By Dr. Richard Weitz

09/04/2011 – An electromagnetic pulse (EMP) is a high-intensity burst of electromagnetic energy caused by the rapid acceleration of charged particles. Once the pulse reaches electronic devices, it disables, damages, or destroys them. An electromagnetic bomb (E-bomb), the deliberate creation of EMP for attacking targets, represents a genuine weapon of mass disruption. Effective use of an EMP could have a devastating effect on the infrastructure of many systems.

At last week’s MAKS 2011 air show, a Russian company unveiled the perfect EMP delivery vehicle: a unique cruise missile system that can be deployed and fired from a standard 40-foot shipping container, from ships, rail cars or even off the back of a truck.

Morinformsystem-Agat JSC is marketing the system as “Pandora’s box.” They claim it can be delivered with the Novator Klub-K 3M-54TE cruise missile. The system can be placed in the self-contained box, along with two crewmembers in a sealed cabin with their communications and targeting systems. The missile can use its inertial guidance system to hit ground targets as far as 270 kilometers away using a high-explosive warhead.

But it could also be used to detonate an EMP weapon above the target.

Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld warned of this “Scud-in-a-bucket” threat in 2004, but the United States has yet to develop sufficient maritime domain awareness to identify and monitor all foreign vessels that operate in the North Atlantic or East Pacific oceans. U.S. air defenses, never very strong, have also deteriorated since the end of the Cold War.

A strong U.S. Coast Guard presence and new combat aircraft based along the U.S. coasts could help reduce the danger of such an attack.

The EMP phenomenon was not evident during the first use of nuclear weapons over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. The two bombs detonated below the necessary altitude to have their EMP reflected by the Earth’s magnetic field, while the electric systems of the B-29 bombers used to release the weapons employed vacuum tubes, which are resistant to EMP flux.

But when the United States began high-altitude testing of nuclear weapons over the Pacific in the early 1960s, the potentially devastating effects of EMP on even distant ground targets attracted widespread attention within the U.S. defense community.

For example, in the 1962 Starfish Prime test, when a nuclear weapon was detonated 400 kilometers (250 miles) above Johnston Island in the Pacific, electrical equipment over 1,400 kilometers (870 miles) away in Hawaii was affected. Streetlights, alarms, circuit breakers and communications equipment all showed signs of distortions and damage. Still, during the Cold War, the United States had other priorities besides worrying about a Soviet EMP attack.

It has only been in the last decade that the U.S. Government has finally engaged in a comprehensive effort to understand better the threat posed by a possible EMP attack against the United States. Most notably, the U.S. Congress established the Commission to Assess the Threat from High Altitude Electromagnetic Pulse (EMP Commission) in 2001.

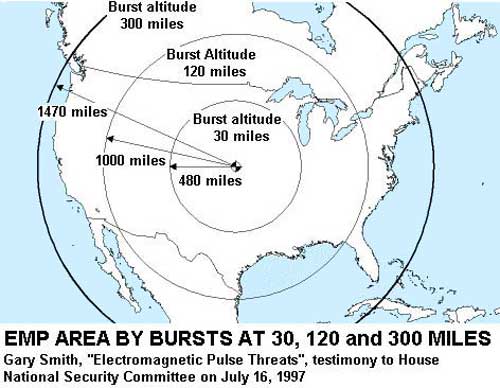

(Credit: http://standeyo.com/NEWS/08_Sci_Tech/081202.EMP.attack.html)

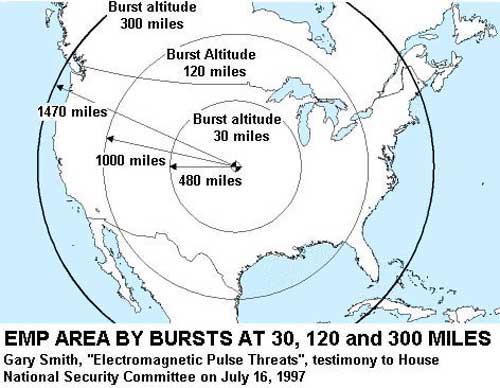

(Credit: http://standeyo.com/NEWS/08_Sci_Tech/081202.EMP.attack.html)

In July 2004, the EMP Commission issued a five-volume report that warned the United States was extremely vulnerable to a catastrophic EMP attack. Indeed, the Commission’s report concluded that, “Our increasing dependence on advanced electronics systems results in the potential for an increased EMP vulnerability of our technologically advanced forces, and if unaddressed makes EMP employment by an adversary an attractive asymmetric option.” The Commission proposed a five-year plan aimed at protecting critical infrastructure from a potential EMP attack, which has never been fully implemented.

The Threat Explained

There are three components to an electromagnetic pulse. The first is the electromagnetic shock that disrupts electronics such as sensors, communications systems, protective systems, computers, and other similar devices. It occurs in less than a billionth of a second and covers the largest distance of the three components.

The middle-time component has a slightly smaller range and is similar in effect to lightening. Although protective measures have long been established for lightning strikes, the potential for damage to critical infrastructure from this component nevertheless exists because it rapidly follows and compounds the first component.

The final component is slower than the previous two, but has a longer duration. It is a pulse that flows through electricity transmission lines – damaging distribution centers and fusing power lines. The combination of the three components can cause irreversible damage to many electronic systems.

An EMP can be generated from natural sources, such as lightning or solar storms interacting with the earth’s atmosphere, ionosphere and magnetic field. It can also be artificially created using a nuclear weapon or a variety of non-nuclear devices. It has long been proven that EMPs can disable electronics, as demonstrated by solar storms, lightning strikes and atmospheric nuclear explosions before the cessation of such tests.

The effect has also been recreated by EMP simulators designed to reproduce the electromagnetic pulse of a nuclear device and study how the phenomenon affects various kinds of electrical and electronic devices such as power grids, telecommunications and computer systems, both civilian and military.

The effects of an EMP — both tactical and strategic — have the potential to be quite significant, but they are also quite uncertain. The precise EMP effects vary depending on many factors. One of the most important variables is altitude. Test data from actual high-altitude nuclear explosions is extremely limited. Only the United States and the Soviet Union conducted atmospheric nuclear tests above 20 kilometers and, combined, they carried out fewer than 20 actual tests.

The most effective altitude is above the visible horizon. If detonation is too low, most of the electromagnetic force from the EMP will be driven into the ground, creating deadly nuclear fallout that deprives the weapon of its non-casualty appeal. Damage is inversely related to the target’s distance from the epicenter of detonation.

In general, the further from the epicenter, the weaker the EMP effects. Yield is another factor to consider. The higher the yield the greater the effect. Even so, since the effects travel through electric lines and waterways, and have secondary spillover impacts on other infrastructure, it is difficult to predict in advance the possible extent of damage from a large-scale EMP attack.

Most vulnerable to an EMP pulse are objects plugged into power grids and commercial computer equipment. Although the EMP is commonly classified as a non-casualty weapon, an EMP detonation would affect vehicle motors, aircraft ignition systems, hospital equipment, pacemakers, communications systems, and electrical appliances. Road and rail signaling, industrial control applications, and other electronic systems are all susceptible to EMP.

Electromagnetic energy on a radio frequency will travel through any conductive matter it comes into contact with—from electrical wires to telephone wires, and even water mains—which can spread the effects to regions outside ground zero.

If an EMP is detonated in orbit, there is a strong potential for substantial damage to U.S. and other satellites as well as any spacecraft in use at the time of the explosion. The military applications of such satellites are critical for defense systems that rely on GPS guidance, such as ballistic missiles and many conventional military strike weapons.

The adverse impact on U.S. space-based communications, early-warning assets, fire control systems, overhead sensors and imagery, and geospatial intelligence would be substantial as well.

The Pearl Harbor analogy is apt here since, under such conditions, potential U.S. adversaries might perceive a clear window of opportunity to pursue their geopolitical ambitions while the United States recovered from such devastation.

Although the altitude necessary for an effective nuclear-based EMP minimizes the likely damage from the nuclear thermal blast and radiation, large numbers of casualties could still occur from the sheer loss of power. Airplanes could fall from the sky, vehicles could stop functioning, and water, sewer, and electrical networks could all fail. Food would rot, health care would suffer, and transportation would become almost non-existent.

The United States and other highly developed nations are especially vulnerable to such attacks given their dependence on extensive transportation networks and other electricity-dependent infrastructures. This insecurity is illustrated by the fact that the average U.S. city only has three days’ worth of food and healthcare provisions.

The August 2003 Northeast Blackout that affected Ohio, New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and parts of Canada demonstrates the potential effects of a wide-area EMP attack. During that incident, over 200 power plants, including several nuclear power plants, were shut down as a result of the electricity cutoff. Loss of water pressure led the local authorities to advise affected communities to boil water before drinking it due to contamination from the failure of sewage systems and other health threats. Many backup generators proved unable to manage the crisis. The initial day of the blackout saw massive traffic jams and gridlock when people tried to get home without traffic lights.

Additional transportation problems arose when railways, airlines, gas stations, and oil refineries also halted operations. Telephone lines were overwhelmed due to the high volume of calls, while many radio and television stations went off-air. Overall, the blackout’s economic cost was between $7 and $10 billion due to food spoilage, lost production, overtime wages, and other related costs inflicted on over one seventh of the U.S. population.

Potential Attackers

Although both Russia and China have the technology to launch EMP attacks, the most plausible attackers against the United States would be those potential U.S. adversaries less dependent on modern technologies and electronics, including both rogue states like Iran and North Korea and stateless terrorist groups.

For these actors, an EMP provides a potential method to attack the United States through asymmetric means. With an EMP, they could circumvent America’s superior conventional military power while being less vulnerable to retaliation in kind.

The Islamic Republic of Iran is developing ballistic missiles that could potentially carry an EMP warhead. If Iran were to develop such a warhead, its existing missile arsenal would allow Tehran to conduct an EMP attack against Israel, U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf, or other neighboring countries.

If under attack or threatened with military action, the Iranian military could also attempt to detonate a nuclear weapon above U.S. warships and other military forces or defense facilities in an attempt to disable their electronics. For over a decade, the Iranian military has rehearsed launching Scud missiles from ships. Some analysts fear that these exercises aim to give the Iranian military the capacity to attack the United States or other potential adversaries with an EMP weapon.

For over a decade, the People’s Democratic of Korea (DPRK) has sought to develop a nuclear warhead as well as a panoply of ballistic missiles, including systems capable of hitting targets in North America. Some analysts fear that Pyongyang might use these assets to attempt an EMP attack against the continental United States.

Although the reliability of North Korea’s longer-range missiles remains uncertain, as does their capacity to carry nuclear warheads, the DPRK military detonated a small nuclear device in October 2006. It has also already perfected the capacity to strike targets in Japan or South Korea with ballistic missiles.

Due to their less sophisticated electronics, DPRK military equipment is less vulnerable to the effects of a nuclear detonation over the Korean Peninsula than South Korean or U.S. forces. Pyongyang has reneged on its commitment to relinquish its existing stock of nuclear weapons in the Six Party Talks aimed at achieving the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. The North Koreans also have a long record of seeking to sell ballistic missile and nuclear weapons technology to other states of proliferation concern.

A successful EMP strike could prevent the U.S. armed forces from organizing a coherent retaliatory strike for some time. Under these conditions, Iranian and DPRK leaders could threaten follow-on attacks unless the United States, its allies, or other targets made major concessions.

Iran and North Korea might also be able to attack U.S. territory directly by launching missiles from a ship located in international waters near the United States. If the attackers scuttled the ship soon after launch, the United States, with many of its intelligence assets blinded, might not be able to identify the perpetrator.