By Robbin Laird

The strategic environment has clearly changed and the level of real world conflict has escalated, whether in terms of major hot wars – in the Middle East and in Europe – or in terms of active gray zone conflicts.

The ready force needs to deal with this real world rather than than just preparing for a future war. The DSR has outlined the future force for the future war; the current ADF needs to deal with the world we have.

The prospect of armed conflict in the first island chain, already underway in the gray zone between China and the Philippines, and the prospect of PRC actions against a sovereign free nation in Taiwan has been constantly threatened by the current leader of China.

How do you respond to the here and now but do so in a way that puts you on the trajectory which the DSR has mandated?

Some answers to this question were provided by three of the speakers at the September 26, 2024 Sir Richard Williams Foundation.

Their answers were in the form of identifying capabilities crucial to the ADF now which needed to be underscored and enhanced in the years to come.

The first speaker was Lt General Susan Coyle, Chief of Joint Capabilities. The Joint Capabilities Group is defined by the Australian government as follows:

Joint Capabilities Group (JCG) is headed by the Chief of Joint Capabilities (CJC), who is responsible to the Chief of Defence Force for the provision of Joint Health, Logistics, Education and Training, Information Warfare and Joint Military Police. CJC will also manage agreed Joint projects, and their sustainment, to support joint capability requirements.

Concomitant with her broad remit, Coyle discussed a range of efforts within the JCG. But the most important for this discussion was what she identified as the “high ground.”

Cyber power is a vital element of national military power. We need to coordinate electronic warfare and cyber information operations in order to gain asymmetric advantage and paralyze our adversary’s decision making. We must be able to continue to defend and exploit capabilities within the electromagnetic spectrum.

And I’ve heard this referred to recently as the next high ground. Doing so will slow adversaries kill chains and increase confusion and degrade their precision. The layering of electronic warfare, cyber and kinetic attacks is similarly vital for us to assuring our own strike capability.

We must protect radios and microwaves that are used for communications and radars, as well as infrared spectrum for our weapons guidance, jamming aircraft, blinding air defence, radars, suppressing military missile systems. All of this is absolutely real and at the forefront of our mind, and so we’re focused on delivering capability that will protect our ability to operate across the electronic magnetic spectrum.

Lt General Coyle put it bluntly:

If we lose the war in the electromagnetic spectrum, we lose the war across all domains.

Hence enabling the force in being to fight, survive and prevail in the current context is crucial and in so doing carves a path to shaping future options as well.

The second speaker weighed in on Coyle’s comments.

The speaker was Phil Winzenberg, the Deputy Director General-Signals Intelligence and Effects from the Australian Signals Directorate. He reinforced Coyle’s emphasis on the role of effective operations in the electromagnetic spectrum and signals intelligence as enablers for an integrated force..

In his presentation he underscored that the integrated force was more than the ADF and its operations.

This what he argued about the ASD and its current relationship with the ADF in creating a more integrated force:

That brings us to the present, where the demands from the ADF have increased ever further. Instead of just the land domain, which was the focus of previous conflicts, we will support the ADF in all domains. We won’t just provide intelligence on adversary capabilities, but also timely indicators and warnings of adversary intent towards the integrated force and also our nation’s critical infrastructure.

We won’t just provide situational awareness of the disposition of adversary platforms and forces, but we’ll do that also to establish and hold custody of them so that they can be used effectively by CJOC, at his or her discretion, and on a scale and with a complexity never encountered before by ASD or indeed the ADF.

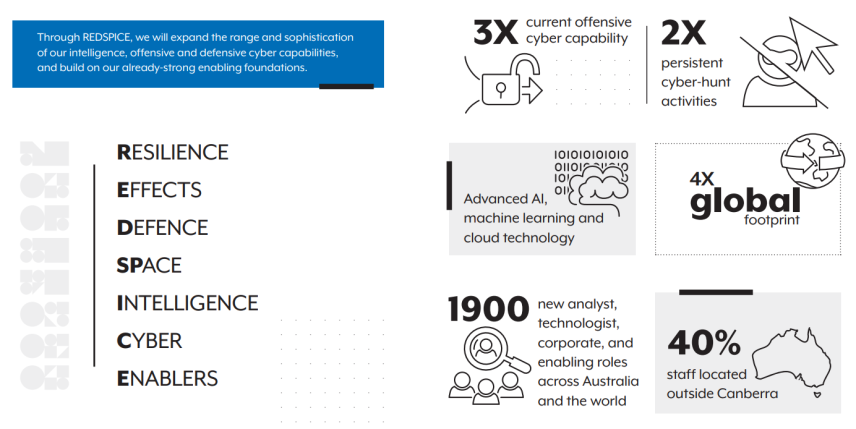

He then highlighted REDSPICE

This programmatic effort is described by the ASD as follows:

REDSPICE is the most significant single investment in the Australian Signals Directorate’s 75 years. It responds to the deteriorating strategic circumstances in our region, characterised by rapid military expansion, growing coercive behaviour and increased cyber attacks.

Through REDSPICE, ASD will deliver forward-looking capabilities essential to maintaining Australia’s strategic advantage and capability edge over the coming decade and beyond.

If you’re the type of person who is curious, motivated by finding a purpose and loves problem-solving, then you’re the type of person we’re looking for.

The REDSPICE Blueprint (PDF) offers some further insights into what REDSPICE will deliver, and a vision of what ASD will look like in the future.

Through REDSPICE, we will expand the range and sophistication of our intelligence, offensive and defensive cyber capabilities, and build on our already-strong enabling foundations.

- 3x current offensive cyber capability

- 2x persistent cyber-hunt activities

- Advanced AI, machine learning and cloud technology

- 4x global footprint

- 1900 new analyst, technologist, corporate and enabling roles across Australia and the world

- 40% of staff located outside Canberra

Winzenberg went on to underscore the following:

I can assure everyone here that delivering REDSPICE is an ASD top priority, and we’re doing all that we can to hold up our end of the bargain in supporting the future integrated force.

REDSPICE is supporting current and future operations from the strategic to the tactical. There is no defensive cyber activity that the integrated force plans or executes that doesn’t draw its threat intelligence or employ tools developed by REDSPICE. There is no information and cyber effects that the integrated force plans or executes that doesn’t happen without REDSPICE targeting intelligence and tools, and there’s no technical intelligence on weapon systems and other capabilities that allow us to develop countermeasures and build electronic attack algorithms that isn’t enhanced by REDSPICE.

He then underscored that the ADF-ASD partnership was enhanced by the Five Eyes alliance.

I’ll finish by reflecting on the power that comes from ASDs membership of the five eyes. The Five Eyes alliance is the greatest intelligence partnership the world has ever known…

The trust and depth of this partnership is the key differentiator between us and others in the region. The breadth and depth of what we do together is truly staggering.

If we set about trying to achieve that today from the standing start, it would be inconceivable that we would get to where we are now. We have good, good friends everywhere who willingly work with us. They work with us to build our capabilities. They work with us to secure our interests. They work with us to share intelligence so that we can understand the challenges of the world together and in similar ways.

He then concluded with this statement:

So to close, I’m going to leave you with three fun facts.

Number one, ASD is at its core a support to military organizations. We’re now driven to deliver REDSPICE to best support government and defence in our complex strategic environment.

Number two, partnerships are key to the integrated force, and the ADF has no better partner than ASD and our five eyes buddies as we all rise to the shared challenge.

And number three, last but not least, when it comes to actionable intelligence at the speed of relevance in a modern battle space, you only have two options, SIGINT or everything else, much, much, much too late.

The third speaker was the Chief of the RAAF, AIRMSHL Stephen Chappell. He focused on the importance of taking advantage of the geographical situation in which Australia finds itself.

In effect, by shaping the RAAF and the integrated force as a maneuver force, the ADF is able to use geographical depth to defend itself and at the same time able to deploy from various locations on its own continent to gain strategic and tactical advantage.

This is how he concluded his presentation:

We can create the tempo, confuse and complicate adversary targeting and project depth well beyond their shores by working together as a joint and integrated force working closely with interagency, industry partners, allies and partners. We can position and posture to deter and be prepared to respond.

What he was articulating was defence by maneuver in terms of geographical and operational (meaning an ability to leverage space and extended range ISR and C2 systems) depth.

He highlighted this approach as follows:

Going back to how to generate our depth. We’ve experimented using space and cyber in generating effects to gain advantage. We’ve integrated with the U.S. and Australian fleets and land forces across the primary area of military interest for us to execute multi domain strikes at range in defense of our territory and coalition forces.

Our war games show us how in the Indo Pacific we can effectively integrate capabilities and forces across domains and nationalities, operationally and strategically. They also show us that there is much more to be done, and therefore our services will have to continue to evolve to meet the requirements of multi-domain operations.

He provided further details in a earlier presentation as well. In the 27 September 2023 Sir Richard Williams Foundation seminar, he made the following comment:

AVM Stephen Chappell, Head of Military Strategic Commitments, focused on the symbiotic relationship between offense and defense with regard to multi-domain strike.

“Integrated air and missile defense and multi-domain strike are two sides of the same coin. By having an ability to protect our strike enterprises we enhance their credibility to strike back which ensures as well our enhanced deterrent capability.”

He underscored: “Passive defense is just as important not only for defending critical assets, but preserving our multi-domain strike capabilities in order to execute those left jabs and those right hooks necessary. The next layer of defense we’re thinking about is counter force. This in effect is multi-domain strike, the ability to reach out and defeat a threat to our homeland or to our forces. Deterrence by denial includes that defensive protection of the chin as we deliver effective left jabs and right hooks.”