By Robbin Laird

With the central role which crisis management will play for the US and its allies, a key area of change is in the area of C2. Distributed operations which will be an essential part of the strategic shift will require distributed C2.

And C2 will have to operate in degraded operations environments.

A tested technology which can provided capabilities to support flexible insertion forces in the higher end and support for HADR operations on the lower end is the GATR system.

The GATR system provides a very flexible, mobile, deployable solution to ensure for reliable communications on the fly which can be used to support military insertion forces or to provide for connectivity when natural disasters have brought down normal operating systems.

I recently had a chance to talk with Cubic’s Victor Vega, Director of Emerging Solutions, about the GATR system.

I first became aware of both Mr. Vega and GATR from the role of the system in dealing with the HADR situation in Puerto Rico in 2017.

In an article by Debra Werner of Space News published on December 5, 2017, the role of GATR was highlighted.

Cubic Corporation’s GATR satellite antennas continue to provide communications links for residents and community leaders in Puerto Rico more than two months after Hurricane Maria devastated the U.S. territory and nearby Caribbean islands.

Employees of GATR Technologies, part of Cubic Corporation’s Mission Solutions Division, were in the U.S. Virgin Islands working to reestablish communications in the wake of Hurricane Irma, when Help.NGO’s Disaster Immediate Response Team and Cisco Systems’ Tactical Operations Team called for assistance in Puerto Rico.

Victor Vega, GATR Technologies director of emerging solutions, and his colleagues packed inflatable satellite antennas in suitcases and brought them to areas of Puerto Rico where hurricane-force winds and fallen trees had dismantled the terrestrial communications infrastructure. They installed inflatable GATR 2.4 meter antennas on rooftops, including two U.S. Army National Guard buildings that served as a distribution point for food and water.

Vega noted that he has been with the GATR program from the early days when it was produced by a small startup company (GATR Technologies) which was acquired by Cubic Corporation in 2015.

He argued that the acquisition has been good for the GATR effort as “We have been able to move from being an antenna provider to being part of a broader effort to become a satcom provider and to provide systems to DoD as a program of record.”

But he underscored that the core GATR capability is really about rapid response. He pointed out that when they began, the already contributed capability to the Hurricane Katrina disaster. The factory is located in Huntsville, Alabama and they put GATR into a truck and drove to the disaster area and provided sat com capabilities for the first responders.

“The prototype already allowed FEMA to get Internet access so people could come in and fill out the FEMA request forms and to communicate with their familes to let them know they were alright.”

He underscored that since that time, the GATR system has been a frequent contributor to HADR C2. The graphic below shows the HADR events at which GATR has provided C2 in a degraded operational environment.

Verga argued that given the centrality of communications to modern society, re-establishing C2 has become a central focus for relief agencies which providing HADR rebuild efforts. “The faster C2 can be restored, the more rapidly can order be re-established and chaos mitigated.”

GATR has virtually no logistics footprint so to speak. It can be packed along with suitcases for transport with other cargo; it does not need specialized vans or specialized lift helos or aircraft to bring to the area of interest. The small logistical footprint means it can be brought to the area of interest by a wide range of ground or air or sea transport systems.

This also means for insertion forces in higher end contingencies, a distributed C2 capability can be laid down rapidly and with minimal lift required. The system can be and has been carried with airborne troops and precision air dropped to the area of interest as well.

Because the focus is shifting from the big established bases of the Middle East land wars, to an ability to operate across the combat spectrum in a crisis situation with distributed forces, such a flexible coms capability is an essential part of the mobility and flexibility which the evolving force structure needs to prioritize.

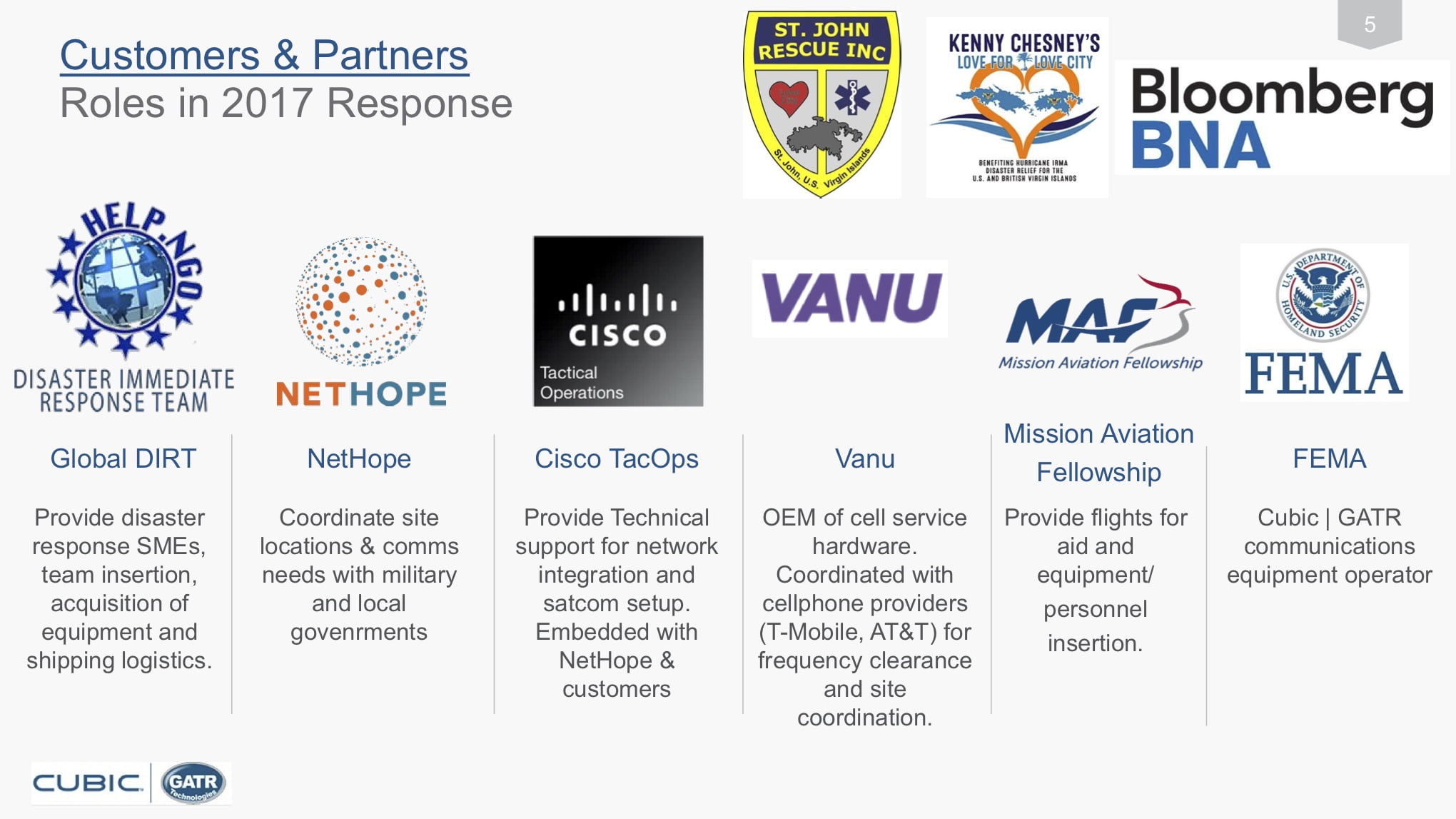

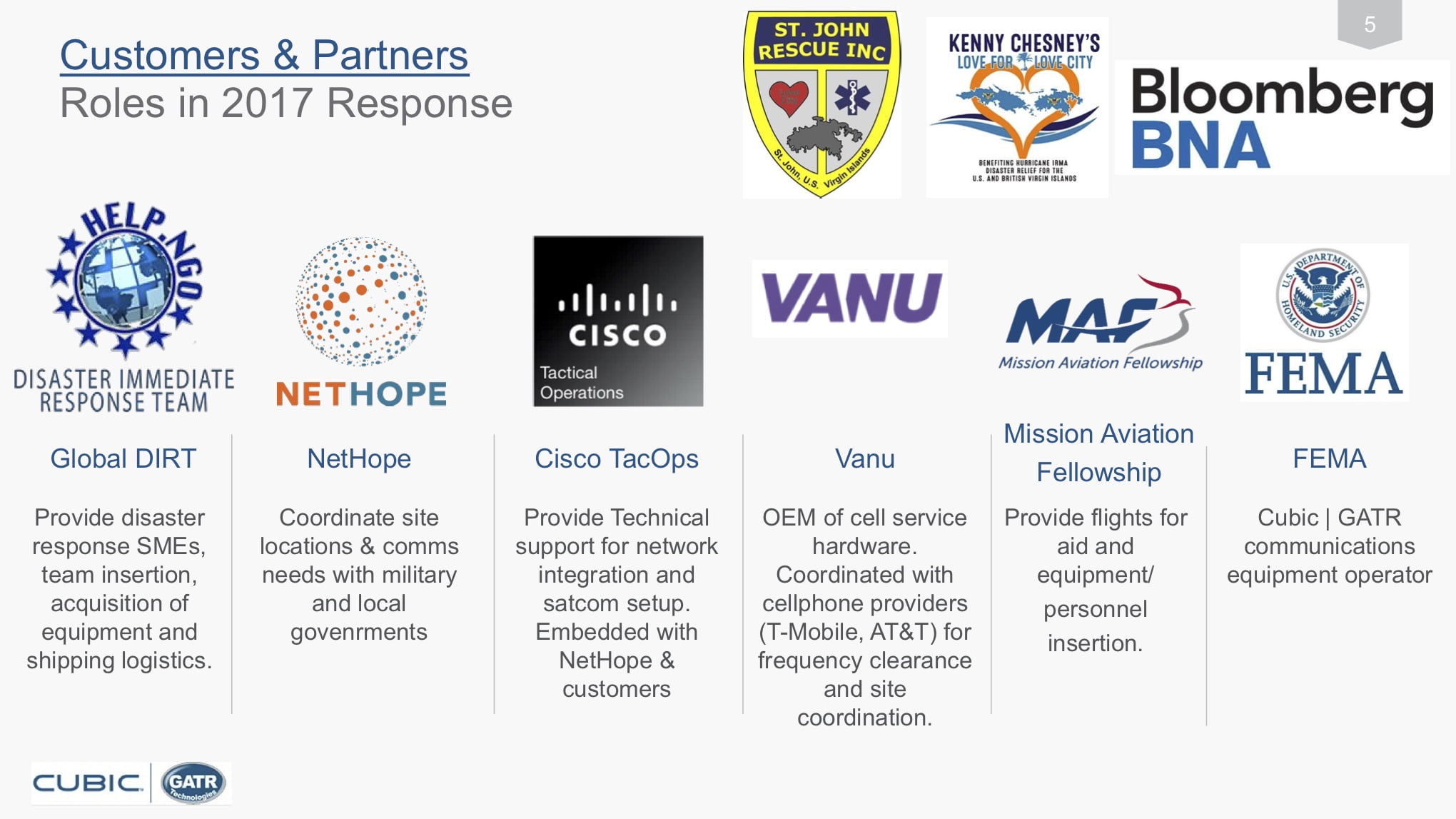

With regard to HADR operations, FEMA has become a customer of GATR as well as several NGOs which operate in the HADR environment. For example, in HADR operations in 2017, the following partners worked with GATR in support of operations:

In other words, GATR can support a wide range of missions operating in a disrupted or degraded environment.

I noted that the US military is clearly reworking island hopping as part of the US-allied strategy in the Pacific.

Vega commented that GATR clearly has a role in such a strategy and provided this example.

A US Army Unit based in Hawaii has been using GATR for some time to support exercises across the Hawaiian Island chain.

One of the officers of this particular unit told Vega that “we can not do our mission operating out of ice cream truck satcom. We cannot move all that equipment and get our job done.”

To do their mission, this US Army unit transitioned from the legacy system of trucks and antennas to GATR, a clear harbinger for a more flexible approach, one needed for HADR or other mission sets.

The featured photo shows Cubic’ Corporations’s Victor Vega installing GATR Technologies’ inflatable antenna on rooftop on City Hall in Vieques, Puerto Rico.

Photo taken from the Space News story cited above.