By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

The F-35 and its ability to work with, to leverage and to enhance the capability of the power projection forces is at the heart of the next 20 years of rebuilding U.S. and allied forces.

It is clear that a fundamental reconstruction is required with the “geriatric condition” of U.S. forces and the past ten years of ground combat in a far away area with an adversary who could not threaten U.S. combat aircraft.

Yet much of the discussion inside the Beltway treats this plane as if it were simply a tactical aircraft replacement for the USAF, USN and USMC fleets. It is really a “flying combat system”, rather than a tactical aircraft, which allows the US and its allies to look at power projection in a very different way. And it allows the U.S. and its allies to get best value out of their forces.

The F-35 is called a joint strike fighter. And it is just that.

The plane will replace multiple aircraft in the fleet, and by so doing create significant economies of scale and savings. The aircraft is 80% common across the fleet and savings come from software commonality, new approaches to digital maintenance, and flight line enhancements and improvements.

Possibly the most important capability this aircraft has is the ability to combine information it has with Aegis systems and other command and control systems operated by allies worldwide. This sharing capability will not just enhance combat capability, but to change dramatically the way the U.S. can work with its allies.

The article will discuss several aspects of the change, which is disruptive in nature. If the culture of thinking about combat does not change, and one thinks of this as the next iteration of what the services will have for combat aircraft, the entire revolution will be missed.

Interview with First “Regular” F-35 Pilot from SldInfo.com on Vimeo.

Anticipating the Re-Norming Revolution: The USAF, the F-22 and the F-35

The F-22 has been deployed for several years and its evolution is having a significant impact on rethinking air operations. The decade or more of deployment prior to F-35 will provide a significant impact on the F-35 and its concept of operations.

The primary task of the F-22 is air-to-air dominance followed by core competence in counter-air defense missions. The F-22 also provides a key gap-filler capability between the now-retired F-117 and the exceptional capabilities of the F-35 against increasingly lethal mobile air defense systems.

For example, the SA-10s and SA-20s can be dismantled, moved and ready for action in a very short period of time. The trend line is towards rapid mobility in the adversary’s air defenses, and mobility in this domain means that the incoming strike aircraft must be able to do target identification, target acquisition and strike missions virtually simultaneously.

A key aspect of the new fifth generation aircraft is its machine processing capability on-board, which allows the pilot to do simultaneously operations, which historically required several platforms operating sequentially.

But the limited numbers of the F-22 will ensure that the F-35 will be the dominant 5th generation aircraft both in terms of numbers and availability in a coalition environment. From the standpoint of thinking through 21st century air operations, the ability of the F-22 and F-35 to work together and to lead a strike force will be central to U.S. core capabilities for projecting power and will be a central role of the 21st century USAF.

For the USAF, the largest stakeholder in F-35, the challenge and opportunity is to blend the F-22s with the F-35s in creating a “re-normed” concept of air operations.

For example, the F-22 and F-35 will work together in supporting air dominance, kick in the door, and support for the insertion of a joint power projection force. Here the F-22 largely provides the initial strike and guides the initial air dominance operations; F-35 supports the effort, with stealth and sensor capabilities, able to operate in a distributed network to provide strike and ISR and capabilities to suppress enemy air defenses as well attack shore defenses against maritime projection forces.

4th generation aircraft join the fray as areas of the battlefield are cleared of the most lethal threat systems, expediting participation and increasing survivability by linking into the 5th generation networked Situational Awareness.

An excellent insight into the role of the F-22 in anticipating the F-35 has been provided by a USMC pilot of the F-22.

Lt. Col. “Chip” Berke has become a key F-35 squadron commander at Eglin AFB but provided an interview while at Nellis AFB with regard to his experience with the F-22 and how he saw the F-22 as part of the ongoing revolution in “re-norming” air operations.

In response to a question about what the fused sensor experience is all about in the fifth generation aircraft and how the whole capability of an aircraft is not really an F series but a flying combat system, Berke provided the following explanation.

I think you’re hitting the nail on the head with what the JSF is going to do, but it’s also what the Raptor mission have already morphed into. The concept of Raptor employment covers two basic concepts. You’ve got an anti-access/global strike mission; and you have the integration mission as well. And the bottom line is that integration mission is our bread and butter. When I say “us,” I’m talking about the Air Force and the F-22. Most of our expected operating environments are going to be integrated….

And as a pilot with significant operational experience across the legacy fleet, Lt. Col. Berke provided insight into how the 5th generation solution was different.

It’s a major evolution. There’s no question about it. My career has been in F-18s, but I also flew F-16s for three years. I was dual operational in the Hornet and the Viper when I was a TOPGUN instructor. I am now coming up on three years flying Raptors. I was also on carriers for four years, so I’ve done a lot of integration with the Navy and a lot of integration with the Air Force. Three years flying with the Air Force has been pretty broadening.

For me, it’s a great experience to see the similarities and difference between the services. Navy and Marine aviation is very similar. USAF aviation is very different in some ways. I actually was with the Army for a year as FAC in Iraq as well. So from a tactical level, I’ve got a lot of tactical operator experience with all three services – Navy, Army, and the Air Force. This has been really illuminating for me having the experience with all of the services in tactical operations. Obviously I will draw upon that experience when I fully engage with the JSF. But flying a Raptor, the left, right, up, down, is just flying; flying is flying. So getting in an airplane and flying around really is not that cosmic no matter what type of airplane you’re sitting in.

But the difference between a Hornet or a Viper and the Raptor isn’t just the way you turn or which way you move the jet or what is the best way to attack a particular problem. The difference is how you think. You work totally differently to garner situational awareness and make decisions; it’s all different in the F-22. With the F-22 and certainly it will be the case with the F-35, you’re operating at a level where you perform several functions of classic air battle management and that’s a whole different experience and a different kind of training…..

In the Raptor, the data is already fused into information thereby providing the situational awareness (SA). SA is extremely high in the F-22 and obviously will be in the JSF; and it’s very easy for the pilot to process the SA.

Indeed, the processing of data is the key to having high SA and the key to making smart decisions. There’s virtually no data in the F-22 that you have to process; it’s almost all information.

USAF pilots have underscored some of the changes articulated by “Chip” Berke and have re-enforced the need for culture change to get a very different air combat and overall combat capability into the U.S. 21st century force structure.

An interview with three senior USAF pilots at Langley AFB in late 2010 underscored the significance of the change. The three pilots—Lt. Col Damon Anthony, Maj. James Akers and Lt. Col Steve Pieper—provided an understanding of how classic combat operations built around the use of AWACS and the CAOC will be modified as new aircraft re-shape operational capabilities.

As “Rowdy” Pieper put it:

I think the most difficult and the most painful set of shifts will be organizational. They will relate to the people who are now forced to relinquish operational strategic decisions to folks like us in the room. Which has always been the case.

So tactical decisions have always had operational strategic and national impact. The difference is that organizationally, we’ll be forced to reconcile that notion, and understand that the individual who’s charged with those tactical decisions will now have the kind of information that was previously only available nearly fused but far more imperfectly fused in the CAOC. That information will now be distributed in the battlespace.

So that speaks to an entirely different — not just physical architecture, also personnel architecture, but more importantly leadership paradigm and approach to solving a problem. You now are far more able to remove fat layers of intermediate data processing and you’re able to sic a force of very capable assets on an objective.

We’re able dynamically to adapt in the middle of that process and make appropriate decisions in support of your objective far more effectively than if you had just sent planes out on a specific task.

In other words, the F-22 has paved the way for the F-35 and integrating the F-22 with the F-35 will be a core contribution of the USAF in shaping innovative combat capabilities for the US and its allies in the decade ahead.

Neither the F-22 nor the F-35 are simply new fighters; they are shapers of an entirely new approach to combat capabilities across the joint and coalition force.

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is often defined by its stealth characteristics, and the debate revolves around whether one needs “a high end aircraft” or, if one is negative, whether “stealth is really stealthy.” Although interesting, such a discussion really misses the point.

Stealth is an enabler for this aircraft, not its central definition.

As a USMC F-18 pilot put it:

I would say low observability is a capability set or is an asset to the platform, but the platform as a whole brings a lot by itself. There are situations where low observability will be very important to the mission set that you’re operating in. And then there will be situations where the ISR package or the imaging package that comes with that aircraft, the ability to see things, will be more important; that will change based on the mission set and how you define the mission.

And one of the challenges facing the F-35 is that historical aviation words are used which obscures the technological advance which stealth has on the aircraft itself.

As Lt. General (Retired) Deptula constantly reminded the USAF and others, the F before the F-22 and the F-35 is somewhat of a misnomer. They are really significant generational changes in the way individual combat aircraft and fleets of aircraft handle data and can make decisions.

Stealth on this aircraft is a function of the manufacturing process; it is not hand built into the aircraft and maintained as such. It is a characteristic of high tolerance manufacturing, and as such stealth will be maintained in the field not done in the factory or depot. This is revolutionary in character.

(For a comprehensive look at the key elements of the F-35 see our Special Report on the F-35).

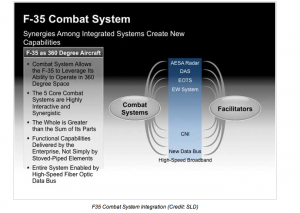

At the heart of the F-35 is a new comprehensive combat systems enterprise.

The F-35 is the first combat aircraft, which sees completely around itself.

The Distributed Aperture System is what allows this to happen; and allows the operator or the fleet managers to see hundreds of miles away on a 360-degree basis. And the combat system enterprise allows the aircraft to manage the battlespace within this 360-degree space.

Unlike legacy aircraft which add systems which have to be managed by the pilot, the F-35 creates a synergy workspace where the core combat systems work interactively to create functional outcomes; so for example, jamming can be performed by the overall systems, not just by a dedicated electronic warfare system.

The F-35 in many ways is a flying combat system integrator and in a different historical epoch than F-15s, F-18s and F-16s. The 360 degree capability coupled with the combat system enterprise explains these historic differences on a per plane basis; the ability of the new aircraft to shape distributed air operations collectively is another historic change, one which the U.S. and its allies need to make with the growing missile, air defense and offensive air capabilities in the global market space and battlespace.

The legacy combat aircraft have added on new combat subsystems over 30 years., These evolved aircraft and their new subsystems are additive, iterative and sequential. The resulting configurations are built over the core foundational aircraft designed and fielded as long as more than 30 years ago.

All of the legacy U.S. aircraft with the latest modifications when offered for foreign sale were rejected in the Indian fighter competition for the much newer European fighters, the Eurofighter and Rafale.

The F-35 was built from a clean sheet, with a foundation that allows interactivity across the combat systems, allowing the forging of a combat system enterprise managing by the computer on the aircraft.

Said another way, the F-35’s core combat systems are interactive with one another creating a synergistic outcome and capability, rather simply provided an additive-segmented tool. The aircraft’s systems are built upon a physical link, namely a high-speed data bus built upon high-speed fiber optical systems.

To provide a rough comparison, legacy aircraft are communicating over a dial up modem compared to the F-35 system, which is equivalent to a high-speed broadband system. The new data bus and the high speed broadband are the facilitators of this fully integrated data sharing environment on board the aircraft. While legacy aircraft have had similar subsystems, integration was far less mature.

Connected to the other combat systems via the high-speed data bus is the CNI system (Communications, Navigation and Identification). This is a very flexible RF system which enables the aircraft to operate against a variety of threats. The other core combat systems, which interact to create the combat systems enterprise, are the AESA radar, the DAS, the Electrical Optical Targeting System (EOTS) and the Electronic Warfare system.

As “Toes” Bartos, former Strike Eagle Pilot and now with Northrop Grumman has put it:

When this plane was designed, the avionics suite from the ground up, the designers looked at the different elements that can be mutually supporting as one of the integration tenets. For example, the radar didn’t have to do everything; the Electrical Optical Targeting System (EOTS) didn’t have to do everything. And they were designed together.

Fusion is the way to leverage the other sensor’s strengths. To make up for any weaknesses, perhaps in the field of regard or a certain mode, a certain spectrum, with each of the sensor building block, they were all designed to be multifunction avionics.

For example, the AESA, advanced electronically scanned array is a MFA, a multi-function array. It has, of course, the standard air-to-air modes, the standard air-to-ground modes. But in addition, it’s really built from the ground up to be an EW aperture for electronic protection, electronic support, which is sensing, passive ops, and electronic attack.”

(For our look at the F-35 combat systems enterprise as part of military space see our Space News op ed published on June 25, 2012).

A way to look at the cross-functionality of the combat systems is simply to think past the narrow focus of additive systems. A system is added to do a task. The pilot now needs to use that system to manage the task. With the F-35 interactive systems, the pilot will perform a function without caring which system is actually executing the mission.

For example, for electronic warfare, including cyber, he could be using the ETOPS, the EW system or the AESA radar. The pilot really does not care, and the interactivity among the systems creates a future evolution whereby synergy among the systems creates new options and possibilities. And of course, the system rests on an upgradable computer with chip replacement allowing generational leaps in computational power.

This fusion engine is at the heart of the evolution over time of the F-35.

General Robling, the recent Deputy Commandant of USMC Aviation and now senior US Marine in the Pacific, was asked by a journalist at the Paris Air Show in 2011: “What is the next great airplane after the F-35 and the Osprey?”

Robling’s answer was something like this: “Every few years the F-35B will be more capable and a different aircraft. The F-35B flying in 2030 will be significantly more capable than the initial F-35Bs. The problem is that will look the same at the airshows; but will be completely different inside. So you guys are going to have a tough time to describe the differences. It is no longer about adding new core platforms; it is about enabling our core multi-mission platforms. It is a very different approach.”

The key difference with the legacy aircraft is the legacy system is an additive structure, more like a cell phone than a smart phone with many applications available to the pilot.

With the F-35, one is building a flexible architecture that allows one to operate like a smart phone.

With the F-35, you’re defining a synergy space within which to draw upon your menu of applications. And the F-35 combat systems are built to permit an open-ended growing capability. In mathematical analogies, one is describing something that can create battlespace fractals, notably with a joint force able to execute distributed operations.

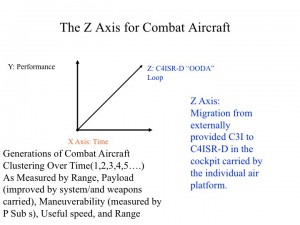

The aircraft is itself just a facilitator of a much more robust combat environment that was available with legacy aircraft and command and control. This change requires the pilots themselves to rethink how to operate. Performance of this aircraft and its pilot allows a revolution along the information axis of combat or what might be identified as the “Z Axis.”

Operating on the Z Axis: Shaping a New Pilot Culture

The design characteristics blended together prior to F-35 have been constantly improving range, payload (improved by system/and weapons carried), maneuverability (measured by P Sub s), useful speed, and range (modified by VSTOL–a plus factor).

The F-35 is also designed with inherent survivability factors; first, redundancy and hardening and then stealth. Stealth is usually seen as the 5th Gen improvement. But reducing the F-35 to a linear x-y axis improvement or to stealth simply misses the point. The F-35 is now going to take technology into a revolutionary three-dimensional situational awareness capability.

This capability establishes a new vector for TacAir aircraft design.

This can be measured on a “Z” axis.

Traditionally, the two dimensional depiction is that the x-axis is time and the y-axis is performance and captures individual airplanes that tend to cluster in generation improvement. Each aircraft clustered in a “generation” is a combination of improvements. Essentially, the aeronautical design “art” of blending together ever improving and evolving technology eventually creates improvements in a linear fashion.

The F-35 is not a linear performance enhancement over legacy or fourth generation fighter aircraft. When one considers information and the speed at which it can be collected, fused, presented and acted upon in the combat environment, those who possess this advanced decision capability will be clearly advantaged.

While this is not a new concept having been originally conceived in the famous Boyd “OODA” loop, the information dimension of combat aircraft design now is so important that it forces us to gauge the value of such a weapon system along a third dimension, the “Z” axis.

The Z axis is the pilot’s cockpit “OODA” loop axis or his ability to observe, orient, decide and act. This ability is measured as the combined capability the pilot gains from integrated command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance and his resultant decision-making and employment or action.

From Boyd’s theory, we know that victory in the air or for that matter anywhere in combat is dependent on the speed and accuracy of the combatant to make a decision. The better supported the pilot in a combat aircraft is by his information systems, the better the combat engagement outcome. The advantage goes to the better information enabled. Pilots have always known this was true but the revolutionary advancement 5th Generation, designed in C4ISR-D requires a similar advancement in how pilots approach their work.

In addition, today‘s industrial learning curve to improve sensors, system capability and weapons carried is likely flatter than that required to build another airframe and may be a new American way of industrial surging. The American arsenal of democracy may be shifting from an industrial production line to a clean room and a computer lab as key shapers of competitive advantage. This progress can be best seen in movement out the Z-axis.

The USAF F-22 pilot community has been experiencing this revolution for some time and their lessons learned are being incorporated into the F-35 training. Learning from those experiences as well as those of the legacy fleet, the USMC recognizes that a new pilot culture will emerge because of operating on the Z axis.

General “Dog” Davis, former 2nd MAW commander and now Deputy Cybercom Commander, underscored that three pilot cultures are being rolled into a very new one. The 2nd MAW commander linked this to generational change.

The F-35B is going to provide the USMC aviator cultures in our Harriers, Hornets and Prowlers to coalesce and I think to shape an innovative new launch point for the USMC aviation community. We are going to blend three outstanding communities. Each community has a slightly different approach to problem solving. You’ve got the expeditionary basing that the Harrier guys are bringing to you. You have the electronic warfare side of the equation and the high-end fight that the Prowler guys thing about and the comms and jamming side of the equation, which the Prowler guys think about. And you have the multi-role approach of the F-18 guys…..

What General Davis discussed concerning the new pilot culture is shaped in large part by bringing EW into the cockpit. The Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron 1 (MAWTS) are currently

MAWTS pilots and trainers are looking at the impact of V-22 and F-35 on the changes in tactics and training generated by the new aircraft. MAWTS is taking a much older curriculum and adjusting it to the realities of the impact of the V-22 and the anticipated impacts of the F-35.

MAWTS is highly interactive with the various centers of excellence in shaping F-35 transition such as Nellis AFB, Eglin AFB, the Navy/Marine test community at Pax River Md, and with the United Kingdom. In fact, the advantage of having a common fleet will be to provide for significant advances in cross-service training and con-ops evolutions.

Additionally, the fact MAWTS is studying the way the USAF train’s combat pilots to be effective flying the F-16 in shaping the Marine F-35B Training and Readiness Manual (T&R Manual) is a testimony to a joint service approach. This is all extremely important in how MAWTS is addressing the future. An emerging approach may well be to take functions and then to redesign the curriculum around those functions.

For example, the inherent capabilities of the emerging F-35 C4ISR-D cockpit with 360 degree situational awareness may turn out with appropriately designed data links to be a force multiplier in the tactical employment of the MV-22 Osprey and the Helicopter community and reach back to Navy combat forces afloat.

Northern Edge 2011: Leveraging Real World Exercises for Operational Testing

The F-35 can indeed be understood as a combat aircraft which can operate in 360 degree space for more than 800 miles out and able to manage the combat space within its 360 degree radius.

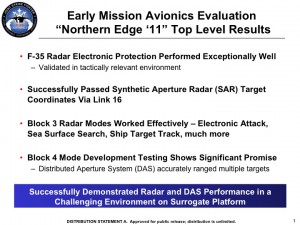

A recent operational test of the F-35 radar and the distributed aperture system (DAS) occurred in Northern Edge 2011 a joint and combined exercise that serves as a focal point for the restructuring of U.S. power projection forces.

As the results from the exercise are evaluated, military leadership and program managers should be able to make a definitive judgment on the way ahead for the program now, not in some distant future.

In both Northern Edge 2009 and 2011, the air combat baseline was being re-normed and the limitations of legacy aircraft well highlighted when compared to newer systems. Northern Edge validated, in real time, the ability of American and soon allied TacAir fleets to give total concurrent situational awareness to each combat pilot.

In a robust jamming operating environment, the F-35 radar and DAS separated themselves from the pack, and have initiated a new era in thinking in combat operations.

As a F-35 Joint Program Office release underscores this is not only about the ability of airpower to operate in a robust EW environment in which cyber conflict is a key dimension but it is about the ability of an airborne capability to support maritime operations.

This year provided an invaluable opportunity to observe the performance of the F-35 JSF systems in multiple robust electronic warfare scenarios. The AN/APG-81 active electronically scanned array radar (AESA) and AN/AAQ-37 distributed aperture system (DAS) were mounted aboard Northrop Grumman’s BAC 1-11 test aircraft. Making its debut, the AN/AAQ-37 DAS demonstrated spherical situational awareness and target tracking capabilities. The DAS is designed to simultaneously track multiple aircraft in every direction, which has never been seen in an air combat environment.

A return participant, the AN/APG-81 AESA demonstrated robust electronic protection, electronic attack, passive maritime and experimental modes, and data-linked air and surface tracks to improve legacy fighter situational awareness. It also searched the entire 50,000 square- mile Gulf of Alaska operating area for surface vessels, and accurately detected and tracked them in minimal time…..

The C4ISR-D capability in each cockpit takes the F-35 out of the linear 5th Gen development path.

The F-35 radar was validated in a tactically relevant environment. Until proven otherwise America is still has the most capable EW and to use an older phrase ECCM (Electronic Counter Counter Measures) fighting force in the world. So being tactically “validated” in an American designed exercise is the gold standard.

Northern Edge exercises provide operational, not test, environments. Block 2 is ready for Marine F-35B IOC. Block 2 was the first improvement up the Z-axis-in 2009 and pilots from the Marine Air Weapons Training Squadron, MAWTS (Marine equivalent of “Top Gun”) are paying close attention. Block 3 — the next step up the Z-axis–demonstrated that the radar worked effectively in sea surface search and ship target track.

If American TacAir forces afloat can see an enemy they will kill that enemy. Block 4 is the next step up for “3 Dimensional Warriors” and a “Z-Axis” cockpit. A fighter pilot very familiar with Northern Edge when asked about DAS said it had a feature of “Passive Ranging.” When asked what that meant he casually remarked: “Shooting people off your tail and all that stuff.”

Operating Differently: A Peek into the Future

Rediscovered off of the shores of Tripoli is what the Amphibious Ready Group or ARG or what we prefer to call the Agile Response Group can do with transformational aircraft.

The aircraft in this case was the Osprey, but the Osprey paired with the F-35B will make the Gator navy not just a troop carrier but a capital ship. It is harder to find a greater value proposition than adding the F-35B to the fleet and turning amphib tigers into air combat lions.

The ARG is in the throes of fundamental change, with new ships and new planes providing new capabilities.

These new capabilities are nicely congruent with the Libyan operational experiences. Given the Marines battle hymn, it seems that “off the shores of Tripoli” can have a whole new meaning for the evolution of the US force structure.

The ARG was used in several unprecedented ways in the Libyan operation. First, the V-22 Osprey was a key element of changing how U.S. forces operated. The Osprey provided a logistical linchpin, which allowed the ARG to stay on station, and allowed the Harriers to generate greater sortie generation rates and ops tempo.

The use of the Osprey in the operation underscored the game changing possibilities of the ARG in littoral operations of the future.

The key point here is that the sea base, which in effect the ARG is, can provide a very flexible strike package. Given their proximity to shore, the Harriers could operate with significant sortie rates against enemy forces.

Not only could the Harriers come and go rapidly, but also the information they obtained with their Litening pods could be delivered to the ship and be processed and used to inform the next strike package. Commanders did not need a long C2 or C4ISR chain to inform combat. This meant that the ground forces of Gadaffi would not have moved far from the last positions Harriers noted before the new Harriers moved into attack positions.

This combination of compressed C4ISR and sortie rates created a deadly combination for enemy forces and underscored that using sea bases in a compressed strike package had clear advantages over land-based aircraft several hours from the fight dependent on C4ISR coming from hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

One more point about the ARG’s operations. The Osprey and the Harrier worked closely together to enhance combat capabilities. One aspect of this was the ability of the Osprey to bring parts and support elements to the Harriers. Instead of waiting for ships to bring parts, or for much slower legacy rotorcraft to fly them out, the 300-mph Osprey could bring parts from land bases to keep the ops temp up of the Harriers.

The highly visible pilot rescue mission certainly underscored how a vertically launched aircraft working with the Osprey off of the ARG can create new capabilities. The elapsed time of authorization to the recovery of the pilot and his return to the USS Kearsarge was 43 minutes. This rescue took place even though the US Air Force had a rescue helo aboard the USS Ponce. It was not used for two reasons. It would have gotten to the pilot much later than an Osprey team and the command and control would have been much slower than what the Marines could deliver.

The key to the Marines’ C2 was that the pilots of the Ospreys and Harriers planned the operation together in the ready room of the USS Kearsarge. They did not meet in virtual space. They exchanged information in real time and were in the same room. They could look at the briefing materials together. The Harriers were informed by fresh intelligence aboard the USS Kearsarge. The sea base brought together the assets and intelligence to execute the mission. The U.S. Marines used their land base largely to supply the sea-based air ops via Ospreys.

Second, having the C4ISR forward-deployed with the pilot as the key decision maker is crucial to mission success.

The USN-USMC team has a number of new capabilities being deployed or acquired which will enhance their ability to do such operations. The F-35B will give the Marines an integrated electronic warfare and C4ISR capability. The new LPDs have significant command and control capabilities. The new LCS could provide — along with the Osprey — significant combat insertion capability for ground forces and rapid withdrawal capability.

The ARG in Libya: The Osprey in Operation from SldInfo.com on Vimeo.

Honeycombing the Pacific: Crafting Scalable Forces

A new Pacific strategy can be built in significant part around the Cultural Revolution, which the new F-35 engenders in terms of inter-connecting capabilities through the C4ISR D enablement strategy.

No platform fights alone, and shaping a honeycomb approach where force structure is shaped appropriate to the local problem but can reach back to provide capabilities beyond a particular Area of Interest (AOI) within the honeycomb is key.[ii] The strategy is founded on having platform presence.

In World War II, especially in the Pacific theater, the concept of a “big blue blanket” evolved. It took thousands of ships and planes with appropriate logistical support to fight and win. Now with a 21st century electronic revolution of sensors, shooters and a honeycomb of networks, a modern version of a big blue blanket can be shaped which can enable the force.

By deploying assets such as USCG assets, for example, the NSC, or USN surface platforms, Aegis, LCS or other surface assets, by deploying sub-service assets and by having bases forward deployed, the U.S. has core assets, which if networked together – through an end the stovepipe strategy, significant gains in capability are possible.

Scalability is the crucial glue to make a honeycomb force possible, and that is why a USN, USMC, USAF common fleet as a crucial glue. And when “Aegis becomes my wingman” or when “the SSGN becomes the ARG fire support” through the F-35 C4ISR-D systems a combat and cultural revolution is both possible and necessary.

Basing becomes transformed as allied and U.S. capabilities become blended into a scalable presence and engagement capability. Presence is rooted in basing; scalability is inherently doable because of C4ISR enablement, deployed decision-making and honeycomb robustness.

The reach from Japan to South Korea to Singapore to Australia is about how allies are re-shaping their forces and working towards greater reach and capabilities.

For example, by shaping a defense strategy, which is not simply a modern variant Seitzkreig in South Korea and Japan, more mobile assets such as the F-35 allow states in the region to reach out, back and up to craft coalition capabilities. In the case of South Korea, instead of strengthening relatively static ground capabilities shaping a mobile engagement force allows for better South Korean defense as well as better regional capabilities to deal with the myriad of challenges likely to unfold in the decades ahead.

The introduction of F-35As into the USAF and ROK wings deployed to South Korea can set in motion innovations which can help the US and South Korean forces to re-design and improve defense capability within the Korean the Peninsula while setting in motion South Korean capabilities to play a greater role within the region. Korea could be an ideal area to shape a new CONOPS approach. North Korea has a large but linear force. By basing F-35As in South Korea, one is inserting a non-linear combat system. And the US can bring F-22s from Guam.

The U.S. would then have multiple vectors to confuse their military planning and disrupt any kind of linear attack they do. From a military technological point of view, this would allow the U.S. to get a big pause in North Korean thinking about whether this makes any sense or not to go to war. Inserting a chaos approach as opposed to just lining up the linear targets for the North Koreans would be a good thing. In turn inserting the F-35 As could actually foster innovation on the Army side on how to be more mobile, more distributed, and more agile.

Introducing the F-35As into South Korea will generate a whole new approach to linking C4ISR into a more effective deployable force.

As Secretary Wynne has underscored:

The gains are really if you have a distributed shooter set, it’s chaos to start with because the North Koreans have a very linear plan. In the artillery exchange, it was a very linear plan. In the points of crossings on the borders, it’s a very linear plan. The placement of their artillery pieces in the mountains depicts a very linear thinking on their part. And what they can’t stand and I don’t think they have the citizenry support to actually stand a non-linear solution set. So it will cause us to essentially rethink our whole game plan because it has to involve the surrounding terrain, the surrounding military where frankly we have to show the Chinese that we’re not planning on invading them and we will stop at the North Korean border. Korea is after all the last vestige of Yalta.

The recent decision by Japan to buy the F-35As is a significant move forward in shaping a new Pacific approach and capability. The Japanese understand the opportunity to leverage the F-35 combat systems enterprise and is a key reason why the Japanese down selected the aircraft.

The Japanese understand as well the significant opportunity which integrating Aegis with F-35 provides. The Japanese are a key Aegis partner and as such are in position to work on the integration of Aegis with F-35.

Combining Aegis with F-35 means joining their sensors for wide-area coverage. Because of a new generation of weapons on the F-35 and the ability to operate a broad wolfpack of air and sea capabilities, the Joint Strike Fighter can perform as the directing point for combat action.

With the Aegis and its new SM-3 missiles, the F-35 can leverage a sea-based missile to expand its area of strike. Together, the F-35 and Aegis significantly expand the defense of land and sea bases.

The commonality across the combat systems of the F-35’s three variants provides a notable advantage. Aegis is a pilot’s wingman, whether he or she is flying an F-35A, B, or C. Eighty percent of the F-35s in the Pacific are likely to be As, many of them coalition aircraft. Therefore, building an F-35 and Aegis global enterprise provides coverage and capability across the Pacific, which is essential for the defense of Japan.

And the commonality of the fleet allows hubs to be built in the region supporting common operations and shape convergent capabilities. The distributed character of allied forces in the region as well as the connectivity, which the F-35 allows as an interdependent flying combat system, diversifies capabilities against which a core adversary would have to cope with. Reducing concentration of forces and targets is a significant enhancer of deterrence.

Basing becomes transformed as allied and U.S. capabilities become blended into a scalable presence and engagement capability. Presence is rooted in basing; scalability is inherently doable because of C4ISR enablement, deployed decision-making and honeycomb robustness.

During President Obama’s visit to Darwin, Australia, the opportunity provided by commonality across the F-35 fleet was highlighted by the possibility of building a hub in Darwin for sustainment of an allied fleet as well as ISR sharing for common decision-making.

Darwin’s strategic location could become a hub of Pacific operations for Australia and a place to visit for its core allies. Singapore, South Korea, Japan, and the United States could all become key members of an Australian-based and Australian run F-35 hub.

Australia rightly wishes to preserve its independence. In being a partner in flying the F-35. The RAAF is joining a FLEET of aircraft –F-35 As, Bs, and Cs, which can be deployed to Australia for training, from bases in Singapore, South Korea, and Japan and off US ships and USAF air bases in the Pacific. The entire allied team can draw upon Australian air modernization to shape new capabilities for Australia, and diversify support for the F-35 multinational fleet.

The RAAF can go from being on their forward deployed airfield to becoming a hub for the F-35 fleet in several ways.

First, given the significant commonality among the three types of F-35s, a significant logistics and support hub can be based in the Northern Territories. The differences among naval air and air force air are significantly blurred by the commonality of the F-35s. This means that specific support for the As, Bs, and Cs could be generated. Based on the earnings from a logistics hub, the Aussies will be able to pay for a significant part of their own fleet modernization.

And a hub is not a permanent base. As an on-call service facility, the various allies can draw upon support when they are working with the Aussies on regional security missions.

Second, Australia has the large territory necessary for Asian F-35 fleets to train. The F-35 is not a replacement tactical aircraft; it is new flying combat system, which will need significant training territory for pilots to learn how to use all of its capabilities. As an aircraft, which has EW, built in, training to do cyber and EW ops are important. As a 5th generation aircraft, the ability to engage “aggressors” and to “defeat” air defense assets requires significant territory over which to operate as well. Instrumented training ranges over Australia and the contiguous ocean is invaluable for building the necessary skills to deter any aggressor.

As an added benefit, the Aussies will be major gainers of revenue from its various allies using the training facilities as well. With the logistics facilities and the training facilities, the F-35 could gain significant cash for the Aussie military modernization efforts.

Thirdly, the F-35 is a significant ISR asset. The Aussies can build ISR collection facilities, which can leverage the entire allied FLEET of F-35s operating in a regional security setting. They can use such facilities to shape an approach to link other allied ISR assets to establish a “honeycomb” network or grid along the Pacific Rim.

The reach from Japan to South Korea to Singapore to Australia is about how allies are re-shaping their forces and working towards greater reach and capabilities. For example, by shaping a defense strategy, which is not simply a modern variant Seitzkreig in South Korea and Japan, more mobile assets such as the F-35 allow states in the region to reach out, back and up to craft coalition capabilities.

If each element of the deployed honeycomb can reach out, up and back for weapons, which can be directed by the Z-axis of the F-35, a significant jump in capability, survivability, flexibility and lethality can be achieved. A scalable structure allows for an economy of force. Presence and engagement in various local cells of the honeycomb may well be able to deal with whatever the problem in that vector might be.

And remembering that in the era of Black Swans, one is not certain where the next “crisis” or “engagement” might be. But by being part of a honeycomb, the deployed force to whatever cell of the honeycomb, the force can be part of a greater whole, whether allied or U.S.

This means simply put, that the goal is NOT to deploy more than one needs to appropriate to the task. Vulnerability is reduced, risk management is enhanced and the logistics and sustainment cost of an operation significantly reduced. One does not have to deploy a CBG or multiple air wings, when an ARG is enough.

By leveraging the new platforms, which are C4ISR, enabled and linked by the F-35 across the USN, USMC, USAF and allied fleets a new Pacific strategy can be built. And this strategy meets the needs of this century, and the centrality of allied capabilities, not the last decade where the U.S. dealt largely with “asymmetric” adversaries with limited power projection tools.

The Way Ahead

By building on the F-35 and leveraging its capabilities, the U.S. and its allies can build the next phase of power projection within affordable limits. U.S. forces need to become more agile, flexible, and global in order to work with allies and partners to deal with evolving global realities.

Protecting access points, the global conveyer of goods and services, ensuring an ability to work with global partners in having access to commodities, shaping insertion forces which can pursue terrorist elements wherever necessary, and partnering support with global players all require a re-enforced maritime and air capability.

This means a priority for all Services in the re-configuring effort. Balanced force structure reduction makes no sense because the force structure was re-designed for land wars that the U.S. will not engage in the decade ahead. The US Army can be recast by the overall effort to shape new power projection capabilities and competencies in the decade ahead.

Retiring older USN, USMC, and USAF systems, which are logistical money hogs and high maintenance, can shape affordability. Core new systems can be leveraged to shape a pull rather than a push transition strategy. Fortunately, the country is already building these new systems and is in a position to shape an effective transition to a more affordable power projection capability.

At the heart of the approach is to move from the platform-centric focus where the cost of a new product is considered the debate point; rather the value of new systems and their ability to be conjoined is the focal point. No platform fights alone is the mantra; and core recognition of how the new platforms work with one another to shape collaborative con-ops and capabilities is central to a strategic re-design of U.S. forces.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Joint Forces Quarterly, July 2012.