By Robbin Laird

The strategic shift from the land wars of the past two decades to preparing for the high-end fight is having a significant effect on the dynamics of change affecting the very nature of the C2 and ISR needed for operations in the contested battlespace.

An ability to prevail in full spectrum crisis management is highlighting the shift to distributed operations but in such a way that the force is integrateable to achieve the mass necessary to prevail across the spectrum of operations.

Much like the character of C2 and ISR is changing significantly, training is also seeing fundamental shifts as well.

For the US Navy, training has always been important, and what is occurring in the wake of the changes in the national security strategy might appear to be a replication of what has gone down for the past twenty years; but it is not.

In fact, it is challenging to describe the nature of the shift with regard to training.

Much like the shifts in C2 and ISR which I have discussed with the Navy’s Air Boss in a recent interview, the shifts in training are equally significant.

Indeed, when I visited San Diego last Fall, I had a chance to talk with Vice Admiral Miller about how one might conceptualize the nature of the shift in training for the US Navy.

In that article, the discussion highlighted a number of the changes underway but the target goal was highlighted by the Air Boss as follows: Training is now about shaping domain knowledge for the operational force to ensure that “we can be as good as we can be all of the time.”

With the focus on ensuring the capability of the distributed fleet to deliver the desired effects throughout the spectrum of conflict and crisis management, the goal is for the sailors, operators and leaders of the combat force to have the most appropriate skill sets available for the 21stcentury fight.

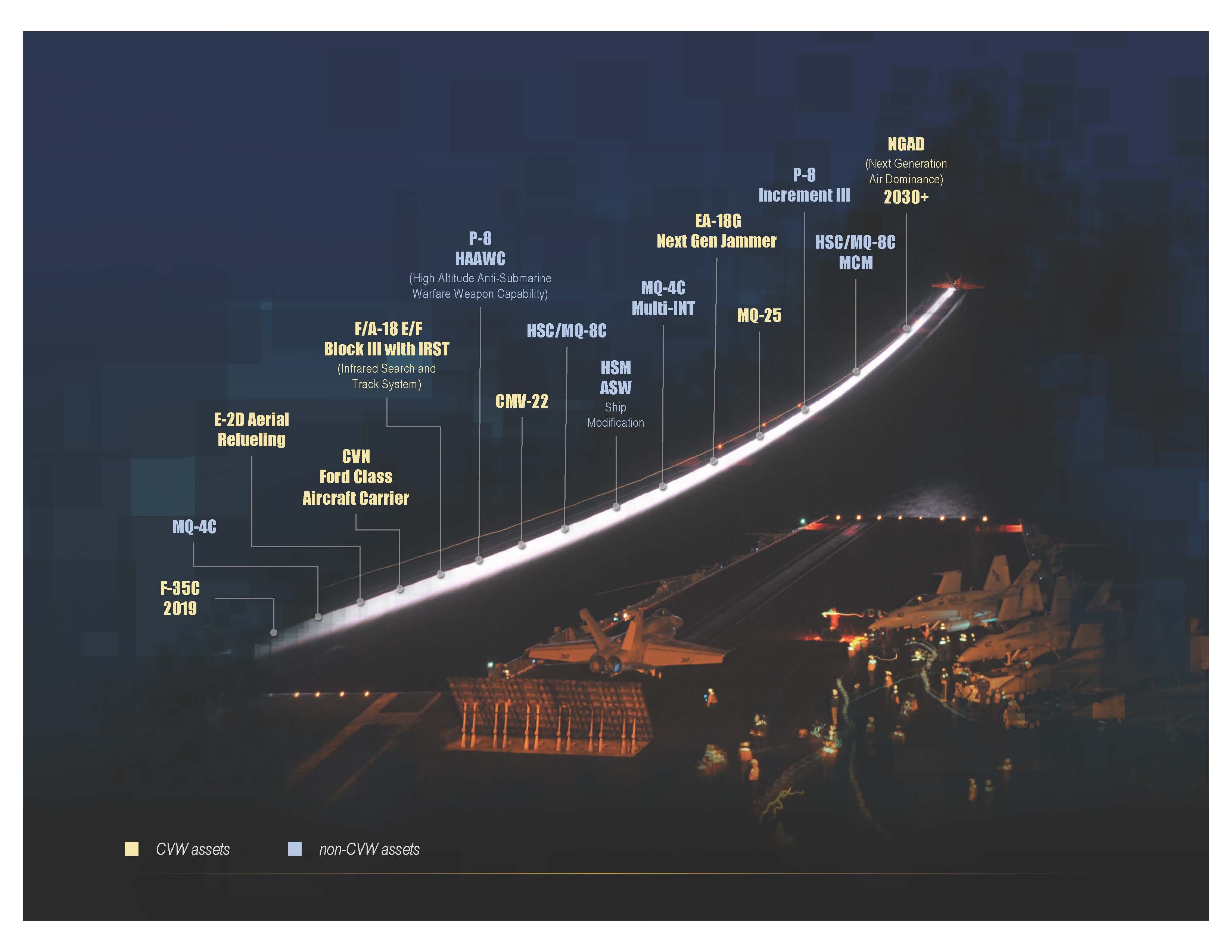

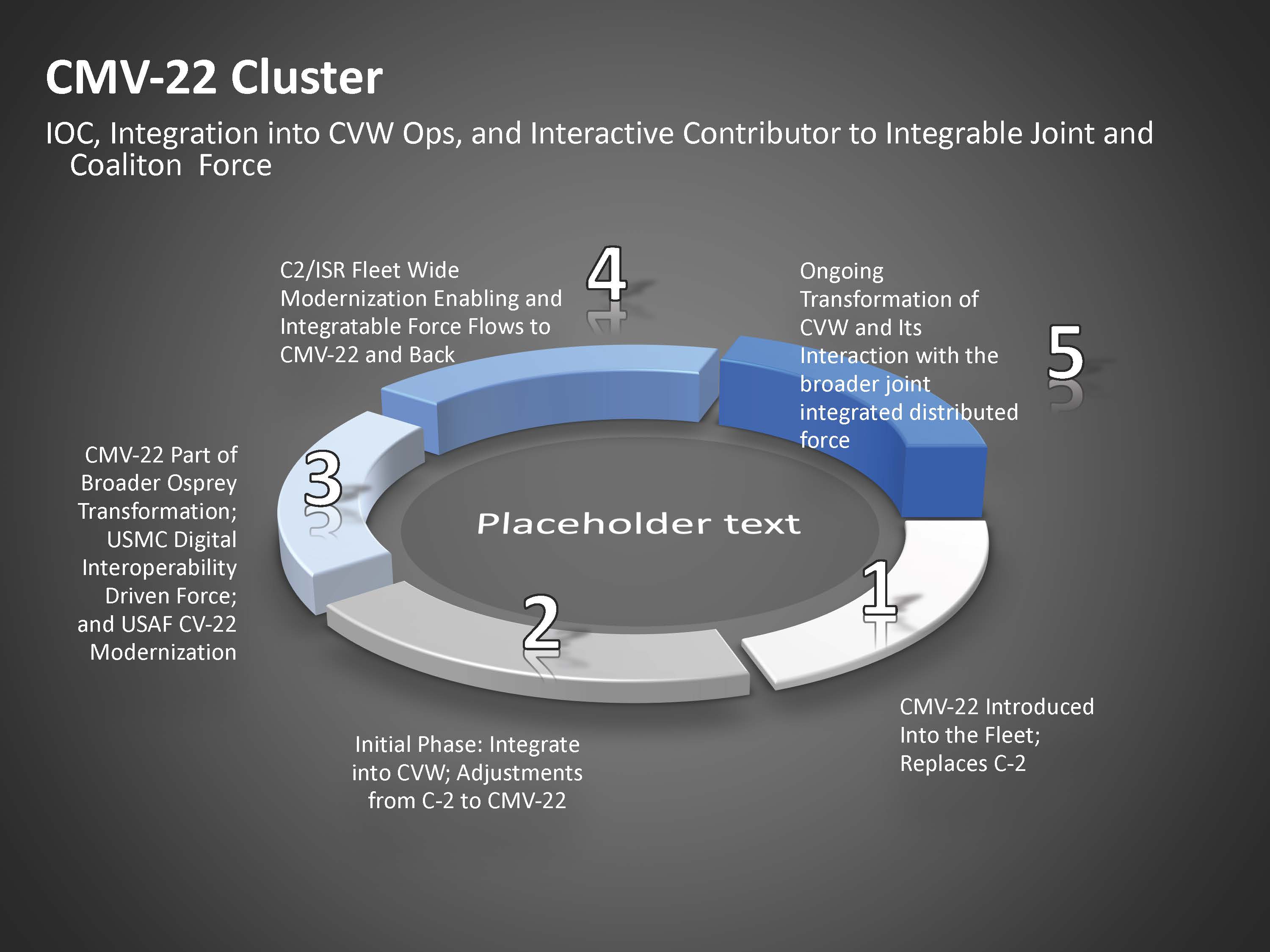

And with the introduction of new technologies into the fleet, ranging from the new capabilities being provided for the integrateable air wing, to the expanded capabilities of the surface fleet with the weapons revolution and the evolution of the maritime remote extenders, to the return to a priority role for ASW with the submarine fleet and the maritime reconnaissance assets working together to deliver enhanced capabilities to deter and to defeat adversarial subsurface assets, the dynamics of training change as well.

For example, with software upgradeable aircraft, the capabilities of the aviation assets you operated with on your last tour are likely to not be the same as you will deploy with in your next tour.

In a visit to Norfolk last Fall, Rear Admiral Peter Garvin, Commander of the Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Group (MPRF), we discussed how he saw the training challenge evolving.

There is an obvious return to the anti-submarine mission by the U.S. and allied navies with the growing capabilities of the 21st century authoritarian powers. However, as adversary submarines evolve, and their impact on warfare becomes even more pronounced, ASW can no longer be considered as a narrow warfighting specialty.

This is reflected in Rear Admiral Garvin’s virtuous circle with regard to what he expects from his command, namely, professionalism, agility and lethality. The professionalism which defines and underpins the force is, in part, about driving the force in new innovative directions. To think and operate differently in the face of an evolving threat. Operational and tactical agility is critical to ensure that the force can deliver the significant combat effect expected from a 21st century maritime reconnaissance and strike force.

Finally, it is necessary but insufficient to be able to find and fix an adversary. The ability to finish must be realized lest we resign ourselves to be mere observers of a problem.

And it is not simply about organic capabilities on your platform. The P-3 flew alone and unafraid; the dyad is flying as part of a wider networked enterprise, and one which can be tailored to a threat, or an area of interest, and can operate as a combat cloud empowering a tailored force designed to achieve the desired combat effects.

The information generated by the ‘Family of Systems’ can be used with the gray zone forces such as the USCG cutters or the new Australian Offshore Patrol Vessels. The P-8/Triton dyad is a key enabler of full spectrum crisis management operations, which require the kind of force transformation which the P-8/Triton is a key part of delivering the U.S. and core allies.

How do you train your P-8 team to be to work with the gray zone assets to deliver the kind of crisis management effect you want and need?

Clearly, the training mission is evolving to prepare for the high-end fight, and indeed, preparing to operate across the spectrum of crisis management.

But how best to describe the kind of evolution training for the fleet is undergoing?

To continue further throughout on how best to do so, I had the chance to visit Norfolk this month to discuss the focus and the challenges with three admirals who are key players in shaping a way ahead.

My host was Rear Admiral Peter Garvin, and he invited two other admirals as well to the discussion.

The first Rear Admiral John F. Meier, head of the Navy Warfare Development Command, with whom Ed Timperlake and I had met with when he was the CO of the USS Gerald R. Ford.

The second was Rear Admiral Dan Cheever, Commander, Carrier Strike Group FOUR.

The day before Ed and I met with Rear Admiral Gregory Harris, the head of N-98, who introduced into our discussion a key hook into my discussions with the three admirals in Norfolk.

We were discussing the evolving role of Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center at Fallon and the Admiral referred to Carrier Strike Group FOUR as a “mini” Fallon, which was, of course, suggestive of the dynamics of change within training.

We had a wide-ranging discussion about a number of issues, but I will focus here on our discussion about the dynamics of change revolved around the training concept or construct.

What I will identify are my take-aways from the conversation, which I am not going to attribute to any one admiral, or even suggest that there was a consensus on the points I will identify.

What I am providing are key takeaways from my perspective of how the Navy is addressing the dynamics of training for the high end fight or in my terms, operating across the full spectrum of crisis management.

For me, the ability to operate across the full spectrum of crisis management highlights the central contribution which the Navy-Marine Corps team delivers to the nation.

Operating from global sea-bases, with an ability to deliver a variety of lethal and non-lethal effects, from the insertion of Marines, to delivering strategic strike, from my perspective, in the era we have entered, the capabilities which the Navy-Marine Corps teams, indeed all of the sea services, including the Military Sealift Command and the US Coast Guard, provide essential capabilities for the direct defense of the nation.

One key challenge facing training is the nature of the 21stcentury authoritarian powers.

How will they fight?

How will their evolving technologies fit into their evolving concepts of operations?

What will most effective deter or provide for escalation control against them?

There is no simple way to know this.

When I spent my time in the US government and in government think tanks, I did a great deal of work on thinking through how Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces might fight.

That was difficult enough, but now with the Chinese, Russians, and Iranians to mention three authoritarian regimes, it is a challenge to know how they will operate and how to train to deter, dissuade, or defeat them.

A second challenge is our own capabilities.

How will we perform in such engagements?

We can train to what we have in our combat inventory, we can seek to better integrate across joint and coalition forces, but what will prove to be the most decisive effect we can deliver against an adversary?

This means that those leading the training effort have to think through the scope of what the adversary can do and we can do, and to shape the targets of an evolving training approach.

And to do so within the context of dynamically changing technology, both in terms of new platforms, but the upgrading of those platforms, notably as software upgradeability becomes the norm across the force.

The aviation elements of the Marine Corps-Navy team clearly have been in advance of the surface fleet in terms of embracing software upgradeability, but this strategic shift is underway there as well.

The Admirals all emphasized the importance of the learning curve from operations informing training commands, and the training commands enabling more effective next cycle operations.

In this sense training, was not simply replicating skill sets but combat learning reshaping skill sets as well.

Clearly, the Admirals underscored that there was a sense of urgency about the training effort understood in these terms, and no sense of complacency whatsoever about the nature of the challenges the Navy faced in getting it right to deal with the various contingencies of the 21stcentury fight.

The Navy has laid a solid foundation for working a way ahead and that is based on the forging of an effort to enhance the synergy and cross linkages among the various training commands to work to draw upon each community’s capabilities more effectively.

Specifically, NAWDC (Naval Air Warfare Development Center), SMWDC (Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center), UWDC (Undersea Warfare Development Center), NIWDC (Naval Information Warfare Development Center) and exercise and training commands, notably Carrier Strike Groups FOUR and FIFTEEN, are closely aligned and working through integrated operational approaches and capabilities.

When we visited Fallon in the past, we have seen the evolution not just in terms of naval integration (with surface warfare officers at Fallon) but the working relationships with Nellis (USAF) and MAWTS-1 (USMC).

And given the evolution of the USMC, the Navy teams with Marine Expeditionary Forces (MEFs), Marine Air Ground Task Force Training Command (MAGTAFTC), and Expeditionary Operations Training Group (EOTGs) in order to train the Navy and Marine Corps Team, notably with regard to the activities of CSG-4/15 for exercises.

Naval Warfare Development center is at the heart of Navy training for their all domain focus and efforts. NWDC isthe key Warfare Development Center which bridges the tactical to the operational and even the strategic level.

The synergy across the training enterprise is at the heart of being able to deliver the integrated distributed force as a core warfighting capability to deal with evolving 21stcentury threats.

There are a number of key drivers of change as well which we discussed.

One key driver is the evolution of technology to allow for better capabilities to make decisions at the tactical edge.

A second is the challenge of speed, or the need to operate effectively in a combat environment in which combat speed is a key aspect, as opposed to slo mo war evidenced in the land wars.

How to shape con-ops that master C2 at the tactical edge, and rapid decision making in a fluid but high-speed combat environment?

In a way, what we were discussing is a shift from training preparing for the next fight with relatively high confidence that the next one was symmetric with what we know to be a shift to proactive training.

How to shape the skill sets for the fight which is evolving in terms of technologies and concepts of operations for both Red and Blue?

In short, the Navy is in the throes of dealing with changes in the strategic environment and the evolving capabilities which the Navy-Marine Corps team can deploy in that environment.

And to do so requires opening the aperture on the combat learning available to the fleet through its training efforts.

The featured photo shows the Ohio-class fleet guided-missile submarine USS Florida (SSGN 728) transits the Mediterranean Sea, Aug. 27, 2019. Florida, the third of four SSGN platforms, is capable of conducting clandestine strike operations, joint special operation forces operations, battle space preparation and information operations, SSGN/SSN consort operations, carrier and expeditionary strike group operations, battle management and experimentation of future submarine payloads. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jonathan Nelson/Released).

This platform illustrates the opportunity and challenge for US Navy training: how to leverage the wide range of capabilities which this platform can deliver to the force. How to provide its capabilities to the integrated distributed force?

Training across the Navy and the joint force is required to do so.

U.S. Navy Biographies - REAR ADMIRAL DANIEL L. CHEEVER

U.S. Navy Biographies - REAR ADMIRAL JOHN F. OSCAR MEIER

U.S. Navy Biographies - REAR ADMIRAL PETER A. GARVIN