By Robbin Laird

A key element of the presentations and discussions at the 1 December 2021 Williams Foundation seminar on building out sovereign capabilities was how Defence could best position itself to nurture, leverage and work with the evolving Australia space industrial eco-systsem.

AIRCDRE Terry van Haren (Retd.), former air attaché to the United States, provided a very clear focus on how he thought the ADF can best leverage an Australian space enterprise.

His focus was upon the emergence of “new” space which he had observed in the United States and the significant opportunities which such a strategic shift in the space business provided for Australia.

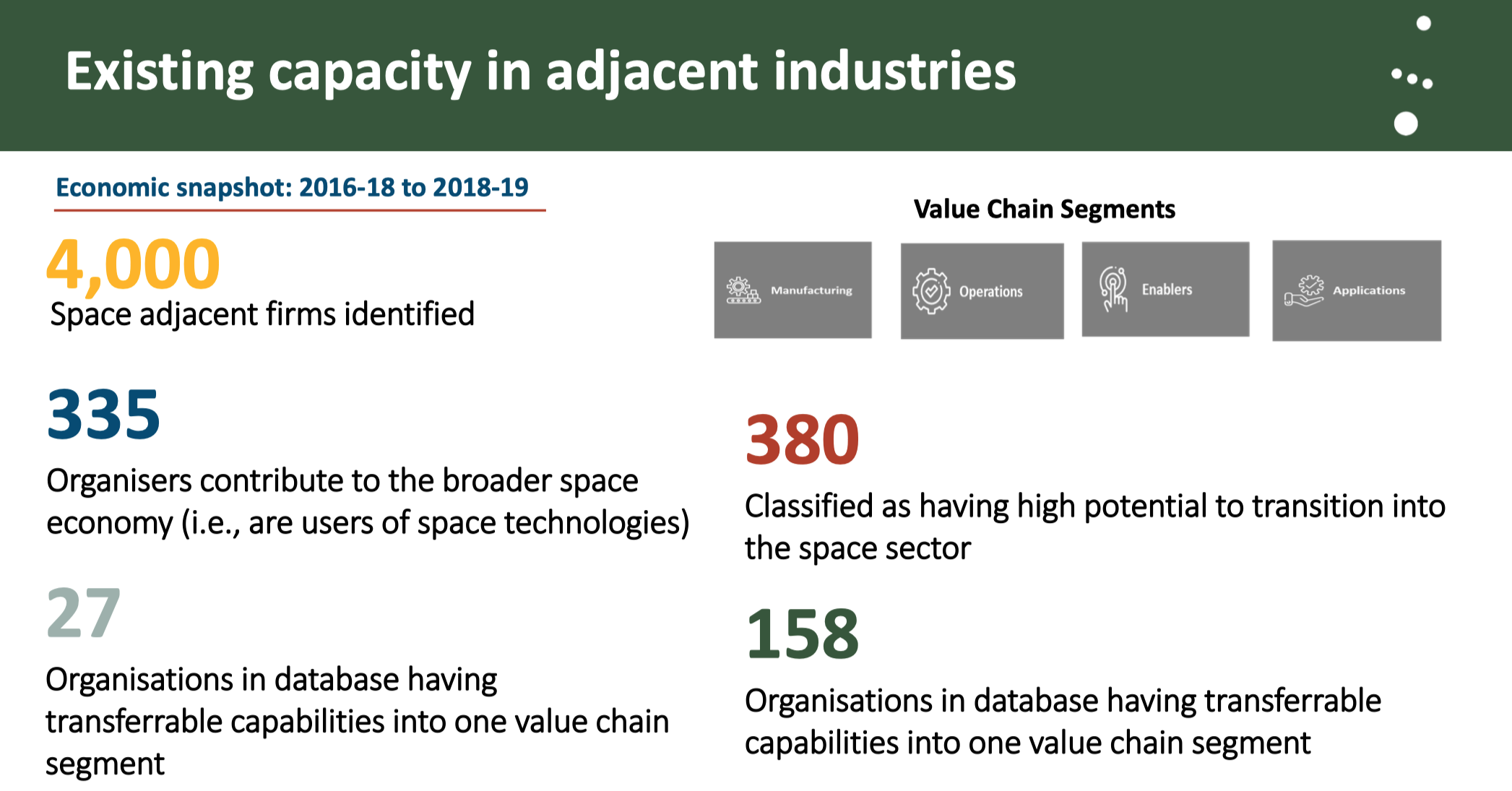

In his briefing, he presented a slide which nicely captured much of his argument:

As he put it at the seminar: There is a significant opportunity for Australia with the emergence of new space. At the delivery level, there are now a lot of options now available as a service launch, as a service, for example. Data has become a service; software has become a service. It means that government now could be a customer, and they can move with the speed of the industry. You don’t need to lock yourself in. You can change who you are using as new systems develop and emerge from new space. Sorry to the old primes here, you’re in the other column.

“But I think you probably need to actually adapt to this new space of environment as well.”

The major presentation at the seminar which provided answers to shaping a way ahead for defence with regard to the space sector was provided by Professor Tanya Monro, the Chief Defence Scientist (seen presenting at the seminar as featured photo for this article).

Notably, Defence is investing in space to improve the resilience and self-reliance of Defence’s space capabilities. Space has been recognized by the government as a Defence Sovereign Industry Capability Priority (SICP) in its own right.

She argued along the lines of van Haren that space is being disrupted by rapid technological change with the emergence of ‘New Space.’

This development has lowered the barriers to entry for all, including Australia companies.

The Government goal is to substantially increase our national space economy. And they are doing so in part by supporting a broader policy for Innovation, science and technology (IS&T) and seeing this effort as providing enablers for building a robust national space economy.

She argued that Defence space IS&T is a key Defence enabler for building a sovereign Defence space capability. “We are seeking to help create a sovereign industrial capability to provide increased space capability for Australia. To do that, we need to partner with great minds across our nation.”

She highlighted the importance of the defence innovation hub which can provided a way ahead for mission-directed research. And in the space domain by partnering with the national space sector can “deliver impacts through streamlined, agile and secure innovation pathways for our future space capabilities.”

In her presentation, she highlighted how she saw the way ahead with regard to Defence IS and To programs in the space domain area.

She noted that the “Defence Innovation Hub undertakes collaborative innovation activities with the potential to enhance Defence capabilities, including for space.” In other words, the re-set of how defence is looking to tap into Australian industry to generate greater defence capability is to be leveraged to provide for specific space capabilities, rather than the other way around.

She underscored the importance of the “Defence Rapid Prototyping Initiative (RPI) aims to increase use of innovative technologies to solve critical Defence problems with a Defence Capability Assurance Fund (CAF) to be introduced in the middle of the decade.”

In this effort, she highlighted the STaR Shots approach.

This is how the DS and T web page describes this approach:

“STaR Shots will be established to focus strategic research and drive the development of leap-ahead Defence capabilities. This strategy introduces a new concept – STaR Shots – that will concentrate strategic research efforts on a smaller number of bigger, specific and challenging problems of the scale and impact of JORN. An ambitious schedule will be set, with the aim of demonstrating leap-ahead capability within 10 years.

‘STaR Shots will be challenging, inspirational and aspirational, and will generate competitive capability best achieved through Australian investment. They will align with Defence strategic guidance, address future Force Structure priorities and be sponsored by at least one Defence 3-star leader. Crucially, they will have clearly defined transition pathways to take innovative ideas out of the laboratory and deliver real impact into the hands of the warfighter.

“STaR Shots will focus the strategic research investment program but with an increase in scale and intensity that will be supported by investment from other innovation initiatives and partner co-investment.

“The initial eight STaR Shots will be established to collectively support Defence’s ability to prevail in contested environments. Aligning with capability needs across each of the warfighting domains, they will enable Defence to get to the fight, shape how the ADF operates and generate new military effects.

“STaR Shots will be supported though investment in modelling and simulation, wargaming, prototyping, experimentation and trials. They will culminate in technology demonstrations during ADF exercises.

“The STaR Shots are deliberately ambitious and reflect Defence’s enduring commitment to invest in science and technology. As our strategic context evolves, new STaR Shots could be established to ensure that leap-ahead capabilities which align with Defence’s needs continue to be delivered.”[1]

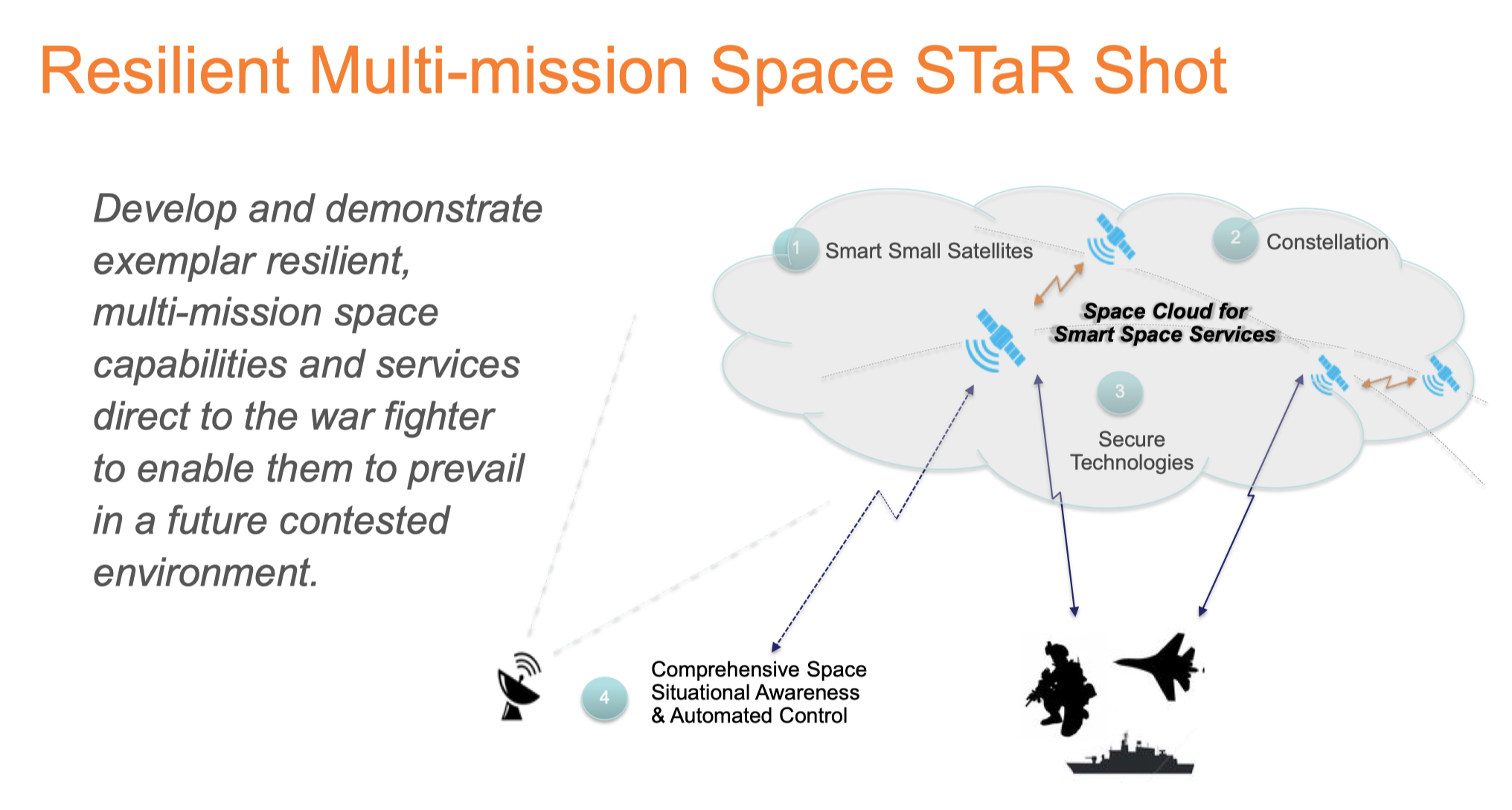

The particular space-focused Star Shot program within the overall effort is to focus on “resilient multi-mission space.” The DS and T web page identifies this effort as follows:

“Providing resilient space-based services direct to the warfighter to enable the Australian Defence Force to prevail in increasingly contested operating environments.

“Context:

“Space-based systems play a vital role in all ADF and coalition operations, wherever they occur around the world. From providing precise location information and situational understanding of the operating environment to enabling personnel and platforms to stay connected, assured access to satellite services and the freedom to operate in space are critical to the ADF’s ability to protect and defend Australia’s national interests.

“Space is now a warfighting domain. Some countries are developing anti-satellite systems and denial-of-service measures that threaten space-based capabilities. Satellites and space systems used by Defence are becoming more vulnerable as the space domain changes from a benign environment into one that is increasingly congested and contested, where adversaries seek to limit the military advantage provided by space.

“An agile and potent future force will rely on assured access to resilient and responsive space services. Seamless interoperability with coalition partners will also be necessary to support diverse missions across multiple locations around the globe.

“Opportunities:

- Advanced space-based surveillance capabilities to provide comprehensive situational awareness for superior decision-making.

- Secure and resilient communications delivered from space for a highly networked force.

- Resilient satellite services providing accurate position and timing information to enable precision effects in contested environments.

- Advanced space domain awareness and control for sovereign space operations.

- Autonomous space systems and processing capabilities to dynamically reconfigure and deliver space cloud services at speed and scale direct to the warfighter.

- Space systems hardened against anti-satellite and denial-of-service measures.”[2]

Professor Monro provided a slide in her presentation which captured some of the key elements of the space-focuses STaR shot effort:

There is also a very helpful video which was released on 3 May 2020 which highlights key elements of this effort as well.

According to the narrator of that video, the heart of the effort is to shape a small satellite network that can deliver various data to ADF warfighters operating worldwide.

The focus is to leverage the innovations in LEO systems to be able to do so. Communications, imagery, position, navigation, and timing capabilities are envisaged for the ADF user. To do this, a focus is upon developing and testing new technologies and capabilities with SmartSat CR and to work small satellite integration.

In the interview which she did with the Williams Foundation she summarized how she saw the target goals and the way ahead:

“I don’t think it’s ever reasonable to expect that Australia will have a purely sovereign space capability, but we certainly need a much more sovereign one than we have now. We’re very dependent on access to foreign space assets. I don’t think Australia will ever have a purely independent sovereign space capability.

“And I don’t think we need one, but I do think we need a much more sovereign space capability than we have now. We need to know that when push comes a shove, we can rely on space assets to support our nation and its protection of its own interests, that our ADF can rely on having access to space when needed.

“We need to build very significant Australian sovereign industry capability to support that. And I think that that helps us be a better international partner. What we absolutely must do is work with our allies to make really clear where Australia has niche advantage, so that we can create opportunities for our companies to export to the world in those areas and that we can buy other complimentary areas of capability and technology from allies.

“For me, a future Australian sovereign space capability means assured access to the things we need when we need them under pressure. But it doesn’t mean every space asset that we use is sovereign. Defence has a range of innovation programs that are designed to help foster, support, and invest in new space technologies and capabilities.

“This includes the Defence Innovation Hub, which can accept great ideas from industry and really pull them up the technology readiness levels to the point where they could be demonstrated and tested in a defence context and then pulled through to acquisition programs.

“And it’s really exciting to see how many of these projects are now maturing to the point where they are serious acquisition prospects, and indeed a number are pulling through into capability. We also have things like The Next Generation Technologies Fund which can take earlier staged ideas to get them to the point where we could put them through that innovation pipeline.

“There are increasingly a range of different ways that companies, big and small can interact with defence. I think what we’re increasingly focusing on over the next couple of years is getting engaged with industry earlier. Hearing your good ideas and working out how we can reduce the barriers for you to be able to develop new technologies in a defence context.”

[1] https://www.dst.defence.gov.au/strategy/defence-science-and-technology-strategy-2030/science-technology-and-research-star-shots.

[2] https://www.dst.defence.gov.au/strategy/star-shots/resilient-multi-mission-space.