2018-01-09 By Richard Weitz

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS)—if fully executed in the Pentagon’s upcoming National Defense Strategy in January and its Nuclear Posture and Ballistic Missile Defense Reviews in February—would provide robust protection against WMD threats, whether wielded by terrorists or hostile countries.

Reflecting the bipartisan foundation of cooperation against WMD threats, the administration notes that these moves will build on existing U.S. and international counter-proliferation initiatives.

Administration representatives have made clear that they are “determined to prevent or deter WMD use of any kind” since employment “lowers the threshold for others.”

The NSS indirectly justifies last April’s U.S. missile strikes in Syria to discourage further WMD use by any actor.

The text warns state terrorism sponsors that Washington will hold them responsible for any proxy use of WMDs.

It tells the terrorists directly that the United States will join with foreign allies and partners to employ all means to target their “WMD specialists, financiers, administrators, and facilitators.”

The NSS supports new initiatives for detecting and disrupting WMD smuggling, enhancing counter-proliferation missions, targeting WMD terrorist enablers, increasing integration among counter-WMD capabilities, and bolstering homeland missile defenses.

The text further stresses the importance of fortifying the U.S. resilience against all kinds of mass attacks since better preparedness can help deter attacks as well as limit their damage. For this reason, the administration will work with foreign as well as domestic partners, including the private sector and civil society, to counter WMD terrorist threats.

Yet, the new strategy rejects the idea that the United States can simply fortify its borders and be safe.

As Christopher Ford, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for WMD and Counterproliferation on the National Security Council, observed at Hudson Institute in mid-November, “crude isolationism” is a flawed approach given that WMD terrorist threats exploit “global networks, and that sensitive nuclear or radiological material acquired anywhere could be used against U.S. interests either at home or abroad.”

Unlike the Obama administration’s strategies, Trump’s NSS does not reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the short term or envisage a nuclear-free world in the long run.

Administration officials have argued that such thinking and statements has weakened the credibility of U.S. extended deterrence guarantees and encouraged other states to seek nuclear weapons.

The current NSS, like previous strategies, supports retaining a triad of nuclear delivery vehicles, modernizing U.S. nuclear command and control networks, and upgrading the U.S. nuclear enterprise of scientific, engineering, and manufacturing capabilities.

One novelty is that Trump’s NSS affirms that U.S. nuclear forces can avert “non-nuclear strategic attacks” as well as conventional and nuclear aggression.

This is an apparent reference to deterring cyber strikes against U.S. critical infrastructure.

The section on cyber security remarks that, “the United States will be risk informed, but not risk averse, in considering our options” to thwart malign cyber actors.

Such deliberate ambiguity is likely designed to both deter cyber threats while also reassuring partners that U.S. officials will consider the risks of inadvertent escalation without being paralyzed by such a dynamic.

Yet, the NSS does not call for a massive U.S. nuclear weapons buildup.

The text affirms readiness for dialogue and verifiable arms control to limit nuclear risks and bolster strategic stability.

For example, administration officials have pledged to reduce excess U.S. nuclear material and warned that the growth of nuclear arsenals in Russia and South Asia raise nuclear security as well as nonproliferation challenges for the international community.

The NSS explicitly affirms that Washington “does not need to match the nuclear arsenals of other powers.”

The United States only needs to maintain a force “that meets our current needs and addresses unanticipated risks” in fulfilling the missions of deterring hostile powers, reassuring partners and allies, and attaining unspecified “U.S. objectives if deterrence fails.”

These goals likely include defeating aggressors and minimizing damage from adversary strikes.

Regarding the latter, and likely foreshadowing the Ballistic Missile Defense Review to be released in February, the NSS envisages “a layered missile defense system focused on North Korea and Iran to defend our homeland against missile attacks.”

These layers are bolstered by a sensor network ranging from satellites, terrestrial radars, and information-empowered aviation platforms such as the F-35.

The NSS says the United States will help partners and allies to “procure interoperable missile defense and other capabilities to better defend against active missile threats.”

Of these missile defense systems, only the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense program provides a direct defense of the U.S. homeland from ICBMs.

The system uses multistage solid-fuel boosters, the Ground-Based Interceptors (GBIs) stationed in Alaska and California, to ram an unarmed “kill vehicle” into warheads flying through outer space, obliterating them before they can re-enter the atmosphere.

The kill vehicle is being redesigned to make it more effective while the number of operational GBIs is increasing, though not fast enough.

The NSS is but the latest report to express alarm that countries hostile to U.S. interests are obtaining more missiles with greater ranges and accuracy.

In particular, the text relates how North Korea’s growing portfolio of missiles could deliver nuclear, biological, or chemical munitions.

Undoubtedly extrapolating from the Korean experience, the NSS warns against ignoring “countries determined to develop and proliferate WMD” since doing so typically result in the threats becoming worse and the United States having fewer response options.

The Continuing Resolution enacted by Congress in mid-December provides some additional funding for these counterproliferation, nuclear modernization, and missile defenses programs.

To have a sustained impact, and to get ahead of future proliferation threats, the funding boost must be replicated in the upcoming FY2019 presidential budget request.

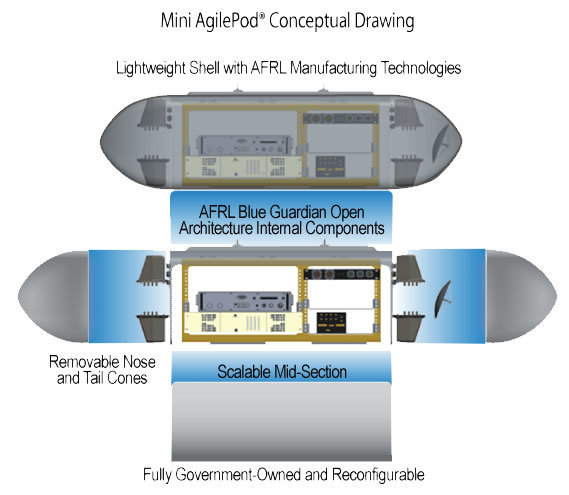

The Mini-AgilePod, conceptualized here, will be designed with an open floor plan and reconfigurable middle sections in various sizes that can be changed depending on specific sensor technologies and missions.

The Mini-AgilePod, conceptualized here, will be designed with an open floor plan and reconfigurable middle sections in various sizes that can be changed depending on specific sensor technologies and missions. President Trump announcing the new national security strategy.

President Trump announcing the new national security strategy.

Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Sunil Lanba with Editor Gulshan Luthra

Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Sunil Lanba with Editor Gulshan Luthra The Navy has invested a lot of time and effort for evaluating various options “through consultations and subject matter experts.

The Navy has invested a lot of time and effort for evaluating various options “through consultations and subject matter experts.