01/03/2012 – by Dr. Scott Truver

The focal point of U.S. Coast Guard acquisition reform and recapitalization remains the National Security Cutter.

The NSC is one of the Coast Guard’s major contributions to the nation’s fleet. As such, the Navy may want to look at the Legend-class cutters as a cost-effective means to carry out “lower end,” yet critical roles and missions, and as a complement to its Littoral Combat Ships.

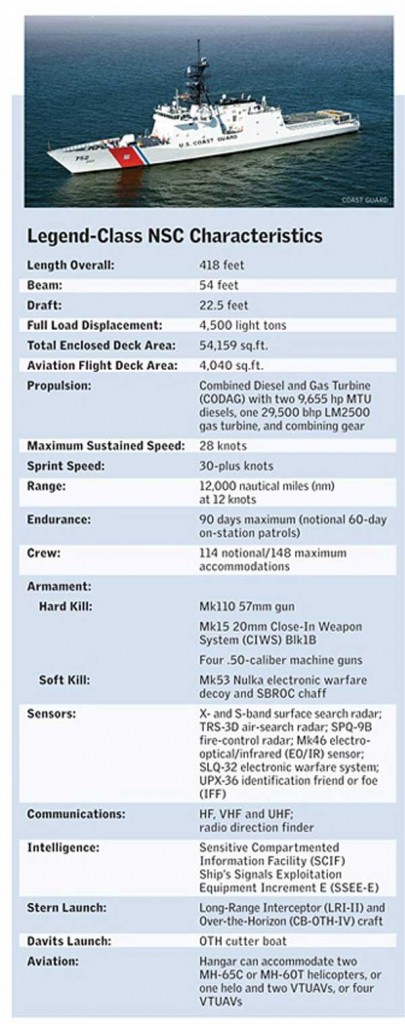

Unlike the 45-plus knot Littoral Combat Ship, the NSC has been optimized for higher speeds and significant endurance. Compared to the Hamilton-class 378s they are replacing, the 418-foot NSC design provides better seakeeping and higher sustained transit speeds of 28 knots, or 30-plus knots sprint speed; greater endurance and range with maximum 90-day patrols and 12,000 nautical miles at 12 knots; an improved ability to launch and recover small boats, helicopters and drones; and advanced secure command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems (C4ISR) and ability to handle sensitive information.

That said, budgets will remain squeaky-tight for years, if not longer, and dynamics completely out of the Coast Guard’s control could derail even the best of plans.

The first three cutters were procured through the Deepwater Integrated Coast Guard Systems consortium under cost-plus incentive-fee contracts. NSC numbers four and five are being procured through Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Ingalls Shipbuilding in Pascagoula, Miss., under fixed-price incentive-firm contracts.

As of late 2011, the total costs of the NSC ships were: $591 million for the Bertholf, which included design costs; $432 million for the Waesche; $467 million for Stratton; and $480 million for Hamilton. The Coast Guard in September signed a contract for a fifth unnamed ship for $482 million. Three of the cutters — Bertholf, Waesche and Stratton — were sailing by the end of November. Plans call for the remaining three NSCs to be delivered by 2019.

The Office of Management and Budget has approved a capital investment plan for the next five years that shows numbers six, seven and eight in the program.

“I’m optimistic that we will get it done,” Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Robert Papp Jr. noted in a National Defense interview. “We need to get it done and I’m committed to getting those eight ships built.”

Shipyard innovations and learning-curve efficiencies contributed to the $180 million reduction in the cost of the second ship compared to the lead cutter. Costs increased for Stratton and Hamilton, however, which was largely the result of structural enhancements to improve fatigue life, for which Bertholf and Waesche will be retrofitted in the future. And, a 3-year delay between the third and fourth NSCs also contributed to an increase in costs for Hamilton.

The $482 million contract the Coast Guard signed for the fifth national security cutter is only $2 million more than Hamilton cost.

The first two NSCs were found to be remarkably “clean” during their builders’ and acceptance trials, thus reducing the need for expensive “fix-its.” Although the Navy’s Board of Inspection and Survey (INSURV) identified some problems, it concluded that Bertholf is a “unique and very capable platform with great potential for future service.”

More important, the service and shipyard capitalized on lessons learned from Bertholf during construction of Waesche and in November 2009 took delivery of a cutter that had a significantly higher level of quality and completeness than the lead ship. INSURV reported Waesche is a “very clean and capable platform” that met or exceeded all readiness expectations.

“We continue to build on lessons learned and made significant improvements to the Stratton, including hull-strengthening, construction process efficiencies, enhanced functionality and improved sequencing,” Mike Duthu, NSC program manager at Ingalls Shipbuilding division, said in an interview. “There is an intense focus on achieving lessons learned, and we constantly ask ourselves: How can we do this better and more efficiently? This process involved all divisions of the yard and every functional department — operations, engineering, planning and material experts.”

As a result, Stratton was delivered in September with 31 percent fewer INSURV-noted discrepancies than Waesche.

One of the most notable process improvements has been the significant reduction in the number of “grand blocks” — multiple units stacked together in large assembly halls away from the waterfront — used to put together the ship’s hull. Entire sections of the NSC are built and outfitted on shore, out of the weather, and then lifted into place, allowing for earlier outfitting completion and testing, and resulting in a significant reduction in wait times. Time is money.

“We used 32 grand block lifts to assemble Bertholf and 29 lifts for Waesche, but needed only 14 to assemble Stratton,” Duthu said. “This enabled more sub-assembly work in each grand block in a controlled environment and led to fewer construction hours compared to the process for Bertholf.”

Also, the design has remained remarkably stable since the reviews of 2002-2004. “The shipyard benefitted from mission/requirements stability,” Duthu said. “There was not much ‘churn’ in requirements, although the post-9/11 environment did see some new requirements.”

Those included collective protection system for chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear protection and the sensitive information facility in Bertholf and the following ships. Concerns about hull strength drove a design change in the third NSC, he said.

“That’s a good thing from the yard’s perspective, as we can take advantage of the efficiencies associated with a stable design,” Duthu said.

Acquisition stability is also critical, as it allows the yard to get closer to a “heel-to-toe” production schedule — ideally a new ship award every year. That wasn’t the case for the first three ships, but the contract for the fourth came with an option for number five, Duthu noted.

The Coast Guard’s acquisition practice of awarding one cutter every several years works against achieving efficiencies from serial production and materials buys. It is unlikely the program will have a multi-year procurement for the final three cutters, which would require congressional authorization. But, if the program is expanded beyond eight ships, for other U.S. and foreign customers, that might be a cost-saving option to consider.

“We’d be able to leverage everything — stable workload, stable funding and a stable product funded at consistent and constant intervals — to wring even more efficiencies out of the program,” Duthu offered. “But without such stability, it’s unlikely that the cost can come down much more than it already has.”

The cutters’ roots are in the ill-fated and now-defunct Integrated Deepwater Systems program, which included three classes of cutters and other boats, new manned patrol aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles, and leading-edge off-the-shelf C4ISR systems.

As early as 2001, Deepwater had come under increasing scrutiny and criticism from Congress, the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Homeland Security’s inspector general, and sundry official and unofficial observers. Among other challenges, the GAO identified serious management, funding, cost, schedule, design and technical shortcomings in several Deepwater “asset classes.” A new July report noted the program “continues to exceed the cost and schedule baselines approved … in 2007.”

The upshot of these challenges was the dismissal of the Integrated Coast Guard Systems lead systems integrator, a joint venture of Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin. Now, a revamped Coast Guard acquisition directorate oversees the $25 billion program, which still looks to recapitalize the Coast Guard for the 21st century.

“We have instituted acquisition reforms now that I think serve as a model for other organizations across government,” Papp testified in March before the House Homeland Security committee’s transportation and infrastructure subcommittee.

“There is a sense of urgency to get on with recapitalizing the Coast Guard,” Capt. Peter Oittinen, the Legend-class program manager in the service’s acquisition directorate, said in an interview. “The eight NSCs are replacing the 12 increasingly obsolescent and costly-to-maintain 378-foot Hamilton-class high-endurance cutters that have been in service since the 1960s.”

“Eight NSCs might not be enough,” said Capt. Kelly Hatfield, commanding officer of the cutter Waesche.

There are indications that the service would gladly accept another two or three or more NSCs, should the resources be available, particularly if other components of the service-wide recapitalization program do not materialize.

The NSCs are also ideal for the growing maritime security/constabulary tasks under the National Fleet Policy calling for Navy and Coast Guard forces to partner. There are direct commonalities with the Freedom and Independence classes of Littoral Combat Ships and even the Arleigh Burke (DDG 51) guided-missile destroyers.

“The NSCs were designed and engineered with two competing attributes,” Hatfield noted. “They are multi-mission ships that have long endurance but can go fast.”

Posted with the permission of National Defense (http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/archive/2012/January/Pages/CoastGuardStakesItsFutureonNationalSecurityCutters.aspx)

For our special report on the National Security Cutters see https://sldinfo.com/national-security-cutter-special-report/.