2013-05-10 In an important policy statement, which seems to have moved rapidly off of the screen, Secretary of Defense Hagel re-enforced, in very specific ways, the U.S. support of Japan in the confrontation with China over disputed islands and in regard to the defense of Japan against North Korea.

There was some clear ambiguity left from Secretary of State’s visit to Asia, notably in appearing to wish to work more closely with China than Japan on the North Korean crisis. While in Japan, Kerry highlighted the importance of trade with China and the threat from climate change, and, also highlighted the threat from North Korea. What was not highlighted was what really to do about the North Korean threat, or any real recognition of the Chinese involvement in nuclear proliferation.

Each of the Pacific powers has a similar problem with China: they are the key trade partner, and a major threat. Managing the two AT THE SAME TIME is the challenge. What is missing is a clear deterrent strategy towards North Korea which includes a nuclear and a credible conventional de-capitation strategy against a regime which would understand little else.

A key problem is rooted in perceived differences among key allies in dealing with North Korea. For example, in this piece from The Japan Times there is a clear treatment of this theme.

The meetings Japanese leaders held this week with U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry in Tokyo revealed subtle differences in their approaches to North Korea’s provocations, with Washington leaning toward dialogue to defuse tensions and Tokyo toward staying firm.

The differences are even more apparent between Tokyo and Seoul, which has sought direct dialogue with Pyongyang.

“Our choice is to negotiate,” Kerry said Sunday after meeting with Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida. “Our choice is to move to the table and find a way for the region to have peace. And we would hope . . . that they would come to the table in a responsible way and negotiate that.”

But on Monday, after agreeing to work closely in responding to the provocations, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe told Kerry: “You mentioned dialogue, but we have been betrayed by North Korea before. I don’t want you to forget that,” a source with knowledge of their conversation said.

The former Massachusetts senator also praised South Korean President Park Geun Hye’s offer Friday to resume dialogue with the North, saying her offer “should be welcomed.”

Kerry’s attitude toward Pyongyang was “more conciliatory than we had imagined,” a government source said in Tokyo.

The article adds the following:

Meanwhile, Washington appears partially motivated by concerns that the situation on the Korean Peninsula could spin out of control over misunderstandings with the North. In a sign of its shift to a more conciliatory approach, the administration of U.S. President Barack Obama postponed the test launch of an intercontinental ballistic missile scheduled for April 9 to avoid the appearance of further provocations.

The United States is also seeking to strengthen cooperation with China, as the North’s longtime patron appears increasingly impatient with Pyongyang. Kerry praised Beijing for making what he said was a “strong statement of its commitment” to ridding the Korean Peninsula of nuclear weapons.

Amid signs that the U.S. and China may be getting closer, Japan is uncertain how effectively it will be able to push its views should the stalled multilateral talks on denuclearizing North Korea resume.

Even though Hagel in his press conference with the Japanese used many of the same words as Kerry, he had a refreshing concreteness about what these words meant. With regard to the islands, Hagel underscored that the disputes about sovereignty were important but that

Minister Onodera and I also discussed ongoing friction in the East China Sea, another key regional security challenge that must be resolved peacefully and cooperatively between the parties involved. In our discussion today, I reiterated the principles that govern longstanding U.S. policy on the Senkaku Islands. The United States does not take a position on the ultimate sovereignty of the islands, but we do recognize they are under the administration of Japan and fall under our security treaty obligations.

In other words, he was not leaving an Acheson moment on the table where the PRC leaders could assume that their bullying with regard to Japan was calling into question the role of US forces in the defense of Japan.

And throughout this crisis and in the Middle East, Hagel has demonstrated that his concern for allied security – which has been a hallmark of his years in public office and at the Atlantic Council – has been met with a very practical bent: what means can be generated to show practical support for Allies facing near term threats?

In the Middle East, it is the coming transfer of missiles to support Allied partners and with the Israelis, the sale of V-22s.

And in the Pacific crisis, he is the first Sec Def to move the Osprey onto the strategic chessboard.

As Hagel added at the Press Conference:

Earlier this month, the United States and Japan jointly announced a base consolidation plan on Okinawa. Its implementation, in concert with moving ahead on the Futenma Replacement Facility (FRF) will ensure that we maintain the right mix of capabilities on Okinawa, Guam and elsewhere in the region, as we reduce our footprint on Okinawa and strengthen this alliance for the future.

In addition, we confirmed the deployment of a second squadron of MV-22 Ospreys to Japan, which will take place this summer and increase our capabilities in the region.

Hagel is re-enforcing the importance of the Ospreys at a key time in the roll out of the capability by the USMC in the Pacific.

As 1st Marine Air Wing Commander, BG Owens underscored:

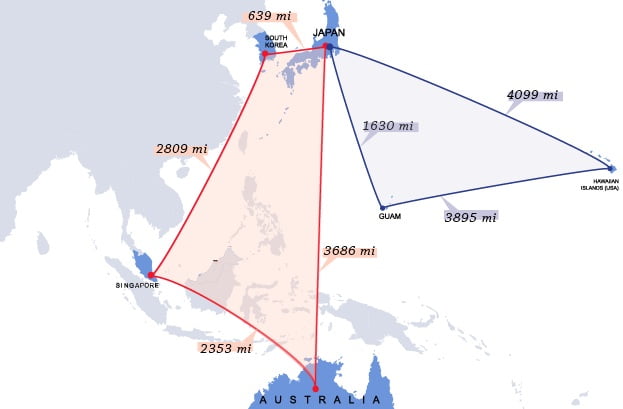

When you add to that the Osprey and its range and speed, you now have a wider selection of landing spots if we needed an intermediate support base.

A good case in point would be when we wish to deploy helicopters from Futenma to the Philippines, there are a couple of places that we must land for fuel. For one leg, there is only one site, which allows us to do this. But when you have an aircraft with greater range, it opens up more possibilities.

If, in a time of conflict, we were going someplace and an adversary wanted to deny us the ability to put in a refueling point or intermediate support base, they would have to now take into account a much greater number of islands. With only helicopters, an adversary could draw a 100-mile ring around a base and know where we could operate.

Ospreys, particularly when supported by KC-130Js, would significantly complicate an adversary’s attempts to predict our movements and operations.

And the Commanding Officer of the 31st MEU, Col. Merna, discussed the roll out of Ospreys to the MEU:

VMM 265 will be chopped to us later this month. We are going to ease into the deployment much as was done with the East Coast MEUs to ensure that we execute wisely with the Ospreys.

They will be part of our training with the Australians when we participate in Talisman Saber this summer. We will be training with them as well at Bradshaw Field, which is a training area, and part of the rotational involvement of the Marines with the Australians. The training will contribute to the Australian effort to get ready to use their own forthcoming amphibious capability as well.

We are intending to operate with a full compliment of 10 Ospreys during the exercise, with 3 self-deploying from Okinawa, and we are steaming away with the rest of them.

In other words, Hagel has underscored a real capability to assist in the dynamic defense of Japan, and not simply provided assurances without real content. This is a very important element of the deterrent approach in the Pacific. And in the years ahead, reinforcing the relationship with Japan is at the center of a build out of credible US and allied capabilities for deterrence and action in the 21st century.

Japan is a key technological partner for the United States throughout.

They are a founding member of the Aegis global enterprise. They are an investor and operational partner the SM-3 missile capability to enhance missile defense. They are a major player in the F-35 program, which will allow the shaping of an attack and defense enterprise. They are building a final assembly facility for the F-35 which will become a key element in the F-35 global procurement system, subject to Japanese government policy decisions. And they are keenly interested in seeing how the Osprey can shape greater reach and range for the “dynamic defense” of Japan.

http://breakingdefense.com/2013/01/15/partners-in-the-pacific-singapore-australia-and-japan/

In effect, since the end of the Cold War, Japan is evolving through two clear phases with regard to defense and security policy and is about to enter a third.

The first phase was extended homeland defense, where the focus was primarily on defending the homeland from direct threats to the homeland. A more classic understanding of defense was in play, whereby force had to be projected forward to threaten Japan and as this threat materialized, defenses need to be fortified. It was defense versus emergent direct threats to Japan.

Life changed. Technology made warfare more dynamic, and the nature of power projection has changed. The reach from tactical assets can have strategic consequences, the speed of operations has accelerated and operations highlighting the impact of “shock and awe” high speed operations made it clear that relatively static defenses were really not defenses at all.

At the same time, globalization accelerated, and with it the global significance of maritime and air routes and their security for the viability of the Japanese way of life. When terrorists crashed directly into the World Trade Center, Japanese got the point. No man was an island, and neither was an island economy simply protected by having a global policy of shopkeepers. More was required to defend the Japanese way of life.

The emergence of the Chinese colossus and the greater reach of the Korean crisis into a direct threat to Japan, and the resurgence of Russia, its nuclear weapons and its military forces, all posed the question of threats able to reach Japan rapidly and with significant effect.

A static defense made no sense; a “dynamic defense” became crucial. This meant greater reach of Japanese systems, better integration of those systems within the Japanese forces themselves, more investments in C2 and ISR, and a long-term strategy of re-working the U.S.-Japanese military relationship to have much greater reach and presence.

In other words, Hagel seems to get this and has acted on the assumption of the centrality of the US-Japanese relationship in shaping 21st century deterrence and has acted on that basis to enhance some of the material means to do so.

And it seems the PRC is working hard to bring together the two greatest maritime powers of the 20th century.

Our forthcoming book to be published by Praeger Publishers provides an extended look at the evolving US-Japanese relationship within a 21st century strategic context.

Robbin Laird, Ed Timperlake, and Richard Weitz, Rebuilding the US Military: Shaping a 21st Century Strategy.

An earlier version of this piece appeared on Breaking Defense