Since 2013 the Sir Richard Williams Foundation seminars have focused on building an integrated fifth generation force.

Recent seminars have evolved from the acquisition of new platforms to the process of shaping and better understanding the environment in which the integrated force will prepare and operate.

Moreover, they have highlighted the challenges of acting independently at an accelerated tempo and in sustained, high intensity Joint operations involving peer competitors.

Within this narrative, the 2020 seminars will further develop the ideas associated with an increasingly sophisticated approach to Joint warfighting and power projection as we face increasing pressure to maintain influence and a capability edge in the region.

Following on from the October 2019 seminar titled ‘The Requirements of Fifth Generation Manoeuvre’, the 2020 series of seminars and lunches will examine:

- the emerging requirements associated with trusted autonomous systems, and

- information warfare, especially in relation to operations in cyberspace.

In doing so, they will each address how the Australian Defence Force must equip, organise, connect, and prepare for multi-domain operations. As ever, the Sir Richard Williams Foundation has identified pre-eminent speakers from across the Australian and international defence communities, as well as invited industry representatives to reflect the integral role they will play in the national framework of future operational capability.

Seminar Outline

Building upon the existing foundations of Australian Defence Force capability, the aim of the March seminar is to explore the force multiplying capability and increasingly complex requirements associated with unmanned systems. From its origins at the platform level, the opportunities and potential of increased autonomy across the enterprise are now expected to fundamentally transform Joint and Coalition operations.

The concept of the Unmanned Air System (UAS), or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), is nothing new nor is their use in missions which traditionally challenge human performance, fragility, and endurance.

Often described as the dull, dirty, and dangerous missions, unmanned systems have now provided the commander with a far broader range of options for the application of force against even the most challenging target sets. However, ongoing operational experience confirms unmanned systems on their own are not the panacea and trusted autonomy in manned and unmanned teaming arrangements in each environmental domain is emerging as the game changer.

The narrative is now forming across defence which has progressed the argument for greater numbers of unmanned systems in a far more mature and balanced way than hitherto. The manned-unmanned narrative is now sensibly shifting towards ‘and’, rather than ‘or’.

Manned and unmanned teaming leverages the strengths and mitigates the weakness of each platform and concentrates the mind on the important operational aspects, such as imaginative new roles, and the challenges of integration to generate the desired overwhelming firepower.

This capability will require a complex web of advanced data links and communication systems to make it operate as a combat system. Designing and building the ‘kill web’ so that it can enable the delivery of manned-unmanned firepower across domains will be a huge challenge not least due to the laws of physics. However, the ability to train, test, evaluate and validate tactics and procedures will add a whole new level of complexity to generate the ‘trusted autonomy’ required for warfighting.

The aim of the March 2020 seminar, therefore, will be to promote discussion about the near and far future implications of autonomous systems, and to build an understanding of the potential and the issues which must be considered in the context of the next Defence White Paper and Force Structure Review.

It will investigate potential roles for autonomous systems set within the context of each environmental domain, providing Service Chiefs with an opportunity to present their personal perspective on the effect it will have on their Service.

The seminar will also explore the operational aspects of autonomous systems, including command and control and the legal and social implications that affect their employment.

And finally the seminar will examine the current research agenda and allow industry an opportunity to provide their perspective on recent developments in unmanned air, land, surface and sub-surface combatants.

Each of which are opening new ways of warfighting and creating opportunities to reconceptualise Joint operations and move away from the platform-on-platform engagements which have traditionally characterised the battlespace.

WF_NGAS_26Mar2020_SynopsisandProgram

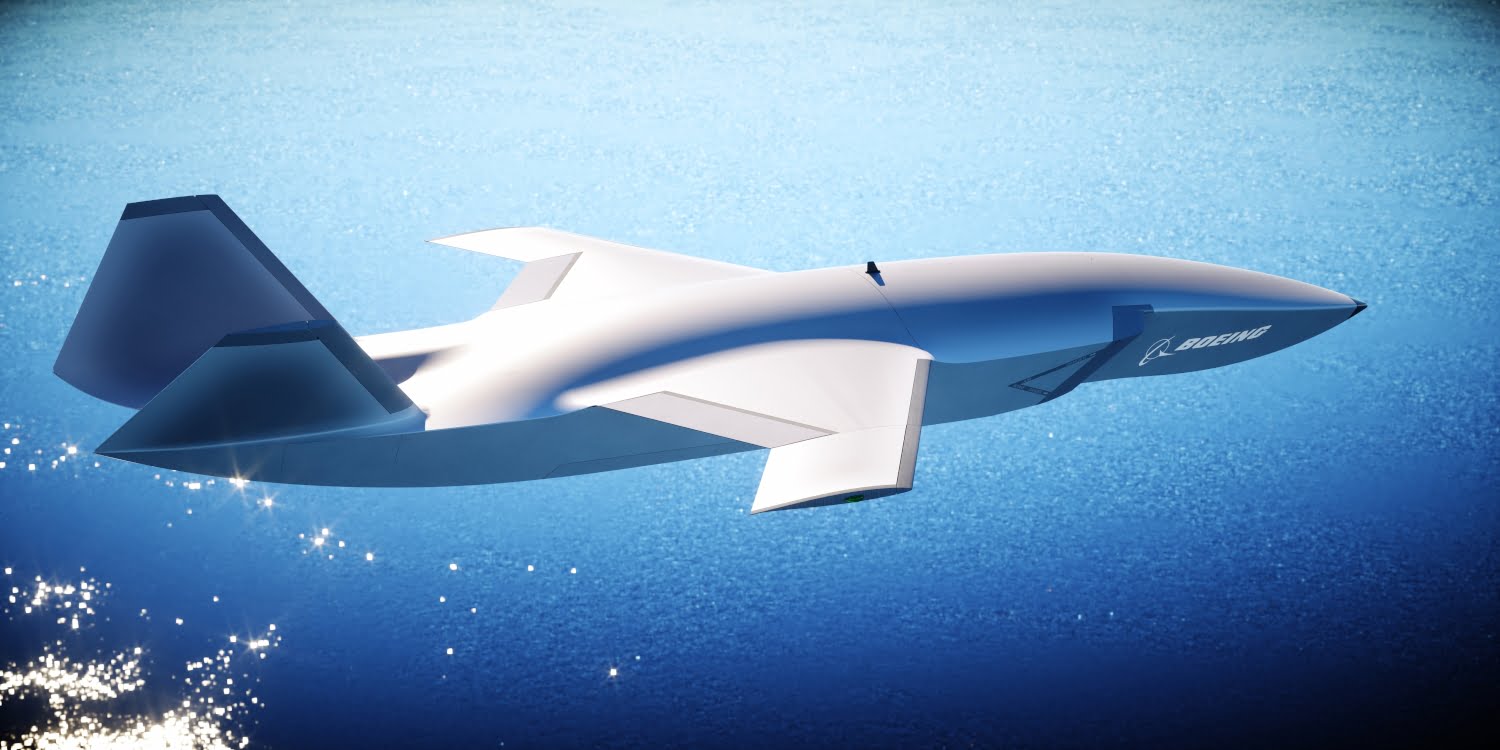

The featured image highlights the future loyal wingman aircraft being developed in Australia by Boeing.

A February 10, 2020 press release by Boeing Australia highlighted progress on the program:

BRISBANE, Australia, February 10, 2020 – The Boeing [NYSE:BA] Australia team recently completed major fuselage structural assembly for the first Loyal Wingman. The aircraft is one of three prototypes that will be developed as a part of the Loyal Wingman – Advanced Development Program in partnership with the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF).

“This is an exciting milestone for the development program, and the Australian aerospace industry, as we progress with production of the first military aircraft to be developed in Australia in more than 50 years,” said Dr. Shane Arnott, program director, Boeing Airpower Teaming System (ATS).

The Australian team has applied digital engineering and advanced composite materials to achieve cost and agility goals for the 38-foot (11.7-metre) aircraft, which is designed to use artificial intelligence in teaming with other manned and unmanned platforms.

“The partnership with Boeing is key to building our understanding of not just the operational implications for these sorts of vehicles, but also making us a smart customer as we consider options for manned-unmanned teaming in the coming decade,” said Air Commodore Darren Goldie, RAAF Director-General of Air Combat Capability. “Boeing is progressing very well with its development and we look forward to seeing the final product in the coming months.”

Arnott said Australian Industry participation had been critical to the program’s rapid development, with a 16-strong Australian industry team making key deliveries to date including:

- BAE Systems Australia, who have delivered hardware kits including flight control computers and navigation equipment;

- RUAG Australia, who have delivered the landing gear system;

- Ferra Engineering, who have delivered precision machine components and sub-assemblies to support the program; and

- AME Systems, who have delivered wiring looms to support the vehicle.

This first Loyal Wingman prototype will provide key lessons toward production of the ATS, which Boeing Australia is developing for the global defence market. Customers will be able to tailor ATS sensors and systems based on their own defence and industrial objectives.

The next major milestone will be weight on wheels, when the fuselage structure moves from the assembly jig to the aircraft’s own landing gear to continue systems installation and functional testing. The aircraft is expected to complete its first flight this year.

A March 7, 2019 article by Malcolm Davis on the loyal wingman program highlighted its importance for Australia:

One of the hottest debates among airpower analysts is the role of unmanned systems in future air combat. Australia may have just staked a lead in capability development of unmanned systems with the unveiling of the locally designed and built ‘Loyal Wingman’ unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) that is at the core of the Boeing Air Teaming System. The Loyal Wingman was unveiled in front of Defence Minister Christopher Pyne at the 2019 Avalon Airshow and Defence Expo last week.

Although it’s a Boeing platform, it will be designed and built entirely in Australia. That has some pretty significant implications for the future of Australia’s defence industry. It drives home the point that there’s more to this realm than just naval shipbuilding. It’s also a capability that is being planned with an export market in mind, to Five Eyes partners, and beyond. Australia will be able to position itself as a leading defence exporter of this type of capability as a result of the Loyal Wingman project.

And with its first flight slated for 2020, this is a capability that is not way off in the future with decades-long acquisition cycles. With Loyal Wingman, the aim is to produce an operational capability quickly—within the next few years.

Let’s start with what the platform is and why it’s important. The Loyal Wingman is designed to act as a force multiplier for manned fighters like the F-35A, F/A-18F Super Hornet and E/A-18G Growler, and larger manned aircraft like the E-7A Wedgetail or KC-30A refueller. Its primary role is projecting power forward, while keeping manned platforms out of harm’s way. It also seeks to protect ‘combat enablers’ like the Wedgetail from an adversary’s long-range offensive counter-air capability.

Although the planned aircraft is relatively small, according to Boeing it will have a range of more than 3,700 kilometres. That’s sufficient to operate over the South China Sea flying from RAAF Tindal near Darwin. It will carry integrated sensor packages to support intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) missions and electronic warfare (EW), and has an internal weapons bay that eventually could be armed with standoff weapons and precision bombs.

It will be able to fly autonomously, rather than being remotely piloted, which is vital. Exploiting trusted autonomy with the human ‘on the loop’ in an oversight role, rather than directly controlling the UCAV in every aspect of its mission ‘in the loop’, is a much more sensible approach to this sort of capability.

The Loyal Wingman can extend Australia’s air defence envelope much further north than would be possible using the F-35 alone. Imagine a swarm of Loyal Wingman UCAVs controlled by a four-ship formation of F-35s undertaking defensive counter-air tasks over the sea–air gap. The less stealthy UCAVs would be geographically located well away from the stealthy F-35s to avoid betraying their location, but close by in terms of being part of a resilient network. The F-35s in turn are networked to a Wedgetail to the rear. The UCAVs are the forward sensor in the ‘sensor to shooter’ link, but can also be a forward shooter, against an adversary equipped with long-range airpower, while the F-35s and Wedgetail can stay out of harm’s way.

Alternatively, in a role to support strike missions, the UCAVs could use their long-range ISR sensors and EW capabilities, and potentially precision-attack munitions, to identify and supress enemy integrated air defences. That would open up a path for the F-35s and fourth-generation aircraft like the Super Hornet and Growler to strike at high-value targets.

In both cases, long-range power projection and protection are of key importance. The Loyal Wingman could restore a significant amount of the long-range strike power the RAAF lost with the retirement of the F-111C in 2010. Although the Wingman is much smaller than the F-111C and carries a smaller payload, the emphasis on low-cost development means more UCAVs can be acquired. Local production will make it easier to keep on acquiring them as and when we need more. This will allow us to exploit combat mass and boost the potential of the RAAF’s future strike and air combat capability through swarming networks of autonomous shooters and sensors.

That’s a good move. One of the major challenges facing the RAAF is that by investing in very high-tech exquisite platforms like the F-35, which exploit technological overmatch against an opponent, the size of the air combat arm is constrained. It becomes a boutique force. In a future crisis against a major-power adversary, that would be a disadvantage—we can’t afford to lose any because we have too few fast jets in the sky. A larger force is better able to exploit Lanchester’s square law to the RAAF’s benefit. The Loyal Wingman begins that process of building a larger, more powerful RAAF, and that’s precisely the path Australia needs to take in preparing for the next war.

The Loyal Wingman will allow Australia to effectively exploit future air combat technology developments coming out of US programs like the US Air Force’s penetrating counter-airand the US Navy’s ‘F/A-XX’ (formerly known as ‘sixth-generation fighter’ projects), which will be based heavily on manned–unmanned teaming technologies. We are taking our first steps towards the types of platforms that could one day replace the F-35, and we are getting there faster than originally planned.

Learning to operate manned and unmanned systems as a network—a ‘system of systems’—is crucial. The key is not just resilient data links that maintain networks, but also the development of trusted autonomy so that platforms like Loyal Wingman don’t have to depend on human control.

That aspect may generate controversy. Advocates of a ban on lethal autonomous weapons (LAWs) are sure to challenge this project. Australia must resist calls for projects like Loyal Wingman to be cancelled on ethical or legal grounds. The platforms will depend on trusted autonomy, with humans ‘on the loop’, and any use of force will be made with human oversight. Unlike our adversaries who don’t need to adhere to legal and ethical constraints on LAWs, Western liberal democracies will always need to operate systems like Loyal Wingman with the laws of armed conflict in mind.

Finally, there are the defence industry and export benefits. Boeing Australia is designing and building the Loyal Wingman locally, establishing a sophisticated aerospace design and production capability. This could see Australia energise a new sector of its defence industry, complementing shipbuilding and other high-technology sectors. It would add to our defence export portfolio to key allies, including the Five Eyes countries. It would establish Australia as the leader in a global supply and support chain for Loyal Wingman operators around the world.

Loyal Wingman was the biggest story coming out of Avalon, and it may even surpass the F-35’s blazing performance in the skies as the cutting edge of future Australian airpower.

Malcolm Davis is a senior analyst at ASPI.