2016-01-02 By Robbin Laird

Although the notion of C5ISR has taken hold, the concept can confuse more than it clarifies.

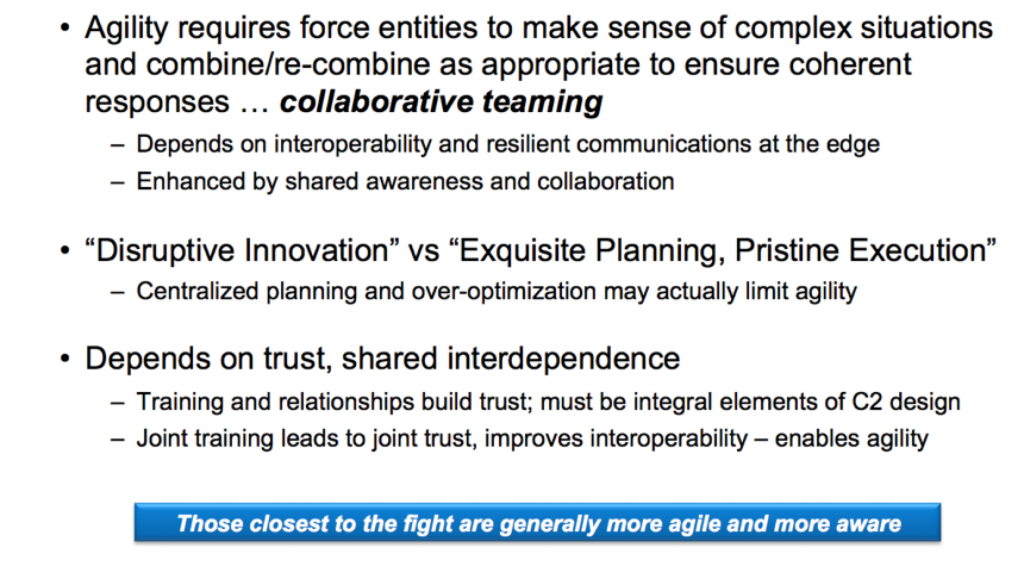

C2 is become an essential element for force structure transformation, rather than focusing excessively on the ISR, or collection of information to inform decisions.

The shift from the kinds of land wars fought in the past decade and a half to operating across the range of military operations to insert force and to prevail in a more rapid tempo conflict than that which characterized counter-insurgency operations carries with it a need to have a very different C2 structure and technologies to support those structures.

The shift to higher tempo operations is being accompanied by platforms which are capable of operating in an extended battlespace and at the edge of the battlespace where hierarchical, detailed control simply does not correlate with the realities of either combat requirements or of technology which is part of a shift to distributed operations.

Distributed operations over an extended battlespace to deal with a range of military operations require distributed C2; not hierarchical detailed micro management.

In effect, the focus is upon shaping the commander’s intent and allowing the combat forces to execute that intent, and to shape evolving missions in the operations, with the higher level commanders working to gain an overview on the operations, rather than micro-management of the operations.

Unfortunately, the relatively slow pace of COIN, and the use of remotes (UAVs or RPAs) in the past decade have led to a growing practice of growing the level of command in order to try to exercise more detailed control. This has led to the current situation in the air operations against ISIS where you have more members of the CAOC than you have actual air strikes!

According to one of the architects of Desert Storm, Lt. General (David) Deptula, the CAOC for Desert Storm was quite lean, and the goal was to get the taskings into the hands of the warfighters to execute, with a later battle damage assessment process then informing decisions on the follow on target list.

It was not about micro managing the combat assets.

And this was with air power multi-mission assets, which went out to execute a command directive in a particular area of the battlespace to deliver a particular type and quantity of ordinance in that area of the battlespace.

With new air technologies, multi-tasking platforms will fly to the fight and execute the initial commander’s intent but will shift to the mission as needs arise during the air combat operation. Fleeting targets are a key reality, which requires an ability for the pilots to prosecute those targets in a timely manner, rather than a deliberate C2 overview manner.

Put in other terms, the command structures will need to “lean out” and to work with warfighting assets where the pilots and operational decision makers are at the point of engagement, not in a building housing a CAOC.

To illustrate the kind of dynamics of change underway, I will use three examples of how forces are being reshaped in a way where new approaches to C2 – organizationally and technologically – are necessary in order to operate in a more fluid, and dynamic battlespace leveraging the new platforms and technologies being shaped for 21st century operations.

Force Insertion: The Case of Osprey Led Long-Range Raids

The Osprey has been a mold-breaking platform in the hands of the Marines as they have used the aircraft over the past 10 years.

Over time, the Marines have found new uses and dynamics of change for execution of missions, and as they have done so have found technological and organizational shortfalls, which need to be remedied with regard to combat approaches.

One such case has been the impact of the Osprey on the speed and range of force insertion.

Unlike a helo, where troops can be loaded up and sent to an operational area in under an hour with their goals and objectives briefed prior to departure and then exit the helo to execute, Marines can be in an Osprey for several hours, and the combat situation can change dramatically during their time to the objective area.

To deal with this, the Marines are shaping information tools to the squads to support decisions to be made when exiting the aircraft, perhaps hours after departure. This is a combination of shaping effective IT means, and the appropriate capability to push decisions to the edge or to the point of attack.

What is different from before is that the squad members need enough accurate information to be confident in how to execute their mission, rather than simply training on what to do when exiting a helo.

At the heart of the approach is working the following challenge:

“We are working to push increased situational awareness, big picture CAOC-type information, down to individual warfighters using secure tablets in tactical aircraft en route to an objective area.”

Based on his experiences in working with the Infantry Officer’s Course and with Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron or MAWTS-1, Col. Orr, when head of VMX-22, discussed the USMC approach to shaping what might be called the combat cloud for the air-ground team.

Col. Orr underscored that for the USMC digital interoperability was about empowering warfighters. He argued that the experience of pilots in having significant connectivity and situational awareness was not the same as what the ground combat element or GCE in the USMC was experiencing.

He described this as a split between the haves and the have-nots.

“In the air combat world, pilots and air controllers have seen significant gains in connectivity and situational awareness. For many of the ground combat element, they were operating in virtually Vietnam era conditions with radio communication as the only link.”

The Marines have been changing dramatically key aspects of how they insert force, notably around the Osprey.

With a rotorcraft, the ground forces and commanders get on the helo and arrive within the hour at the objective area. In an air-refuelable Osprey, the ground forces and commander might spend several hours in the back before reaching the objective area; and obviously, not being informed and able to do mission planning in route is unacceptable.

Whatever gains one might get with speed and range will be lost without enhanced C2 and ISR enabling the GCE in flight to the objective area.

“Our passion right now is taking all of the information from airborne and off-board sensors and pushing that tactical information to a warfighter in the back of the Osprey.

It could be an air mission commander or a ground force assault commander.

We need to provide that sensor-based information to the decision maker so they can make smart and intelligent decisions en route.”

Orr underscored:

“Our effort very akin to the broader USAF combat cloud discussion, only we bring it down to a much smaller taskforce level.

And at that level, we are focused on a specific objective, but it’s one that’s scalable up to a larger environment.

The cacophony of wave forms and proprietary solutions is simply out of sync with where the USMC is going with its new aviation assets and working relationships with the GCE in shaping the 21st century MAGTF.

We’re moving towards a software programmable payload solution that enables a software programmable radio to take sensor inputs in and then put the inputs out in a variety of waveforms.

And this is really where we are headed.”

Currently, the Marines are experimenting with various gateway solutions to empower the GCE working with Marine air to provide for more effective combat solutions.

One item, which has been tested, is the remote control of UAV payloads from ground or airborne situations.

“We’ve executed remote control of payloads from the back of the V-22.

We have also done it from a ground based cyber and electronic warfare coordination center.”

Col. Orr also discussed the USMC effort to merge the complementary capabilities of two traditionally separate, very separate communities.

“We have signals intelligence professionals, primarily ground-based radio battalions who report back up through Title 50 authorities.

And then we have a separate group that does electronic warfare, notably the EA-6B Prowler conducting tactical electronic warfare.

Those two communities traditionally haven’t really talked much.

We are bringing them together in the same facility called the Cyber/Electronic Warfare Coordination Cell (CEWCC).

That Cyber/Electronic Warfare Coordination Cell provides the MAGTF commander the ability to deconflict and conduct operations within the electromagnetic spectrum at a tactical level.

At tactical level, the CEWCC allows us to be able to combine cyber and electronic warfare effects and have the commander make decisions ranging from listening to deception to jamming.”

Finally, he discussed the importance of using tablet-sized software to get information into a usable package for the ground warriors.

“The tablet format allows the user to define what they want to see, not a higher headquarters to decide what you need to see, but to allow the individual operator to pull down that information and scale it to your desired level of detail.”

Col. Orr highlighted the following challenge:

“How do we provide the end user with the right information and provide them the right flexibility to see what they need and what they care about, and do so in the right security framework environment that properly protects the information?”

In future interviews, we will highlight the evolving efforts with regard to digital interoperability and C2.

The Impact of Fifth-Generation Combat Air on C2

The F-22 and even more than the F-22, the F-35, are multi-tasking aircraft not simply multi-mission aircraft which can be directed to the mission.

Put in other words, C2 for fifth generation aircraft is about setting the broader combat tasks and unleashing them to the engagement area, and once there they can evaluate the evolving situation during their engagement time and decide how best to execute the shifting missions within the context of the overall commander’s intent.

Hierarchical command and control of the sort being generated by today’s CAOCs is asymmetrical with the trend of technology associated with fifth generation warfare.

As Robert Evans, a former USAF pilot, and now with Northrop Grumman put the change:

Formations of F-35s can work and share together so that they can “audible” the play. They can work together, sensing all that they can sense, fusing information, and overwhelming whatever defense is presented to them in a way that the legacy command and control simply cannot keep up with, nor should keep up with.

That’s what F-35 brings.

If warfighters were to apply the same C2 approach used for traditional airpower to the F-35 they would really be missing the point of what the F-35 fleet can bring to the future fight.

In the future, they might task the F-35 fleet to operate in the battlespace and affect targets that they believe are important to support the commander’s strategy, but while those advanced fighters are out there, they can collaborate with other forces in the battlespace to support broader objectives.

The F-35 pilot could be given much broader authorities and wields much greater capabilities, so the tasks could be less specific and more broadly defined by mission type orders, based on the commander’s intent. He will have the ability to influence the battlespace not just within his specific package, but working with others in the battlespace against broader objectives.

Collaboration is greatly enhanced, and mutual support is driven to entirely new heights.

The F-35 pilot in the future becomes in some ways, an air battle manager who is really participating in a much more advanced offense, if you will, than did the aircrews of the legacy generation.

Recent discussions at ACC and the recent trilateral exercise highlighted the role which the F-22 is already playing in allowing for the possibilities of a significant shift in C2, although currently constrained by legacy practices, and excessive legalistic control.

In an interview with the Commander of the ACC, General “Hawk” Carlisle, the point was made that the F-22 was a key enabler for the air combat force currently, and had led to a re-norming of airpower in practice.

Carlisle emphasized throughout our meeting the importance of the training transition throughout the fleet, not simply the operation of the F-22 and the coming of the F-35 as in and of themselves activities.

It is about force transformation, not simply the operation of the fifth generation aircraft themselves as cutting edge capabilities.

General Carlisle: “It is important to look at the impact of the F-22 operations on the total force. We do not wish, nor do the allies wish to send aircraft into a contested area, without the presence of the F-22.

It’s not just that the F-22s are so good, it’s that they make every other plane better. They change the dynamic with respect to what the other airplanes are able to do because of what they can do with regard to speed, range, and flexibility.

It’s their stealth quality. It’s their sensor fusion. It’s their deep penetration capability. It is the situational awareness they provide for the entire fleet which raises the level of the entire combat fleet to make everybody better.”

The shift is to a new way of operating.

What is crucial as well is training for the evolving fight, and not just remaining in the mindset or mental furniture of the past.

It is about what needs to be done NOW and training towards the evolving and future fight.

General Carlisle: “The F-22s are not silver bullets.

The F-22s make the Eagles better, and the A-10s better, and the F-16s better. They make the bombers better.

They provide information. They enable the entire fight.

And its information dominance, its sensor fusion capability, it’s a situational awareness that they can provide to the entire package which raises the level of our capabilities in the entire fight.

This is not about some distant future; it is about the current fight.”

And in a follow up interview with the ACC staff, the impact of the F-22 on a very different approach to warfighting and C2 was highlighted as well.

According to an A-10 pilot in the room during the interview, fifth generation really is not about its tactical effect; it is about the operational impact of fifth generation on the entire fleet.

“Prior to the F-22, the individual pilot could only have a tactical effect. Now the pilot can have an operational effect. I can take a much smaller package to have a larger operational effect, which can have strategic impact. Four F-15Cs or 4 A-10s showing up does not have a strategic effect; 4 F-22s can have such an effect.”

A key reason this is true is that the F-22 is the first of the fifth generation multi-tasking aircraft.

What this means that it can change its role during a mission appropriate to the combat task. Or put another way, the F-22 was designed for air superiority but it has redefined the operational meaning of air superiority away from a classic air-to-air role and become an operational impact aircraft enabling the entire air combat force.

The F-22 pilot in the room discussed how the aircraft has been used in the Middle East, and highlighted its flexibility from shifting from dropping weapons, to providing force protection, including dealing with ground based threats to the air combat force, to becoming the air battle manager in contestable airspace. Put in other terms, the F-22 is providing the mission assurance role for the air combat force.

This transformation has simply become part of operational practice; it is the quiet transformation infusing the USAF and the air combat force.

And the recent trilateral exercise in which F-22s flew with RAF Typhoons and French Air Force Rafales highlighted the shifting focus for C2 as well.

General Hawk Carlisle noted that during the exercise “we are focusing on link architecture and communications to pass information, the contributions the different avionics and sensor suites on the three aircraft can contribute to the fight, the ability to switch among missions, notably air-to-air and air-to-ground and how best to support the fight, for it is important to support the planes at the point of attack, not just show up.”

In other words, the dynamic change in how high end aircraft were working together was the crucial point of the exercise. One key difference from the past is the role of the AWACs.

If this exercise was held 12 years ago, not only would the planes have been different but so would the AWACS role. The AWACS would have worked with the fighters to sort out combat space and lanes of operation in a hub spoke manner.

With the F-22 and the coming F-35, horizontal communication among the air combat force is facilitated so that the planes at the point of attack can provide a much more dynamic targeting capability against the adversary with push back to AWACS as important as directed air operations from the AWACS.

As General Hawk Carlisle put it:

“The exercise was a push exercise, namely fifth generation enablement of a high combat force provided by allies. The exercise was not about shaping a lowest common denominator coalition force but one able to fight more effectively at the higher end as a dominant air combat force. The pilots learning to work together to execute evolving capabilities are crucial to mission success in contested air space.”

The impact of fifth generation upon C2 in warfighting in fact leads to the challenge of understanding the difference between tactical and strategic.

In a centralized C2 structure, the leadership makes strategic decisions and develops tactical operations further down the line.

The slow motion war of COIN and remote attacks via robotic systems tends to push the decision makers deeper and deeper into the execution process so that ironically, the higher level leadership becomes significantly less effective in making strategic decisions because they become so involved with tactics that they forget the difference.

As Lt. Col. “Chip” Berke, an experienced 4th and 5th generation pilot and squadron leader has put the difference which fifth generation makes to the decision process”

I also think that although it is a tactical aircraft, it will be part of a strategic transformation.

The ability of the aircraft working with the other elements of the Marine Corps in the future will allow tactical maneuver to have a strategic consequence.

Everyone’s going to have to understand how this aircraft changes the way they do business.

And it’s not going to be as simple as a pilot just having a different sensor or a different capability that comes online with a software upgrade.

This is an entirely new way of not just flying, but flying as it relates to supporting the ground scheme of maneuver, and that’s what we do in the USMC.

In an ironic way, the Marines because they are very comfortable organizationally with pushing decisions down to the combat leader most relevant to the mission are well aligned for the shift which fifth generation warfare enables.

But it is larger than the USMC; it is about redesigning C2 and providing the right kind of technologies for C2; it is not about funding collection agencies for information to enable“strategic” leaders to make “tactical” decisions. It is harder to know whether the culture, and organizational challenge is greater than the technological one.

It is not just about enhanced effectiveness; slow motion decisions will lead to combat deaths, loss of core equipment, and defeat.

C2 for Hybrid War: The Marines Rework the Challenge

In a recent article by Francis Tusa, the age of COIN has been decisively replaced by the demands of what he refers to as hybrid warfare, or his version of what the Marines used to call the Three Block War.

How much more hybrid can you get than the current situation over Syria?

The “traditional” view of hybrid warfare is an enemy who exhibits elements of different parts of the conflict spectrum – some cyber, some conventional, some guerrilla, perhaps.

But look at what US/French (and soon British …?) forces face over Syria today: a low level insurgent threat, which can exhibit some higher level capabilities, and then a very high intensity threat from Russian SAMs and combat aircraft.

Not a hybrid threat from one foe, but one made up of different enemies. That really is hybrid!

Under Marine Corps Commandant Amos, the need to shift from the COIN template as the dominant definer of military engagement was clearly recognized and the shift was started. The first clear statement of this shift was the “return to the sea,” or ramping up combat Marines experience operating from the ampbhious fleet.

As noted in a 2012 article about the shift:

“The Marine Corps is not designed to be a second land army,” he testified, despite its participation in land campaigns from World War I to Iraq and Afghanistan. Instead, he said, the Corps “is designed to project power ashore from the sea.”

“Amphibious capabilities provide the means to conduct littoral maneuver – the ability to maneuver combat-ready forces from the sea to the shore and inland in order to achieve a positional advantage over the enemy.”

The Navy-Marine Corps team “provides the essential elements of access and forcible entry capabilities that are necessary components of a joint campaign,” Amos said.

Fortunately for the Marines, Amos’ passion to restore the naval services’ amphibious capabilities is shared by Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Adm. Jonathan W. Greenert.

The launch of the Bold Alligator series of exercises in 2011 has highlighted the return to the sea, and focusing on enhanced capabilities to operate from the sea base. The maturing of the Osprey and the F-35B arriving on the sea base are powerful enablers for the Navy-Marine Corps team to shape an expeditionary force able to insert force, achieve objectives and withdraw.

Indeed, the Marines are working hard on shape modern and 21st century insertion forces, which can operate across the range of military operations or ROMO. A key part of insuring mission success is appropriate C2 to lead a flexible insertion force into an operation and out of that operation.

In an interview earlier this year, the Commander of the 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade highlighted how important C2 transformation was to the evolving Marine Corps mission set.

In that interview, Major General Simcock highlighted that 2d MEB is shaping – namely a scalable, modular, and CJTF/JTF-capable Command Element, which can provide the leadership and direction for military insertion into fluid and dynamic crisis or contingency situations.

Recently, the Second Marine Air Wing (2nd MAW) held Wing Exercise 15 at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, to train for the kind of C2 flexibility which could support an insertion force in a situation where a near peer competitor was projected to be involved, just the sort of situation which Tusa envisaged. A key part of that exercise was working flexible C2 of the kind necessary for expeditionary forces as opposed the decade behind of relatively static COIN C2.

According to Col. Kenneth Woodward, the exercise director and 2nd MAW operations officer, the exercise drew upon earlier work, as well as scenarios developed in other exercises, notably at 29 Palms, to provide the projected operational context to the exercise.

Continuity with regard to scenarios and linkage back to earlier exercises and preparing the ground for the next ones allows for the kind of dynamic learning process, which is crucial to shaping effective 21st century combat forces.

“What we’re trying to do here at the wing is to ensure that we’re able to provide the MAGTF with support tomorrow, today, as well as we did in the past operations, and build on lessons learned. And continue to focus and train our battle staff to be able to set forth ways to use evolving capabilities as well.”

Col. Woodward emphasized that having an exercise Wing Exercise 15 was very time consuming and challenging so they would do only a couple of such exercises in a year.

“It’s hard at wing level to train ourselves. It’s very difficult because we don’t have higher headquarters right here that could play that role. To do that we have to simulate the different players in the command process to ensure that Wing level C2 is able to meet the evolving challenges in a fluid battlespace.”

What was simulated in the Wing Exercise was the ability to operate in a land environment when a near peer competitor was part of the combat situation. This meant that they had to exercise defensive and offensive actions to support the force, and to ensure operational success.

“We had a near peer competitor, and we had a robust aviation elements and, and surface-to-air defenses to counter their offensive capabilities and in our scenario, we were reacting to some of their attacks.”

Expeditionary logistics are crucial to a dynamic operation which can not rely on pre-existing K-Marts to provide supplies for the operation.

According to Col. Woodward, during the exercise they established a FOB to provide support for the advancing forces. But the question then is how to empower the FOB as part of the dynamic force?

“How do you supply it? Can you do it via truck? Do you get up there via a KC-130? Where’s gas can be stored once you get up there? How are the aircraft are going to get in and out of the FOB?

How do you establish communications at the FOB with our NIPRNet or our SIPRNet?

There are a lot of variables to deal with and to consider.

Our logisticians and our aviation ground support division, were key players in coming up with a plan during the exercise to answer those sorts of questions.”

And the fog of war such as pilots getting sick on mess food and other such intrusions were included in the exercise as well.

Lessons learned in the exercises and real world combat are folded into dynamic learning process so that the Marines can prepare for Hybrid War of the type which Francis Tusa envisages.

Conclusion

And the shock of moving from COIN to hybrid war for some in the military and in the defense analytical community is a profound one.

The slow motion war, or use of remotes for long-range destruction of terrorist or other targets has allowed for the stronghold on operations by a very legalistic process.

The OODA (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) loop has become the OOLDA (Observe, Orient, Legally Review, Decide, and Act) loop and slow action in dealing with fleeting targets means no combat effectiveness,

The OOLDA loop is in direct conflict with the evolving technologies whereby “tactical” decision makers at the point of engagement need to execute and interpret the commander’s intent rather than to be subject to continuous and virtual review of their potential actions.

Combat is fleeting; we are building technologies, which can prevail in the dynamics of rapid action, but without an appropriate C2 system, our technologies will be undercut, and our ability to prevail will be dramatically reduced.

Editor’s Note: The first slideshow highlights the Typhoon in the trilateral exercise and are credited to the USAF.

The second slideshow highlights activity during the Wing Exercise and is credited to the USMC.

In the first photo, 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing Marines initiate and assist with flight requests during Wing Exercise 15 at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct.13, 2015. Performing defensive and offensive measures to counter both traditional and irregular threats based on today’s real world adversaries, the Marines and Sailors learned to work together to accomplish various missions by conducting Tactical Air Command Center operations during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13-16.

In the second picture, Lt. Col. Bradley Philips updates Col. Mark Palmer, the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing chief of staff, on the status of current operations for the aviation combat element during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13, 2015. During the exercise, the Marines participated in various scenarios that tested their ability to use defensive and offensive strategies in order to maximize readiness and efficiency of 2nd MAW. Phillips served as the senior watch officer during the exercise.

In the third picture, 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing Marines assess scenarios with fixed-wing assets during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13, 2015. Performing defensive and offensive measures to counter both traditional and irregular threats based on today’s real world adversaries, the Marines and Sailors learned to work together to accomplish various missions by conducting Tactical Air Command Center operations during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13-16.

In the fourth picture, Lt. Cmdr. Laura Anderson coordinates medical support for the aviation combat element during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13, 2015. Marines assigned to battle staff positions participated in operational planning teams requiring staff input across the entirety of 2nd MAW. Medical planners were a vital link in the exercise as they coordinated a multitude of casualty evacuations and general health and welfare for U.S. Marines and Sailors within the ACE.

In the fifth picture, planners within the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing assess available wing assets in order to support a request made by ground forces during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13, 2015. 2nd MAW aviation assets and its highly trained personnel provide the ground combat element and Marine Air-Ground Task Force commander with unprecedented reach and tactical flexibility. Performing defensive and offensive measures to counter both traditional and irregular threats based on today’s real world adversaries, the Marines and Sailors learned to work together to accomplish various missions by conducting Tactical Air Command Center operations during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 13-16

In the final picture, Lance Cpl. Michael Lobiondo, left, and Lance Cpl. Matthew Cancino patrol a compound during Wing Exercise 15, at Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, North Carolina, Oct. 14, 2015. During the exercise, the security detail patrolled the area to maintain security. While they’re maintaining security, Marines with 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing provide defensive and offensive countermeasures in order to increase the overall readiness of the aviation combat element and supporting units.