By Robbin Laird

In my article on meeting the challenge of contested operations and C2, I laid out the nature of the challenge and why meeting the challenge is crucial to combat effectiveness in conflict with peer competitors.

I concluded that article with this characterization of the challenge: “How might we accelerate the strategic innovation we need to deliver the force connectivity and C2 for a distributed but integratable force?

“And to do so in the face of engaging in conflict with nuclear-armed authoritarian powers?”

One approach to providing a near term solution which lays down a solid foundation for further development is Cubic Corporation’s HaloTM system. Halo has been developed with the USAF as its initial customer to provide capabilities for the USAF’s Joint All-Domain Command and Control or JADC2 effort. The initial HaloTM system is being tested on the USAF High-Capacity Backbone (HCB) program and is projected to deploy on various aircraft and platforms.

The fact sheet for the system provides a description of the system which is a bit complicated:

“Halo solves a critical communications challenge for warfighters at the edge: delivering reliable, high data rate service in a scalable, heterogenous network. Its robust, software-defined, digital beam-forming antenna system delivers secure video, voice, and data, transporting data through a joint, all-domain mesh network. The result is revolutionary: providing our warfighters with a demonstrable battlespace advantage.”

But hidden in that language is a solution to the problem which I framed in the article on contested operations and C2. To clarify the nature of the system, and how it worked to solve this key challenge, I talked with David Harris, Cubic’s VP and General Manager of Secure Communications, about the Halo system and its capabilities and how it provides an answer to this challenge by providing a reliable internet-like experience for warfighters in all environments.

Harris has an interesting background which certainly has prepared him to work the secure communications challenge for a distributed but integratable force. He started as a U.S. Navy officer and his first job in industry was with Northrop Grumman where he was program manager talking the problem of how to get information off a fifth-generation fighter to legacy fighters and the joint force.

In this role, he spent a lot of time with F-22 pilots and as they worked the data transfer challenge, a key role of a data rich aircraft for the air combat force became evident to the F-22 community.

As Harris put it: “I spent a lot of time with F-22 pilots, and they never really gave any credence to wanting any help. Because the F-22 is stealthy, they don’t want to do anything where anyone knows where they’re at or what they’re doing. And through the course of my engagement with them, it really opened their eyes to just how much help they could get if they could share the data in a real-time protected fashion.”

He continued working in the fifth-generation world at Northrop where he worked on F-35 CNI and MADL. The focus was upon how to meet the challenge of taking what the F-35 does as a wolfpack and how it can expand its support to the rest of the aerospace platforms working in the contested battlespace.

He then moved into the world of working black program multi-domain communications where, in his words, “we focused on building out a multi-layered network capability to support multi-domain functions on these platforms, and be able to provide high bandwidth, secure, resilient capabilities for them.”

With this background, clearly his experience provided a nice entrance into the JADC-2 world, where Halo is initially positioned.

What then is Halo?

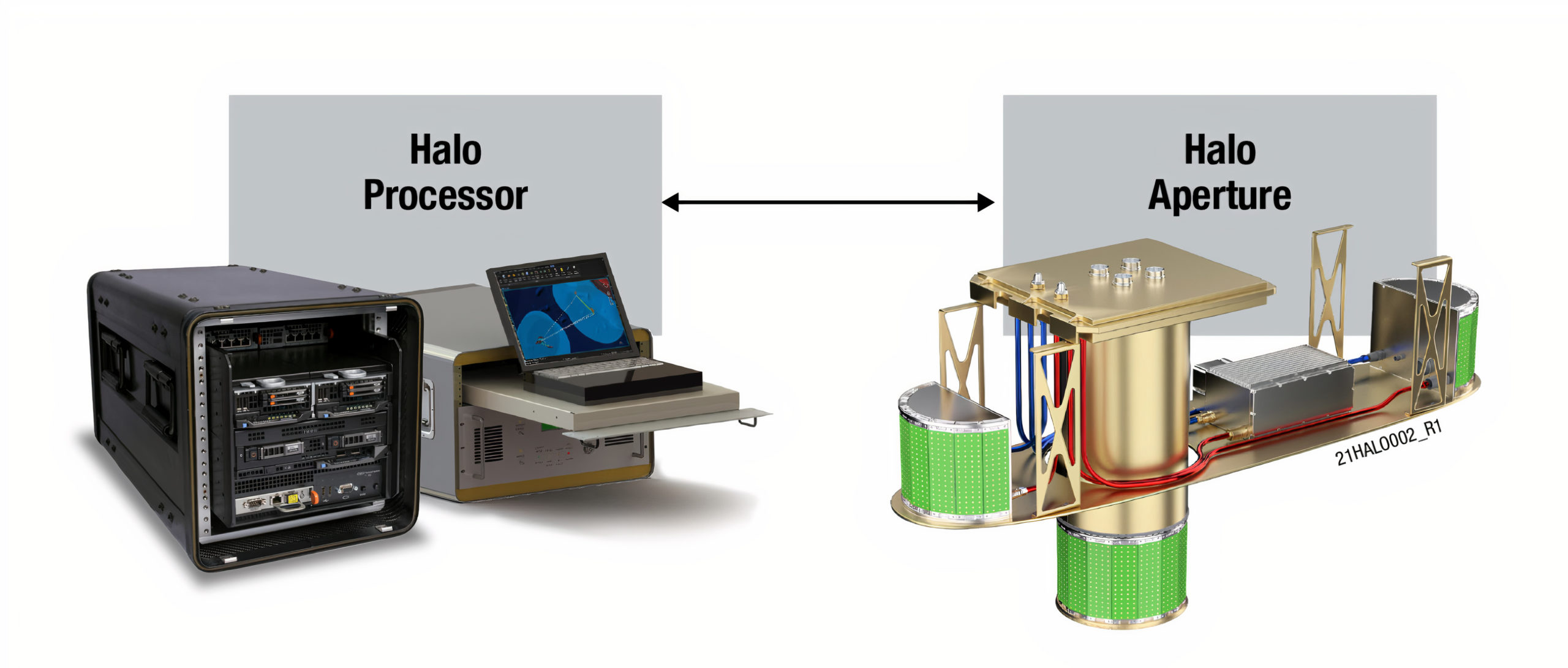

Halo as a system can be seen in the Cubic graphic below:

The Halo system consists of two packages working together: the processing system and the aperture system which are fully integrated with one another. The aperture is a software defined digital beam forming system.

This is how CUBIC has described the two packages and how they work together:

“Halo eliminates the need for crowded antenna farms with its one low-profile antenna. This single aperture delivers many links and yields a significant SWaP-C per link advantage. Halo can “copy/paste” multiple beams in software, providing individual directional beams to each network node, thereby suppressing an adversary’s ability to intercept communications and detect platforms.

“Halo’s powerful digital processing capabilities enable automated discovery and spatial networking. This capability establishes a resilient GPS independent network that provides adaptive link management and dynamic network routing. Its pure digital beam technology processes faster and more effectively than analog or hybrid beam-formers.”

This is how Harris described HaloTM and its approach.

HaloTM is built upon established military waveforms, open standard wave forms. If the military users have an existing radio that speaks one of those waveforms, such as CDL, or BE-CDL (including the new protected mode of BE-CDL), they’ll be able to connect to Halo and leverage those services within the constraints of their end point.

“You’ve probably seen JADC2 pictures, where you’ve got the tankers and other large aircraft that have multiple connections coming out of a single aircraft. The power of Halo is really revolutionary in that you can have five, six, seven, eight, essentially an unlimited, number of connections from this single system, this single aperture.

“But you don’t need that capability throughout the entire fleet. The guy on the ground with his handheld radio or system doesn’t need to connect to everything around him. If he can reliably and assuredly connect to a single point, and leverage the whole network through that single connection, you don’t have to have the resources dedicated to have a Halo at that point.

“It really is about the open waveforms and leveraging those so that we don’t have to rebuild the entire infrastructure to take advantage of this.”

One way of understanding the nature of Halo as a system is to compare it with legacy capabilities. Here is how Harris explained the differences. “Within a single aperture, we can have n links established. Although we’re not the only ones doing digital beam forming, we are doing it in a new and transformational way.

“There are other digital beam forming technologies out there. But with the Halo system, we have the ability to be able to cover the entirety of the airspace with one device. And in the upcoming USAF High-Capacity Backbone demo, we’re going to do eight simultaneous high bandwidth, resilient, secure links out of the single device.

“That is to say, the modified legacy approach is to stack four modems on each other and carving out space for each link. It’s taking old school technology and trying to apply it to work in today’s problem. Halo is all about focusing on today’s problem with capabilities which build out to the future.

“Halo was built from the ground up to be able to do something that’s never been done before. And it does it in a resilient capacity. It’s not reliant on other layers and other capabilities to be able to build up this network. It’s automated. It happens without user intervention. It doesn’t rely on other signals or capabilities to be able to build up the network and find other connections out there.

“One doesn’t have to be another Halo in the battlespace to do this. One needs to have a system that’s speaking the right language, the right waveform.

“And Halo autonomously builds a network. When the network is built, it then has the smarts to figure out how to optimally use that network.

“Halo is looking at all the various connections it has to every point of the network and figuring out, “How do I get the data there in the most optimal fashion? And if a plane on which the Halo system resides turns and you get blockage, how do I reroute it through other things? How do we keep this going without any kind of user intervention?”

“Halo has been built around embracing an open standard so that we can leverage the capabilities of everyone and be able to keep it that way for a long time. The system delivers really low SWaP per dollar of capability.

“The capability you get out of a singular device is leaps and bounds, an order of magnitude from both a cost, a size, and a weight, and a power perspective lower than anything else out there right now.”

In the next article, I will look at the broader implications of how HaloTM is not simply a node in a network but can deliver networks to the deployed force at the tactical edge.

This technology provides distributed force integration through C2 innovations and needs to get out to the force sooner rather than later.