By Pierre Tran

Paris – There are difficulties in reaching an industrial agreement to build a technology demonstrator for a future European fighter jet, Guillaume Faury, chairman of the Gifas aerospace trade association, said April 28.

The phase 1B for the Future Combat Air System was “difficult,” he said at a press conference of Groupement des Industries Françaises Aéronautiques et Spatiales, which gave a review of 2021 for the French aerospace industry.

Faury is also chief executive of Airbus, the European manufacturer of airliners.

A contract for that critical phase 1B has yet to be signed, holding up the building of a demonstrator for a next generation fighter, the key element in the FCAS project backed by France, Germany and Spain.

That delay stems from prime contractor Dassault Aviation insisting on clear leadership in managing the fighter project, while industrial partner Airbus Defence and Space seeks a high level of cooperation, effectively equal status.

The fighter demonstrator is due to fly in 2027, but there appears to be little progress in resolving a deep divide, reflecting the distinct management cultures of the family-controlled Dassault and Airbus, which prides itself as a European company working in close partnership rather than a subcontractor.

Asked if there was room for the British Tempest fighter project to join FCAS, to avoid there being two rival European fighter jets, Faury said there would be three fighters with the F-35, which is a “great success” in Europe.

FCAS is still a project exploring the technology, not yet a program, he said, and there are already three partner nations. It is, effectively, too early to say.

“We have to win on FCAS,” he said, as that will give critical mass to Europe, which seeks sovereignty through cooperation in defense and security. The Ukraine crisis pointed up the importance of that European pursuit of capability.

There was a German election last year, and this year France has gone to the polls, which may have had an effect on the FCAS timetable.

A French election returned April 24 Emmanuel Macron to a second five-year term as president, with 58.54 percent of the vote, beating far-right candidate Marine Le Pen, who won 41.46 percent.

There will be a parliamentary election in June, with pollster Harris Interactive predicting Macron winning support from a center-right majority in the lower house National Assembly.

Ukraine War As Stimulus

The Ukraine crisis points up the importance of the pursuit of sovereignty, and European cooperation needs to be speeded up, Faury said. The European Council, the policy-setting institution for the European Union, supports the drive for European defense cooperation, and Berlin backs that European quest.

German chancellor Olaf Scholz has said Berlin is buying the F-35, and also said Germany will pursue the FCAS with France, he said.

Individual nations lack the means to pursue their own fighter programs, he said, pointing up the need for the “European dimension” and the importance of FCAS.

It is worrying that Germany plans to spend heavily on non-European weapons, he said, and there should be consideration of the long term prospects for European industry. Faury was answering a question on Berlin’s plans to buy the F-35, the Israeli Arrow 3 missile and U.S. Chinook heavy transport helicopter.

On European cooperation, there is the contract for the “Euro drone” a few months ago he said, referring to the €7.1 billion deal for a European medium-altitude, long-endurance unmanned aerial vehicle, with Airbus DS as prime contractor.

Airbus DS has selected the Catalyst engine from Avio, sparking dissent, as the Italian company is a unit of a U.S. company, General Electric, while a rival offer led by Safran Helicopter Engines, a French company, was rejected.

Safran HE had teamed up with Italian partner Piaggio Aerospace, German firms MT-Propeller and ZF Luftfahrttechnik, and Spanish manufacturer ITP.

France, Germany, Italy, and Spain backed the European drone in a bid to cut dependence on Israeli and U.S. for UAVs, seen as an important system.

There has been an op ed on the business website La Tribune and those on a social media platform calling for France to ditch Germany as partner nation, as Berlin has gone its own way in ordering weapons.

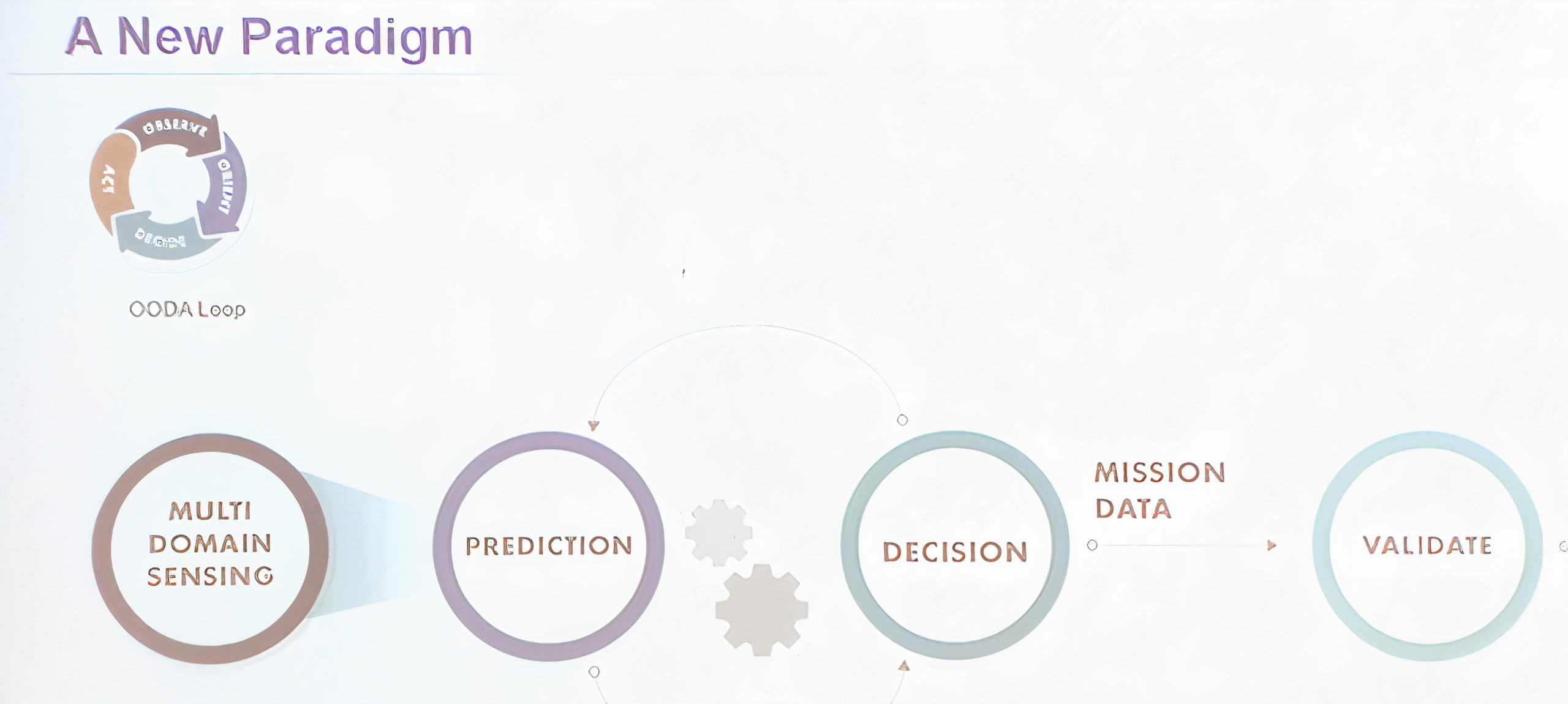

The new fighter is the key pillar in the seven pillars of technology underpinning the FCAS project, with partner companies signed up to work on those six other sectors. The other six pillars are the engine, remote carriers – or drones, combat cloud for network communications, simulator labs, sensors, and stealth.

Each of the partner companies negotiated its role in those pillars, such as Airbus, Thales, and Indra reaching agreement on their work share on the combat cloud, a network intended to hook up the new and legacy fighters, remote carriers, and allied aircraft. It remains for Dassault and Airbus DS to reach agreement on phase 1B on the demonstrator for a new fighter.

The FCAS phase 1B is reported to have a budget of €3.6 billion ($3.8 billion) and runs 2021 to 2024, while phase 2 runs 2024 to 2027, with a budget of €5 billion, backed by the three partner nations.

The war in Ukraine has prompted a rethink on the corporate social responsibility of arms manufacturers, Faury said, which have seen it hard to raise financing due to concerns over CSR.

“Ukraine has changed the cards,” he said, with sovereignty seen as key to resilience.

Signs of Recovery

GIFAS reported 2021 sales of €55 billion, up 7.2 percent from a year ago, with exports accounting for €37.3 billion, Faury said. Civilian aircraft accounted for 65 percent of sales.

Military aircraft saw a strong rise in sales, worth €19.5 billion, up 18 percent from the previous year. Military export sales rose 24 percent to €10.3 billion, while domestic military sales rose 13 percent to €9.2 billion.

Military orders jumped 140 percent to €27.6 billion, with exports worth €11.7 billion, up 258 percent. Domestic orders rose to €15.9 billion, up 92 percent.

“Major success” in military orders stemmed from deals for the Rafale fighter jet for Croatia, Egypt, Greece, and the United Arab Emirates.

In helicopters, France ordered the light joint helicopter HIL Guépard, and the UAE ordered the H225M Caracal.

Indonesia and Kazakhstan ordered the A400M military transport, while Spain and the UAE ordered A330 multirole tanker transport aircraft.

In 2022, Indonesia and Greece ordered Rafales, while last year Saudi Arabia ordered civil helicopters.

Overall orders last year rose 68 percent to €50.1 billion, with military orders accounting for 55 percent, a highly unusual proportion as civil orders usually outweigh the defense sector.

The book-to-bill ratio of overall sales to orders was close to 1:1, he said.

Return of the Paris Air Show

“We shall return,” Patrick Daher, chairman of SIAE, the organization which runs the Paris air show, told the press conference. Daher was referring to the pledge made by Gen. Douglas MacArthur as the U.S. forces withdrew from the Philippines in the second world war.

The Paris air show will re-open in 2023, having been forced to cancel last year’s exhibition due to the Covid pandemic. The air show next year will mark the “start of the recovery,” Daher said, pointing to a festive spirit planned for the weekend when the high profile exhibition opens to the public.

The show organizer expects to attract 177,000 public visitors, the same level as the 2019 show.

The air show serves as an important means to attract and train a skilled work force for the aerospace industry. Gifas is looking to recruit 15,000 workers this year, but finds it hard to recruit women. The trade body has launched a brand name, Aéro Recrute, to boost the hiring drive.

The air show organizer also seeks to boost business for start-up companies, and there will be exhibition space named Start Air.

Dassault and Airbus DS held a joint press conference at the 2019 air show, with respectively executive chairman Eric Trappier and the then chief executive Dirk Hoke standing next to a life size model of the next generation fighter.

The unveiling of that model, with French, German and Spanish defense ministers signing a cooperation agreement, was the media high point for European military aeronautics.

It remains to be seen whether there will be a joint press conference at the 2023 Paris air show, with a similar upbeat note.

The Paris air show is due to run June 19-23 next year.

Credit Photo: GIFAS: Guillaume Faury, Président du GIFAS, a présenté le jeudi 28 avril 2022, les résultats 2021 de l’industrie française aéronautique, spatiale et de Défense.