SLD sat down with Commander Tina Cutter, Deputy Commander of the National Strike Force and Lieutenant Commander Tedd Hutley, operations manager for the National Strike Force in mid-February of 2010. The National Strike Force is one of the United States Coast Guard elements to be affected by the budget cuts, and the key element being eliminated is the National Strike Force Coordination Center or national command element. This two-parts interview was conducted at the Head Quarters in Elisabeth City, North Carolina: it allows non-Coasties to understand what this command and the NSF does for the nation and how it will be affected by budget cuts.

***

SLD: What is the major mission of the National Strike Force (NSF)?

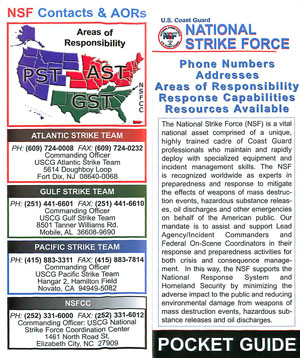

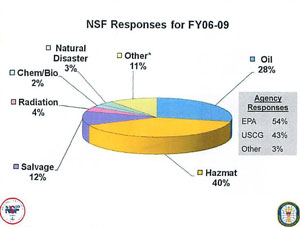

Commander Tina Cutter: The primary mission of the NSF is to support Federal On-Scene Coordinators in their missions to prepare for and respond to oil spills and hazardous materials releases. The national strike force consists of four units:

- the coordination center where we are now,

- and three strike teams located on the Atlantic, Pacific and Gulf coasts.

The teams consist of about 41 active duty billets at each team, and each member of the team from the Yeomen to the 05 commanding officer, is fully trained and deployable. This unit has currently 28 members and we are a coordinating body for the teams; additionally, we perform preparedness and planning missions. We manage national programs, one of which is classification of oil spill response organizations. These are the companies that are hired by regulated facilities and vessels, and are on retainer to be able to respond to certain size spills. The OSRO classification process (Oil Spill Removal Organization Classification) is regulated and determined by certain planning factors.

SLD: Do the regulated and planning factors drive the requirements for the commercial support to this mission site?

Commander Tina Cutter: Correct. We house the data base and we run through all the formulas that tell you how much boom, how much recovery ability, like skimming, you have to have, and how much temporary storage. So we run these companies through this formula and we also do verification, we send inspectors from here in conjunction with the teams out into the field to make sure the companies have what they say that they have.

SLD: So you’re verifying the operational capability to execute on an emergency-basis the mission that they are supposed to have the capability to support?

Commander Tina Cutter: Right, and that’s a very important component of the response ability throughout the country, since these are the first responders for oil spills. It is actually not mandatory that regulated facilities and vessels use a classified OSRO, they could contract with a company that does not have the classification they would just have to list individual pieces of equipment in the plan vice listing the name of the company. It’s a voluntary program that these companies participate in, but it’s the most “mandatory” voluntary program you’ve probably ever seen because the regulated community wants them to have this classification partly because of the inspection program that accompanies the classification.

SLD: Who is the regulated community?

Commander Tina Cutter: The regulated communities are vessels and facilities that handle the loading and offloading of oil. Vessels plans are centrally located at headquarters and facility plans are regionally inspected in the captain port zones for those particular areas.

SLD: So you’re a national Coast Guard command: you execute a public/private partnership, in effect, to working with the commercial sector and then verify their capability to deal with that they themselves might generate from your regulating their self generation clean up capability, is this correct?

Commander Tina Cutter: We operate under the national contingency plan; we are a national special team, available to any federal on scene coordinator, that’s the primary federal official regionally designated to deal with a hazmat incident [hazardous material] or an oil spill. We work for primarily the Coast Guard and the Environment Protection Agency (EPA), but we also have supported the department of defense (DOD), for Military environmental response operations (MERO) and the Department of State (DOS) oversees to provide technical expertise. We also operate under an interagency agreement to support the Navy, if they have a spill or an incident, which was caused by facilities or vessels under their jurisdiction. And we have done that in the past in the Gulf, we sent over, trained personnel to help them respond, the Navy has a significant amount of response equipment available to them through the Navy Supervisor of Salvage.

SLD: So you have a core group of professionals that have specialized equipment to execute the mission: you either have ownership of or access to the MC130’s for air deployability. Do you have any sea assets that you access to, e.g. do you own C130’s ?

Commander Tina Cutter: We do not. A lot depends upon working relationship between the CO (Commanding Officer) of the air station and the commanding officer of the response team, the strike team. In fact, the last several deployments from the Gulf strike team are co-located at the training center down in Mobile Alabama, and they deployed using training flights.

SLD: Could you describe the working relationship with industry in some more detail?

Commander Tina Cutter: Right, the regime in the United States is the polluter pays, and industry is required to have the response capability to respond to the event which they created. The Federal On Scene Coordinator has the legal responsible to ensure that the incident is being addressed. The three main parties that typically are involved in environmental response are the federal government – so, the federal on scene coordinator which is usually the EPA or the Coast Guard, depending on where the incident occurs – and the polluter: the state and the polluter. They work together in a command and control structure to respond to the pollution.

We have the responsibility to make sure that the work is being done, and that’s where our local Coast Guard, the Sector Commander wearing his Federal On Scene Coordinator hat, has the oversight responsibility. And if the federal government steps in and if the polluter is unable or unwilling to respond or reaches the limits of liability, then the federal government is left to address the spill.

Because the NSF is trained on oil spill removal equipment, we are uniquely qualified to supervise response operations. This is critical to ensuring that the necessary work is efficiently and safely performed in the field. At a time when our Sector Commands are stretched to perform all of the safety and security missions they are charged with the ability to call on the expertise of the NSF is very valuable to those communities. NSF members are experts in site safety, response documentation, contractor monitoring.

Additionally, our equipment is like a national insurance policy: a lot of the equipment we would be employing in the case of a catastrophic spill is not available in the commercial sector, for example our equipment that is designed to monitor the effectiveness of chemical dispersants applied to oil spills. We also maintain specialized pumping equipment that is not readily available to industry.

SLD: So from this point of view, the proper way to look at it is as a spectrum of capability. The industry is supposed to have available commercially the ability to clean up spills; you are there to ensure that they do and to have equipment available for when they don’t or more importantly in the case of catastrophic spills.

Commander Tina Cutter: Yes.

SLD: The spectrum is generated by the public-private partnership, which means that if you take away your high end capability you may risk getting essentilly a 80% solution against a situation which requires at least a 98% solution, is that a correct perception?

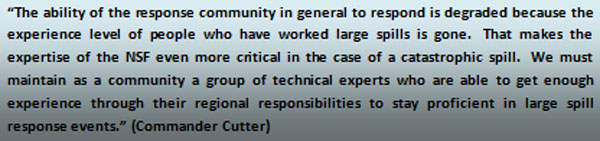

Commander Tina Cutter: I think that, from an equipment standpoint, that is probably a fair statement. Although spills have been declining as a general trend since the implementation of oil pollution control legislation, it is somewhat of a two edged sword in that public tolerance for spills is lessened to a significant degree; also, the ability of the response community in general to respond is degraded because the experience level of people who have worked large spills is gone. That makes the expertise of the NSF even more critical in the case of a catastrophic spill. We must maintain as a community a group of technical experts who are able to get enough experience through their regional responsibilities to stay proficient in large spill response events. We are supporting within the federal government those Sector Commanders who have the ultimate responsibility to manage a coordinated response to keep people safe, even if the Responsible Party is cleaning it up, it’s still the FOSC (Federal On-Scene Coordinator) responsibility. It is an extraordinary amount of responsibility falling on the scene coordinator. So we are augmenting him, we are supporting him in his response or preparedness duties, under the national contingency plan.

———-

***Posted March 30th, 2010