By Robbin Laird

When the CMV-22B Osprey touched down on the deck of USS Carl Vinson in August 2021, it marked more than just another aircraft delivery. It represented a fundamental transformation in how the United States Navy supplies carrier operations. The “Titans” of Fleet Logistics Multi-Mission Squadron (VRM) 30, flying their tiltrotor aircraft, embarked on a journey that would redefine naval logistics and demonstrate unprecedented capabilities in supporting 5th generation carrier aviation across the Indo-Pacific theater.

From 2021 through 2025, VRM-30’s partnership with the Carl Vinson Carrier Strike Group has been characterized by groundbreaking operational milestones, extensive international cooperation, and the successful integration of advanced logistics capabilities that are essential to modern naval warfare. This article reviews that operational history.

The Historic 2021-2022 Deployment

The deployment that began on August 2, 2021, was historic on multiple fronts. USS Carl Vinson departed San Diego as the first carrier to deploy operationally with both the F-35C Lightning II and the CMV-22B Osprey or what the Navy dubbed the “Air Wing of the Future.” For VRM-30, this represented the culmination of years of development, training, and preparation.

The CMV-22B, with a range of 1,150 nautical miles and the ability to carry up to 6,000 pounds of cargo, and an ability to land at night the Osprey exponentially expanded the carrier’s operational tempo. It could transport the F-35C’s F135 engine power module internally, a capability that would prove essential to maintaining the advanced fighter’s operational readiness at sea.

The squadron’s preparation had been meticulous. VRM-30 received its first operational CMV-22B at Naval Air Station North Island, California, in June 2020. Prior to receiving their own aircraft, squadron pilots and maintainers trained extensively with Marine Corps MV-22Bs, building the foundational skills that would be refined aboard the carrier. By November 2020, the Titans had achieved their first carrier landings aboard Carl Vinson off the California coast, demonstrating the aircraft’s compatibility with carrier flight operations.

Once deployed, VRM-30 wasted no time proving the CMV-22B’s worth. In February 2021, during pre-deployment workups, the squadron achieved a crucial milestone by successfully delivering an F-35C power module to Carl Vinson at sea, the Navy’s first such replenishment of this critical component. This capability addressed one of the primary drivers for the CMV-22B’s development: the C-2A Greyhound physically could not fit the larger F-35 engine, creating a potential operational vulnerability for carriers deploying with the advanced fighter.

The same month, VRM-30 participated in another first: the Navy’s inaugural medical evacuation exercise using the CMV-22B aboard an aircraft carrier. On February 22, 2021, the ship’s medical team transported a simulated patient to a Titans Osprey, demonstrating the aircraft’s flexibility beyond pure logistics missions. Lieutenant Andrew Nop, USS Carl Vinson’s nurse, noted that the aircraft provided medical providers with additional options for patient care, particularly for cases requiring rapid transport to advanced medical facilities ashore.

The carrier strike group’s deployment began with participation in Large-Scale Exercise 2021, a live, virtual, and constructive globally-integrated exercise spanning multiple fleets. This massive training event provided VRM-30 with its first opportunity to operate the CMV-22B in a complex, multi-domain combat scenario. The exercise tested modern warfare concepts and allowed the squadron to refine its tactics, techniques, and procedures in a high-tempo operational environment.

For the Titans, LSE 2021 demonstrated the CMV-22B’s ability to sustain carrier operations during extended periods at sea. The aircraft conducted regular carrier onboard delivery missions, maintaining the flow of parts, mail, personnel, and supplies that kept the entire strike group mission-ready. This sustained operational tempo validated the Navy’s decision to deploy three CMV-22Bs per detachment, compared to the typical two C-2A Greyhounds, providing increased flexibility and redundancy.

One of the defining characteristics of VRM-30’s deployments with Carl Vinson has been the extensive cooperation with allied and partner nations. The 2021-2022 deployment featured an unprecedented level of multilateral naval cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region.

In late August 2021, shortly after deployment, Carl Vinson conducted joint interoperability flights with the United Kingdom’s Carrier Strike Group 21, centered on HMS Queen Elizabeth. For the first time, F-35B Lightning IIs from both U.S. Marine Corps and Royal Navy squadrons operated alongside Navy F-35Cs from Carl Vinson, supported by the carrier’s complement of Super Hornets, Growlers, and Hawkeyes. While VRM-30’s primary role remained logistics support, the squadron enabled these complex air operations by ensuring the continuous flow of parts and supplies necessary to maintain such a diverse air wing at peak readiness.

The British cooperation highlighted a crucial aspect of the CMV-22B’s strategic value: its ability to support distributed maritime operations across vast distances. The Osprey’s extended range allowed it to conduct ship-to-ship transfers between American and allied vessels, facilitating the kind of integrated logistics that multilateral operations demand.

On October 3, USS Carl Vinson joined USS Ronald Reagan, HMS Queen Elizabeth, and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s JS Ise in the Philippine Sea for a massive multilateral exercise. The event brought together more than 15,000 sailors from six nations, including ships from the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, New Zealand, and the Netherlands.

For VRM-30, operating in such a dense maritime environment presented unique challenges and opportunities. The squadron coordinated with logistics elements from multiple navies, demonstrating the CMV-22B’s ability to operate seamlessly in a truly joint and combined environment. The exercise validated concepts for distributed maritime operations that would become increasingly important in subsequent deployments.

The partnership with Japan proved particularly significant throughout the deployment. In October 2021, Carl Vinson conducted bilateral operations with the JMSDF’s Izumo-class helicopter destroyer JS Kaga in the South China Sea, the first time Vinson and Japanese forces had operated together in that contested region during the deployment.

These operations included coordinated tactical training between surface and air units, refueling-at-sea evolutions, and maritime strike exercises. VRM-30 supported these activities by maintaining the logistics bridge between Carl Vinson and shore facilities, ensuring the carrier could sustain operations in the South China Sea for extended periods. The squadron’s ability to reach shore bases across the vast Indo-Pacific region proved crucial to maintaining operational tempo far from traditional support infrastructure.

In mid-October, Carl Vinson participated in Maritime Partnership Exercise 2021 alongside naval forces from Australia, Japan, and the United Kingdom in the eastern Indian Ocean. This high-end, multi-domain maritime training exercise focused on advanced capabilities including anti-submarine warfare, air warfare operations, live-fire gunnery, and complex replenishment operations.

The exercise allowed VRM-30 to demonstrate cross-deck flight operations and maritime interdiction support, showcasing the CMV-22B’s versatility beyond traditional carrier onboard delivery missions. The ability to land on various ship classes, combined with the aircraft’s substantial cargo capacity, made it an ideal platform for supporting the diverse requirements of multilateral operations.

The 2024-2025 Deployment: Lessons Applied

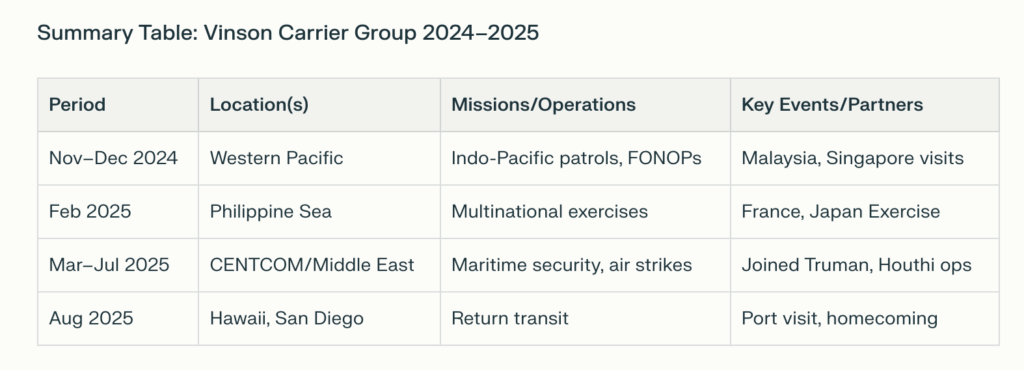

VRM-30’s next major deployment with Carl Vinson began in November 2024 and would prove to be one of the longest and most demanding in recent memory. The carrier strike group departed Naval Air Station North Island on November 18 for what was initially planned as a standard Indo-Pacific deployment. However, global events would transform this deployment into a 269-day marathon that would test both the carrier strike group and its logistics squadron to their limits.

By Christmas 2024, Carl Vinson was operating in the South China Sea, with VRM-30 maintaining the critical logistics lifeline that kept the carrier mission-ready. The squadron’s operations had matured significantly since the 2021 deployment, with established procedures for everything from routine parts delivery to complex cross-deck operations with allied forces.

In February 2025, VRM-30 participated in Exercise Pacific Steller 2025, a week-long French-hosted multilateral large-deck event in the Philippine Sea. This exercise brought together the Carl Vinson Carrier Strike Group, the French carrier strike group centered on FS Charles de Gaulle, and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force’s JS Kaga.

The exercise represented another evolution in VRM-30’s operational capabilities. Working with French naval aviation and JMSDF forces, the Titans demonstrated interoperability across three different naval aviation traditions. The CMV-22B’s ability to operate from shore bases, carrier decks, and even potentially from allied ships showcased the flexibility that modern naval logistics demands.

The Pacific Steller exercise particularly emphasized the CMV-22B’s role in enabling distributed maritime operations, a concept increasingly central to U.S. naval strategy. By providing rapid, long-range logistics support across a widely dispersed force, VRM-30 allowed the three carrier groups to operate as a coordinated but distributed force, making them more difficult to target while maintaining combat effectiveness.

In March 2025, four months into what had been planned as an Indo-Pacific deployment, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth ordered the Carl Vinson Carrier Strike Group to U.S. Central Command. The carrier departed Guam on March 28 and transited through the Malacca Strait, arriving in the Middle East in April to support Operation Rough Rider in response to Houthi attacks in the Red Sea region.

For VRM-30, this sudden shift in operational theater demonstrated the CMV-22B’s strategic flexibility. The squadron maintained carrier operations through the transit and into three months of sustained Middle East operations. While the carrier remained in the North Arabian Sea rather than entering the Red Sea, VRM-30 ensured continuous logistics support, flying missions between the carrier, shore facilities, and support ships to maintain the strike group’s combat readiness.

The extended deployment, ultimately reaching 269 days at sea, placed unprecedented demands on VRM-30’s maintainers and aircrew. The CMV-22B’s reliability and the squadron’s operational expertise proved crucial in sustaining carrier operations far from home port for nearly nine months. When Carl Vinson finally returned to San Diego in August 2025, it was with USS Princeton and USS Sterett, having sailed over 275,000 nautical miles which is a testament to the logistical support that made such an extended deployment possible.

Impact on Naval Operations

VRM-30’s operational history with Carl Vinson has fundamentally demonstrated how the CMV-22B transforms carrier strike group logistics. The aircraft’s combination of helicopter-like vertical takeoff and landing capability with airplane-like speed and range creates operational flexibility that was simply impossible with previous carrier onboard delivery platforms.

The ability to rapidly deliver critical parts from distant shore facilities means carriers can operate farther from traditional logistics hubs while maintaining high readiness rates for their embarked air wings. This is particularly crucial for maintaining F-35C operations, where the aircraft’s advanced systems and unique power module requirements demand responsive logistics support.

Perhaps most significantly, VRM-30’s operations have validated the CMV-22B’s role as an enabler of distributed maritime operations, a concept that envisions naval forces operating across vast areas in a more dispersed formation to complicate adversary targeting while maintaining coordinated combat power.

The Osprey’s 1,150-nautical-mile range allows it to link widely separated naval forces, conducting ship-to-ship transfers, personnel movements, and time-critical parts delivery across distances that would challenge traditional helicopters. This capability has proven essential during multinational exercises where American, Japanese, British, French, and other allied forces operate together across thousands of square miles of ocean.

VRM-30’s extensive operations with foreign naval forces have demonstrated the CMV-22B’s value in combined operations. The aircraft’s ability to operate from allied carriers and support ships, combined with its substantial cargo capacity, makes it an ideal platform for the kind of integrated logistics that modern allied naval operations require.

The squadron’s work with the Japanese, British, French, and other allied forces during multiple exercises has established procedures and relationships that would prove invaluable in any future combined operations. This interoperability extends beyond simple logistics to encompass coordinated operations planning, shared communications protocols, and mutual understanding of capabilities and limitations.

Looking Forward

As VRM-30 continues its partnership with USS Carl Vinson, the lessons learned from these pioneering deployments continue to shape how the Navy employs the CMV-22B. The squadron has proven that the Osprey is not merely a replacement for the C-2A Greyhound, but rather a transformational capability that enables new operational concepts.

The Navy currently plans for a fleet of 44 CMV-22Bs across all VRM squadrons, though some experts argue that effectively supporting distributed operations in a contested environment could require up to 70 aircraft. As VRM-30 and its sister squadrons continue to demonstrate the platform’s capabilities, these discussions about future fleet size will be informed by real operational experience rather than theoretical projections.

From that historic first operational deployment in August 2021 through the grueling 269-day deployment that concluded in August 2025, VRM-30’s partnership with USS Carl Vinson has written a new chapter in naval aviation history. The Titans have demonstrated that the CMV-22B Osprey is not just an aircraft, but a force multiplier that extends carrier strike group reach, enables sustained operations at unprecedented distances, and facilitates the kind of multilateral cooperation that characterizes modern naval operations.

The squadron’s operational history encompasses groundbreaking firsts, from delivering F-35C power modules at sea to conducting complex logistics operations during massive multinational exercises involving forces from across the globe. Through extended deployments that tested equipment and personnel to their limits, VRM-30 has proven the reliability and flexibility that the CMV-22B brings to the fleet.

As the Navy continues to refine concepts for distributed maritime operations and expeditionary advanced base operations, the operational experience gained by VRM-30 aboard Carl Vinson provides the foundation for future employment of this remarkable aircraft. The Titans have not merely adapted to a new platform: they have pioneered new ways of sustaining naval power across the vast expanse of the Indo-Pacific and beyond, ensuring that wherever Carl Vinson sails, the logistical support necessary for mission success follows close behind.

Note: The photos in the slideshow highlight the CMV-22B operating in the Pacific and the CENTCOM area of operations during the 2024-2025 deployment.