France has nothing at all in common with Germany.

Indeed, as a leading French analyst put it to me when I asked him the question: Who are France’s allies in cyber offense?

“The Dutch lead the pack because they recognize that the Russians declared war on them with the shoot-down of the Malaysian airliner. Also crucial are the UK, Sweden and the Baltic states.”

He then goes on to mischaracterize what the Trump Administration is actually doing for European defense.

Even though the current Administration has significantly stepped up its operational commitments to deal with the Russians, this is what Macron has to say.

In the eyes of President Trump, and I completely respect that, NATO is seen as a commercial project. He sees it as a project in which the United States acts as a sort of geopolitical umbrella, but the trade-o$ is that there has to be commercial exclusivity, it’s an arrangement for buying American products. France didn’t sign up for that.

This is an indirect comment getting at the “F-35 threat” to Europe which is treated as strategic as the seizure of Crimea by many French analysts.

And hence we see the brith of the Future Combat System and the coming fighter in 2040.

But as one German analyst put it: “I hope we have agreement with the Russians for avoiding conflict until 2040.”

In my opinion some elements must only be European.

This is where the Macronite impact could be signifiant, if Europe follows the Finnish approach.

Notably with regard to infrastructure, Europe has allowed the 21st century authoritarian powers to own significant infrastructure elements in Europe.

They are not alone.

This can lead to what John Blackburn, the Australian analyst, to a condition where “we are losing without fighting.”

How to control our supply chains and infrastructure to the point whereby the authoritarian powers can not disrupt our capabilities in a conflict is a clear challenge.

And significant focus within Europe on this problem could follow from the Macronite impulse.

Of course, the Finns lead the way on this and not the French.

The underlying idea is that if we’re all linked by business, all will be !ne, we won’t hurt each other. In a way, that the inde!nite opening of world trade is an element of making peace.

Except that, within a few years, it became clear that the world was breaking up again, that tragedy had come back on stage, that the alliances we believed to be unbreakable could be upended, that people could decide to turn their backs, that we could have diverging interests.

And that at a time of globalisation, the ultimate guarantor of world trade could become protectionist.

Major players in world trade could have an agenda that was more an agenda of political sovereignty, or of adjusting the domestic to the international, than of trade.

The question of the future of globalization is clearly a key one to sort through at the second creation.

And here Macron talks both European values and national sovereignty and assumes that the two blend together — but that is precisely the nexus of the challenge — they do not.

To re design globalization to work with trusted partners, to reshape manufacturing, to shorten supply chains, to deal with the political challenge of the 21st century authoritarian states, certainly starts with national solutions, but ones which recognize the semi-sovereign situation in which the modern democratic state finds itself.

Maron highlights the challenge in his interview, but the question is how best to deal with national sovereignty in a semi sovereign world in which 21st century authoritarian powers are on the ascendancy?

And this is his trajectory with regard to one of the key authoritarian powers, Russia.

If we want to build peace in Europe, to rebuild European strategic autonomy, we need to reconsider our position with Russia. That the United States is really tough with Russia, it’s their administrative, political and historic superego. But there’s a sea between the two of them.

It’s our neighbourhood, we have the right to autonomy, not just to follow American sanctions, to rethink the strategic relationship with Russia, without being the slightest bit naive and remaining just as tough on the Minsk process and on what’s going on in Ukraine.

It’s clear that we need to rethink the strategic relationship. We have plenty of reasons to get angry with each other. There are frozen conflicts, energy issues, technology issues, cyber, defence, etc.

What I’ve proposed is an exercise that consists of stating how we see the world, the risks we share, the common interests we could have, and how we rebuild what I’ve called an architecture of trust and security.

And when asked how the Poles and Balts feel about this approach, he highlights that indeed there are “European” differences.

Having a strategic vision of Europe means thinking about its neighbourhood and its partnerships. Which is something we haven’t yet done. During the debate over enlargement, it was clear that we are thinking about our neighbourhood above all in terms of access to the European Union, which is absurd.

Macronite is about driving European solutions to its common neighborhood, but the challenge for France is that the Europe envisaged by the French president may not be the realistic project or outcome.

As former Admiral James Stavridis commented after the release of The Economist interview:

NATO is far from brain dead, but it is suffering from the fallout of centrifugal forces pulling Europe apart. NATO has key missions in deterring Russia, the Arctic, cyber, and the Med — all directly affecting USA.

For the full Economist interview, see the following:

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/11/07/assessing-emmanuel-macrons-apocalyptic-vision

For the first article in this series, see the following:

president-macron-and-edith-piafs-cri-de-coeur-present-at-the-creation-round-2