By Pierre Tran

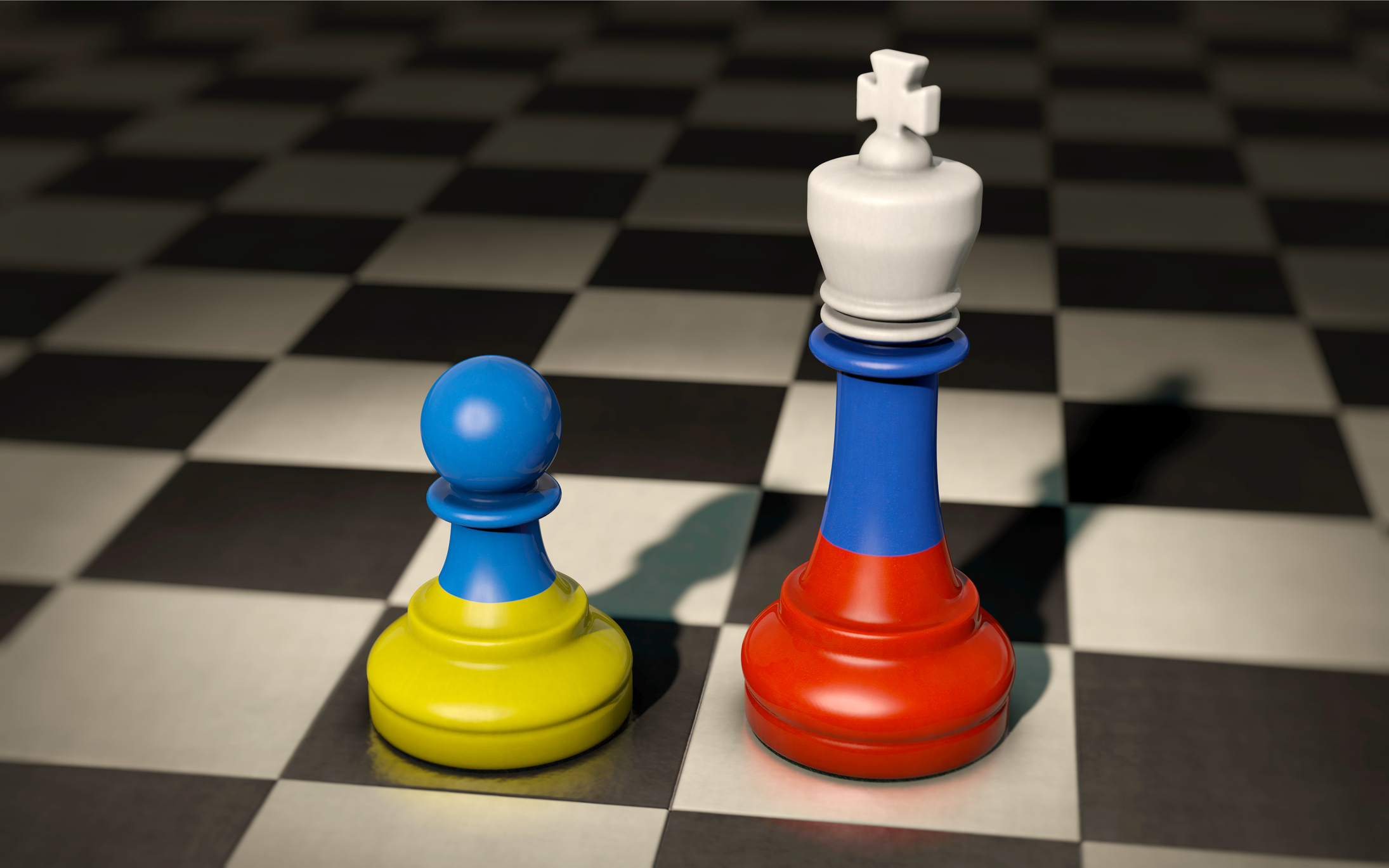

Paris – “The fate of not only our state is being decided, but also what Europe will be like,” the president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, said Feb. 24.

Zelenskiy was addressing the nation on the day of the Russian early morning missile attacks on the East European nation, followed by assault on land, sea and air ordered by Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Ukraine was offering assault rifles and urged people in Kyiv to prepare Molotov cocktails, as Russian troops entered the northern suburbs the following day.

Zelenskiy’s remark raised questions on whether the Russian assault on a democratic sovereign state would bring change in the European architecture for security and defense, and what those reforms might be.

The Russian offensive raised a range of security issues, such as how to deal with energy dependence, Russian food supply, and the need to deal with cyber warfare.

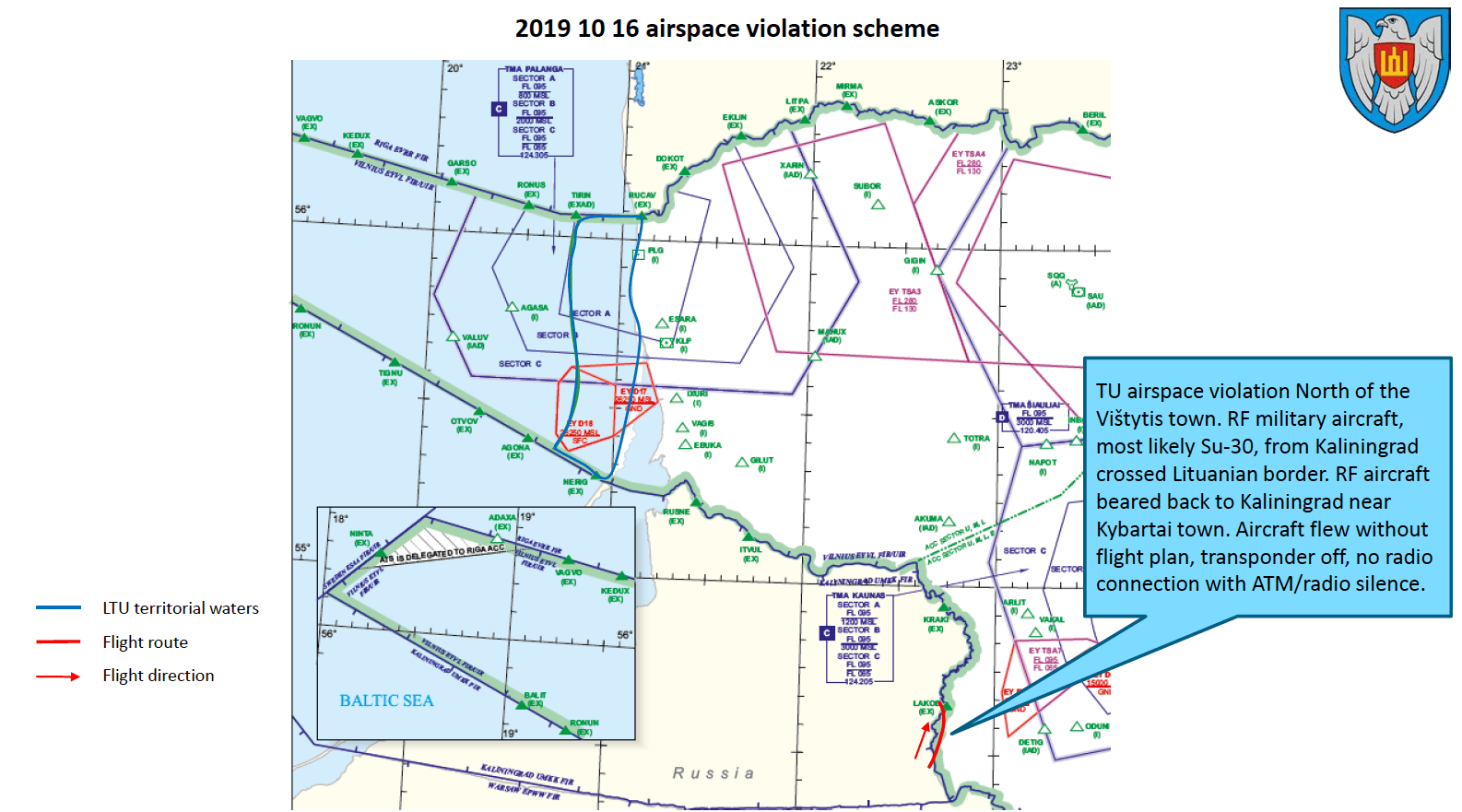

On the military front, there might be questions on deployment of Nato troops and missiles in central Europe and the Baltic nations, members of the alliance.

“This changes everything,” Timothy Garton Ash, professor of European studies at Oxford University, said Feb. 24 on BBC Radio 4. “We have to fundamentally rethink how we approach Russia, how we approach European security, how we approach a larger global architecture.”

“Peace on our continent has been shattered,” Nato secretary general Jens Stoltenberg said Feb. 24.

While Ukraine was not in the transatlantic alliance, Nato was holding Feb. 25 an emergency virtual meeting of heads of state and government of the 30 member states, to decide how to respond to the Russian assault.

Food, Energy Security

On the broad security front, Putin ordered investment of $52 billion in Russian agriculture, to cut reliance on food imports, website La Tribune reported.

Russia effectively held a “food weapon,” said Henri Biès Peré, head of the FNSEA farmers union, with 18 percent of the world wheat market, the report said. By grabbing Ukraine, which held 12 percent, Moscow controlled a third of the world market.

The Western nations had banned food exports among sanctions, in response to Russia seizing the Crimea region, eastern Ukraine, in 2014. That prompted Russia to become a leading wheat exporter after previously relying on imports.

Russia was also self-sufficient in poultry and almost so in pork production, following investing in industrial farming.

With lower quality standards, Russia grabbed market share from French wheat producers, who had been market leaders in Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, and Turkey. Russia had also won a share in Asian markets.

That strategy had political significance, as those nations would not “bite the hand that feeds them,” and could be considered “natural allies,” the report said.

In energy, Europe relied on Russia for some 40 percent of natural gas, with Germany vulnerable due to a switch away from nuclear power and plans to abandon coal by 2030.

Berlin suspended Feb. 22 a controversial certification of the Russian Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, worth $11 billion, and U.S. sanctions include the main contractor on the pipeline, Nord Stream AG, a Swiss-registered company, a unit of the Russian energy giant Gazprom. The industrial partners on that Russian pipeline, which bypasses Ukraine, comprise the French state-owned company Engie, Shell, Austrian firm AMV, and German companies Unipo and Wintershall DEA, Reuters reported.

That German suspension was just for now, but raised the question how Europe, and in particular Berlin, would tackle long-term dependence on Moscow.

The use of energy as a weapon for power projection could be seen with the International Energy Authority accusing Moscow of cutting 25 percent of gas supply in recent winter months, fuelling price rises to record highs in Europe.

Win the Information War

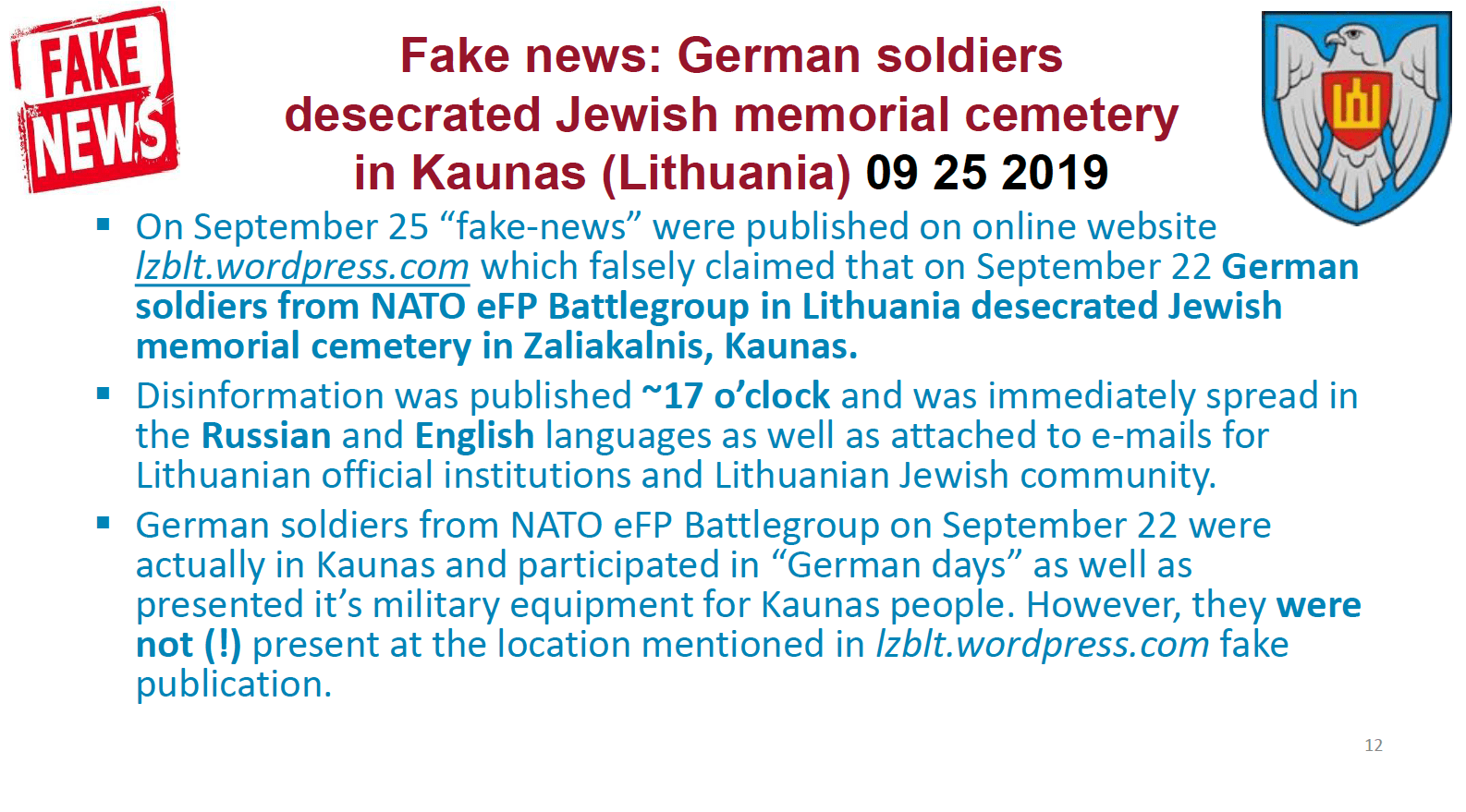

The French chief of staff, Army Gen. Thierry Burkhard, told Oct. 1 reporters there was need “to win the war before the war begins.”

Burkhard, a paratrooper who was previously spokesman for a previous chief of staff, pointed up the need to tackle the information war, and to train the services for “high intensity warfare.”

The opponents spread false information in a time of competition, contestation, and confrontation, and it was no more peace, crisis, and war of former times, he said.

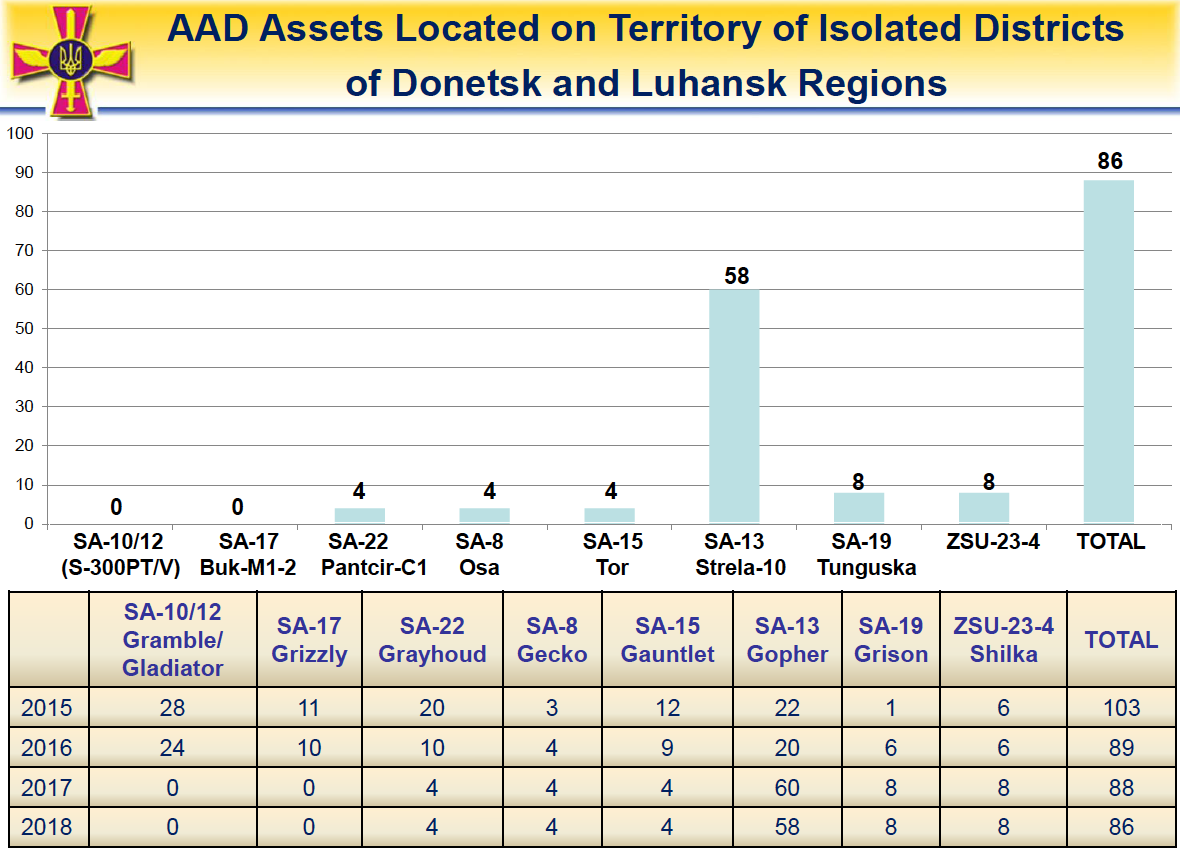

There was also need to adapt the services from the asymmetrical warfare on the Barkhane mission in the Sahel sub-Saharan region, he said, where French troops did not receive incoming artillery fire, and pilots did not fly against air defense systems.

Russian forces fired cruise missiles, flew fighter jets, and their troops seized or destroyed 80 military sites on the first day of the assault on Ukraine.

France to Send Weapons to Ukraine

“We are in contact with the Ukraine authorities to supply them with the defense equipment they need,” French president Emmanuel Macron said in a formal written address read out Feb. 25 for him to both houses of parliament.

France was making further commitments to Nato “to protect the territory of our Baltic and Romanian allies,” he said, and would bolster the fight against manipulation of information and cyber attacks from foreign powers.

Macron had earlier met former heads of state François Hollande and Nicolas Sarkozy before the solemn parliamentary address.

“The present crisis stems from the decision planned, decided and organized by Russia to invade Ukraine,” Macron said. France would adopt sanctions, which would have consequences for Russia and France.

The sanctions would show that Europe was not a union of consumers but a political project tied to values and principles held in common, he said.

“It is in this way the European Union must truly become a more sovereign power in energy, technology, and the military,” he said.

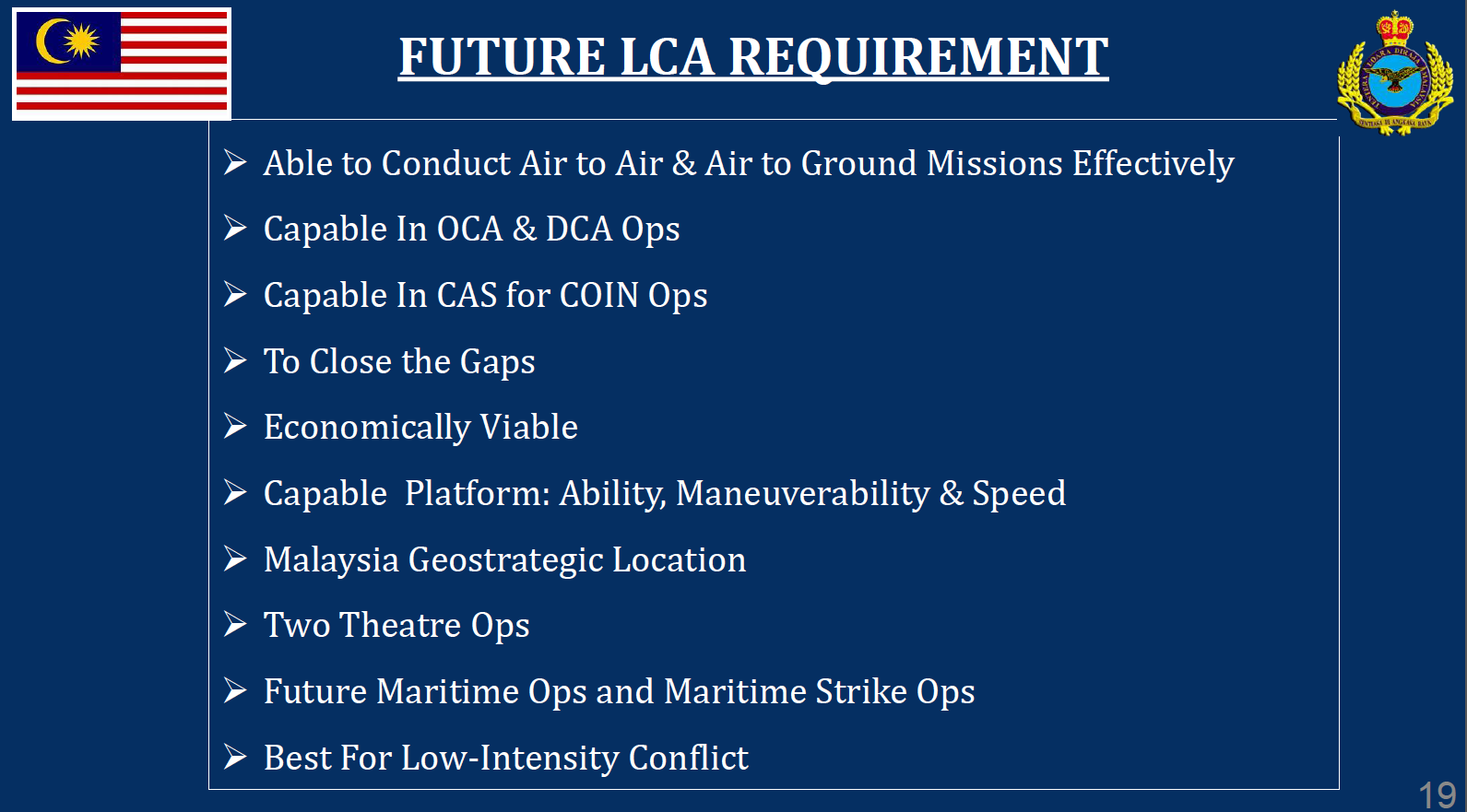

Ukraine would welcome delivery of weapons such as patrol boats, armored vehicles, and Caesar artillery, parliamentarian Jean-Charles Larsonneur told Feb. 23 the Association des Journalistes de Défense press club in a phone briefing.

Intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance missions were important and France flies ISR missions from Romania, he said. Larsonneur delivered a report on Ukraine to the defense committee of the lower house National Assembly.

France, since Jan. 1, is the lead nation in Nato’s very high readiness joint task force, set up in 2014 following Russia’s attack on Ukraine and Middle East crises.

In Nato’s enhanced forward presence, there are four multinational battalion-sized battle groups rotating through Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. There is also a Nato multinational brigade based in Romania.

Macron told the Nato summit France will send in the next few weeks 500 troops to Romania as the “lead nation,” with other Nato partners free to deploy soldiers, and also 200 troops to Estonia, alongside a British and Danish deployment, the spokesman for the armed forces ministry, Hervé Grandjean, told television channel BFM TV.

France was also as of Feb. 25 flying from France two air patrols a day, comprising two Rafale fighters and an A330 MRTT inflight refueling tanker in each patrol, he said, with the patrols flying on the eastern flank of Poland as part of a Nato air defense mission.

In mid-March the French air force will send four Mirage 2000-5 fighters to Estonia, with some 100 personnel, he said. These French deployments were intended as signs of “reassurance” to Nato members close to Ukraine.

Macron had discussed a fresh look at European security when he met Feb. 7 Putin in Moscow in a bid to “de-escalate” the crisis.

Macron spoke to Putin on the night of Feb. 24, with an exchange direct and brief, Le Monde reported.

Business Sanctions

The European Union, the U.K, and the U.S. were adopting a fresh batch of sanctions against Russia, which included freezing foreign accounts of Russian banks, suspending Aeroflot airline flights over Britain, and assets held by Russian parliamentarians and oligarchs close to Putin.

The Ukrainian foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba, criticized the EU for declining to suspend the Swift system of interbank transfers for Russia.

“I will not be diplomatic on this,” he said on a social platform. “Everyone who now doubts whether Russia should be banned from Swift has to understand that the blood of innocent Ukrainian men, women and children will be on their hands too. BAN RUSSIA FROM SWIFT.”

Stock in Thales, an electronics company, was one of the rare shares which rose Feb. 24, when financial markets fell on concerns over the Russian invasion.

Thales had sales in Russia of less than one percent of total turnover, a spokesman said, with some 130 staff in that country. Some 100 personnel worked in the civilian digital, identity and security unit, which handled bank cards and SIM cards.

In aeronautics, Thales supplied cockpits for aircraft including the Sukhoi Superjet 100 regional jet, and components for space projects.

Safran, which builds aero-engines, received half its titanium from the Russian company VSMPO, executive chairman Olivier Andriès said Feb. 24, reporter Vincent Lamigeon said on social media. The French company would speed up diversification of supply but was presently relying on VSMPO. Safran had built up its stock of titanium and had enough until autumn.

Rolls-Royce, a British engine maker, relied on Russia for 20 percent of its titanium and was also looking for other sources of supply, Reuters reported.

Dassault Aviation was understood to have sold the Falcon business jet in Russia but no details were available.

Rearming Europe?

A fresh debate on rearming Europe was likely, Mark Leonard, director of the European Council for Foreign Relations, said in a note Lessons for Europe from Munich Security Conference 2022. Such a discussion was all the more likely if Russia stored nuclear weapons in Belarus.

How Turkey would balance its ties to Russia and the West was one of the issues, he said, and what was the outlook for EU member state Hungary.

“European leaders coming out of the Munich Security Conference 2022 should focus on how to invent a new West in which they are less infantilised and can actively shape the new rules of engagement that will emerge from this crisis,” said Jana Puglierin, head the ECFR Berlin office and senior research fellow.

ODESSA, UKRAINE – 20 FEB 2022: Unity march in Odessa against Russian invasion. Man with placard about russian army

“Only Russian conscripts afraid of Russian army.”

Credit: Bigstock