By Robbin Laird

Recently, the Marines tested their new forward base refueling system with the CH-53K.

The two together provide new capabilities for forward refueling points or for expeditionary basing.

According to the Marines:

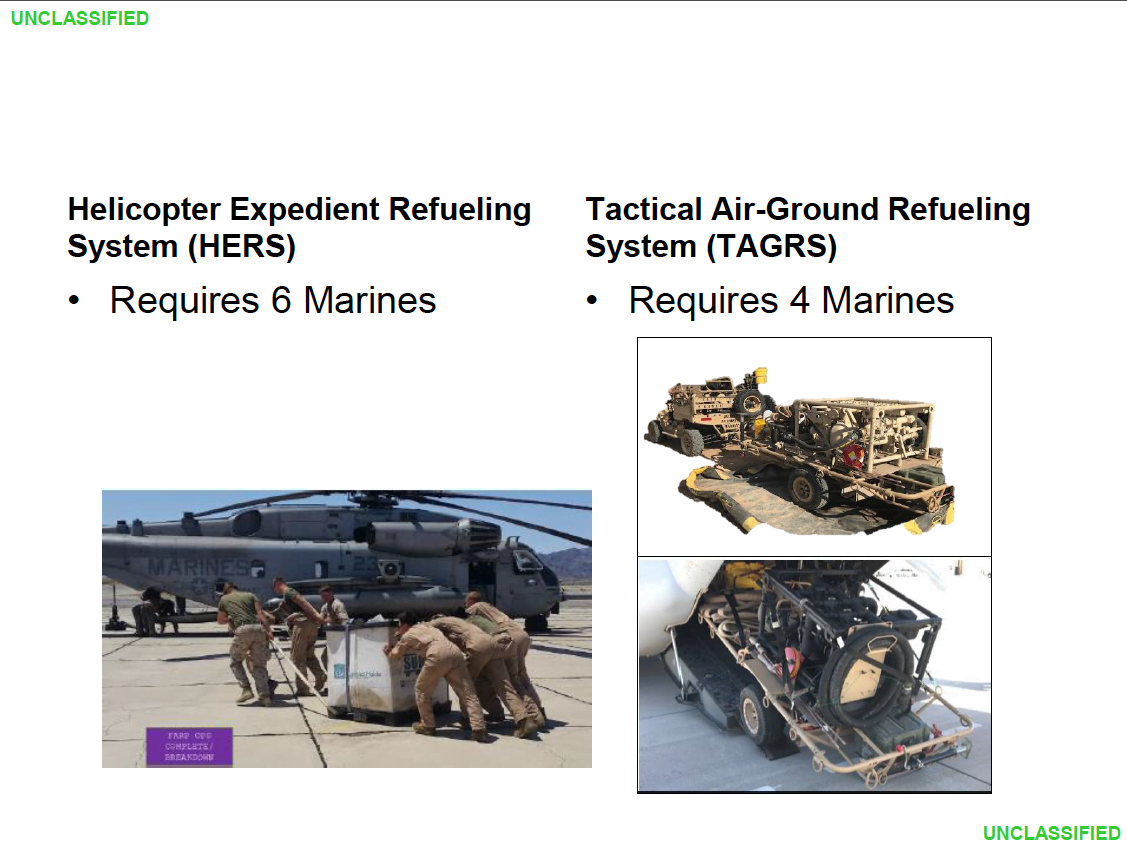

Marines with Marine Wing Support Squadron 371, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, employ a tactical aviation ground refueling system (TAGRS) while conducting expeditionary advanced base operations in support of a CH-53K King Stallion training evolution at a forward arming refueling point at Yuma Proving Grounds Range, Ariz., July 15, 2020.

The King Stallion is the most powerful aircraft in the Department of Defense, providing unmatched heavy-lift capability to the Marine Corps.

(U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Jaime Reyes)

In an interview earlier this summer with a senior MAWTS-1 officer, we discussed the coming of TAGRS and of the CH-53K to the Marine Corps and how these new capabilities would allow for enhanced FARP capabilities and expeditionary basing support.

In that interview with Maj Steve Bancroft, Aviation Ground Support (AGS) Department Head, MAWTS-1, MCAS Yuma, we discussed the way ahead on FARPs enabled by TAGR and CH-53Ks.

Excerpts from that interview follow:

There were a number of takeaways from that conversation which provide an understanding of the Marines are working their way ahead currently with regard to the FARP contribution to distributed operations.

The first takeaway is that when one is referring to a FARP, it is about an ability to provide a node which can refuel and rearm aircraft.

But it is more than that. It is about providing capability for crew rest, resupply and repair to some extent.

The second takeway is that the concept remains the same but the tools to do the concept are changing.

Clearly, one example is the nature of the fuel containers being used. In the land wars, the basic fuel supply was being carried by a fuel truck to the FARP location. Obviously, that is not a solution for Pacific operations.

What is being worked now at MAWTS-1 is a much mobile solution set.

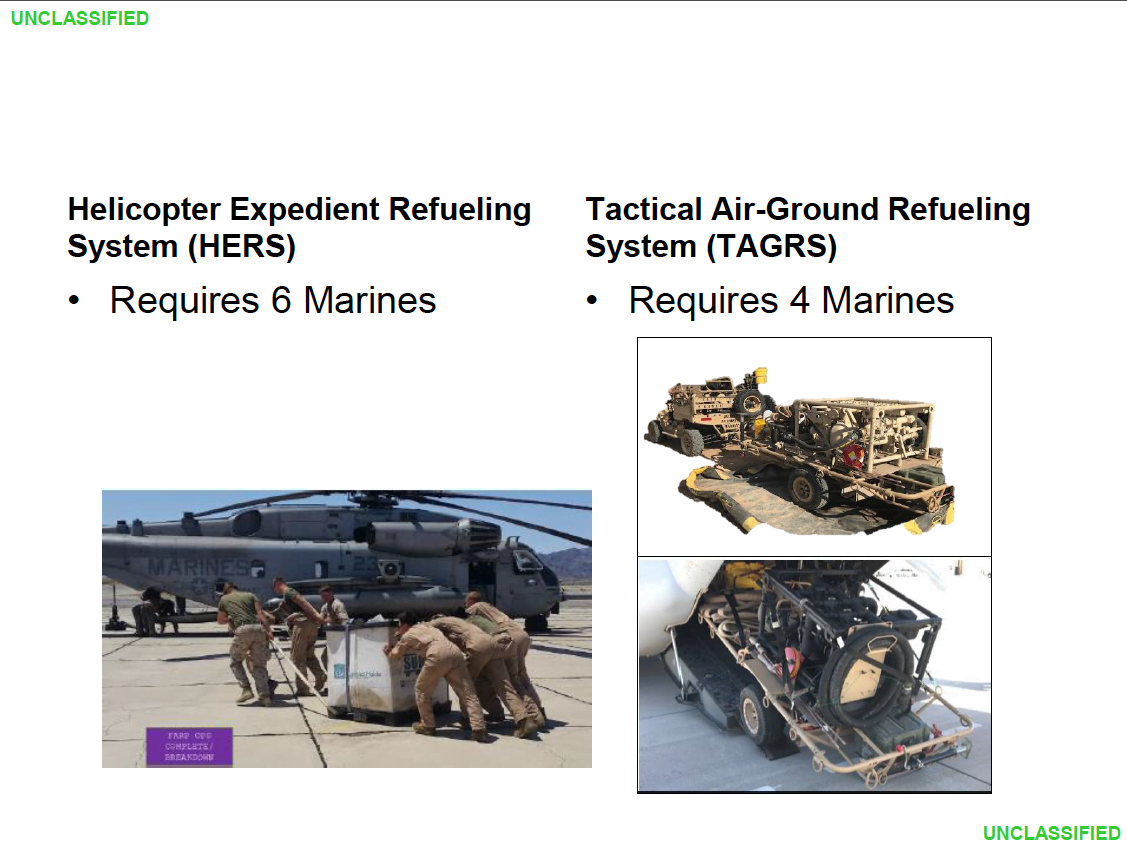

Currently, they are working with a system whose provenance goes back to the 1950s and is a helicopter expeditionary refueling system or HERS system.

This legacy kit limits mobility as it is very heavy and requires the use of several hoses and fuel separators.

Obviously, this solution is too limiting so they are working a new solution set.

They are testing a mobile refueling asset called TAGRS or a Tactical Aviation Ground Refueling system.

As noted in the discussion of TAGRS at the end of this article: “The TAGRS and its operators are capable of being air-inserted making the asset expeditionary.

“It effectively eliminates the complications of embarkation and transportation of gear to the landing zone.”

The third takeaway was that even with a more mobile and agile pumping solution, there remains the basic challenge of the weight of fuel as a commodity.

A gallon of gas is about 6.7 pounds and when aggregating enough fuel at a FARP, the challenge is how to get adequate supplies to a FARP for its mission to be successful.

To speed up the process, the Marines are experimenting with more disposable supply containers to provide for enhanced speed of movement among FARPs within an extended battlespace.

They have used helos and KC-130Js to drop pallets of fuel as one solution to this problem.

The effort to speed up the creation and withdrawal from FARPs is a task being worked by the Marines at MAWTS-1 as well.

In effect, they are working a more disciplined cycle of arrival and departure from FARPs.

And the Marines are exercising ways to bring in a FARP support team in a single aircraft to further the logistical footprint and to provide for more rapid engagement and disengagement as well.

The fourth takeaway is that innovative delivery solutions can be worked going forward.

When I met with Col. Perrin at Pax River, we discussed how the CH-53K as a smart aircraft could manage airborne MULES to support resupply to a mobile base.

As Col. Perrin noted in our conversation: “The USMC has done many studies of distributed operations and throughout the analyses it is clear that heavy lift is an essential piece of the ability to do such operations.”

And not just any heavy lift – but heavy lift built around a digital architecture.

Clearly, the CH-53E being more than 30 years old is not built in such a manner; but the CH-53K is.

What this means is that the CH-53K “can operate and fight on the digital battlefield.”

And because the flight crew are enabled by the digital systems onboard, they can focus on the mission rather than focusing primarily on the mechanics of flying the aircraft. This will be crucial as the Marines shift to using unmanned systems more broadly than they do now.

For example, it is clearly a conceivable future that CH-53Ks would be flying a heavy lift operation with unmanned “mules” accompanying them. Such manned-unmanned teaming requires a lot of digital capability and bandwidth, a capability built into the CH-53K.

If one envisages the operational environment in distributed terms, this means that various types of sea bases, ranging from large deck carriers to various types of Maritime Sealift Command ships, along with expeditionary bases, or FARPs or FOBS, will need to be connected into a combined combat force.

To establish expeditionary bases, it is crucial to be able to set them up, operate and to leave such a base rapidly or in an expeditionary manner (sorry for the pun).

This will be virtually impossible to do without heavy lift, and vertical heavy lift, specifically.

Put in other terms, the new strategic environment requires new operating concepts; and in those operating concepts, the CH-53K provides significant requisite capabilities.

So why not the possibility of the CH-53K flying in with a couple of MULES which carried fuel containers; or perhaps building a vehicle which could come off of the cargo area of the CH-53K and move on the operational area and be linked up with TAGRS?

I am not holding Maj. Bancroft responsible for this idea, but the broader point is that if distributed FARPs are an important contribution to the joint and coalition forces, then it will certainly be the case that “autonomous” systems will play a role in the evolution of the concept and provide some of those new tools which Maj. Bancroft highlighted.