By Robbin Laird

I have just returned from Berlin.

I attended the International Fighter Conference 2019 and visited Checkpoint Charlie and shared thoughts with German friends of the thirty-year anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall.

Both events had much in common – the Cold War is over but the Russians are back.

And this faces Germany and its trans-Atlantic allies with major challenges in rebuilding their military forces and their over-arching deterrent strategy.

Earlier this year, I visited Munich, Bonn, Hamburg, Frankfort and Berlin, and met with and conducted interviews with a wide range of recently retired Bundeswehr officials, journalists and strategists to discuss the challenge facing both Germany and the Alliance to deal with the new challenges posed by the 21st century authoritarian powers, including conflicts in what are being called, “gray zone” and “hybrid warfare” conflicts.

The nuclear threat clearly remains, and as the European Union and NATO confront internal disagreements as well as differentiated modernization, the challenge will be to ensure that the nations meet their Article III national defense obligations as they come to the table to the defense of their NATO allies in terms of crisis, conflict or war.

This is occurring at a time of profound change in military technologies and the overall nature of the security and defense threats and challenges as well.

For example, the International Fighter Conference 2019 focused on the challenges facing the fighter forces as they adjusted to the new context of multi-domain threats in a full spectrum crisis threat environment.

Much of the fighter conference was a clear recognition that the role of the fighter force was changing significantly in terms of how they would play various roles in a multi-domain force.

This meant that much of their combat focus would be within the changing context of the tailored force packages which would need to operate against discrete and specific threats facing the alliance.

It is about how to shape an effective combat package which can operate within a contested environment and to do so rapidly enough to make a difference.

What this means for any new platforms coming to the combat force that it is crucial that they are the best choices available to deliver the kind of combat capability which can be anticipated in a crisis environment.

It is about having connected platforms which can work together to deliver the combat effect needed in a particular crisis, recognizing that within Europe there is no such thing as uncontested operational space likely in a major crisis.

What this means for Germany as they start the process of recovery in terms of Bundeswehr capabilities that new platforms need to be building blocks which pull the force in the right direction, that is shaping an integrated distributed force.

Key allies of Germany and NATO overall are placing a priority on cross-domain operational capabilities within an integrated force able to distribute C2 to operate in a manner which the adversary would find credible.

Building a Relevant Force Structure

I have published a report which has dealt with the German defense challenge and have written extensively on what I have termed the integrated distributed force.

Those reports can be read as background to this article.

But I would summarize the main findings as a baseline by which to address the case study of German’s coming selection of a heavy lift helicopter.

The force we are building will have five key interactives capabilities:

- Enough platforms with allied and US forces in mind to provide significant presence;

- A capability to maximize economy of force with that presence;

- Scalability whereby the presence force can reach back if necessary, at the speed of light and receive combat reinforcements;

- Be able to tap into variable lethality capabilities appropriate to the mission or the threat in order to exercise dominance.

- And to have the situational awareness relevant to proactive crisis management at the point of interest and an ability to link the fluidity of local knowledge to appropriate tactical and strategic decisions.

I would add a specific German requirement as well as they build out what the call along with the French and the Spanish, a future combat air system.

Here the approach is to build a new fighter aircraft by 2040 but do so through the process of creating a more integrated force able to operate by drawing data from a common combat cloud, and to do so by ensuring that integration leads to great force lethality and effectiveness at the distances which European combat forces will need to operate.

And given the twin expansion of the European Union and NATO to which Germany has been a key driver, this means a much larger combat space than the Bundeswehr had to cover in the days of the Cold War.

In the Cold War, direct defense was largely about territorial defense and support of core allies operating from German territory or from other NATO territories in supporting defense of the Central Front.

Now the area German forces need to GO TO is much further than envisaged in the Cold War.

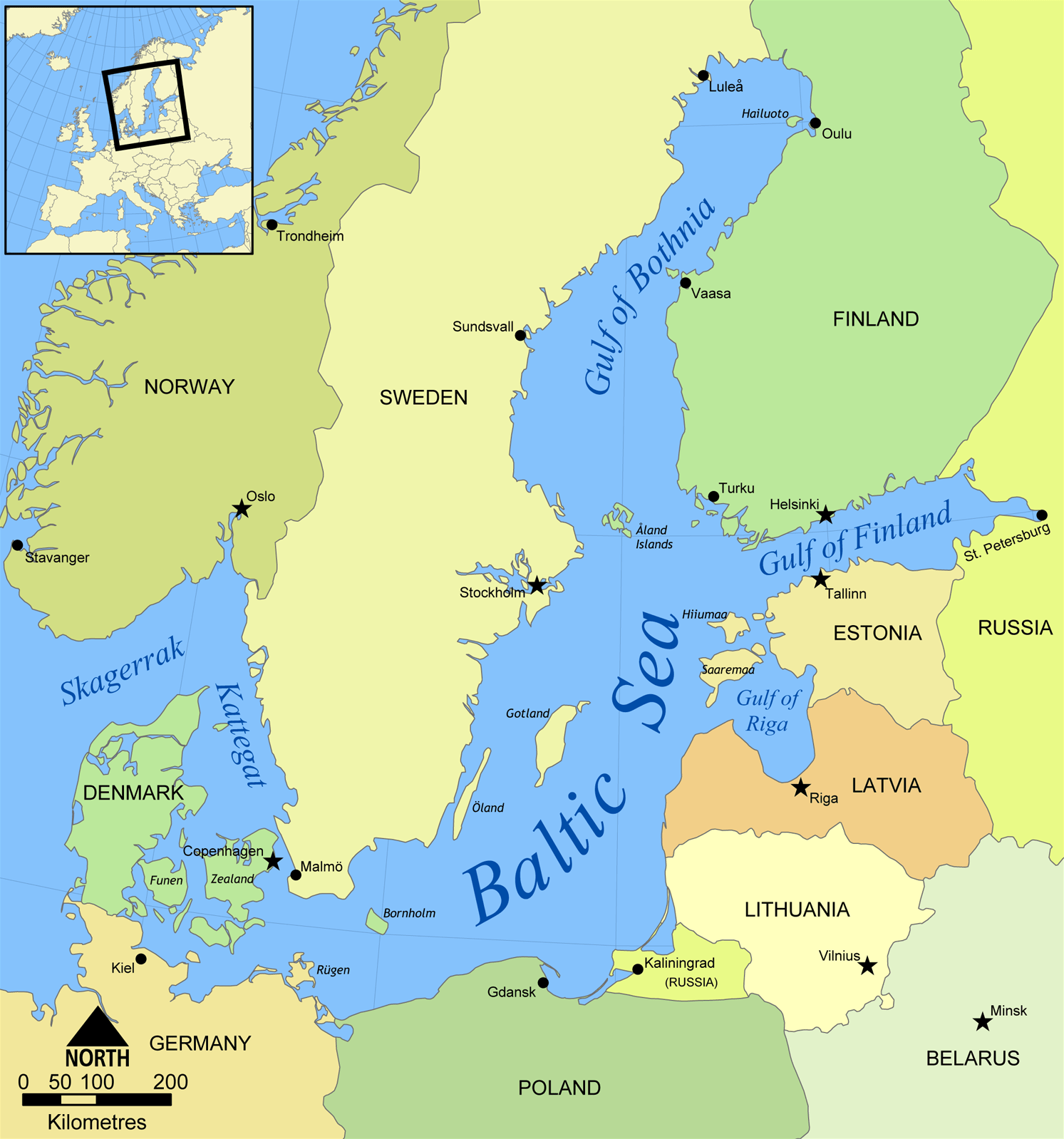

The map at the beginning of the article highlights the dangerous route the Germans need to take to reinforce Poland and the Baltic Republics in times of crisis.

It is not primarily about reinforcing force strength within West Germany; it is about moving force rapidly over distance to the crisis point and making a difference by being interoperable and connected with the relevant allies engaged in dealing with the crisis.

The Key Role of the Heavy Lift Program

The selection of a new heavy lift helicopter is a near term decision for the Bundeswehr which can move it forward towards the force it needs, or can stay within the genre of replacing what it had bought for the Cold War period.

It is a key decision which will either move Germany forward towards the integrated distributed force envisaged in its European focused Future Combat System program or in its most recent NATO commitments to modernize its forces in a way that can support the NATO that has been shaped in the post-Cold War period.

As I argued in my report on German defense published earlier this year:

But key questions facing Germany are very clear.

How will Germany pump money rapidly into the Bundeswehr to repair its severe readiness problems in a short period of time?

Rumsfeld always argued that you have to fight with the army you have, so how will the government take seriously the need to repair an increasingly hollow force?

NATO now has the longest border in its history.

Germany is no longer garrisoning the inner-German border, where are the forces that can project power rapidly to reinforce the Baltic states, the Poles and other NATO allies to the East?

Repairing the Army you have and preparing for serious engagement forward are the two most immediate tasks facing Germany.

During the Cold War Germans spent 4% on defense; where are they now?

Russia directly threatens a core German value – multilateralism.

Putin clearly has a divide and conquer strategy and if Germany is to counter this, then the Bundeswehr needs to be built for force mobility throughout Europe.

This will take significant defense investment delivering capabilities in the midterm; it is not about the long term or an FCAS in 2040.

Preparing for the long-term is important but there needs to be a sense of urgency or there won’t be a long-term or at least one that supports the “European” values one hears so much about in Germany.

To take an example, in the recent Trident Juncture 2018 exercise, Germany committed 8500 of the 50, 000 troops in the exercise, which is a clear declaration of intent.

But to do so, the entire Bundeswehr had to be cannibalized and one clearly could ask how sustainable forward any such German engagement could be in a real conflict?

It is clear the German MoD is looking to its heavy lift helicopter replacement program to set in motion a new approach to how operations and sustainment are to be addressed, clearly in part because the new helicopter is expected to operate over a wider area within Europe than its heavy lift helicopters did in the Cold War.

The approach is built around selecting a single contractor responsible for delivering and sustaining the new build helicopter throughout its operational life. In the past, the sustainment part was done by one company and the build and delivery of the helicopter by another.

But the MoD has understood that in a 21st century platform, this makes less sense as there is a continuous modernization process envisaged in the operational and sustainment process, seen as an integrated whole.

According to the MoD’s Industry Day held in Koblenz, Germany on February 28, 2018, the new approach was articulated and explained to those wishing to compete for the program.

The briefing underscored that the new heavy lift fleet would operate and be sustained from two main operating bases, one at Schönewalde and the second at Laupheim.

These are the two current air bases from which the Luftwaffe operates its rotary wing aircraft. The first is located not far from the “new” European nations of NATO.

It is located South of Berlin and not far from the Polish border.

The Luftwaffe has purchased in common with France, a squadron of C-130Js and is building a new airlift fleet around the A400M European heavy airlifter.

And given the evolution of airlifters, seen in terms of the KC-130J for the Marines in terms of the Harvest Hawk version, and in terms of the projected use of the A400M in the FCAS program of the ability to launch remote carriers, a new heavy lift helicopter should clearly be able to work seamlessly with these other lift assets and to be able to integrate into the evolved concept of what kind of support lift can provide in the future, up to and including working the sensor-shooter relationship across a distributed force.

With the shaping of a new force structure within the context of the current and projected security context for Germany, it makes sense that each new platform or program be made with regard to where Germany is headed in terms of its 21st century strategic situation, and not be limited by the thinking of the inner-German defense period.

How then do the considerations identified in this section affect the heavy lift helicopter choice?

Evaluating the Options

The German approach was laid out in a military aviation strategy paper published by the German Ministry of Defence in early 2016.

The overall approach was defined as launching the Next Generation Weapons System or the Future Combat Air System in which a system of systems approach would be developed with European partners, and provide for the successor to the Tornado and build out the role of unmanned systems or what are now referred to as remote carriers within an overall combat cloud driven system of systems.

The heavy lift helicopter choice will come into being prior to a fully developed FCAS but clearly will be not only affected by the FCAS approach but should be a contributor to the new approach.

This means that it should have connectivity and C2 capabilities which can anticipate the strategic shift envisaged with the FCAS.

Indeed, in the recently held International Fighter Conference 2019, a senior defense industrial official involved with FCAS highlighted the need by 2025 to have significant communications integration between the French and German forces, and that connectivity collaboration was a key element of the FCAS approach.

This would mean as well that the heavy lift helicopter needs to be capable of being part of the connectivity collaboration dynamic as well.

In that same 2016 paper, the German MoD indicated that the MoD had shortlisted the CH-53K from Sikorsky and the CH-47F Chinook from Boeing as the potential successors to its aging fleet of CH-53 heavy-lift helicopters.

According to the paper, the new helo would increase the air mobility of the ground forces as well as contribute to medical evacuation, the support of special forces and to personnel recovery missions.

As of December 2015, the Luftwaffe had 75 CH-53s in its fleet, with some of these being converted to an upgraded version. But the new build helicopter is clearly not just a heavy lift asset but part of a combat assault force necessary to insert German combat capability into the German neighborhood in response to future crises in the neighborhood.

The FCAS commitment provides a framework for rethinking what a support asset can do, as envisaged clearly by what is anticipated by the A400M and its role in launching remote carriers and supporting the networked weaponized force.

It makes sense to consider the heavy lift helo as part of this shift in what is anticipated from the lift fleet as well.

The two options, the Chinook and the CH-53K, provide significantly different options for the Luftwaffe.

The first is provides significant continuity with the past and the legacy requirements; the second provides a significant upscaling of capabilities in line with Germany’s new neighborhood combat engagement requirements and in line with the FCAS strategic trajectory.

There are stark contrasts between the two platforms.

The Chinook is a legacy platform limited in its upgradeability with the older nature of federated systems upgrades; the CH-53K is a key asset in the strategic shift of the USMC to a digital interoperable force similar in many ways to the FCAS approach going forward.

The CH-53 K is built from the ground up as a digital aircraft, and has the kind of C2/ISR infrastructure built in which will allow for the kind of connectivity and combat cloud upgrades envisaged in the FCAS approach.

In other words, the CH-53 K provides an expanded aperture for what support means to a combat force.

The nature of this change associated with the coming of the CH-53K into the integrated combat force was highlighted in a piece which I published earlier this year.

The CH-53K is shaping a new paradigm for heavy lift but it is doing so in the context of a new paradigm of warfare as well, or in the context, of a shift from the land wars to full spectrum crisis management.

Crisis management is evolving significantly. And the Marines as the US’s premier crisis management force is evolving along with the changing demand set.

The Marines are reshaping their force structure to enable it to operate as an effective modular force with scalable force capabilities, which can be tailored to a particular crisis.

The CH-53K is a key part of this modular force.

The aircraft brings new capabilities to the force which are in no way the same as the CH-53E. One of those capabilities is the new cockpit in the aircraft and how digital interoperability and integration with the evolution of the MAGTF more broadly is facilitated by the operation of a 21st century cockpit.

The cockpits are very different and fit in with a general trend for 21st century aircraft of having digital cockpits with combat flexibility management built in. Because the flight crew is operating a digital aircraft, many of the functions which have to be done manually in the E, are done by the aircraft itself.

This allows the cockpit crew to focus on combat management and force insertion tasks. And the systems within the cockpit allow for the crew to play this function.

This means that the CH-53 K and its onboard Marines and cargo can be integrated into a digitally interoperable force. This means as well that the CH-53 K could provide a lead role for the insertion package, or provide for a variety of support roles beyond simply bringing Marines and cargo to the fight. They are bringing information as well which can be distributed to the combat force in the area of interest.

The fly-by-wire system onboard the CH-53K enables the crew to focus on mission management rather than devoting the majority of their attention to simply being able to fly the aircraft and to control the hover process in landing and taking off with the aircraft and its load.

The fly by wire system onboard the aircraft and other digital tools allow for stable flight in a wide variety of operational conditions. And the fly by wire system essentially lands the helicopter on its own – meaning the pilots can focus on the mission at hand or evading a threat, or can safely land in a sandstorm or other degraded conditions.

This approach sounds very convergent with the German MoD’s commitment to shaping a future combat system and a connected, integrated force which can insert combat capability at the tactical edge in Germany’s neighborhood.

In addition, to the core digital capabilities built into an upgradeable-built in to the CH-53K, the aircraft has greater speed and range with much larger payloads than the Chinook.

And this is without even considering the external loadouts which the CH-53 K can carry which are three times the payload weight which the CH-53E can carry currently.

With the USMC completely committed to fielding a logistically sound heavy lift helicopter, they have stood up a logs demo team at New River Marine Corps Air Station in North Carolina which is maturing the sustainment system PRIOR to its IOC. This is a significant difference from when I saw the Marines introduce the Osprey in the 2005-time frame.

This means that even though it is a “new” combat system, it will be thoroughly sustainable aircraft prior to its first combat deployment.

The Marines at 2nd MAW are completing a very successful Log Demo where they have validated and verified the maintenance procedures, maintenance publications and tool requirements and refining them in order to be prepared to main and support his 21st Century aircraft when it reaches the fleet in 2021.

Given the German MoD’s interest in combining operations and sustainment in their operating bases, the Marines will be maturing a system which is capable of meeting this strategic objective for the German procurement.

In addition to having significantly less range than the CH-53K, the Chinook also has two key shortfalls which would be revealed in a combat insertion scenario in Germany’s neighborhood.

The CH-53K is air refuelable; the Chinook is not.

And the CH-53 K’s air refuelable capability is built in for either day or night scenarios.

An additional consideration is that the CH-53K operates standard pallets which means it can move quickly equipment and supply pallets from the A400M or C-130J to the Ch-53K or vice versa.

This is not just a nice to have capability but has a significant impact in terms of time to combat support capability; and it is widely understood that time to the operational area against the kind of threat facing Germany and its allies is a crucial requirement.

With an integrated fleet of C-130Js, A400Ms and CH-53Ks, the task force would have the ability to deploy 100s of miles while aerial refueling the CH-53K from the C-130J.

Upon landing at an austere airfield, cargo on a 463L pallet from a A400M or C-130J can trainload directly into a CH-53K on the same pallet providing for a quick turnaround and allowing the CH-53K to deliver the combat resupply, humanitarian assistance supplies or disaster relief material to smaller land zones dispersed across the operating area.

Similarly, after aerial refueling from a C-130J, the CH-53K using its single, dual and triple external cargo hook capability could transfer three independent external loads to three separate supported units in three separate landing zones in one single sortie without having to return to the airfield or logistical hub.

The external system can be rapidly reconfigured between dual point, single point loads, and triple hook configurations, to internal cargo carrying configuration, or troop lift configuration in order to best support the ground scheme of maneuver.

If the German Baltic brigade needs enhanced capability, it is not a time you want to discover that your lift fleet really cannot count on your heavy lift helicopter showing up as part of an integrated combat team, fully capable of range, speed, payload and integration with the digital force being built out by the German military.

An Additional Insight from the International Fighter Conference, 2019

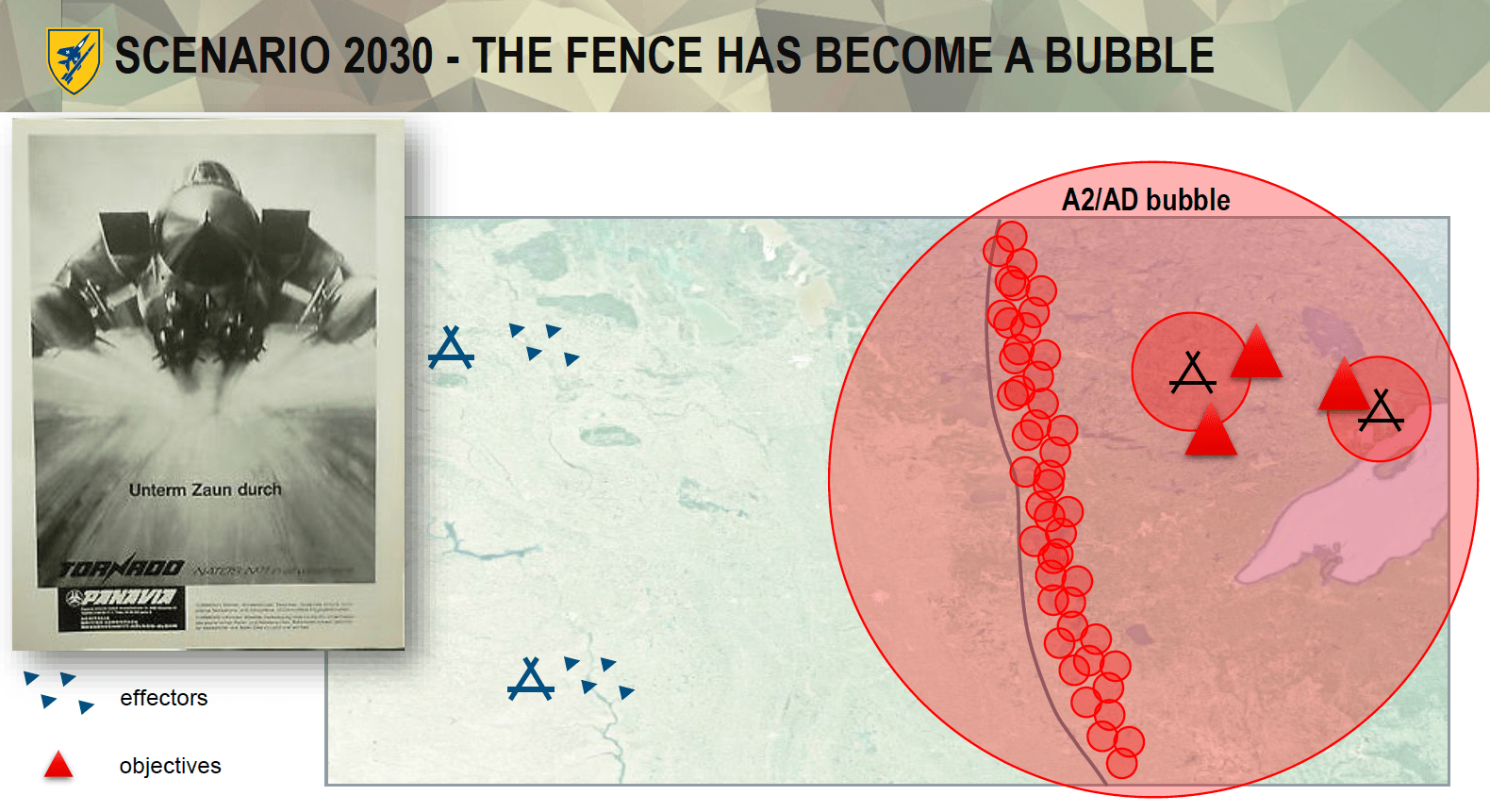

In effect, Germany needs to project power into the Poland-Baltic corridor in times of crisis with Kaliningrad as the flash point or speed bump along the way.

This is a corridor in which mastering the electro magnetic spectrum will be crucial to being able to intervene effectively in a crisis.

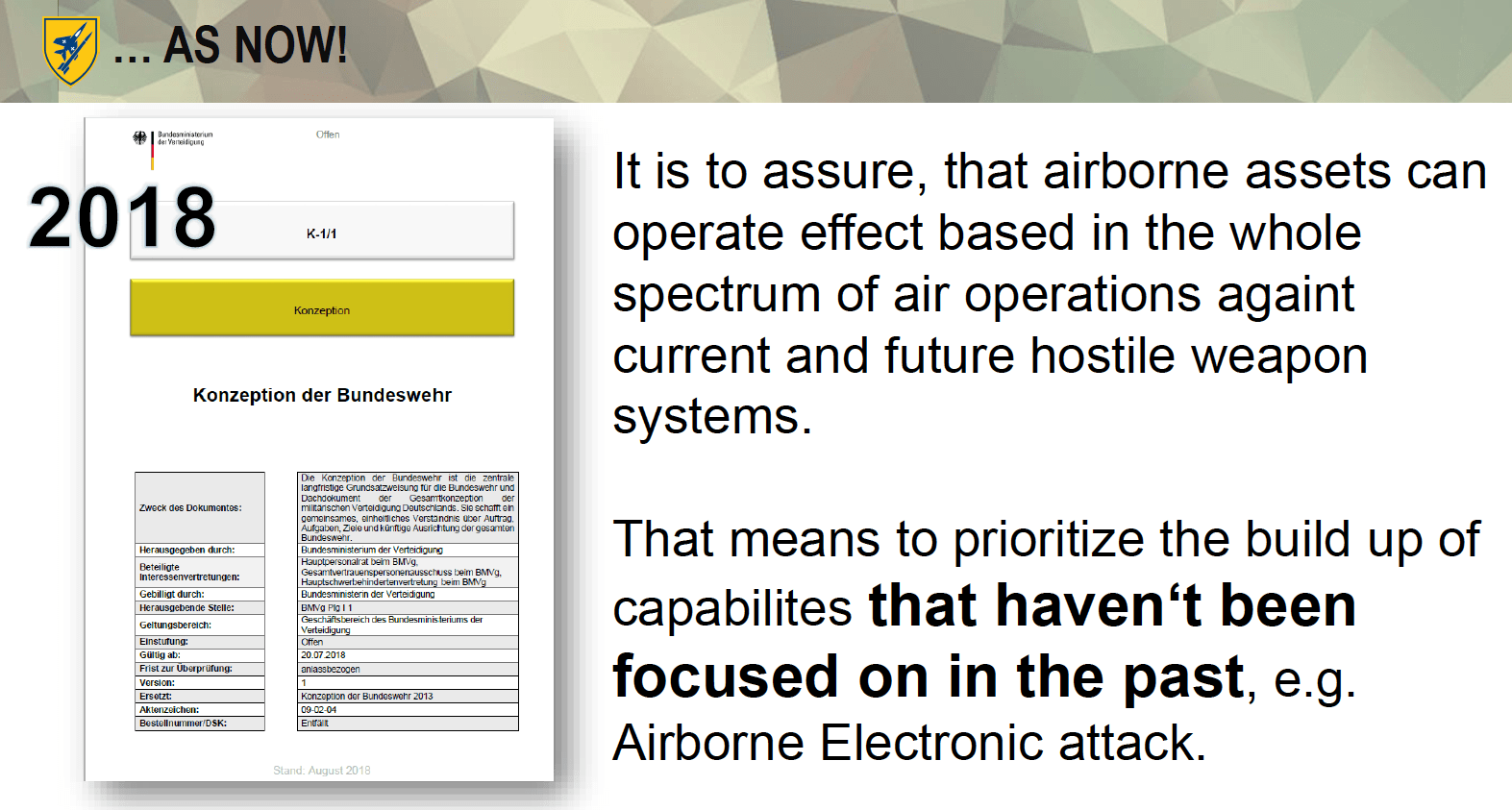

At the recent International Fighter Conference held in Berlin, senior Luftwaffe officers underscored that a major commitment of Germany to NATO in the near to midterm is to deliver new capabilities to fight in the electro-magnetic spectrum. And given the Kaliningrad enclave located along the routes to reinforcement of defense of Poland and the Baltics, such capability is clearly required.

In the presentation by Brigadier General Christian Leitges, the German commitment was highlighted in the slide below:

And obviously, this is not just about attack about an ability to operate a combat force in this environment as well.

The bubble pictured here is Kaliningrad, which from the offensive side is about breaking down the bubble; but from the standpoint of reinforcing the Polish-Baltic corridor, it is about being able to operate in the environment being generated by the A2/AD bubble.

Here the fact that the CH-53K is a marinized helicopter provides a plus in terms of its ability to operate in a different electro-magnetic environment.

In an interview which I conducted in the headquarters of the Deputy Commandant of Aviation in 2016, that aspect was highlighted.

Question: The CH-53 K is a marinized helicopter as well.

While we are at it, could we discuss the differences between an Army helicopter landing on a ship and a marinized helicopter landing on a ship, before the strategic community gets carried away with the notion that the Army can transfer its air assets to ships?

Answer: That is a good point. There are significant differences here.

The first is simply the point about electronic systems; the ship has to turn off many of its systems to allow Army helos to land on ships.

Electromagnetic hardening of the aircraft is crucial so that the electronic components in the aircraft can be protected from radars and other ship-board electronic systems, when it operates aboard naval shipping.

This is especially critical if you are operating a fly-by-wire system.

A recent exercise highlights the challenge if using the Chinook versus the CH-53K to move capability into the corridor.

In the Green Dagger exercise which occurred earlier this year in Germany, the goal was to move a German brigade over a long distance to support an allied engagement.

The Dutch Chinooks were used by the German Army to do the job. But it took them six waves of support to get the job done. Obviously, this is simply too long to get the job done when dealing with an adversary who intends to use time to his advantage. In contrast, if the CH-53K was operating within the German Army, we are talking one or two insertion waves.

And the distributed approach which is inherent in dealing with peer competitors will require distributed basing and an ability to shape airfields in austere locations to provide for distributed strike and reduce the vulnerabilities of operating from a small number of known airbases.

Here the CH-53K becomes combat air’s best friend. In setting up forward operating bases or FOBs, the CH-53K can distribute fuel and ordinance and forward fueling and rearming points for the fighter aircraft operating from the FOBs.

And in the 2016 interview mentioned earlier, the intersection between the unique capabilities of the CH-53K and the support for FOBs was highlighted.

Question: I know that Germany among other allies is considering the K as an addition to their force. And currently, the competition seems to be between the Chinook and the K. How would you compare them?

Answer: It is basically 1960s technology versus 21st century technology with the implications for capabilities, maintainability and flexibility being weighed heavily favor of the K.

The mission is one of lift; and there is no comparison between the two helos.

The max gross weight on the K is 88,000 pounds; the Chinook is 50,000 pounds, they are not even in the same rotorcraft weight classification.

You get to the area of interest faster, safer and with the flexibility of deploying in support of multiple FOBs given the three-hook system.

In short, Germany faces a choice.

It can run in place and add Chinooks to its inventory.

Or it can grasp the future outlined in its Future Combat Air System and in its requirement to engage rapidly in case of crisis in its neighborhood in support of its allies, and introduce the CH-53K and leverage its introduction to move in the new strategic direction which the German MoD has indicated it wishes to go.

It is not just a platform choice; it is a choice for Germany’s defense strategic future.

Clearly, it has been designed, built and sustained as a 21st century combat system for an integrated distributed force.

And it is more survivable, reliable and maintainable than any other heavy life helicopter entering service.

For our archive of CH-53K articles, see the following:

https://defense.info/system-type/rotor-and-tiltrotor-systems/ch-53k/