By Robbin Laird

The launch point for the Williams Foundation Seminar held on September 28, 2022 was the presentation of Dr. Alan Dupont.

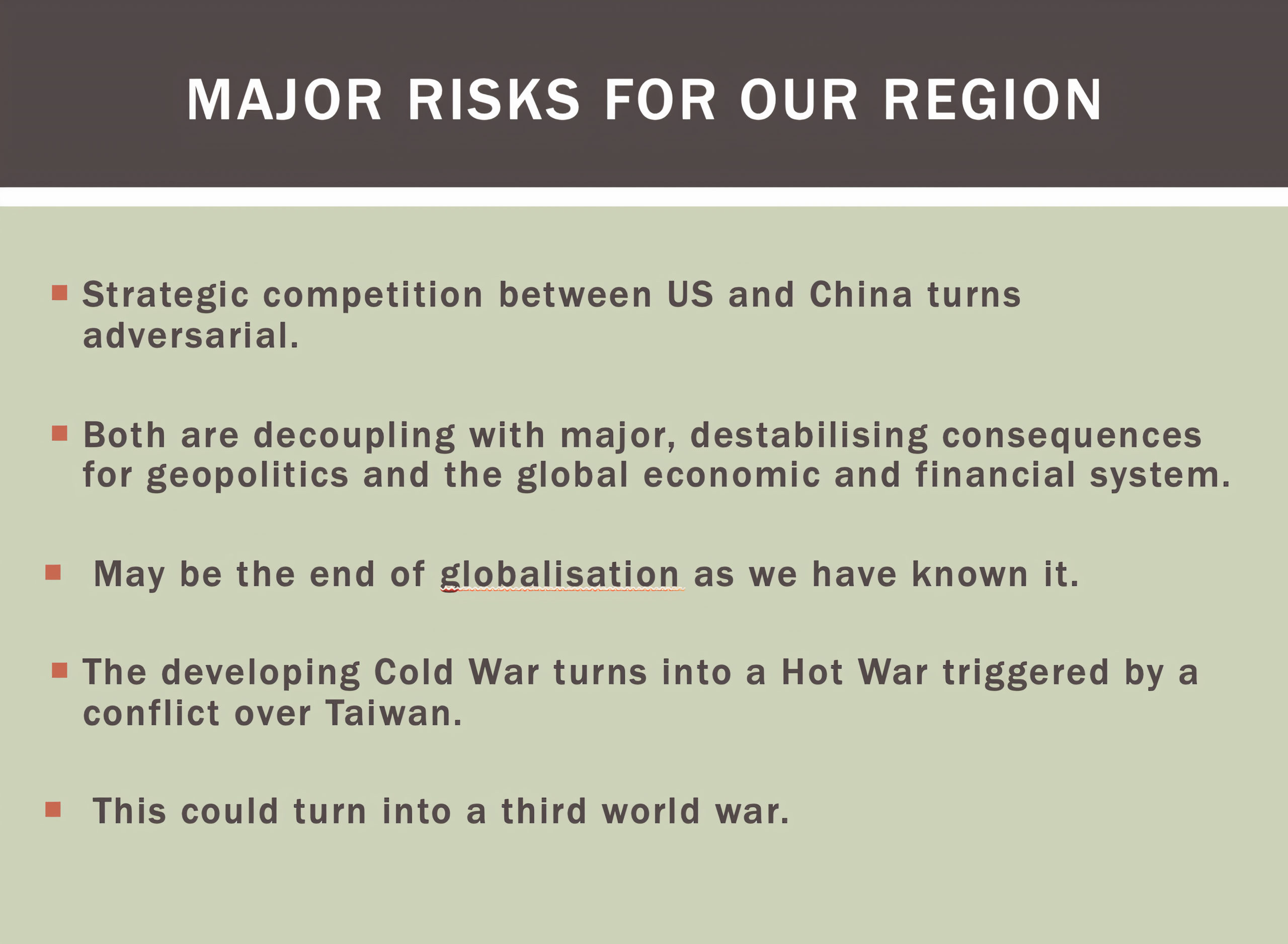

Dupont provided a comprehensive examination of how fluid and dynamic that environment was for Australia and the liberal democracies. He underscored that several crises were happening at the same time, and that the demand side on nations of having to deal with multiple crises at the same time presented an overload situation.

For Australia, this meant that its economy was challenged by several developments at the same time. The pandemic exposed the supply chain vulnerabilities of an island continent. The globalization disruption and re-direction meant that the core relationship between China and Australia which has been part of Australia’s prosperity was significantly undercut. The war in Ukraine posed both supply chain disruptions, economic downturns and brought back dramatically the threat of global conflict.

For the nation, Dupont underscored that defence and security were clearly not simply an ADF challenge or to be funded simply by defence budgetary requirements. How to build more secure supply chains? How would doing so disrupt the trade order and the global WTO rules? How to deal with the energy crisis? How to ensure energy supply? How will Australia deal with coal and nuclear energy issues?

The broader point was simply that defence was no longer the province of the professional ADF; the global crises posed challenges beyond the remit of a professional force like the ADF could deal with.

And what is required was shifting from a peacetime mindset to one which understood the cascading challenges to Australian sovereignty and to the nation.

The Chinese challenge to the region is broad based. It is military, it is commercial, it is political, and it is about comprehensive security challenges, such as cyber intrusion and actions like its security pact with the Solomon Islands. Just deal with this challenge alone provided the need for a comprehensive rethink concerning how Australia dealt with its security and defence challenges.

This requires a geographic shift for the ADF.

This is how Dupont put it on a piece published in The Australian shortly after the seminar:

“Our posture is far from ideal. There is an imbalance between where our forces are and where they need to be. Most of the ADF is comfortably located in our major southern cities, along with their equipment and supporting infrastructure and enablers. But the main threats are to our north. Northern Australia is poorly defended and doesn’t have sufficient capacity to support enhanced ADF and allied deployments into the western Pacific, the most likely conflict arena.

“None of the navy’s major fleet units are based in the north. People’s Liberation Army intelligence collection and war-fighting ships patrolling the Timor, Arafura and Coral seas know our frigates and destroyers will take days to reach them from their bases in Perth and Sydney. The only significant naval ships in Darwin are patrol boats, which are used primarily for constabulary tasks. There is no air-defence system in northern Australia able to protect vital oil, gas and military installations from missile attack.”

In other words, the more specific military challenges require Australia to focus on how to use its geography to its and to allied advantage. This means finding ways to work in Western to Northern Australia to Australia’s first island chain. Dupont both in his presentation and in the interview he had with John Blackburn and me a few days after the seminar, highlighted the importance of leveraging the Northern Territory.

But to do so he argued that innovative new ways to raise capital for infrastructure development was required. Notably, he highlighted the importance of public and private partnerships to do so.

Dupon also underscored that shaping new defense and security infrastructure and training facilities was an important opportunity to involve core allies of Australia, notably the United States, Japan and South Korea, in involvement in building out the defense infrastructure in the Australian continent and find ways to shape more effective integrated training at the same time.

It should be noted that building 21st century basing involves force mobility, so the question of how one builds defense infrastructure in this area involves as well significant innovation regarding basing mobility and shaping both Australian and allied capabilities for what has come to be called agile combat employment. Former PACAF chief Hawk Carlisle referred to this dynamic as “places not bases.”

During the day, other presenters weighed in with regard to how the evolving environment changed the defence dynamic. For many of the speakers, the focus on defence from the continent to the first island chain required a major focus on how to reset the force for this primary mission set. This meant force mobility and working tradeoffs between enhanced hardening of bases and base mobility.

With regard to base protection, what would be the role of active and passive defense? How might the Air Force and Army work more closely to deliver more survivable distributed force basing? What kind of mobile basing was feasible? What role for seabasing in relationship to the force mobility dynamic? What role might civilian assets, such as merchant marine assets might play in such an effort?

Longer range strike has been identified a key element of the building out of Australian defence capabilities. In 2018, the Williams Foundation held a seminar which directly dealt with the need for shaping longer range strike for the force. Air Marshal (Retired) Brown had summarized a key aspect of that seminar as follows: “I think we need a serious look within our focus on shaping industry that both meets Australia’s needs as well as those of key allies in the missile or strike areas.

“We build ammunition and general-purpose bombs in Australia, but we have never taken that forward into a 21st century approach to missiles and related systems. We should rethink this aspect of our approach. There are plenty examples of success in arms exports; there is no reason we cannot do so in the weapons area, for example.”

Since that time, the Australian government has committed itself to do so, but given the threat envelope and the affordability challenges, how best to build out long range strike for the ADF? How to manage targeting tradeoffs? At what range does the ADF need to be able to strike an adversary? How does the ADF manage risks in the targeting areas in terms of getting a crisis management impact without leaving the Australian strike inventory at perilously low levels?

How does Australia build a capability with allies in which a range of strike weapons could be built, stockpiled and used in a crisis? How to get a more affordable inventory of weapons?

It was not mentioned in the seminar, but the coming of directed energy weapons to capital ships could have a significant impact on the deployed distributed force and deliver enhanced integrated lethality and survivability at the same time. For example, the new Hunter class frigates could deliver such a capability if so configured.

And longer range strike is not simply kinetic. What role can cyber offensive operations play in disrupting Chinese military operaitons, supply chains and Chinese domestic control and manufacturing capabilities?

In other words, the evolving strategic environment and the impact of multiple crises is setting in motion in Australia the biggest change in defence seen in recent years.

And in dealing with this challenge, the ADF re-set will not be defined by the acquisition of big new weapons programs, but by taking the current force, re-setting it, re-deploying it and building out from this effort to force design modernization defined by the gaps identified and the needs which can be met within the short-to-midterm rather than envisaging a force in 2030 or 2040 in abstract war-gaming terms.

And if it is only left to the ADF and what the defence budget can fund, the defence and security re-set will fall far short.

The featured graphic is a slide from the presentation to the seminar by Dr. Dupont.

See also the following: