2014-02-02 By Ed Timperlake and Robbin Laird

When President Obama announced a “Pivot to the Pacific,” the focus was really upon the United States and what it was going to do in the period ahead.

But the US is simply part of a very dynamic and fluid defense and security situation in the Pacific.

Much is changing; and little is under the control or direction of the United States. As a senior US commander in the Pacific put it to us in a conversation earlier this year:

“Viewed from Washington the US is either leading a process of allied defense or is facing off in a completion with China. Neither is the core dynamic. The reality is that multiple trends are happening at the same time which are creating a “steam roller effect out here.”

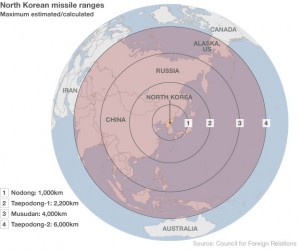

No trend is more significant to Pacific defense than shaping an effective strategy – warfighting and deterrent – against North Korean nuclear weapons and strike missiles.

A key challenge is much thinking around South Korean defense remains rooted in 1954; but this is 2014 and we are dealing with a nuclear power seeking expanded regional reach with his weapons. It is not about preparing to repel the North Korean “legions” coming South.

It is about deterring regional war.

It is useful to put the difference in context by comparing 1954 to 2014.

First, China was a newly independent state under Communist rule moving beyond a brutal Japanese occupation. It was under the leadership of Chou En Lai and Mao Tse Tung and the Korean War would be part of its outreach into the Pacific and statement that an invasion like that of Japan would never happen again.

There is very little relationship between the PRC of 1954 and 2014. The PRC has become a regional power with global reach and is a key player in setting the table for the Second Nuclear Age. And clearly is working to expand its reach and assertiveness into the Pacific. North Korea is both barrier and ally to such an effort.

Second, Japan, Singapore, and Australia are major players in the Pacific and globally. They are building 21st century forces for self-defense and for participation in cross cutting multi-national efforts as well. They are all concerned with potential reach from North Korea into the region, and do not view the Korean defense problem, as a managing the threat from the “hoards” going South. It is about self-defense, and self preservation.

Third, the South Korea of today and 1954 are dramatically different. South Korea could not defend itself in 1954; now it has a very large army and growing arms industry to equip its forces and to export as well.

Fourth, the US and South Korean are in the throes of shifting the command structure in South Korean defense. Although the 2015 deadline for the transfer seems to be a moving, rather than fixed target, clearly the assumption operating with the OPCON is that the US Army will become a supporting command to the ROK Army and that the air role for the Air Forces will NOT follow that example, but with the USAF continuing to play the lead role.

In part, this is due to the realistic focus upon the threat from North Korean aerospace forces, notably missiles and nukes.

In addition to these differences, it is clear that there are a number of key building blocks, which can be leveraged in the period ahead to shape a new strategy.

First, the evolution of missile defense is a key element in any solution set to shape an effective approach. And the trend line here is to more effectively link the disparate systems into a system of systems to more effectively link these defensive systems into a more effective operational whole. This is clearly happening with THAAD and Aegis and needs to happen with regard to the Patriot systems in South Korea as well.

Second, fifth generation aircraft are already available in the region and will be augmented by the shaping of a Pacific fleet of F-35s. The fifth generation aircraft are not simply fighters as Lt. General (retired) Deptula often points out but are forward deployed sensors as well as strike systems. They could be used over time to tee up other strike elements, as well as to integrate with defensive systems to shape a strike and defense enterprise which can deliver a decisive blow to the North Korean nuclear and missile complex if war comes.

Third, the US Navy and USMC are shaping new capabilities for mutli-vector insertion of force, whether it be with the Ospreys, the Bs to come off of the amphibious ships (and with the coming of the USS America) and with the coming of the USS Ford,. Innovative new ways to integrate the air arm into a comprehensive strike and defense complex.

Clearly, a 21st century Inchon strategy is possible with the evolution of US Air Force, US Navy and USMC capabilities combined with evolving US Army ADA capabilities as well.

A key issue to address is the question of the use of nuclear weapons themselves. The Russians have made it clear that the modernization of their tactical nuclear arsenal is part of their response to the Second Nuclear Age and their defense of the Russian Far East, a region crucial to their future.

Assuming the United States does not want to go down that path, there will need to be a concerted effort to build out the strike and defense capabilities to ensure the credibility of a nuclear dismantlement, missile destruction and leadership decapitation strategy. Not accepting the “hoard goes South” as the initial feint followed by the Dear Leader determining when to strike is central to an effective strategy.

Hunkering down to defend and focusing on eliminating an artillery tube belt as a primary mission simply misses the point of the changes since 1954.

Clearly, there are a number of regional stakeholders in the evolution of South Korean defense strategy. Despite the tensions in the region and the historical rivalries, a North Korea unleashed is not in the interest of Russia, Japan, Australia or Singapore to mention simply the most obvious players.

And in the case of Japan, the key question will clearly be: If the US does NOT have a credible deterrent strategy against North Korean nukes, how do I build one?”

This is not an option in a wargame or on briefing slides.

This about the only country in the world with real experience with the consequences of nuclear war, not wishing to repeat the experience.

This is not a think tank exercise; it is a real world pressure point.

Another aspect to consider is shaping the future of US forces in the region.

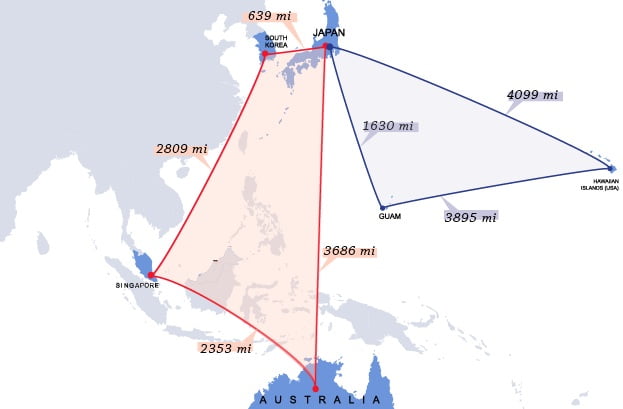

In our book with Richard Weitz on crafting a 21st century strategy in the Pacific we highlighted the importance of what we called the strategic quadrangle.

Rather than focusing simply on the image of projecting power forward, what is crucial to an successful Pacific strategy is enabling a strategic quadrangle in the Western Pacific, anchored on Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Singapore.

This will not be simple. Competition, even mutual suspicion, among US allies in the Western Pacific is historically deep-rooted; as a former 7th USAF commander underscored, “history still matters in impeding allied cooperation.”

But in spite of these challenges and impediments, enabling the quadrangle to do a better job of defending itself and shaping interoperability across separate nations has to become a central strategic American goal.

From this perspective, the focus is upon shaping more capability for the US and its allies to operate collectively and cohesively from the area of strategic quadrangle to deal with threats in the region, whether from the PRC, the North Koreans, pirates or whomever.

We are not going to have the luxury of a force for Korea, a force for Japan, a force for Australia, a force for the straits of Malacca, etc.

The reality is that it will be a joint and coalition force able to deal with a diversity of threats from the standpoint of strategic advantage.

For the United States, this clearly means leveraging air and naval power in innovative ways within which the US Army and its contribution is integrated and not the other way around.

In other words, it is about leveraging technology but to reshape concepts of operations and organizational structures to unleash further developments in technology to ensure the future capabilities of American joint force.

We clearly are at a crossroads.

And with all crossroads, there is no guarantee, we will take the most effective path.

Also see the following related pieces:

http://www.sldforum.com/2014/02/shaping-deterrent-strategy-todays-north-korea/

https://www.sldinfo.com/getting-the-us-armys-future-right-critiquing-a-tradoc-perspective/