By Robbin Laird

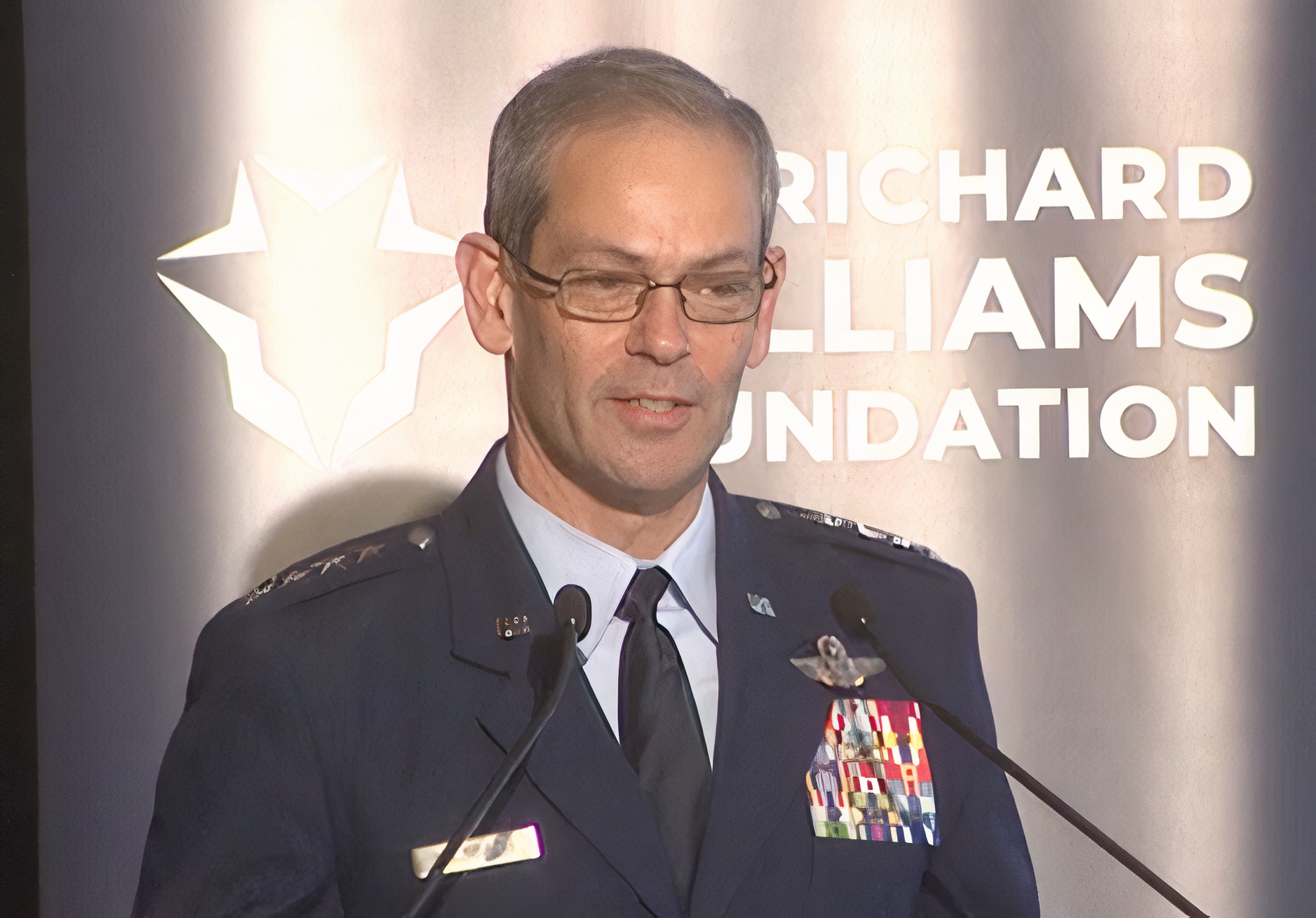

General Kenneth Wilsbach, Commander, Pacific Air Forces, is no stranger to the Williams Foundation.

When the seminars held by the foundation began in 2018 focusing directly on the strategic shift from the land wars to building the resilient and longer range force for deterrence in the 21st century, General Wilsbach, then Commander of the 11th Air Force, provided his assessment of the challenges facing the U.S. and the allies in the Pacific region moving forward.

At that seminar, he highlighted a key element for the way ahead, namely, force distribution of airpower, and he introduced what he would later call agile combat employment.

“From a USAF standpoint, we are organized for efficiency, and in the high intensity conflict that we might find ourselves in, in the Pacific, that efficiency might be actually our Achilles heel, because it requires us to put massive amounts of equipment on a few bases. Those bases, as we most know, are within the weapons engagement zone of potential adversaries.

“So, the United States Air Force, along with the Australian Air Force, has been working on a concept called, Agile Combat Employment, which seeks to disperse the force, and make it difficult for the enemy to know where you are at, when are you going to be there, and how long are you are going to be there.

“We’re at the very preliminary stages of being able to do this but the organization is part of the problem for us, because we are very used to, over the last several decades, of being in very large bases, very large organizations, and we stove pipe the various career fields, and one commander is not in charge of the force that you need to disperse. We’re taking a look at this, of how we might reorganize, to be able to employ this concept in the Pacific, and other places.”

Now as PACAF Commander, Wilsbach has made this a core effort for the command.

When visiting Hawaii this past summer, I had a chance to talk with the PACAF key strategist about how the command was addressing this key way ahead. And this is how BG Winkler, then Director of Strategic Plans, Requirements and Programs at the Pacific Air Force, underscored the effort:

“PACAF has done a pretty decent job over the last three years of getting the Air Force to embrace this idea of agile combat operations and to export it to Europe as well. The whole idea, if you rewind the clock to the mid 80s, early 90s, was that every single base in the United States Air Force that was training for conflict would do an exercise where you’d run around in chemical gear.

“At that point in time, there was a large chemical biological threat, and the Air Force recognized that it needed to be able to survive and operate in that chemical threat. So, we trained to it.

“I think the new version of that chemical biological threat is the anti-access area denial umbrella. The idea of agile combat employment is our capability to survive and operate and keep combat momentum underneath the adversary’s anti-access area denial umbrella.

“Basically, we are focusing on our ability to survive and operate in a contested environment. PACAF has taken a realistic approach that is fiscally informed because it would be very difficult for us to go try to build multiple bases with 10,000-foot runways, and dorms, and ammunition storage all over the Pacific. ”

“What we’ve done instead is concentrated on a hub and spoke mentality, where you build a base cluster. That cluster has got a hub that provides quite a bit of logistic support to these different spoke airfields. The spokes are more expeditionary than most folks in the Air Force are used to.

“The expeditionary airfield is a spoke or a place that we operate from. It’s not 10,000 feet of runway, it’s maybe 7,000 feet. We’re probably not going to have big munitions storage areas, there’s probably going to be weapons carts that have missiles on them inside of sandbags bunkers. And we’re going to look a lot more like a Marine Expeditionary base than your traditional big Air Force base. It’ll be fairly expeditionary.”

What General Wilsbach highlighted in his presentation to the Williams Foundation seminar on March 24, 2022, was the challenge of building the networks to provide for both force distribution and integration.

By shaping a distributed but integrated force, one can create what Wilsbach called the “stacking of effects.”

“Let me explain a little bit about what I mean by stacking of effects, because we found that when going after a highly defended target, it requires that the effects arrive simultaneously from multiple domains to greatly complicate the target’s ability to defend itself.

“A stacked effort might be a space effect happening concurrent with electronic or cyber effects while decoys are being deployed with a submarine prosecuting the attack simultaneously with long range, precision fires that arrive simultaneously on the target.

“To do this at the speed of war, we have to have a network that’s agnostic who detects, engages, assesses or targets takes the shot, whether it’s kinetic or non-kinetic, doesn’t really matter what matters is the speed with which we share information across the platforms and between allies and partners to enable the creation of the overall effect like I just described.”

From my perspective, what the General is describing is reshaping the force from a legacy sequential strike and defense force to becoming a kill web force, able to operate at the point of interest and to be able to reach back to joint or coalition assets to create the desired combat or crisis management effect.

How is the USAF focusing on how to do so?

This is how General Wilsbach put it:

“How do we intend to create such a capability?

“First of all, the U.S. intends to create a more networked force by reinvesting funding from legacy retirements, to into advanced military technologies through continued development of a robust and resilient command and control system and by ensuring joint and coalition interoperability across all domains….

“Additionally, we shouldn’t be flying fit generation platforms with third or fourth generation weapons. I believe we should be investing in directed energy as well as fifth generation munitions and beyond.

“And I’ve not been quiet about my advocacy of the E7, I believe this is essential for us. And as the original customer for the E7, Australia fully understands the long-range surveillance communications and C2 capability E7 provides.

“Adding this additional platform to the U.S. fleet would increase our interoperability with the Royal Australian Air Force and we know the Australian teammates will be able to accelerate our learning curve on the E7….

“Our air force must focus on using information and technologies such as advanced computing and technologies, as well as artificial intelligence, integrating these into future military capabilities. Our next generation air dominance program is applying this methodology to the development of six generation aircraft that will possess the ability to survive, persist, and deliver lethal effects within the most challenging threat environments.”

The command and control piece of all of this is crucial to how one can distribute force, understood as the distribution of a nation’s assets or working with core allies as part of an overall kill web enabled force, and yet integrate those forces to deliver the desired strategic or tactical results.

How to do this is at the heart of shaping a way ahead.

How centralized?

How distributed?

And how best to find ways to empower operations at the tactical edge, yet have effective strategic understanding of what the distributed force is actually delivering?

Much of last year, my colleague Ed Timerplake and I spent considerable time with the 2nd Fleet and Allied Joint Force Command, where Vice Admiral Woody Lewis and his team were standing up a new command capability for the North Atlantic.

At the heart of their efforts was shaping new ways to deliver mission command to a distributed force. They exercised several times throughout his command tour ways to execute mission command through mobile command posts.

That is the Atlantic region, but of course, the Pacific is far vaster, and in one of the great name change mistakes in human history, as my colleague Ed Timperlake has noted, it was called the Pacific.

How then can both mission command and decision making at the tactical edge be done for a distributed but integrated force?

This is how General Wilsbach highlighted how he saw the way ahead in this critical concept of operations and technological domain.

“We’re working as a joint force to develop our C2 concepts and multi domain operations approach. We are continuing the development of a robust and resilient command and control system that can quickly sense, synchronize, decide, and rapidly act with our allies and partners across all domains.

“With the help of Australians on our staff, we’ll continue to address the problem set. The joint, all domain command and control strategy that we are developing known as JADC2 recognizes our need to connect, communicate, and synchronize across all domains, as well as the need to share information at the speed of relevance. In fact, it should probably be called C JADC2 because it needs to extend to our coalition partners as well.

“A vital requirement of JADC2 is the ability to make current and future systems interoperable with systems employed by our joint and coalition partners. And once realized the JADC2 network advantage will be at seamless transfer of the right information at the right time to the right decision maker.

“And at a speed, our adversary cannot match. To realize and operationalize JADC2, the air force is focused on developing advanced battle management system or ABMS. And what ABMS is a system of systems that enables that meshed dynamic flow of data from centralized command and control points to decentralized execution points without being affected by loss of individual networks or nodes, or even a sensor.

“It’ll allow us to collect and process vast amounts of data from all domains and shared in a way that enables faster and better decision making. Imagine commanders at all echelons being able to pull in and synthesize information, and then leverage it in a way that achieves layered effects like it described earlier that shape the battle space faster than an adversary can react to it. That’s true dominance.

“In the Indo-Pacific, an integrated war fighting network is crucial to overcoming the tyranny of distance and the lack of an infrastructure connecting war fighters. In real time, we need a meshed, self-healing artificial intelligence enabled network that is not easily disconnected or vulnerable to attack. It must be user friendly, ensuring operators aren’t distracted by troubleshooting the communication systems when they should be effortlessly executing their work time tasks.

“Much like how your cell phone works, when you go to a new place, it figures out what’s up, you can tell the time you can make a telephone call, check your email, check your social media, and you don’t have to do anything, that’s how this network needs to work.

“PACAF is currently working to deliver this unified network architecture for our upcoming exercise, Valid shield, and teaming with the air staff and industry partners.

“We’re continuously experimenting with machine-to-machine interfaces and connecting military services using multiple network pass. Similar to how SpaceX Starlink terminals are being used to provide redundant internet connections in Ukraine, we intend to test commercial satellite communications as an alternative data transport method during an upcoming Valiant Shield exercise.”

The challenge still remains between empowering decision making at the tactical edge and how strategic direction is shaped.

With the presence forces or the joint task forces at the point of interest able to deploy their own ISR capabilities, their span of effective decision making expands, and with the need for speed they cannot wait for a centralized commander to make a decision not operating in their area of interest.

This is a core challenge which needs to be met, and I mentioned earlier the innovations generated under VADM Lewis are solid beginnings to figure out how to rework mission command in conjunction with decision-making at the tactical edge empowered by the kinds of ISR innovations which are empowering the distributed presence force.

This is how BG Winkler put the challenge when we met at PACAF headquarters in August 2021:

“Our allies and partners are a huge part of everything that we’re going to end up doing out here in the theater. We like to think that they are an asymmetric advantage, and the more that we can get the coalition plugged in the more effective we can be. It’s not just U.S. sensors that are out there feeding the rest of the joint coalition force, but it is important to tap into the allied and partner sensors.

“I do think that we’re at a precipice for information warfare, and the fact that some of the forward based sensors that we have, like the F-35, can generate way more intelligence data than our traditional ISR fleet, like the E3. Australia’s flying the E7—fairly modernized, very robust ISR capabilities on those. I think there’s been some discussion within the United States Air Force about whether we need to up the game and maybe make an E7 purchase, as well.

“But we are getting to that point where the forward base fighters are so much more technologically advanced than our ISR fleet, that it makes you question where the ISR node should be. I agree it doesn’t necessarily need to be all the way back in Hawaii. It could be somewhere else in the theater.

“But the Air Force, as you’re aware, has traditionally operated with AOC as the central node for command and control in the Pacific. We’re trying to figure out as an Air Force what the future looks like. But I don’t think that future is going to be five years from now. I think it might be 10 years from now.

“And in the short term, what you’ll probably see is a something that allows us to operate from the AOC, protect our capabilities to operate from the air operation center, to be able to help synchronize fighters throughout the entire AOR, but then set up subordinate nodes that are probably forward of the AOC. If the AOC does get cut off or shut down, for some reason, you do still have subordinate C2 nodes in the theater that can keep the continuity of operations, and keep some battlefield momentum up, to continue to take the fight to the enemy.”

And PACAF is not waiting around for some future optimal system.

As he underscored about the recent COPE NORTH 22 exercise:

“We also focused on network integration during our recent Cope North 22 dynamic force employment exercise alongside Australia and Japan. Cope North allowed us to build our tactics, techniques and procedures in support of agile combat employment, an operational concept that projects air power via network of distributed operating locations throughout the Indo-Pacific.

“The Australian air force, as well as the Japanese air force were both experimented with ACE, like concepts themselves as many other countries around the world are doing these days.

“During the exercise, we executed 2000 sorties across seven islands and 10 airfields demonstrating operational unpredictability and redundant C2 that enabled rapid employment of fourth and fifth generation air power.”

General Kenneth Wilsbach, Commander, Pacific Air Forces

Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach is the Commander, Pacific Air Forces; Air Component Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command; and Executive Director, Pacific Air Combat Operations Staff, Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, Hawaii. PACAF is responsible for Air Force activities spread over half the globe in a command that supports more than 46,000 Airmen serving principally in Japan, Korea, Hawaii, Alaska and Guam.

Gen. Wilsbach was commissioned in 1985 as a distinguished graduate of the University of Florida’s ROTC program and earned his pilot wings in 1986 as a distinguished graduate from Laughlin Air Force Base, Texas.

He has commanded a fighter squadron, operations group, two wings, two Numbered Air Forces, and held various staff assignments including Director of Operations, Combined Air Operations Center and Director of Operations, U.S. Central Command.

Prior to his current assignment, General Wilsbach was the Deputy Commander, U.S. Forces Korea; Commander, Air Component Command, United Nations Command; Commander, Air Component Command, Combined Forces Command; and Commander, Seventh Air Force, Pacific Air Forces, Osan Air Base, Republic of Korea.

Gen. Wilsbach is a command pilot with more than 5,000 hours in multiple aircraft, primarily in the F-15C, F-16C, MC-12, and F-22A, and has flown 71 combat missions in operations Northern Watch, Southern Watch and Enduring Freedom.

The interview with Winkler along with all the interviews we did with commanders during 2021 can be found in our new book, Defense XXI: Shaping a Way Ahead for the U.S. and its Allies to be published in paperback in June 2022 and available shortly in e-book worldwide.

And we directly focus on the kill web concept in our forthcoming book, A Maritime Kill Web Force in the Making: Deterrence and Warfighting in the XXIst Century.

The featured photo: Royal Australian Air Force F-35A Lightning II aircraft assigned to No. 77 Squadron taxi into position on Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, Jan. 29, 2022. The aircraft flew in to participate in exercise Cope North 22. Fighter aircraft from the U.S. Air Force, Japan Air Self Defense Force and Royal Australian Air Force are projected to conduct aerial refueling, close air support and counter air-missions during the exercise. (U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Micaiah Anthony)