At the September 28, 2022 Williams Foundation Seminar, the Chief of the Australian Navy, VADM Mark Hammond, noted that: “I have spent much of the past 83 days as Chief of Navy working to build strong relationships in Canberra and importantly with my counterparts from Fiji, Indonesia, the UK, France, Japan, India, Singapore, Canada, the United States, South Korea, and Thailand – just to name a few. I have been six countries in the last eight days and am pleased to hold a strong relationship with the French Navy and ADM Vandier, who has generously closed the book to our previous commercial relationship and is focused on our enduring strategic partnership.”

And several stories published by the ADF since August of 2022 have highlighted the working relationship with France.

On 27 August 2022, in an article by Captain Taylor Lynch, the engagement with French soldiers from New Caledonia was highlighted:

Soldiers and officers from the French Armed Forces in New Caledonia (FANC) have arrived at Gallipoli Barracks to begin training with the 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, for Exercise Peronne.

Following their mandatory two weeks of quarantine, the FANC contingent of 28 received a warm welcome from local Indigenous elder Uncle Desmond Sandy, who performed a Welcome to Country ceremony.

Familiarisation training at 6 RAR soon began, so they can integrate with Alpha Company and the rest of Brisbane’s 7th Combat Brigade on Exercise Diamond Dagger.

FANC Contingent Commander Captain Paul said he was eager for his soldiers to learn in an environment completely foreign to them, in a country which has fought side by side with France since World War I.

“The aim is to work together with 6 RAR’s Alpha Company to see how they work, show them our procedures, and work together to improve,” Captain Paul said.

“We are good soldiers, we’re very happy to improve ourselves on Exercise Diamond Dagger.

“The environment is new, none of us have been here before, it’s a new field training area, a new ‘enemy’, but I’m confident we will be able to work well alongside Alpha Company.”

Commanding Officer 6 RAR Lieutenant Colonel Richard Niessl said the FANC contingent were eager to take advantage of their time in the Australian bush.

“They’re young, they’re energetic, they’re motivated, they’re keen to be here, they’ve got the same level of enthusiasm for being in Australia as we would have if we had the opportunity to go to France or New Caledonia,” LTCOL Niessl said.

“This week they’ll do their integration with Alpha Company, including training on the vehicles, weapons training, some physical training sessions, so we can commence Exercise Diamond Dagger next week.

“We’ll do the field-based integration over the next few weeks.”

LTCOL Niessl said combined training with the FANC was important.

“The most important thing is that we strengthen our relationship with the French Armed Forces, we build stronger connections, develop our interoperability, and learn from each other,” he said.

“Strengthening the connection between our two nations is vital, so when we do need to work together in the future, the foundations are already in place.

“The FANC contingent have been excellent, they fit in perfectly, and they’re very eager to learn.”

On 23 August 2022, an article focusing on cooperation with the French air and space force was published:

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and the French Air and Space Force (FASF) rendezvoused over the Coral Sea on 17 August 2022.

Following the FASF’s deployment from France to New Caledonia, travelling over 16,000kms, Dassault Rafale fighters and a Multi-Role Tanker Transport aircraft were greeted by RAAF No. 6 Squadron EA-18G Growlers between New Caledonia and Australia.

Commander Air Combat Group, Air Commodore Tim Alsop, said the meeting highlights the strength of the continued engagement between the two nations, and the ability to deploy air combat capability at short-notice.

“The FASF conducted a rapid 36 hour deployment to New Caledonia with Dassault Rafale aircraft and a Multi-Role Tanker Transport,” Air Commodore Alsop said.

“The capability to rapidly deploy with a small but potent force demonstrates the RAAF’s ability to project power and respond efficiently at short notice.

“It was a fantastic opportunity for our Growler aircraft to join the French Dassault Rafale aircraft for the last leg of their journey to Australia.”

Australia and France’s continued defence relationship is driven by shared values and an ongoing commitment to regional stability within the Indo-Pacific region.

Air Commodore Tim Alsop said both nations are committed to further enhancing engagement and interoperability.

“We are committed to ensuring a stable, open and inclusive Indo-Pacific region, and will continue to work closely with our coalition partners.”

French and Australian forces have come together again during Exercise Pitch Black 22 in the Northern Territory which will run until September 8.

And finally in the RAAF’s official newspaper published on 27 October 2022, the cooperation on air tankers was highlighted during Exercise Pitch Black 2022.

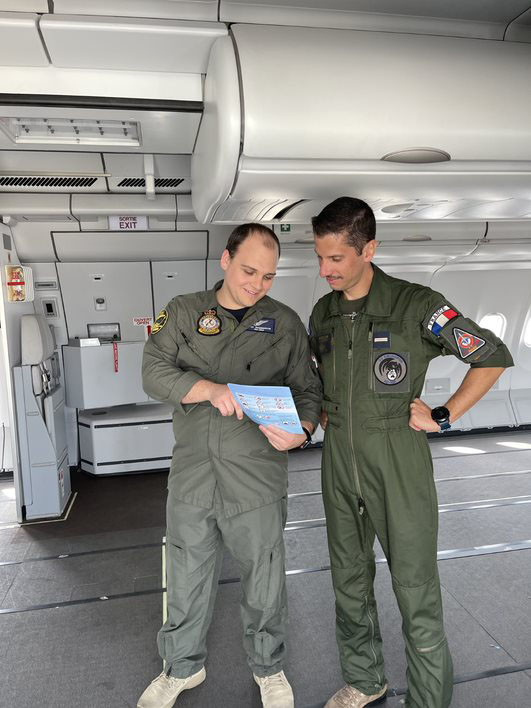

FLTLT Rob Hodgson 33SQN recently had the privilege of hosting a French Air Force Airbus Multi-Role Tanker Transport (MRTT), and personnel from both countries took the opportunity to strengthen mutual ties and professional development through collective training.

The French aircraft was based out of RAAF Base Amberley as part of a commitment to Exercise Pitch Black 22.

Both services are equipped with the Airbus A330 MRTT, known as the KC-30A in Australian Service and as the Phenix in French Service.

The French deployment coincided with 33SQN conducting cabin manager ground training as part of an upgrade program. All cabin managers must complete the training prior to commencing flying training.

Crew Attendant with 33SQN CPL Ryan Massingham helped facilitate the collaboration with the French Air Crews.

“The cabin manager training involved multiple scenarios, implementing a wide variety of emergency procedures such as preparing for an emergency landing or reacting to an on-board galley fire,” CPL Massingham said.

The timeliness of the visit pro- vided the opportunity to involve the French Air Force cabin crew members in the training.”

The French crew members observed how ground training evolutions and scenarios were conducted. They also provided feedback to 33SQN crew attendant instructors on how the French complete their scenarios and procedures.

“The French Air Force crews operated to a high level of professionalism and we both gained a lot through our interactions during their stay,” CPL Massingham said.

“They were also very inviting to our crew attendants, allowing us to observe how they conducted business.

“This wasn’t limited to just ground based activities as we had a mutual inter-fly agreement, so we were able to learn from each other in an airborne environment.”

As the launch operator of the air- craft type, the RAAF has built up an enviable level of expertise in the operation of the Airbus A330 MRTT.

The success of the aircraft in operational use has since led to its acquisition by a number of other nations including France, the United Kingdom, Singapore and South Korea.

And, most recently, in a 7 November 2022, a story by Sgt. Matthew Bickerton, focused on army training for the two forces:

Leeches, snakes, and a ‘velociraptor-like’ bird greeted soldiers from the French Armed Forces in New Caledonia in Tully, while training with the Australians from October 17-28.

They also encountered giant white-tailed rats, big lizards, beetles, swarms of ants and a cassowary – a large bird known for attacking humans with its dagger-like claws.

Private Thimeo, a squad leader from the 3rd Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment, said the cassowary was such a curiosity, but they were told to stay away from them.

During training soldiers discovered all sorts of critters that bit, stung and sucked.

“We had leeches all over our ankles, wrists, neck and tummy,” he said.

“We pulled them off using a lighter, salt, and the issued insect repellent, which is what the Australian soldiers recommended.”

The French soldiers trained with the 8th/9th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment, taking part in camp searches, attacks, jungle living, ambushing and counter ambushing.

Private Thimeo said for most of the French soldiers, it was their first-time combat training in the jungle.

“The difference here is that it gets super-hot, then in an instant it just rains,” he said.

“We’re forced to adapt how we fight and communicate in the field.”

The training ended in a resilience exercise called True Grit.

This involved a bear pit, stretcher carry, bayonet assault course, blindfolded weapon assemblage, a memory game, and an obstacle course.

Traversing ropes upside down on the obstacle course was challenging, Private Thimeo said, but found the bear pit to be a welcome cool down during the physically demanding activity.

Sections competed for the fastest time, with the French coming out on top.

Featured Photo: Corporal Ryan Massingham, a KC-30A Crew Attendant with No 33 Squadron, conducts Cabin Manager Training with a French officer of the French Armee de L’air at RAAF Base Amberley on 8th September 2022. The Armee de L’air stationed an Airbus Multi-Role tanker transport at RAAF Base Amberley in Queensland, during Exercise Pitch Black 2022. Credit: Australian Department of Defence.