By Robbin Laird

On February 27, 2022, the German Chancellor announced a major re-set of German defense and security policy.

On that date, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz pledged a €100 billion increase for defense procurement spending.

This commitment was certainly welcomed by Germany’s allies, but the challenge of turning enhanced investment into relevant defense capability is a challenging one, and certainly not just for Germany.

When West Germany crafted a strong defense capability in the 1970s and 1980s, it was built around territorial defense and being able to prevail in the war that might come through the inner-German border. The German Bundeswehr was built around conscription and tightly integrated with allied ground and air forces deployed on German soil.

This template is not relevant to what Germany and NATO need to do in the new circumstances. Clearly, German investment in credible defense of German territory is clearly needed, not the least of which being that Germany is hosting the major NATO logistics base in Central Europe.

But as new NATO nations join — Finland and Sweden — and focus shifts to forward defense of the areas most under threat of direct Russian assault, combing both World War II tactics with more modern innovations — Germany needs to sort through what it needs to shape in terms of power projection to the perimeter of Germany itself, including enhanced engagement with the Baltic region, meaning, Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and the Baltic states.

This requires capabilities to move relevant assets to the key choke points which might appear in case of Russian aggression. And choke points in the evolving conflict situation in Europe requires both non-lethal and lethal means of engagement.

The Germans will be working the re-design and re-direction of their forces as their allies do as well.

What templates for the development of German military capabilities will make the most sense?

How can innovation be enhanced to allow for cross-national capability development?

In my co-authored book on the return of direct defense in Europe published prior to the Russo-Ukrainian war, we highlighted how we saw the German situation and its potential role in shaping a more effective European defense capability.

“The Nordics are the most active coalition partners of Germany, and they are focused significantly on direct defense as a core issue and seeing a combination of defense modernization and social mobilization as necessary to deal with the new Russia. What will be the common German and Nordic convergences in meeting the direct defense challenge?

“There clearly are some in play, such as the purchase of common submarines for Norway built in Germany with the Germans committing to the same buy as well….

“What exactly constitutes direct defense of Germany that is focused on Poland, Central Europe, and Ukraine? What mix of forces would be most useful here? Again, this not a question of simply increasing defense spending; it is a question of spending it on what capabilities and with whom to work to provide for enhanced direct defense.”

Or I could put it another way: What do the NATO allies in the perimeter of German defense expect Germany to be able to do for a more credible forward defense of the region?

This means specifically, the Nordics and notably with the addition of Finland and Sweden this means how to turn the Baltic Sea into a NATO-lake?

It also means coming to terms with Poland, a state at odds on “European values” with Germany.

It also means projecting power to the front-line Baltic states as well as to Romania.

And given the presence of Kaliningrad as a threat within Europe itself, Germany has to be prepared with its closest neighbors to destroy Russian military forces in Kaliningrad as part of any escalating crisis management scenario.

In other words, simply sketching the new context means that unlike the Cold War where West Germany built its defense to provide a bulwark for shock absorbing a direct hit, Germany now most find ways to credibly defend against direct strikes by Russian air and missile forces as well as project power to the defense perimeter at distance.

Put in other words, reversing the decline in defense spending is not enough.

There is a need for a clear defense policy and strategy which shapes tools which Germany needs to work not only to defend its territory against air and missile attacks but also which allow it to work effectively to work with its partners on the perimeter of Germany to shape integrated defense capabilities.

Clearly, Germany faces many challenges to be able to do so, but I think it is crucial to highlight the target goals to reach in terms of real force and crisis management capabilities which dovetail with core allies whose territory would most likely be where the battle would be generated by Russian actions.

In other words, credible defense resets on the capability of Germany and core European allies to deploy forces and work closely together in a crisis. It is not about simply hosting U.S. forces, which are increasingly stretched and going through their own very challenging transition from the land wars.

Working Forward Defense

In 1985, when I set up a working group at the Institute for Defense Analysis on Germany with a focus on possible unification, one of the participants in this effort was my friend the late Ronald Asmus. Throughout his life, we frequently discussed Germany and European defense, then interpreted by the Clinton Administration of which he was part as shaping a w ay ahead for NATO expansion.

But his key point was when the capital of Germany would shift from Bonn to Berlin, inevitably Germany would shift its focus from its inclusion as a state in the West, to becoming a part once again of Central Europe and the future evolution of the region.

This certainly has happened with regard to the European Union and Germany’s leading role in the European Union; but it has not happened really with regard to defense.

Because if it had, then Germany would have built a resilient defense structure within Germany to support their ability along with allies to project power forward into the Central European and Baltic regions.

And with allowing their defense capabilities to atrophy, any rebuild needs now to return to the focus which German unification opened up but saw little or real commitment to shaping a defense capability to marry with its broader foreign and economic policies in Central Europe.

What essentially does this entail?

It starts with shaping a more resilient Germany from a security and defense point of view.

This means energy resilience, an ability to supply energy for forward deployed Alliance and German forces; this means resilient defense of logistic supplies and ability to move those supplies forward; NATO has already identified this as a key role for Germany.

To do this will require enhancing air and missile defense, something the Chancellor has already highlighted. Clearly, adding the F-35 to the Luftwaffe provides an important stimulus; but also working more closely with the Poles who have really prioritized active defense, including being the only NATO ally to adopt an integrated approach being offered through the IBCS system.

With effective air and missile defense, the challenge then is to move forward the kind of combined arms packages required for specific areas of operations.

I would argue that indeed we will and are seeing innovation in this area of combined arms packages. This involves innovation with regard to what kind of assault forces, combined with what kind of ground maneuver defense forces and what kind of integrated kill web strike capabilities can be leveraged across the national and allied forces. And then how effectively to deploy such forces to a specific defense or combat area.

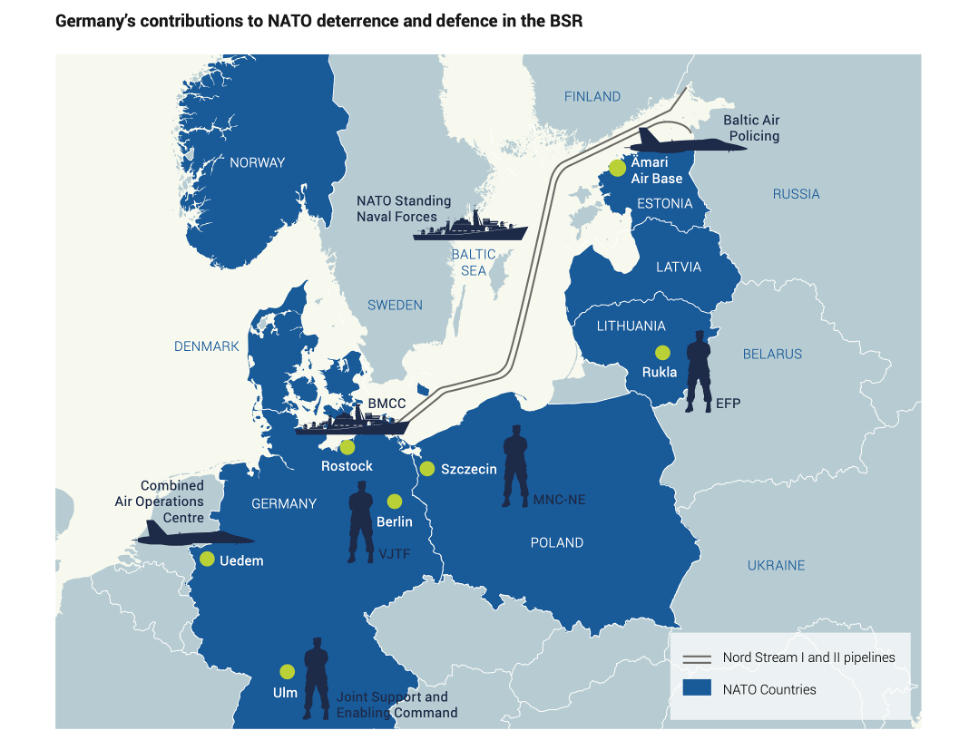

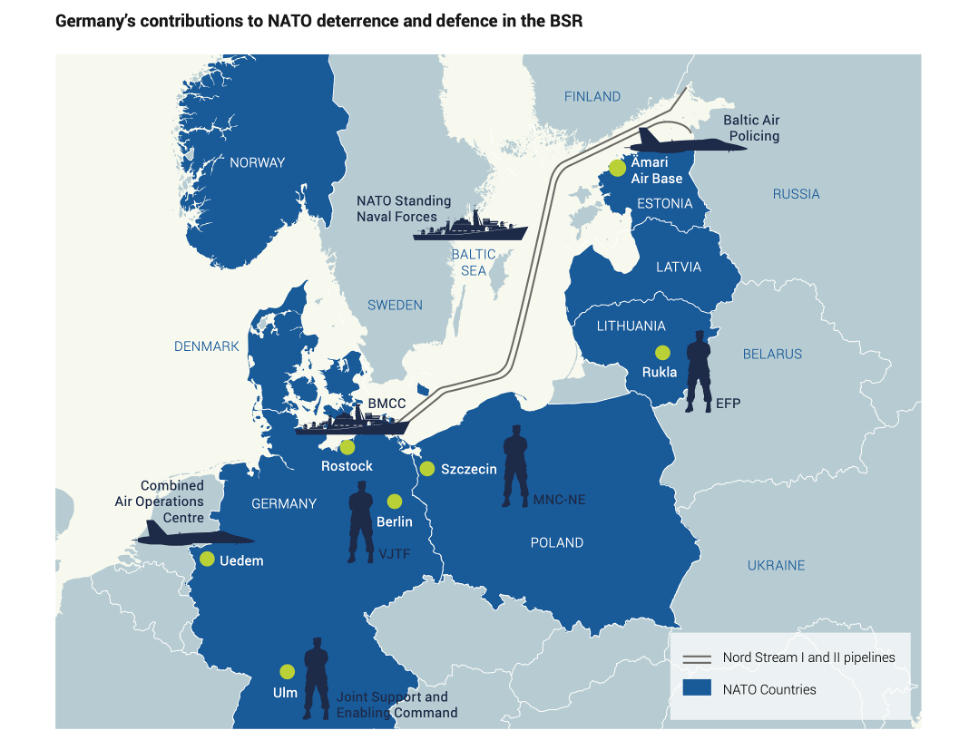

We might focus on the map which was created for the report on Germany and contributing to Baltic Sea Region security, and we can identify some of the areas where German military support and capabilities need to be able to flow.

It would make sense to think of Poland and Germany as a single defense area.

This has been difficult because of relations between the two states and their roles in the European Union, but from a defense standpoint I really think there is no other conclusion.

Second, there is the need to project power to the Baltic states and to provide for their defense and to provide for NATo defense in depth.

Third, there is the newly expanded defense perimeter of Northern Europe and the Baltic region.

This means both that Germany has new responsibilities but new opportunities as well to work with a more integrated Nordic defense. And this area highlights the opportunity to work integration across sea, air and land, which certainly has not been a strong point for Germany but is an inherent capability within the new ISR and C2 technologies being deployed and developed by Germany’s allies.

Fourth, there is what is not seen on this map, namely, the need to deal with the Central European states to the south and east of Germany.

Engagement in this area rapidly takes Germany to the Black Sea region, but one could argue that they are not the primary player here, but a contributor.

But that gets at the broader point: where should Germany concentrate its innovations?

Where should it focus on its re-set of capabilities?

And how to structure a relativistic strategy in light with its evolving capacities and requirements?

A key challenge facing any credible defense strategy is to correlate ends with means; and to ensure that core priorities are met. I have indicated what in my view this priorities might be, and will turn to the question of how to move evolving capabilities across the relevant European chessboard for Germany.

And here I am getting at a key point which can be easily missed in a defense rebuild: which platforms allow for the kinds of deployment flexibility required by the new warfighting approaches?

Put another way, Germany is not simply a repository of self-defense capabilities; it needs to be a launch pad for forward defense capabilities. And it is a challenging path to go from a low combat readiness force of limited means to shaping a kill web enabled mobile force capability to support forward defense and seam warfare.

Key Elements in Crafting and Building Out a Forward Defense for Germany

I have argued for some time that new technologies and new approaches to concepts of operations can allow U.S. and allied forces to work force integration across an extended battlespace to provide for a more lethal and survivable force.

It is also a question of affordability as the approach needs to ensure most effective use out of the force we have and leveraging effectively force transformation as we reshape our forces to ensure that they are at the key point of impact for combat, deterrence, and crisis management.

For Germany, this means reshaping and building out a force that can operate across the relevant regional battlespace which Germany needs to ensure protects its interests and contributes to enhanced allied defense in the region.

There are a number of key elements in shaping such an approach.

The first is really foundational is not focused on the defense platforms designed to deliver the lethal element for the combat force.

As I wrote with my co-author in our book on The Return of Direct Defense in Europe, shaping a sustainable security and defense capability is really about infrastructure, a domain in which the European Union can play a much more central role. It is about enhanced cyber capabilities, rebuilding road and rail networks to enable rapid movement of forces and supplies, shaping active and passive defenses within Germany so that the logistics supplies necessary to move forward are protected against direct attack, whether by longer range strike or terrorist attacks, a credible energy policy which responds to 21st century geo-politics rather than being mired in the green energy labelling debate, and stockpiling the parts and weapons which the active defense needs to sustain combat capabilities in case of conflict.

The second is to determine where Germany will forward position capabilities, such as in the case of the Baltic brigade, and to have ready forces able to reinforce these forward positioned capabilities. Associated with this is a more agile force able to be move forward to areas where Germany will not pre-position force, this means having integratable force able to seamless work with the relevant nations with whom Germany is supporting. This will be a function of ongoing exercises, shaping weapons commonality, and an ability to work with disparate national systems.

The third is to shape common ISR sharing capabilities not only across the German joint force but within the relevant coalition forces. I have written earlier about the changing nature of the ISR challenge which revolves around having the relevant information at the point of interest to take timely decisions.

The fourth is determining how to shape effective joint force German packages to be projected forward. How to shape evolving joint air-ground-maritime multi-domain forces? In this sense what German force rebuilding is facing is more akin to how the Marines project power than does the U.S. Army.

The fifth is how to sustain the force forward and to ensure that the force has a continuous flow of parts to the combat force to ensure high combat readiness as well as the fuel and weapons that it will need in a dynamic combat situation.

I am going to focus for the rest of this article on this fifth point.

How can Germany leverage its lift capabilities more effectively to deliver the kind of sustainment to a forward deployed force within Europe, and one which needs to be able to have mobile agile force capability as well?

This challenge is certainly not unique to Germany but it revolves around how to get full value out of it’s A-400M force, its C-130J force and adding a rotorcraft lift capability which extends both the capabilities of what Germany already has acquired and shapes an innovative way forward to support a forward deployed, agile and mobile combined arms force.

Leveraging an Enhanced Fixed Wing Lift Force Within the German Armed Forces

The A400M

Let me start with the A400M component of the lift force.

The Germans had originally ordered 53 of the aircraft but then the government announced that after accepting the first 40 aircraft they would sell the remaining 13 on order.

But then in 2019, the government reversed course and announced that the remaining 13 aircraft would be used to form a multinational airlift wing to be based in Germany.

The Luftwaffe used the A400M for the first time in combat in 2018 in Afghanistan.

And it played an important role in the evacuation from Afghanistan when President Biden decided on a precipitous withdrawal last year.

I have flown on the aircraft a couple of times and have spent time with the French Air Force at their A400 M base in France as well.

The aircraft has several impressive capabilities.

Modern aerospace technology on the aircraft makes it clearly a 21st century aircraft, and its three-man crew can operate an aircraft carrying an impressive load as well.

The engines allow for rapid lift from a variety of airfields, including very rough landing strips.

But the power of the turboprop engines has created a problem for one function which was desired for the aircraft, namely, rapid refueling of helicopters.

In fact, difficulties in this domain have led the French and the Germans to establish a joint C-130J force, a subject I will turn to in the next piece.

But it is really simply since around 2017 that the A400M has been making its presence known to the USAF and allied air forces, and the aircraft is clearly making an important contribution to the lift mission for the nations operating the aircraft and for their allies.

This shift from the Transall experience to the A400M one is suggestive of the shift which the Germans armed forces might consider when looking at its decision on lift to be provided by a new rotorcraft platform as well.

The Transall’s were initially delivered in the 1960s which is similar to the initial delivery of the Chinooks as well.

If you have moved on from the Transall, why would you by its generational equivalent in rotor lift?

The C-130J

The French and the Germans have built a joint C-130J squadron.

The decision to acquire the aircraft was to provide for a core capability which the A400M did not fill, but was a recognition that a wide-range of lift capability was needed to support forward deployed operations.

Many of the articles discussing the joint acquisition highlight that the J was being purchased to fill the gap which the retirement of the Transall opened up.

But the A400M was procured to fill this gap as well.

So the broader point is that lift is so important with its capability to support a multi-domain force, that you cannot fill the need with simply one platform.

And indeed, the J does things which the A400M cannot do, notably with regard to a wider range of helicopter refueling and an ability to fly into a wider range of landing locations.

And the bi-national squadron has indeed already operated to support forward defense in Europe, which is what I am arguing is the strategic thrust of any German defense reset. Given a focus on forward defense air lift and tanking in all its variants is crucial.

But it is also to ensure complete integration across the lift and tanking force as well.

Clearly, taking a joint squadron approach towards the C-130J by the French and the Germans supports that objective.

The German Vertical Lift Decision as Part of the German Defense Reset

Prior to addressing the platform options for the German defense force in terms of either a medium or heavy lift rotorcraft platform, I would like to summarize some considerations identified from the previous analyses of the German defense re-set.

First, the shift for a German defense reset is from a primary focus on territorial defense during the Cold War to forward defense of the perimeter of the wider German defense zone. This means that any rotorcraft addition to the lift fleet must move at distance with air refuelability a key requirement for sure.

Second, as logistics supply and an ability to move supplies to the operational force is at the heart of an effective sustainable deterrent and combat force, the role of an ability to move supplies is crucial. This is why working ground assets for such supplies, notably by rail is a key part of the way ahead.

And certainly, this makes the lift element even more important to support German forces forward or allied forces which German platforms are moving from rear to forward areas. This is also means that an ability to integrate the lift fleet is crucial.

Third, the entire lift force along with the ground transport elements needs to be exercised and developed to be able to move supplies to a combat force which operate from flexible or mobile basing.

In order to enhance the survivability of the force, moving supplies around an extended combat space is a key requirement. Adding a rotorcraft element to the lift force has as its primary focus an ability to support a distributed combat force, able to operate from a wide variety of mobile bases. The rotorcraft element has at its requirement an ability to move rapidly the maximum load out which a distributed force will need to have the level of lethality required.

Fourth, there is significant defense innovation underway, which will empower the evolving combat force and to which the new lift asset will need to contribute.

There are significant changes underway to enable unmanned systems, C2 and ISR distribution and integration and evolving mixes of unmanned systems with weaponization approaches. The new rotorcraft will need to have the capability to be a key enabler and participant in the evolving roles of the lift force as new technologies are added to the force, notably in terms an ability to work the evolving digital integration of a deployed distributed integrated force.

In other words, a platform decision going forward for the German armed forces should where possible be made to add capability which positions itself to work with the evolving force, rather than simply fitting into the inherited legacy force.

The Vertical Lift Choice from the Standpoint of the German Defense Re-set

If this was the Cold War, where the primary focus was really upon moving support around Germany to reinforce the direct defense of Germany, then there might be a compelling case for the legacy Chinook.

But that is not what Germany is facing in terms of the return of direct defense in Europe.

Germany faces the challenge of reinforcing their Baltic brigade, moving rapidly to reinforce Poland, and to move force where appropriate to its Southern Flank.

In the 2018 Trident Juncture exercise, German forces moved far too slowly to be effective in a real crisis, and it is clear that augmenting rapid insertion of force with lift is a key requirement for Germany to play an effective role.

This is where the CH-53K as a next generation heavy lift helicopter fits very nicely into German defense needs and evolving concepts of operations.

The CH-53K operates standard 463L pallets which means it can move quickly equipment and supply pallets from the German A400Ms or C‑130Js to the CH-53K or vice versa.

This is not just a nice to have capability but has a significant impact in terms of time to combat support capability; and it is widely understood that time to the operational area against the kind of threat facing Germany and its allies is a crucial requirement.

With an integrated fleet of C-130Js, A400Ms and CH-53Ks, the task force would have the ability to deploy 100s of miles while aerial refueling the CH-53K from the C-130J.

Upon landing at an austere airfield, cargo on a 463L pallet from a A400M or C-130J can trans-load directly into a CH-53K on the same pallet providing for a quick turnaround and allowing the CH-53K to deliver the combat resupply, humanitarian assistance supplies or disaster relief material to smaller land zones dispersed across the operating area.

The CH-53K has a narrower physical footprint than its predecessor though maintains the same fuel capacity and includes a 12” wider cabin giving greater capacity for the internal load 2 x 10,000lb AMC 463L pallets or 5 AMC 463L half-pallets, and drive-on loading a High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWV) or a European Fenneck armored personnel carriers—all with the troop seats still installed.

The 53K’s intermodal cargo system allows transfer of Air Mobility Command 463L pallets directly from fixed-wing transport aircraft (without the need for reconfiguration to wooden warehouse pallets) and lock them in place with an internal pallet locking system eliminating the need for the crisscrossing of cargo straps, significantly enhancing the speed of internal cargo operations and in-theater cargo throughput.

This drive-on loading of HMMWVs and similar width vehicle or loading of pallets without the need to physically remove troop seats, eliminates the associated delays while facilitating the ability for rapid, dynamic re-tasking of missions between trooplifts, internal cargo and external delivery. These true heavy lift internal features provide tremendous mission flexibility and efficiency in delivering combat power or in delivering Humanitarian Assistance or Disaster Relief for those in need.

Supporting the kind of distributed force which Germany and its allies are working to enhance survivability. but through shared C2 and ISR gaining the kind of integratability to deliver the lethality needed for a deterrent and combat force.

Similarly, after aerial refueling from a C-130J, the CH-53K using its single, dual and triple external cargo hook capability could transfer three independent external loads to three separate supported units in three separate landing zones in one single sortie without having to return to the airfield or logistical hub.

The external system can be rapidly reconfigured between dual point, single point loads, and triple hook configurations, to internal cargo carrying configuration, or troop lift configuration in order to best support the ground scheme of maneuver.

If the German Baltic brigade needs enhanced capability, it is not a time you want to discover that your lift fleet really cannot count on your heavy lift helicopter showing up as part of an integrated combat team, fully capable of range, speed, payload and integration with the digital force being built out by the German military.

It should be noted that the CH-53K is air refuelable; the Chinook is not. And the CH-53 K’s air refuelable capability is built in for either day or night scenarios.

A 2019 exercise highlighted the challenge if using the Chinooks to move capability into the corridor. In the Green Dagger exercise held in Germany, the goal was to move a German brigade over a long distance to support an allied engagement. The Dutch Chinooks were used by the German Army to do the job. But it took them six waves of support to get the job done.

Obviously, this is simply too long to get the job done when dealing with an adversary who intends to use time to his advantage. In contrast, if the CH-53K was operating within the German Army, we are talking one or two insertion waves.

And the distributed approach which is inherent in dealing with peer competitors will require distributed basing and an ability to shape airfields in austere locations to provide for distributed strike and reduce the vulnerabilities of operating from a small number of known airbases.

Here the CH-53K becomes combat air’s best friend. In setting up Forward Operating Bases (FOBs), the CH-53K can distribute fuel and ordnance and forward fueling and rearming points for the fighter aircraft operating from the FOBs.

Being a new generation helicopter it fits into the future, not the past of what the Bundeswehr has done in the Cold War. It is not a legacy Cold War relic, but a down payment on the transformation of the Bundeswehr itself into a more reactive, and rapid deployment force to the areas of interest which Germany needs to be engaged to protect its interests and contribute to the operational needs of their European allies.

From an operational standpoint, the K versus the E or the Chinook for that matter, offers new capabilities for the combat force. And from this perspective, the perspective of the two platforms can be looked at somewhat differently than from the perspective presented in the Thompson article.

Next generation air platforms encompass several changes as compared to the predecessors which are at least thirty years old or older, notably in terms of design. Next generation air platforms are designed from the ground up with the digital age as a key reality.

This means that such systems are focused on connectivity with other platforms, upgradeability built in through software enablement and anticipated code rewriting as operational experience is gained, cockpits built to work with new digital ISR and C2 systems onboard or integratable within the cockpit of the platform, materials technology which leverages the composite revolution, and management systems designed to work with big data to provide for more rapid and cost effective upgradeability and maintainability.

Such is the case with the CH-53K compared to its legacy ancestor, the CH-53E or with the venerable legacy Chinook medium lift helicopter.

Comparing the legacy with the next generation is really about comparing historically designed aircraft to 21st century designed and manufactured aircraft. As elegant as the automobiles of the 1950s clearly are, from a systems point of view, they pale in comparison to 2020s automobiles in terms of sustainability and effective performance parameters.

To take two considerations into account, the question of customization of the German and Israeli variants and the question of sustainability both need to be considered with next generation in mind.

With regard to customization and modernization, digital aircraft provide a totally different growth path than do a legacy aircraft like the CH-53E or the CH-47.

Software modifications, and reconfigurations can provide for distinctive variants of aircrafts in a way that legacy systems would have to do with hardware mods.

And with regard to security levels of information flows, software defined systems have significant advantages over legacy systems as well.

With regard to sustainability, NAVAIR and the USMC have taken unprecedented steps to deliver a sustainable aircraft at the outset.

With the data generated by the CH-53K, the “smart” aircraft becomes a participant in providing inputs to a more effective situational awareness to the real performance of the aircraft in operational conditions, and that data then flows into the management system to provide a much more realistic understanding of parts performance.

This then allows the maintenance technicians and managers to provide higher levels of performance and readiness than without the data flowing from the aircraft itself.

Put in other terms, the data which the aircraft generates makes the aircraft itself an “intellectual” participant in the sustainment eco system.

This is certainly not the case with legacy aircraft which were not birthed in the digital software upgradeable world.

The next generation system which the CH-53K represents brings capabilities to the challenges which Germany faces in terms of getting force rapidly to the point of attack or defense required by the Bundeswehr.

German ground capabilities as provided by infantry armored vehicles, or ground artillery pieces, can be moved by the CH-53K with its unprecedented external lift capabilities, while carrying support elements inside the aircraft at the same time.

And the addition of the F-35 along with the current operation of the C-130Js provides the German forces with the same kind of insertion package which the Marines are working with to enable significant movement of insertion forces throughout the expanded battlespace.

The Germans have acquired C-130Js for among other reasons, to be able to refuel, fixed wing and rotorcraft, and are working with the Marines in training to operate their C-130Js in a variety of mission roles. It certainly is clear that the Marines operate their C-130Js in a wide variety of missions, and by training with the Marines, the Luftwaffe can easily transition to training for a similar range of mission options.

With the Germans operating the same three aircraft as the USMC, the Germans can train with them to provide for an ongoing common force insertion concept of operations.

And as both forces will operate throughout the Nordic, Baltic, Polish and East European regions, such common capabilities provide for a force multiplier for both the German and U.S. forces involved in European direct defense. Certainly, pooling of supplies and of maintenance capabilities could be worked as well.

It is no longer about defending against breakthroughs in the Fulda Gap; it is about moving force rapidly to make a difference in a time urgent combat setting on Germany’s periphery and flanks.

Simply buying legacy systems and leaving networked capabilities to show up in a future FCAS really misses the point; integratability has to be built in which it clearly is with the CH-53K.

It is a down payment on building out the kind of networked force Germany has committed itself too with its FCAS commitment.

Put in other terms, platform choices should be considered as well from the vantage point of whether or not that platform choice advances the integratable force able to move rapidly to the point of attack or defense or not.

From this standpoint the choice is clear: The Chinook represents the Cold War past; the CH-53K the future of the integratable force.

With the shaping of a new force structure within the context of the current and projected security context for Germany, it makes sense that each new platform or program be made with regard to where Germany is headed in terms of its 21st century strategic situation, and not be limited by the thinking of the inner-German defense period.

This article provides a summary of our recently released report on the German defense reset and its implications for a vertical lift platform acquisition for the German defense forces but for the full argument, readers should read the full report.

For a PDF version of the report, see the following:

German Defense Re-set

For an e-book version of the report, see the following: