By Pierre Tran

Paris – It is still early days in the studies for a European New Generation Fighter (NGF) and a target weight has yet to be decided, but it is clear 20 tonnes is excessive for the planned fighter jet, a source working on the project said.

Weight is a key design factor in determining the cost and speed of the fighter, the key element in the European Future Combat Air System, backed by France, Germany, and Spain.

The fighter, remote carrier drones and an extensive combat cloud of command and control are the three elements of a Next Generation Weapon System (NGWS) at the heart of FCAS.

There is “constant attention in reducing the weight because of the affordability,” the source said. “The less heavy it is, the less expensive it will be. This is why we believe 20 tonnes is too heavy.

“The philosophy is to make it fast. But we have no clue on where it will land: 18, 17, 15 tonnes…,” the source said. That would be empty weight, without weapons.

The studies show a range of “mission vignettes,” which will set the weight and speed for the fighter.

By way of comparison, the twin-engined F-22 Raptor fighter jet weighs around 20 tonnes, the single-engine F-35 Joint Strike Fighter around 13.5 tonnes, while the twin-engine Rafale some nine-10 tonnes.

Two key French requirements play a large role in the design of the European fighter, namely the fighter will carry a planned fourth-generation, hypersonic nuclear-tipped missile, project name ASN4G, and fly from a planned next generation, nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, which will replace the French navy flagship, Charles de Gaulle.

The partner nations, Germany and Spain, agree the fighter will meet those French specific requirements, the source said.

The then French navy chief of staff, admiral Christophe Prazuck told Oct. 23 2019 the French senate a new fighter jet weighing some 30 tonnes and carrying a heavier payload than the Rafale implied a new aircraft carrier would weigh around 70,000 tonnes and be 280-300 meters long. That compared to the Charles de Gaulle’s 42,000 tonnes and 261 meters.

Seven Pillars of Combat

The new European fighter is the first pillar of seven project pillars, the core element of the Future Combat Air System. The other pillars are a new engine, remote carriers, combat cloud, simulation lab, stealth, and sensors.

Dassault Aviation is the French prime contractor on the fighter, with German-based Airbus Defence and Space as the industrial partner in Germany and Spain.

The planned European fighter will be a twin-engined, stealthy jet, and the stealth requirement calls for an internal weapons bay, which will result in a large overall surface in the design architecture, the source said.

The fighter/FCAS project is entering phase 1B, on a budget of €3 billion ($3.3 billion), with results of the studies to be delivered in 2025. Phase 1B studies seek to decide just what kind of fighter it will be, its capabilities, shape, and size. There is also research and technology to prepare the ground for demonstrating technology in phase 2.

The approach is to simulate and evaluate the various technical factors, working on a virtual “spider web” of elements, and arriving at the “best compromise,” the source said.

Lessons were learnt on the importance of intellectual property rights in industrial negotiations between Airbus DS and Dassault for phase 1B, the source said, and it remains to be seen how IPR will be respected in phase 2. Airbus DS is determined to learn as much as possible on building a fighter jet, seeking to be in the leading position in the coming years.

The plan is to power the fighter with a new compact engine, producing greater power and working at higher temperature, requiring breakthrough in materials and components. The U.S. and France are each working on a range of technologies such as a variable cycle engine, capable of flying at supersonic and subsonic speeds.

“This is very complex to master,” the source said. A technology demonstrator of the fighter is due to fly in 2029, but will not be powered by the new engine.

Safran Aircraft Engines is the prime contractor in the Franco-German aero-engine joint venture dubbed Eumet, and the French company will work on the combustion chamber at the heart of the motor. MTU, its German JV partner, is working on the front section of the motor, and the Spanish partner, ITP, on the back part.

Phase 2, comprising research and technology, and building a fighter demonstrator, is due to start in 2026 and take the fighter project to 2029. The maiden flight in 2029 was delayed a couple of years due to tough talks between Airbus DS and Dassault on the phase 1B contract.

A total budget of some €8 billion has been earmarked for work between now and 2030, including an option for phase 2, the armed forces ministry said Dec. 15.

Phase 3, with development and production of the fighter, is due in the 2030 decade, with delivery of the fighter and related systems in 2040. The total budget for the FCAS program has been estimated at €50 billion-€80 billion, a French senate report said July 15 2020.

Anglo-French Cooperation

An announced industrial cooperation between France and the U.K. on a future anti-ship and future cruise missiles is “much more concrete” than the Paris-Berlin partnership on FCAS and a future main battle tank, said Jean-Paul Palomeros, ex-chief of staff of the French air force and former supreme allied commander of the Nato transformation command in Norfolk, Virginia.

A recent summit between Britain and France was “positive” and pointed up “relaunched cooperation” between the two allies, Palomeros told March 14 the Anglo-American Press Association.

That summit showed London and Paris had renewed ties after an “awful” time after Brexit, he said, and the conversation on their joint missile capability was “concrete.”

That missile cooperation was underscored by the British Storm Shadow and French Scalp cruise missile, and Meteor long-range missile, with the latter a “great success” for European nations, he said.

French president Emmanuel Macron and U.K. prime minister Rishi Sunak held the bilateral summit March 10 at the Elysée Palace presidential office, and their joint statement referred to industrial cooperation on new anti-ship and cruise missiles.

It was “nonsense” that there should be two fighter jet programs in Europe, in view of the vast production cost, said Peter Ricketts, former British ambassador to France and ex-U.K. national security adviser.

“My own feeling is that it is nonsense for Europe to be trying to produce two different fast jet fighters over the next 20 years,” he told March 20 the Anglo-American Press Association. There has been competition for many years between British and French aircraft industry, with the Typhoon and Rafale, he said.

“I don’t think there is room any more,” he said, pointing to the vast cost of U.S. manufacture of the F-35 fighter.

“My feeling is these two programs will come together at some point in the next decade, and there will be one European product with each country taking a share,” he said. But for now, there will be two types of fighters with interoperability, allowing the jets to fly from each other’s airfields, he added.

The summit referred to the scope for cooperation for the future fighters to carry the same weapons, communicate with each other, and be interoperable, he said.

“They commit to concrete steps forward regarding the further advancement of the Future Cruise and Anti-Ship Weapon (FCAS/W) programme to avoid capability gaps. In particular, they commit to deliver a future cruise capability in 2030,” the U.K. and France said in a joint statement on the summit.

That bilateral cooperation would extend beyond missiles to include communications and weapons on the respective FCAS programs pursued separately by Britain and France.

“France and the United Kingdom will seek for commonalities in their respective roadmaps in the missiles domain, notably addressing the needs for the future air platforms. France and the UK will work together on ensuring interoperability of their respective Future Combat Air Systems, including on communication and on armament systems,” the joint statement said.

The joint statement after the summit referred to One MBDA, the joint venture missile maker, whose partners are based in Britain, France and Italy.

The U.K. Goes Global With Japan

The U.K. has added Japan as national partner to its Tempest new fighter jet project with Italy, branding the new industrial alliance, Global Combat Air Programme.

The U.K. and Japan will each fund some 40 percent of development of GCAP, with Italy to finance the remaining 20 percent, Reuters reported March 15, adding that British and Italian defense ministries said respectively they did not recognize those reported remarks and the assessments were speculative.

Besides allied fighters in the GCAP/Tempest project, there are also communications to the U.S. Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter and links to the Australian loyal wingmen drones to be considered, the source said.

Meanwhile, Berlin’s support for FCAS and a Franco-German project for a Main Ground Combat System showed Germany’s willingness for change and ready to “invest in defense,” Palomeros said.

“It looks like they are ready,” he said, pointing out that Germany’s announced €100 billion military budget would accommodate both the FCAS and procurement of the F-35 fighter to allow the German air force to continue its Nato nuclear air component.

“Let’s see,” he said.

Upgrade of Rafale and Nuclear Missile

Meanwhile, the Direction Générale de l’Armement procurement office qualified March 13 the Rafale to F4.1, the first step in the F4 standard, ushering in an “era of collaborative air combat,” the armed forces ministry said in a statement.

The F4 standard, part of the move toward the new generation fighter, will be retrofitted to the Rafale F3-R, plugging the fighter into networks with satellite and software defined radio links for data exchange and communications with other pilots and protection against cyber threats.

The upgrade includes a Scorpion pilot’s helmet with head mounted display for targeting weapons, and upgrades to the active electronically scanned array radar, front sector opto-electronics, and Talios targeting pod.

The fighter will carry new weapons, namely Mica NG air-to-air missile and 1,000 kg armement air-sol modulaire (AASM), a powered smart bomb with GPS and laser guidance. The network upgrade will also allow a Rafale pilot to guide a Meteor missile fired by a fellow pilot to hit the target.

This “incremental development” is intended to meet evolving national and export requirements for the Rafale, the ministry said.

The United Arab Emirates has ordered 80 Rafales at the F4 standard, with first delivery due in 2026 and continuing to 2031. That export deal is worth some €14 billion.

Dassault will work on the F5 version this year, Eric Trappier, executive chairman of the aircraft company, said March 9 at a news conference on the 2022 financial results.

The Rafale carries the supersonic, ramjet-powered, nuclear-armed missile, dubbed air-sol moyen portée améliorée (ASMPA), which is undergoing a midlife upgrade with the ASMPA-R version, and will later be replaced by the hypersonic ASN4G missile.

The DGA said March 22 2022 the procurement office had conducted the second successful test firing of an ASMP-R, which marked certification of the weapon and allowed launch of production by MBDA. The weapon in that test fire was unarmed.

Editor’s Note: on 16 March 2023, the UK Ministry of Defence published their look at their UK-led global combat program:

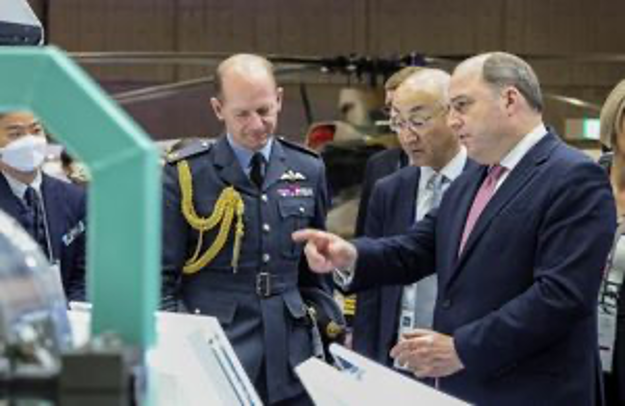

The UK, Japan and Italy joined forces at DSEI Japan to showcase the new Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) publicly for the first time since it was announced late last year.

Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace, has been in Tokyo to view some of the ground-breaking technology that is driving this unique programme and meeting with his Italian and Japanese counterparts.

On display at DSEI Japan was the high-tech GCAP stand, staffed by personnel from the three partnering countries. Attendees were able to see a new 3-metre model of the latest aircraft design and industry partners brought GCAP to life with a cockpit demonstrator and immersive simulators.

Following a joint announcement made by the Prime Ministers of the UK, Italy and Japan in December 2022, GCAP is aiming to deliver a next-generation combat aircraft by 2035. By combining forces the UK and our partners will deliver the military capability we need to overcome fast evolving threats, share costs and ensure the RAF remains interoperable with some of our closest partners.

The project is also expected to drive economic growth and create high-skill jobs. Last year, a report by PWC suggested the UK taking a core role in a combat air system could support an average of 21,000 jobs a year and contribute an estimated £26.2bn to the economy by 2050.

Defence Secretary, Ben Wallace, said:

“The Global Combat Air Programme is an enduring, strategic, partnership that will see the creation of a sixth generation fighter, to protect our skies for decades to come and bring together an alliance of nations, bridging Europe and the Pacific.

“It’s exciting to be working alongside Japan and Italy and see this project fuse the best of all our technologies, locking in a partnership of liberal and open democracies who believe in the rule of law.”

During the conference, industry partners made several collaboration agreements furthering the work of the Global Combat Air programme. They include:

- BAE Systems, MHI and Leonardo continue to work closely together on the next steps in the Global Combat Air Programme with a shared ambition for a joint industrial arrangement.

- Rolls-Royce, IHI and Avio Aero setting out the terms under which they will pool their expertise to design, manufacture and test a full-scale future combat engine demonstrator.

- Mitsubishi Electric (Japan) & Leonardo UK; & Leonardo and Elettronica (Italy) agreeing to form a special domain to develop advanced on-board electronics which will provide aircrew with information advantage and advanced self-protection capabilities.

A new visual identity and logo has also been revealed for the GCAP programme, depicting a future combat aircraft.

During his visit, the Defence Secretary had a trilateral ministerial meeting with Japanese Defence Minister Yasukazu Hamada and Italian Defence Minister Guido Crosetto. The meeting was attended by Sir Mike Wigston, UK Chief of the Air Staff, the two Air Chiefs from Japan and Italy, and industry leadership.

The Defence Secretary also met separately with Japanese Defence Minister Hamada to reaffirm the UK and Japan’s shared values and close defence and security partnership.

They reflected on the importance of our landmark defence treaty, the Reciprocal Access Agreement, signed by the UK and Japanese Prime Ministers in January 2023, and discussed the UK’s recent defence activity with Japan’s Self Defence Forces, including Exercise VIGILANT ISLES and Exercise KEEN SWORD.

The UK Defence Secretary also visited the 1st Airborne Brigade; the unit who hosted British Army personnel for Exercise VIGILANT ISLES in 2022, meeting and observing training by those engaging with our personnel and reiterating the importance the UK places on strengthening the UK and Japan defence relationship.

Featured Photo: UK officials at DESI Japan.