By Kenneth Maxwell

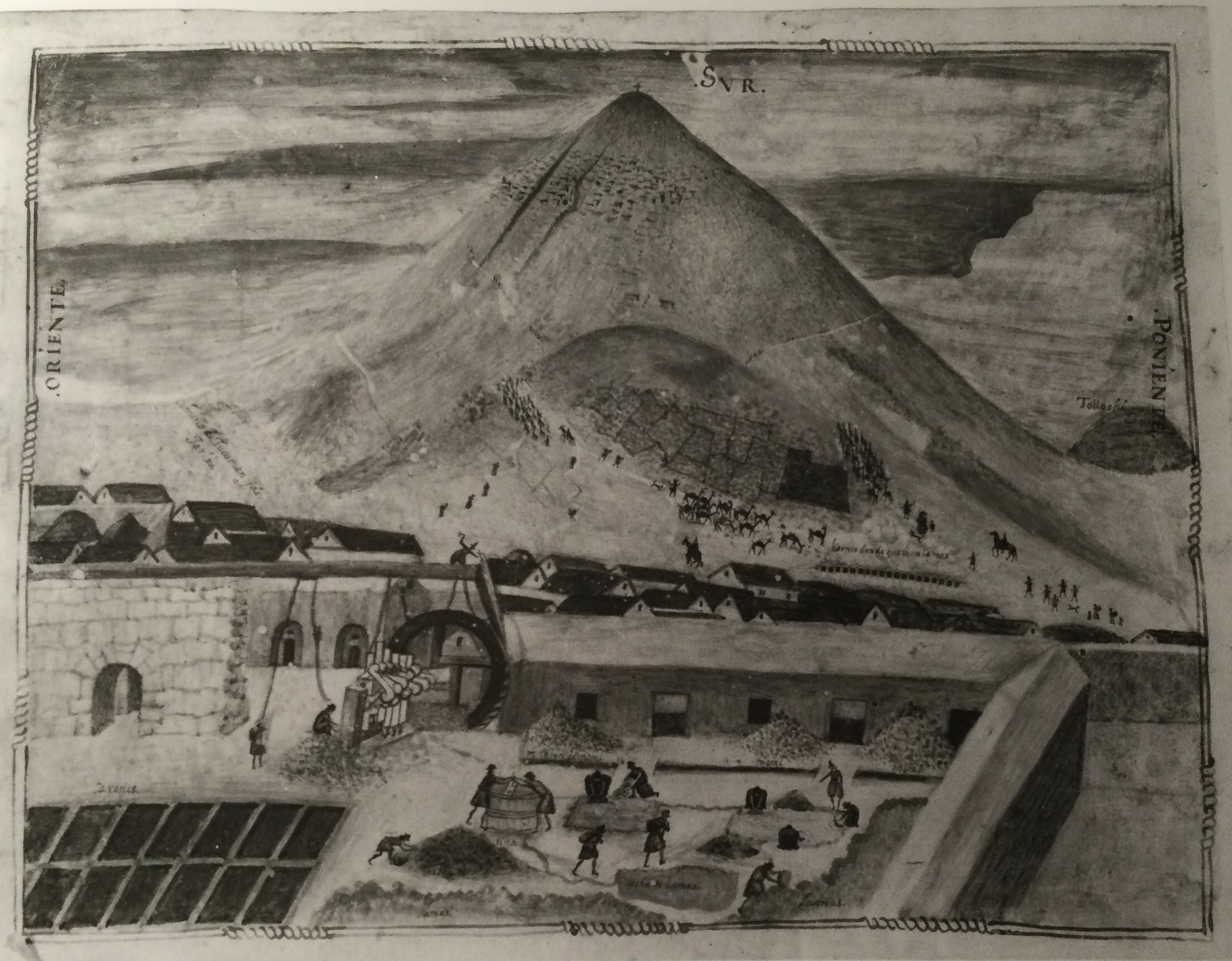

A decade after the Spanish Conquistadores toppled the Inca Empire (1532-34), an indigenous Andean prospector, Diego Gualpa, in 1545, stumbled onto the richest silver deposit in the world on a high mountain of 4,800 meters (15,750 feet) in the eastern cordillera of the Bolivian Andes.

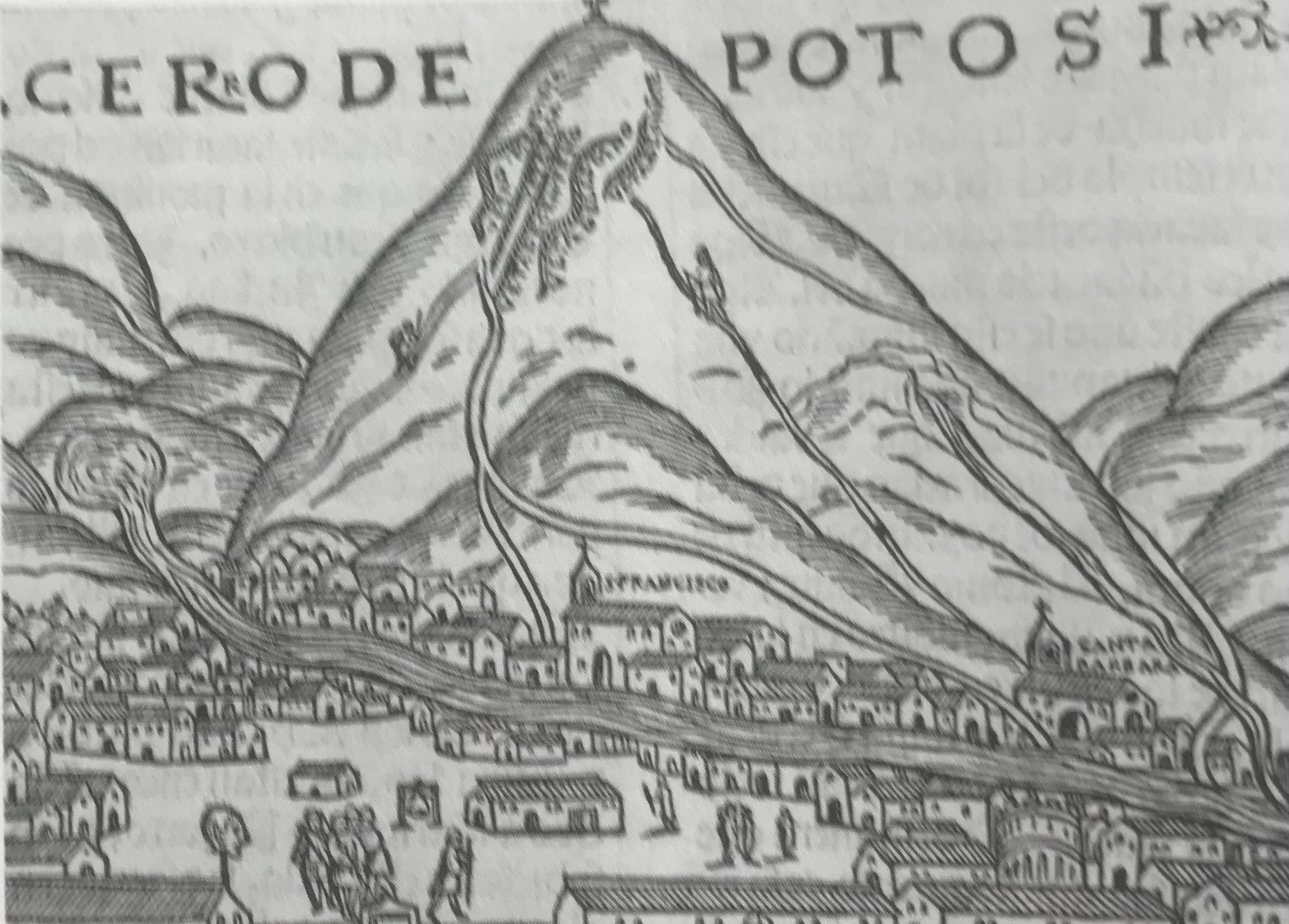

Here in the shadow of what the Spaniards called the “Cerro Rico” (“Rich Mountain”) at 4,000 meters (13,200 feet) a mining boom town quickly developed. By the end of the sixteenth century, it had become one of the largest and the highest cities in the world, and in 1561, Philip ll of Spain, decreed that it should be known as the “Villa Imperial de Potosí.”

Peru already had a reputation as the source of unfathomable treasures thanks to the ransom in gold and silver gathered for the Inca emperor Atahualpa seized by the conquistador Francisco Pizarro in an ambush at Cajamarca which had amounted to a million pesos of fine gold and silver when melted down. A similar amount was seized from the Inca treasury of Cuzco. Pizzaro ordered Atahualpa executed by garrote in July 1533. When the Inca treasure arrived in Seville in 1534 it was enough precious metal to upset the money markets in Europe and the Mediterranean.

16th Century Potosi and Global Trade

During the sixteenth century the population of Potosi grew to over 200,000 and its silver mine became the source of 60% of the world’s silver. Between 1545 and 1810 Potosi’s silver contributed nearly 20% of all known silver produced in the world across 265 years. It was at the core of the Spanish Empire’s great wealth. The Habsburg Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, called Potosi “the Treasury of the World.”

He was right. Potosi became the engine of an international network which ended Eurasia’s bullion famine after 1550 and provided the silver flows that reached westwards across the Atlantic Ocean from South America via the isthmus of Panama to Spain and Europe, and to the east from Seville in Spain and Lisbon in Portugal to the Ottoman and Safavid Empires and to Mughal India and to China under the Ming and Qing dynasties.

After 1565 silver from the Americas also crossed the Pacific Ocean to the Spanish entrepôt at Manila in the Philippines (named after King Philip ll of Spain) and on from Manila by Chinese junks to the Fujian in China where the port of Quanzhou was one of the world’s busiest shipbuilding and commercial centers of overseas and coastal trade with more than 100,000 Arab traders living in the area.

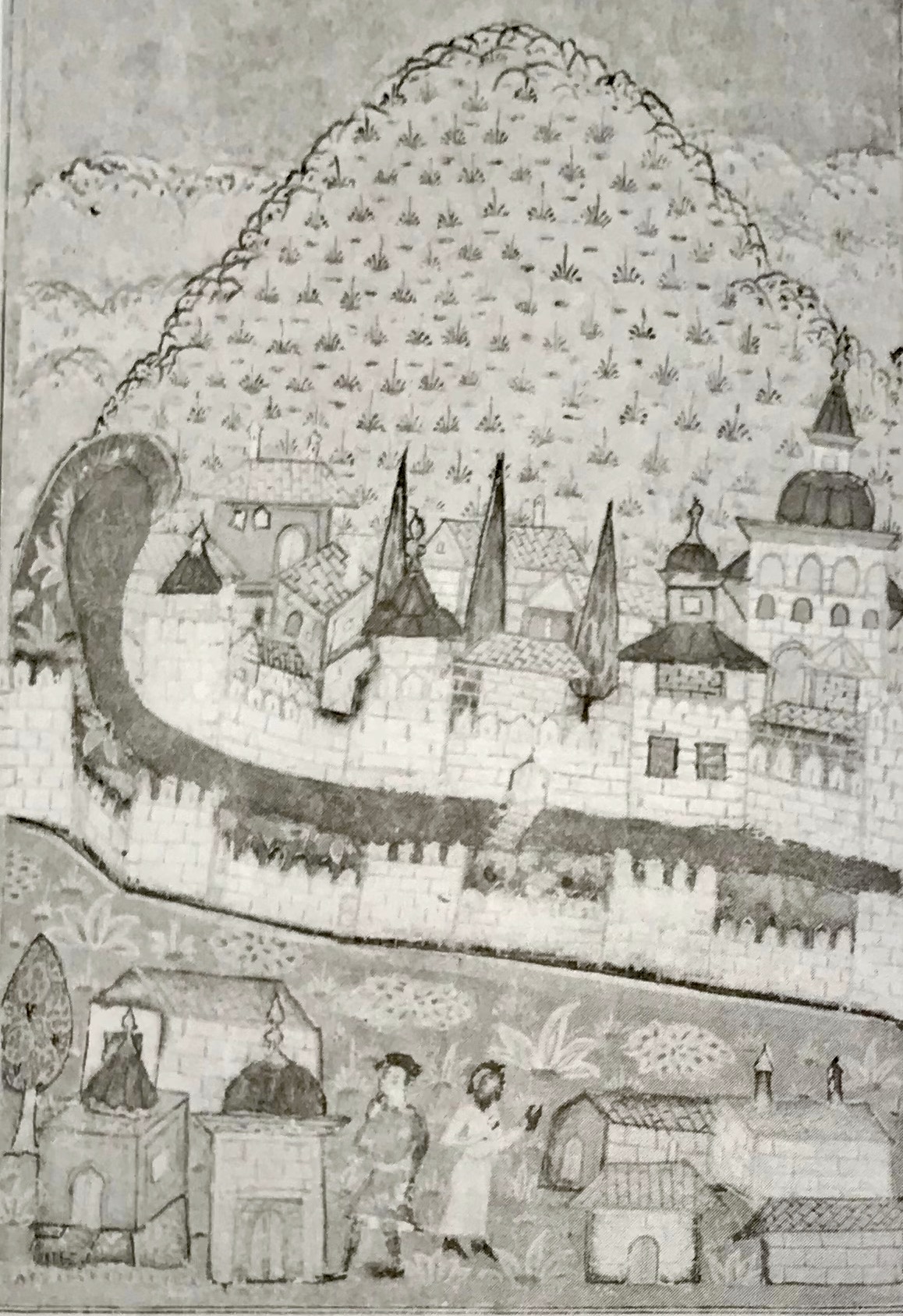

From the 1550’s Potosi was at the center of the first explosive development of global intercontinental exchange creating the first true globalized economic and trading network. In effect it created the first global currency of exchange, the “pieces of eight” each with the mark “P” for the Potosi Mint established by the Viceroy of Peru (1569-1581), Francisco Alvares de Toledo, in 1574. The most famous image of the “Cerro Rico” came from the much-copied 1553 woodcut illustration published in the “Crônica del Peru” by Pedro de Cieza de Leon. By 1580 an Ottoman version of the “Cerro Rico” of Potosi was depicted in the Tarih-l Hind-l Garbi. In 1602 the Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci and his assistant Li Zhizou marked the “Potosi Mountain” (Bei Du Xi Shan) on their world map for Wanli, China’s Emperor.

Producing Silver

The great silver (and tin veins) of Bolivia’s Eastern Cordillera are the richest of both metals on the world. The “red mountain” is still producing silver, tin, zinc, lead, and other metals. The silver rich veins of the “Cerro Rico” are about a meter wide on average and the vines dive steeply into the mountain from the surface. Within decades the miners reached the water table at 400 to 500 meters depth.

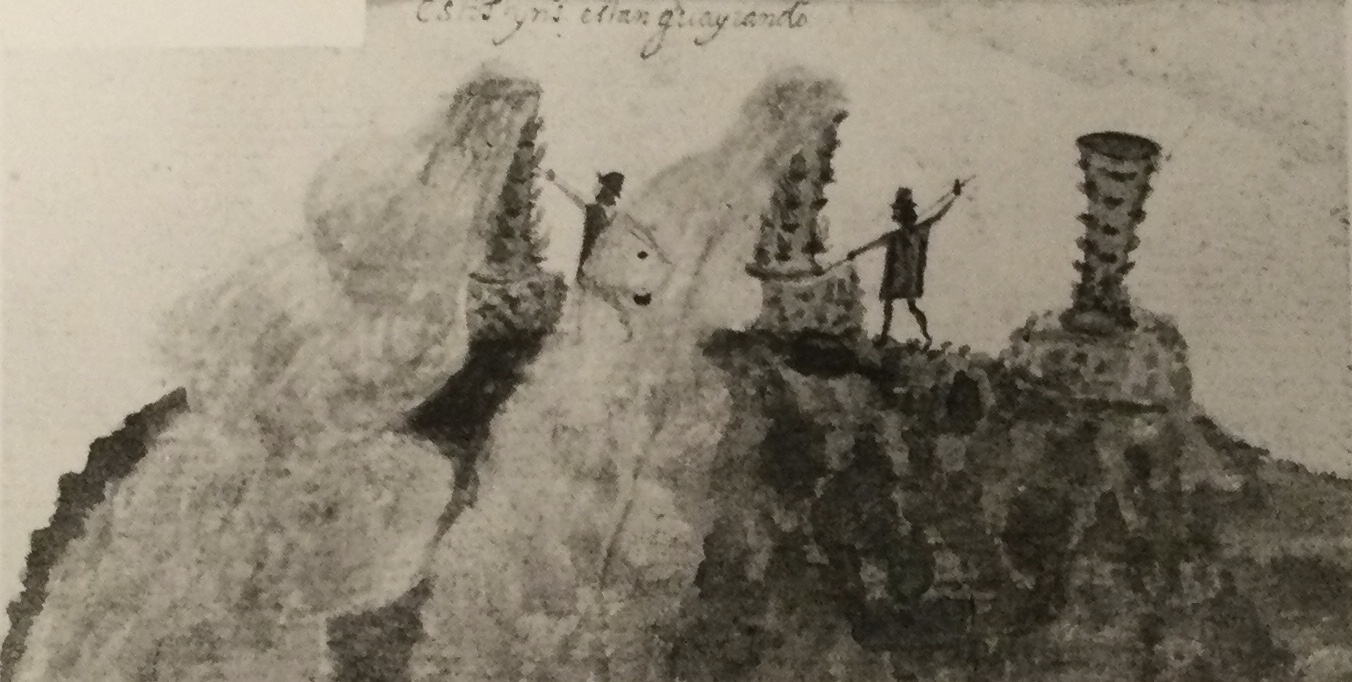

The rich surface silver ores at Potosí were processed initially by smelting. Using stamp mills, powered by mules or water wheels, the silver ore was crushed to gravel then smelted in blast furnaces with lead and lead oxide. 6000 such furnaces (guayra), set on pedestals to capture the wind, covered the hills around Potosi during the early years burning wood, charcoals, and llama dung. The air blast was provided by sheep or goat skin bellows.

The water came from the warm mineral springs on the road to Oruro, where the “Ojo del Inca” (the Inca’s Baths) at Tarapaya provided the reagents to the dozens of early refineries. The massive salt beds of the Salar de Uyuni, the World’s largest salt flat, was several days walk away.

The silver-gold alloy produced in the early sixteenth century was first shifted to cupulation furnaces where the porous bone-ash-lined interior absorbed the oxidized lead. The pure silver and gold alloy remaining at the bottom of the couple where it was separated by a nitric acid method which had been introduced from Germany, then also part of the vast Habsburg domains.

The rapid introduction of the most modern technology was a characteristic of these early years of European colonial activity in the Americas. The dramatic rise in Spanish American silver production in the 1570’s was the result of the adoption at Potosi of the “patio” process of amalgamation of silver ores with mercury which produced a quadrupling of silver export from Peru in the ten years between 1576-1585.

The introduction of the “patio” method in Mexico about 1554 and is attributed to a merchant from Sevilla, Bartolome de Medina, who developed mercury amalgamation. The great advantage of the amalgamation over smelting was that it made the exploitation of lower grade silver ores profitable and greatly extended the range that could be worked, and salt mixed with mercury was used to extract fine grains from silver from what had before been worthless host rock.

The Silver Production Process

The ore for amalgamation was crushed to a fine powder and mixed with water and mercury, salt, and impure copper sulfate. The muddy composite was spread out over a stone paved courtyard (the “patio” hence the name “patio” process). Here it was agitated by a team of mules, and then heaped into piles where it stood for some weeks while the silver ore was separated chemically and amalgamated with mercury.

The mud was then washed away into troughs or vats (tingas) and the silver amalgam put into canvas bags, any free mercury filtering out. Pressed into bars the residual amalgam was then placed into small conical furnaces where the mercury was vaporized and recovered, though one quarter of the mercury was lost in the processing of silver ore. The silver was then taken to the office assay office for recasting and stamping with weight, fineness, and the royal coat of arms.

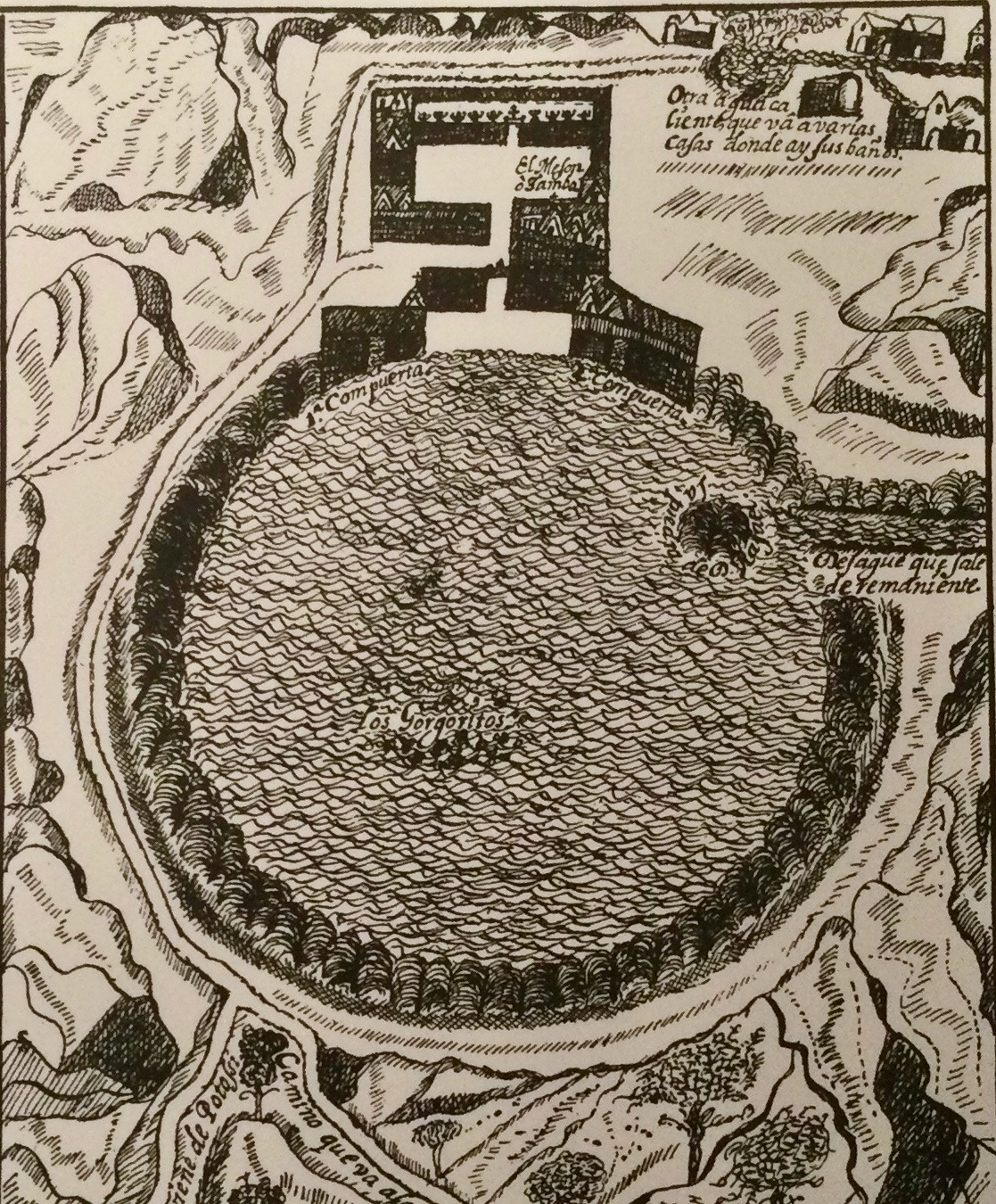

The repossessing plants were called “haciendas de minas” and were substantial establishments containing the stamp mill and incorporating the residence of the mine owner, his houses of workers and their families, as well as a chapel, stables for mules and horses, machinery sheds, and store houses. The buildings were constructed near streams whenever possible because water was essential to operate the machinery of the mill.

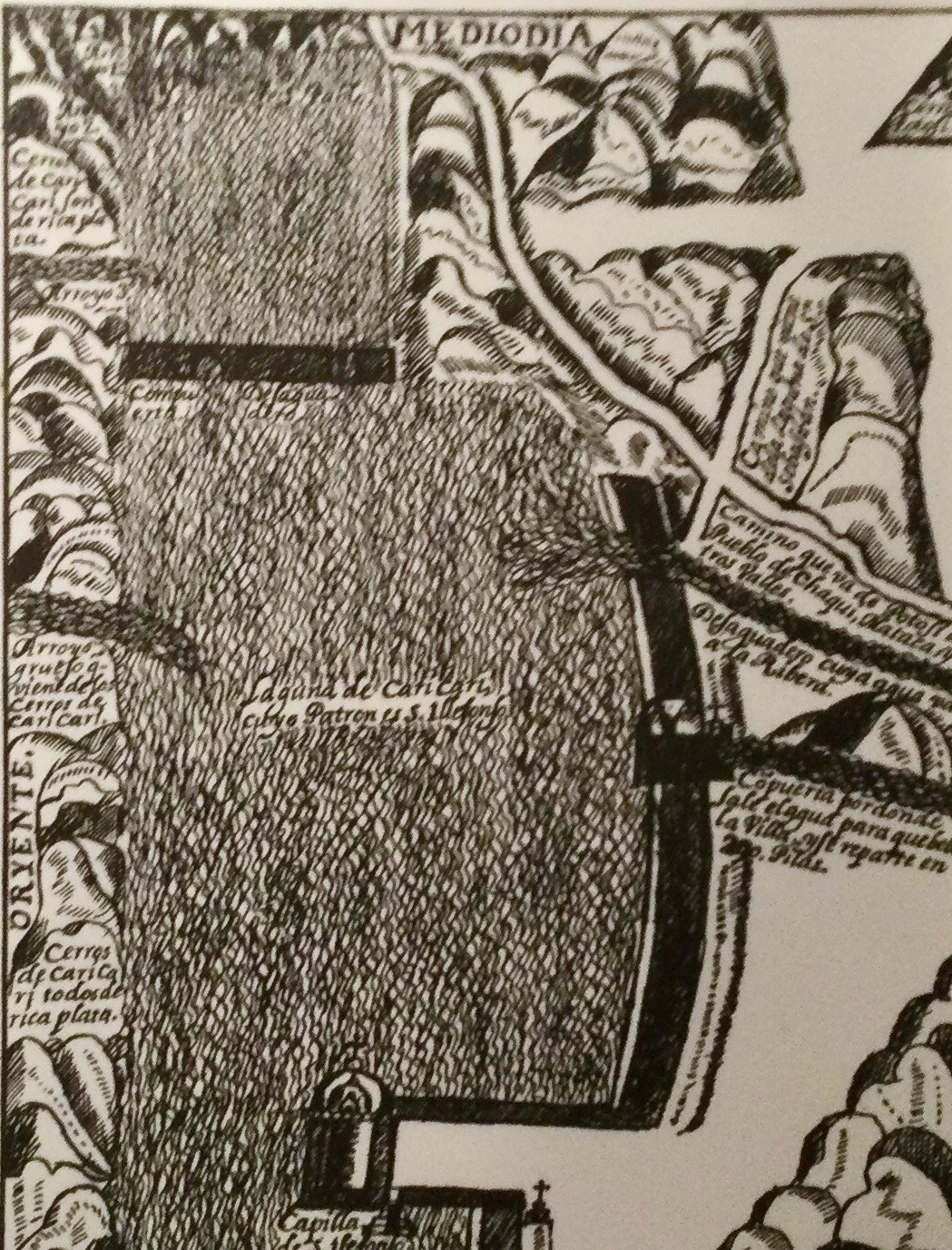

Since rain was unpredictable at Potosi, the Spanish viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Toledo decided to construct in the nearby Kari mountain full scale reservoirs linked by canals and aqueducts to Potosí, a huge public works projects completed by thousands of Andean indigenous draftees. At Potosi there were 120 processing mills in 1658. The mills were complex and expensive. In 1572 some had machinery 18 feet in diameter and a foot wide connected to an axle to lift and drop six stamp hammers. Others had a 24-foot mill wheel and eight to twelve stamp hammers.

Mercury was essential to the processing of silver ore and was imported from the Almaden mines in La Mancha in Spain. The heavy metal liquid metal was packed in sheepskins and shipped to the Americas where the mercury was transported over the isthmus of Panama and shipped down the Pacific coast, taken by mules and llamas to Arica and then overland to Potosi. In 1563 this situation was transformed when a rich mercury mine was discovered at Huancavelica in central Peru.

Spain and Peru

A city was established there by the fifth viceroy of Peru, Francisco Alvarez de Toledo, in 1572, who called the new settlement “Vila Rica de Oropesa” after his title and his hometown in Castile. But the name Huancavelica (a corruption of the Quechua name for the site which meant “stone idol”) stuck. It is one of the poorest cities in Peru today with a majority population composed of indigenous peoples. The valleys are 1,950 meters above sea level. The snow capped peaks that surround Huancavelica stand at 5,000 meters high. It is a cold and barren landscape.

The Spanish Crown appropriated the mines in 1570 and operated them until Peru’s independence in 1821. Huancavelica became the “greatest jewel in the Crown” and mercury became the basis on which the tax on precious metals, the “quinto,” was levied. Fernandes de Velasco, a Spaniard, who had arrived in Peru from Mexico in 1572, was able to modify the amalgamation process so that the Huancavelica mercury might be applied to the Potosi silver ores.

The consequence in the words of the viceroy Toledo was to consummate “the greatest marriage in the world” between the mountains of Huancavelica and Potosi. Between 1576 and 1600 two-thirds of all mercury consumed in Spanish America came from the Peruvian mine. Work at the Huancavelica mercury mine for much of the sixteenth century was above ground using open cast techniques.

After 1597 it became necessary to mine underground and the deterioration of working conditions was rapid. Galleries were haphazard, airless, and full of dust, and few miners escaped permanent crippling from mercury poisoning. Labor in the Peruvian mines was almost exclusively provided by the indigenous population.

The Viceroy Francisco Álvares de Toledo who had fought the Ottoman Turks in Tunis and opposed the rise of Protestantism in Germany, and was a close to the court of the (now retired) emperor Charles V, had been sent to Peru by Philip ll. He was the fifth Spanish viceroy and he remained in Peru eleven years and five months and traveled in tours of inspection over five years and 8000 kilometers over its territory.

He was the only viceroy to visit Potosi. He ended the chaotic situation of the first decades of Spanish dominion. He overthrew the neo-Inca state at Vilacabamba and defeated the last neo-Inca ruler, Tupac Amaru (1542-1572), and executed him in Cuzco. He forcibly resettled the Andean population in permanent settlements (reducciones). He established a Pacific fleet based in Callao (Armada del Mer del Sul) and in 1570 he established the Inquisition in Peru.

Above all the viceroy Toledo recast the “Mita” which was an Inca system of obligations in order to provide one-seventh of the able-bodied male indigenous Quechua and Aymara farmers and pastoralists of the highlands for various tasks in the Spanish sector of the colonial economy. Sixteen Andean provinces were designated to provide a labor pool for Potosi at any given time. 13,000 were obligated to work in Potosi where they would be distributed to mines, stamp mills, or to various tasks in the city.

At the Santa Barbara mine in Huancavelica (opened in 1564) 3,280 Mita workers by 1577 were drafted in rotation to labor in the deadly mercury mine. Andean caciques and kurakas (local indigenous head men) served as middlemen, fulfilling the labor quotas, responsible to Spanish magistrates (capitates de la Mita.) These forced labor drafts were only outlawed in 1812 and were declared over by Simon Bolivar in 1825.

The viceroy Toledo also established the mint in Potosi in 1574. The smelting of coin material and the cutting, preparing the coin blanks for stamping was carried out by indigenous draftees and enslaved Africans at the Casa de la Moneda. In 1592, 444,000 lbs. or 200,00 kgs of pure silver was “reported” as processed in Potosi. The annual production being about 300,000 lbs. or 136.000 kgs through the 1640s.

The mint mixed private and public interests. The crown officials included the treasurer, assayer, smelter, master of weights and measures, and the bailiff. These officials were Spanish born and were required to sign an oath to behave honestly and they were bonded by leading Potosi households. The hardest tasks – smelting coin metal, cutting and preparing coin blanks for stamping – was carried out by drafted Andeans and enslaved Africans.

The silver bars were brought to the mint from the Royal treasury office next door where the Royal Fifth was paid. The coins were made by hand. These were the famous silver “prices of eight” worth eight reales, stamped with the coat of arms of the Habsburg Monarchy and a Greek cross with Lions and Castles, and with the “P” for Potosi.

The geographical mobility brought about by the massive impute of cheap forced indigenous labor in these transactions is hard to imagine much less to quantify. But they were critical to the production of silver.

It took two months for the 2,000 indigenous people required for the labor draft of Chicuito, on the southwest shore of Lake Titicaca, together with their families, each with ten llamas, to travel the 300 miles to Potosi. Together they composed a small town (7000 people and 30,000 animals) in transit.

The contingent from Chucuito was only part of the 40,000 indigenous peoples encamped at the foot of the Serro Rico or travelling to and from the high plateau to meet their Labor obligations. Luis de Campoche claimed that the roads of Peru were so covered with people that it seemed that the whole kingdom was on the move. The conde de Tepa claimed that without their labor the “America would sink into total ruin.”

Potosi Mining Methods

At Potosi mining methods were primitive. Adits were dug into the side of the mountain in order to access the veins of silver ore. Conditions underground were harsh. The silver ore was loosened by hammers, picks and crowbars, and carried in hide sacks, weighing 100 pounds a time, to the surface. Access to the mines (Potosi reached a depth of 750 feet by 1600) was by ladders of twisted rawhide with wooden rungs, wide enough to permit two files of workers to climb up and down at the same time.

Elsewhere crude noticed pine logs reaching up to 400 feet from the lower levels were used. Flooding was a constant problem, only partly overcome by such crude methods as hoisting out the water in leather buckets and the use of primitive pumps. In Potosi miners might remain underground for the entire work week. Silicosis and pneumonia were common in underground workers. The toll of death, disease and flight, meant that not all the miners at Potosi were Mitayos. By 1600 half the mine workers were indigenous self-hired workers receiving wages.

The silver produced in Potosi was carried on the backs of llamas and mules to Pacific coast from whence it was shipped from Arica to the isthmus of Panama where mule trains carried the silver overland to the Caribbean port of Nombre de Dios.

The Trade Routes

The sea connection between Panama and the Peruvian coast was especially difficult. Prevailing southerly winds made it almost impossible to reach Peru from Panama except in January and February. The return voyage was easy and could usually be accomplished in less than a month. Cargoes for Lima were unloaded at Calloa and carried inland by mules or in heavy carts.

By the 1530s some thirty ships a year were involved in the Panama to Callao trade; at the end of the sixteenth century the number ranged from fifty to sixty. Ships for the Pacific coastal trade were built in Nicaragua, Guatemala, or in Mexico, and could be as large as 300 tones. Silver was also carried via the Rio de la Plata (the “silver river”) following the reestablishment of Buenos Aires in 1580. African Slaves were also sent by this route to Potosí until 1622 when the Spanish crown insisted that all African slaves for the Spanish American pacific coast territories be sent via Panama (though the clandestine trade via Buenos Aires continued).

The silver of Potosi thus stimulated the formation of a sophisticated regional and global trading network. Iron from northern Spain was essential to mining. Spain had some of Europe’s richest iron deposits and Basque ironmongers became essential to Potosi. Hardware had to be imported from Spain: Ironware, nails, horseshoes, machetes, pickaxes, hinges, locks. These revolutionized Andean mining as mine workers were now able to chip away hard rock. The “Imperial Villa of Potosi” was on a barren plateau devoid of everything needed for life and work. All had to be brought from afar.

The growth of Potosi stimulated the regional economy. Luis Capoche writing in 1585 observed that “nothing in the way of food can be produced in Potosi or the surrounding areas except some potatoes (which grow like truffles) and green barley, which does not form grain because the cold is continuous…”

This was an exaggeration. Like so much written about Potosi. Yet it is certainly the case that the Spaniards needed to overcome formidable obstacle in ordered to successfully exploit the mineral resources of the high Andes, overcoming obstacles of labor supply, distance, transportation, capital, and technical expertise. The demands of the mining community for supplies, food and labor were so great that it opened up a whole spectrum of profitable opportunities and provoked a series of regional and international repercussions.

By 1620 the population of Potosi reached between 100,000 and 120,000 people, making it larger than Seville or Lisbon, and half the size of the greatest cities in Europe. Potosi acted as a magnet for produce and manufactured goods from all over South America and beyond.

Agricultural and pastoral activities were stimulated on both sides of the Andes. Coca leaves were obtained from the steaming valleys of the eastern Andes and was consumed in great qualities by mine workers during their weeklong twelve hour per day shifts in the mines. Mate tea, held to be of medicinal value, was brought to Potosi from Paraguay.

African slaves from Angola were imported clandestinely via Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires. Mules and cattle were raised around Cordoba and Tecuman province (in present day Argentina, literally “the land of silver”). Grapes and dried fish were sent from the Pacific coast. For the richest citizens, fresh fish arrived from the Pacific packed in ice. Textiles came from Cuzco or were imported from Europe via the official route through Panama, or by the clandestine route though Brazil.

No less vital were the bulky raw materials required by the silver mining and processing establishments- iron, salt, lead and litharge, copper sulfate and mercury. A network of communications thus developed which joined the mining centers to the colonial capital, the seaports, and their regional supply zones.

In the viceroyalty of Peru, Huancavelica and Potosi, were over 1000 miles apart. Mercury from Huancavelica was carried by llama and mule to the east at Chincha, shipped by Galleons to Arequipa, and then transported overland to Potosi. From Lima, Arequipa, and Huancavelica, routes linked Cuzco and Potosi, crossed the Andes, Chaco, and Pampas to Buenos Aires. To service their trade routes, daft animals were required in vast numbers, llamas, and oxen, as well as specialized muleteers.

The rise of silver production in Potosí also transformed the shipping in the Spanish Atlantic system. By 1531 silver imports into Seville passed gold by weight and by 1561 silver imports surpassed gold by value. Although precious metals composed the highest percentage of the value of cargoes from the New World. products such as cochineal, silk, tobacco, indigo, and hides became increasing important components of Spanish American trade with Europe.

In return came a diversity of European goods: wines, almost all from the Seville region, Andalucian olive oil and raisins, as well as the cloth of Castile and Flanders, paper and books. In addition, there was a demand for Spanish iron which was shipped in bulk and worked up in Mexico and Peru, above all was mercury which was indispensable to extracting silver. The 1597 fleet for New Spain for example carried 2 2,050 casks of wine, 14,120 arrobas of olive oil,14,101 quintiles of bulk iron. In 1600 the fleet carried 3,393 quintiles of mercury.

The rise of bulky commodity exchange demanded larger ships and the value of the cargoes carried demanded greater security. After 1559 there was a tacit understanding between France and Spain that beyond a line west of the Canaries and south of the Tropic of Cancer the European powers were not held to the standards of conduct that governed their relations in Europe. As the saying went: “No peace beyond the line.” The Spaniards in response instituted a system of armed convoys. In 1565 a fleet system took on a regular form. Routing and timing were governed by prevailing natural conditions. The French and English resorted to privateering attacking the silver laden ships or the ports where the bullion was loaded in the Gulf of Mexico (Vera Cruz) or the Caribbean (Nombre de Dios).

The Spanish ships needed to be out of the Gulf of Mexico before the hurricane season and away from the coast of Cuba by early summer. Between 1550 and 1650 ships from Mexico and the isthmus of Panama converged on Havana where they took on water and supplies for the transatlantic voyage to Spain. The fleet bound for the isthmian Caribbean port of Nombre de Dios, known as Galeones, left San Lucar, the port of Seville, in mid-April. The Atlantic crossing took five to six weeks on average.

The number of vessels arriving in Nombre de Dios, ranged from 27.3 in the decade 1611-1620 to 20.0 in the decade 1681-1690. The size of the ships raising from 240 tons in the 1550s to 400 tons in 1600. Nombre de Dios was a fever ridden location, difficult to defend, and tended to be occupied only at the time of the arrival of the fleets. The ships retired once they had loaded or unloaded their cargoes to the well-fortified port of Cartagena on the northern coast of South America.

The Asian Connection

But above all the sliver of Potosí was desired in Asia, India and above all to China. In 1565 a direct round-trip link was established across the Pacific Ocean from the Americas when the pilot monk, Andres de Urdaneta, found the long-sought return route from the Far East to Mexico. To get to the Philippines from New Spain (Mexico) was relatively easy and the route was established in the 1540s. Ships needed to sail at a latitude of a least 10 degrees north of the equator in order to catch a favorable wind. The voyage took only eight to ten weeks.

In fact, getting to Manila from New Spain was a far easier and shorter voyage than getting to Peru from New Spain (Mexico). It was returning that posed the difficulties. Father Andres de Udaneta succeeded in making the connection between Manila and the Mexican coast by sailing north of the 38th parallel north, off the coast of Japan, before catching the eastward blowing “Westerlies” to take the route across the Pacific reaching the west coast of North America before sailing south to Acapulco.

Once discovered this route was followed by the galleons from Manila for over 250 years. The voyage took from four to six months and the loss among the crews was as high as thirty to forty percent. If the voyage lasted more than six months the ships could become floating coffins. In May 1657 the Manila galleon arrived off the Mexican coast under full sail, its treasures intact, but with everyone on board dead.

But a consequence of the establishment of the trans-Pacific round trip route was that one third of the silver produced in Spanish America between 1565 and 1815 went to the Far East by the Manila galleons, complementing the Portuguese dominated route from Europe around Africa and across the Indian Ocean through the Malacca Straits and into the South China Sea to the mouth of the Pearl River to Macao and Canton.

The opening of the trade to the East, and particularly to China, by these two seaborne routes had dramatic consequences. The products of Asia were of far higher quality than anything in Europe at the time. Silver was critical to European trade with the Orient. The Europeans produced nothing in the way of manufactured goods than the Asians did not produce better – weapons excluded.

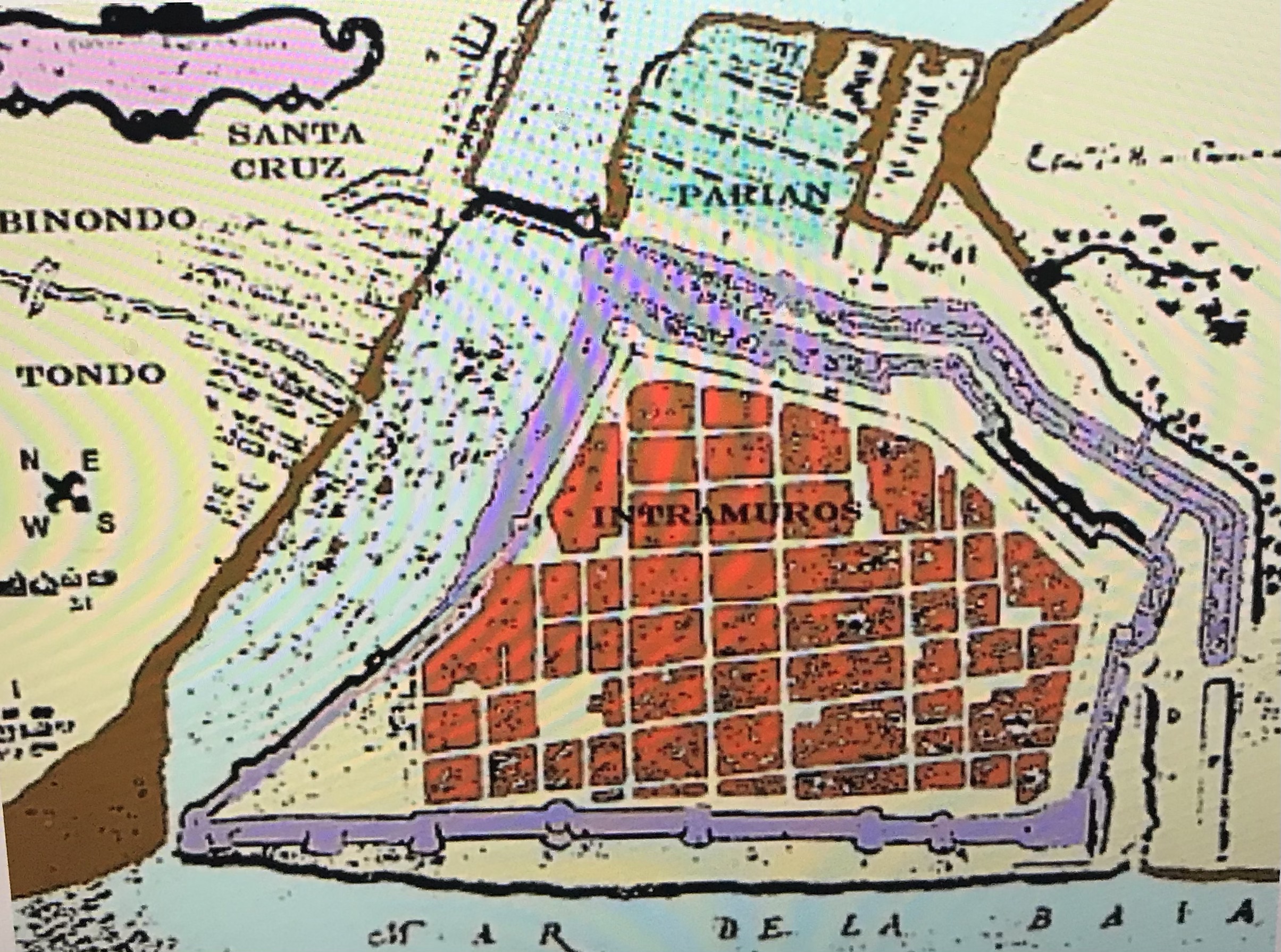

Silver was in great demand in India and China. Chinese porcelains and silks, damasks and satins, were exchanged for Spanish American silver in Manila which became a great entrepôt because of its fortuitous location at the intersection of two economic systems: The Chinese zone where silver was expensive and the Americas where silver was cheap. Chinese merchants in Manila, mainly from Fujian, lived in an intramuros area known as the Parian, and grew in number some 150 in 1564 to 30,000 in 1603.

The Chinese monetary system was especially responsive to the arrival to Spanish American silver. In the 1570s the Chinese moved from paper money to a silver-based system. China had one quarter of the world’s population and the largest taxing system in the world and silver became the only acceptable currency for paying taxes.

The re-export of silver from Spain to the Middle East, India, and China, and from Acapulco to Manila and on to China, also became profitable for Europeans in comparative terms: Silver-gold ratios (units of gold to one in silver) was 1/6 in China, 1/8 in India, and 1/12 in Europe. The Manila Galleons made the round trip across the Pacific once or twice a year. Philip ll decreed that the ships should be no more than 300 tones.

But in fact, the Manila Galleons, many built in the Philippines, were huge ships that combined the carrying capacity of carracks with the maneuverability and speed of caravels, reaching 2,000 tones, and carrying at times silver to the value of two and a half million silver pesos. The ships in New Spain (Mexico) were known as the “Nao de China”, literally the “Ship of China.”

Production of silver from the “Cerro Rico” grew rapidly peaking in 1592. The flow of Spanish American silver to Asia via Europe was facilitated when in December of 1580 Philip ll of Spain arrived in Lisbon to claim the crown of Portugal as Philip l of Portugal. He remained in Lisbon for three years overseeing the affairs of his vast empire.

Under the terms of approved by the Cortes of Tomar of 1581 which provided legal sanction for Phillip ll’s seizure of the Portuguese crown, the two empires in America were to remain administratively separate. The “union ibérico” of the crowns of Spain and Portugal lasted until 1640. And the union of the crowns of Spain and Portugal greatly facilitated the flow of silver from Seville to Lisbon and from Lisbon to India and China and Japan via the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

Much of the Spanish American bullion and coin ended up in India and China, and often by way of the ports and caravans of the Near East and Central Asia. The Mughals like the Ottomans and the Safavids used Potosi silver to finance their wars of conquest. The Potosi “piece of eight” was the world’s first global currency crossing frontiers and financing trade and wars.

The End of the Potosi Era

But the great Potosi silver facilitated global interconnected trade and finance network did not survive the 17th century. Competition to Spanish domination arose from the Protestant Dutch and from the French and from the English in Europe and in Asia and in the Americas.

By the mid-seventeenth century Potosi itself was faltering under the weight of declining mines, broken dams, and a great scandal at its core, in Potosi’s mint, where a colossal debasement scam undermined confidence in the value of the currency.

In the 1630’s debased Potosi silver bars with the Potosi mark were rejected by bankers on the money markets of Genoa and Antwerp. Potosi coins were no longer acceptable in the spice markets of India and South East Asia, and in Mughal India millions of suspect Potosi coins were recycled as rupees.

The Potosi “P” had become a synonym for poison. Portugal regained its independence from Spain in 1640 and with the assistance of the virulently anti-Catholic English Republic of Oliver Cromwell and of the English Fleet under the Parliamentarian Admiral Blake. English traders of the East India Company were beginning to find another locally produced (and far more destructive) and profitable Indian export that the Chinese loved as much as silver: opium.

By then the great days of Potosi were a thing of the past. Mexico’s silver sustained the Manila galleons until the beginning of the nineteenth century, and the Bourbon monarchs of Spain attempted to revive Potosi in the 1780s.

But in August 1780, the efforts by the Spanish authorities to impose a new Mita regime provoked the “Great Andean Rebellion” which began first at Pocoata, north of Potosi, led by Tomás Katari, an indigenous spokesman who had petitioned for reforms.

During November of the same year, south of Cuzco, a local cacique in the village of Tinta, José Gabriel Condorcanqui, taking the name Tupac Amaru ll, seized the local Spanish Corregidor, José de Arriaga, and executed him. The rebels rejected their Mita obligations totally.

Tupac Amaru ll knew Potosi well having been a mule train owner transporting coca and mercury to the “Imperial Vila.” Both Katari and Tupac Amaru ll were captured and executed. But the Andean rebellion flared and tens of thousands were killed.

The siege of La Paz in early 1781 was led by an indigenous rebel who called himself Tupac Katari. He had also been a small coca dealer who knew his way around the Andean mountains. He was captured in October 1781. Like the other rebel leaders he was sentenced to a gruesome death, and like Tupac Amaru ll, he was torn apart by horses and his body part displayed where his “crimes” had been most egregious in Spanish eyes. The Mita system was under challenge as never before.

But in 1825, after 15 years of struggle, Simon Bolivar, marked the end of the Mita, and of the “Vila imperial” of Potosi, and the “Liberator” symbolically proclaimed South American freedom from the summit of the Cerro Rico. The new Republic of Bolivia in the high Andes took his name.

But few recalled the central and pioneering role that Potosi and its silver had played in the sixteenth century in creating and facilitating the first globalized network of world interconnection.

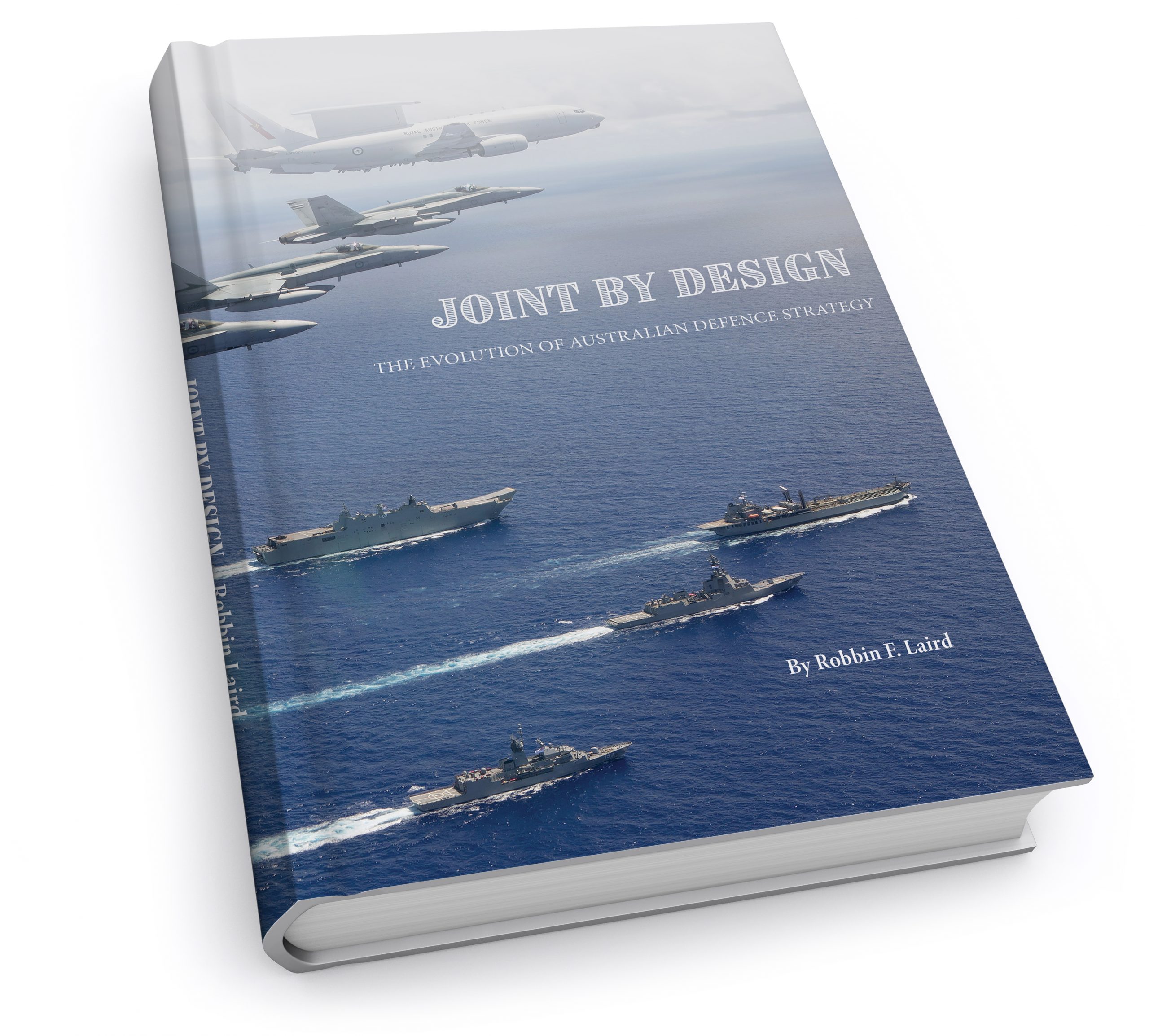

The featured graphic is of a Manila Spanish Galleon.

Manila Galleon (ca. 1590) Boxer Codex, Lilly Library, Indiana University