On June 21, 2021, the U.S. Sixth Fleet announced the coming of Sea Breeze 21.

U.S. Sixth Fleet formally announces participation in the upcoming annually held Exercise Sea Breeze 2021 (SB21) cohosted with the Ukrainian Navy, June 21, 2021.

The exercise is taking place from June 28 to July 10 in the Black Sea region and will focus on multiple warfare areas including amphibious warfare, land maneuver warfare, diving operations, maritime interdiction operations, air defense, special operations integration, anti-submarine warfare, and search and rescue operations.

This year’s iteration has the largest number of participating nations in the exercise’s history with 32 countries from six continents providing 5,000 troops, 32 ships, 40 aircraft, and 18 special operations and dive teams scheduled to participate.

“The United States is proud to partner with Ukraine in co-hosting the multinational maritime exercise Sea Breeze, which will help enhance interoperability and capabilities among participating nations,” said Chargé d’affaires Kristina Kvien, U.S. Embassy in Ukraine. “We are committed to maintaining the safety and security of the Black Sea.”

Beginning in 1997, Exercise Sea Breeze brings most Black Sea nations and NATO Allies and partners together to train and operate with NATO members in the pursuit of building increased capability.

SB21 provides the opportunity for personnel of participating nations to engage in realistic maritime training to build experience and teamwork and strengthen our interoperability as we work toward mutual goals.

Ukraine and U.S. are cohosting the exercise in the Black Sea with participation and support coming from 32 countries in total: Albania, Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, France, Georgia, Greece, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Morocco, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Senegal, Spain, South Korea, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and the United States.

Black Sea nations, in concert with NATO Allies and partners, improve their ability to conduct the full range of naval and land operations by participating in exercises like Sea Breeze 2021.

Exercise Sea Breeze 2021 is an annual multinational maritime exercise, involving sea, land, and air components, and is co-hosted by the United States and Ukraine to enhance interoperability and capability among participating forces in the Black Sea region.

U.S. Naval Forces Europe/Africa/U.S. Sixth Fleet, headquartered in Naples, Italy, conducts the full spectrum of joint and naval operations, often in concert with joint, allied, and interagency partners, in order to advance U.S. national interests and security and stability in Europe and Africa.

This exercise will unfold in a challenging geo-political region.

The broad background with regard to operating in the region was laid out in a 2014 article by Ed Timperlake.

The Black Sea, Area is 168,496 sq. miles ringed by the following countries:

- Bulgaria, Size of Tennessee with 6.9 million people

- Romania, slightly larger than Oregon with almost 22 Million People

- Ukraine, slightly smaller than Texas with 44 million people

- Russia largest country in the world (1.8 times size of US) 142 Million people

- Georgia (Remember them from 2008?), slightly smaller than South Carolina with population of 4.9 Million

- Turkey, larger than Texas with a population of 81 million

(Compiled information with CIA fact book population estimates 2014)

The Black Sea as an enclosed body of water and narrow passages of sea can rapidly become a “Beaten Zone” for surface ships.

Such a constrained operating area reminds one of the importance of no platform fights alone; no ship should be sent along without a clear understanding of the threats it might face, and notably, the specific character of threats in constrained operating areas.

There is a blunt direct use of words in ground combat that can signify the possibility of a military disaster, it is up to commanders to determine through their actions that the words mean a battle field defeat or a challenge to be fought through on the way to a victory. The words are “The Beaten Zone” and it is defined in the US military dictionary as “the area on the ground upon which the cone of fire falls.” From Infantry Squad leaders up the Chain-of-Command all engaged must never allow the enemy to establish a “beaten zone” and if trapped in one rapid action is required to evacuate the area while trying to destroy the enemies weapons it is the difference between life and death.

It is a ground term but can also be employed at sea because of the increasing accuracy and lethality of modern weapons.

There are several high traffic strategic waterways and confined seas around the globe that an enemy can create a “beaten zone” for surface ships.

Ships going through the Dardanelles into the Black Sea give us a lesson from history on this very point of what a Beaten Zone can look like for the surface navy.

And with Russia having seized the Crimea, and a significant part of Georgia, and now building up Eastern Med capabilities, as well as operating ships in the Caspian as mobile missile bases, the Russians are enhancing the challenges of operating in the region as well.

Notably, the Russians recently highlighted the growing threat envelope by going after a British warship operating in international waters in the region. And the Russians certainly did not step back from their actions. In the wake of their attack on HMS Defender, this is what the London Times reported the Russians did next.

Russian fighter jets, warships and submarines launched military exercises in the Mediterranean today while tracking Britain’s aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth.

The drills came days after Moscow said that one of its patrol ships had fired warning shots and a jet dropped bombs in the path of the Royal Navy’s HMS Defender as it sailed about 12 miles (19km) off the coast of Crimea, the Ukrainian peninsula annexed by Russia.

Sergei Ryabkov, the deputy foreign minister, warned today that Russia could bomb British ships in the Black Sea if there were more such “provocative” incidents. “We can appeal to common sense, demand respect for international law, and if that doesn’t work, we can bomb,” he said.

MiG-31K fighters were being deployed in Syria for the first time in the war games in the Mediterranean, and Tu-22M3 bombers for the second time.

MiG-31K aircraft are capable of carrying the Kinzhal hypersonic missile, one of the new-era Russia weapons lauded by President Putin. The exercises also featured the Moskva guided missile cruiser, the Admiral Essen and Admiral Makarov frigates, and two submarines.

A very good sense of how the military geography of combat is changing in the entire Mediterranean region has been provided by a retired U.S. Navy intelligence analyst.

According to J.E. Dyer in an article published on June 26, 2021: Russia has logged some major firsts in their Eastern Med exercise underway.

On Friday, after the series of untoward events in the Black Sea over the past week, Russia began a maritime exercise in the Eastern Mediterranean featuring – according to Russian reporting – “several” warships, two submarines, Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers, and MiG-31BM Foxhound fighters said (by Russia) to be armed with Kinzhal hypersonic air-launched ballistic missiles, with a range of up to 1,000 nautical miles (1,250 statute miles) ….

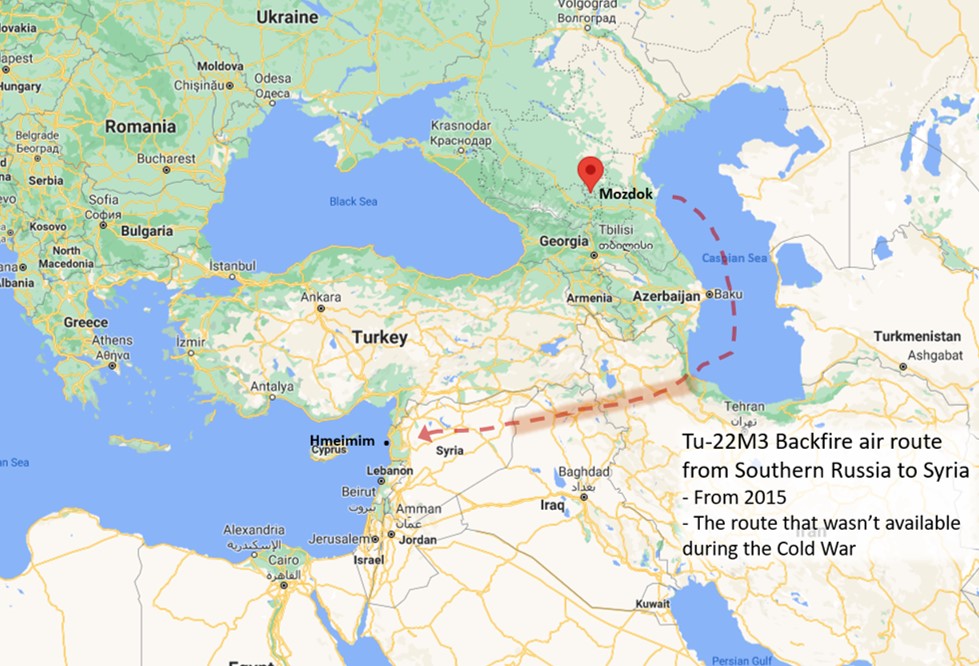

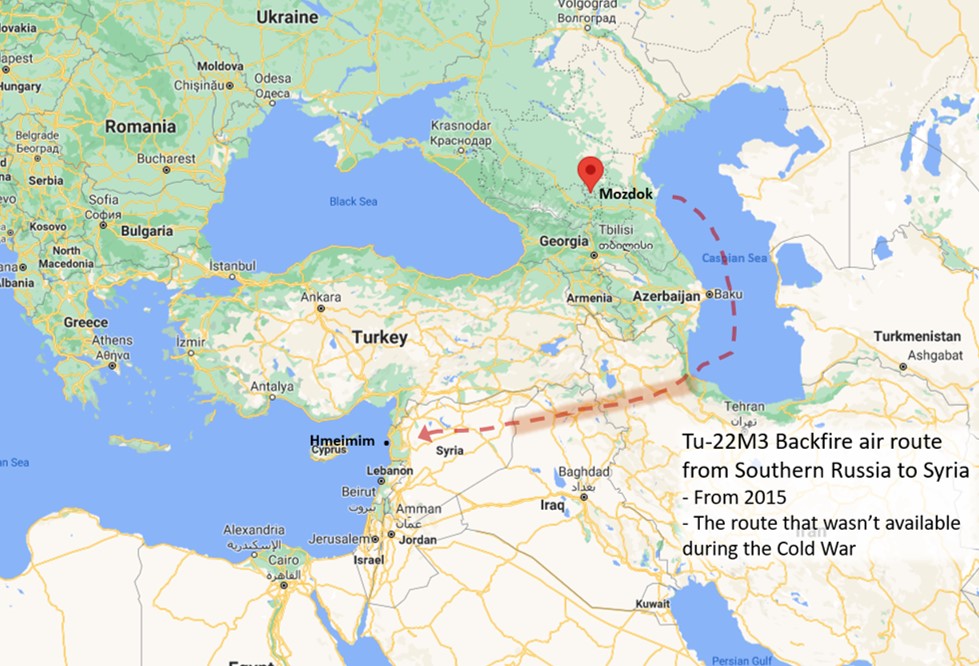

The base of operations for the aircraft is Hmeimim airfield on Syria’s coast, from which Russia has been operating fixed-wing combat aircraft since 2015. The reason is simple. Russia can now put combat aircraft, including heavy bombers, in Syria and hold the Eastern Med at risk without having to run a NATO gauntlet to get there. That’s something the former Soviet Union could never do during the Cold War…

Now, for the first time ever, Russia has heavy bombers menacing NATO out of Syria, along with modified fighters armed with one of her newest nuclear-capable missiles, all without prior vulnerability to NATO interdiction on the route to the theater.

Russia lost Ukraine in the breakup in 1991-92, and has made only partial progress regaining control of territory there. Yugoslavia is gone. Several former-Yugoslav nations, along with Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania, are NATO allies today. The path through Iran and Iraq depends on Russian relations with Iran and Iraq. But the latter path, the one Russia never had before, is beyond the ready combat reach of NATO. We’re in a new century now.

For a look at the history of national participation in the Sea Breeze exercises, see the following:

210621-N-NO901-0001.JPG

For a look at J.E. Dyer’s illustration of the new Russian template for operations, see the following:

The Eastern route to Syria, well east of NATO’s organized alliance defenses. Russia has deployed her air force assets into Syria by this route since 2015. The first Tu-22M3 deployment to a Syrian base from the East began in May 2021, although Backfires used this route earlier to operate in Syria from the Russia bomber base at Mozdok. The shaded area indicates where Russian aircraft must pass through Iranian and Iraqi air space. They have had permission for that from Baghdad since late 2015. Google map; J.E. Dyer’s annotation