2014-07-10 An Interview with Air Vice -Marshal John Blackburn AO (Retd).

In an interview with Murielle Delaporte in May 2014, Air Vice-Marshal John Blackburn assesses the evolution of military logistics in Australia, which unique geographic circumstances are a challenge all in itself.

Expeditionary by nature, the Australian Defence Force has been careful to limit its vulnerabilities by taking specific decisions, such as investing in strategic capabilities and diversifying its supply chain.

However, there is now a change in the game with the increased globalization of the latter both commercially and militarily.

The change of technology brought in, in the case of Australia, with the acquisition of the Joint Strike Fighter, means a switch in business model and therefore in logistics concept of operations.

As AVM Blackburn stresses, « in terms of military planning, we have been relying on contingency planning for operations essentially based on individual military platforms, as opposed to assess the right military capabilities for the desired military effect.

The key message is anticipation… ».

And logistics is a big part of that anticipation’s puzzle the former Deputy Chief of the Royal Air Force is concerned about.

The ongoing changing nature of logistics also means, for AVM Blackburn, a change of culture so that logisticians keep « making things work » the way they always manage to, but with less systemic risks involved…

Expeditionary by Necessity

Australia has a unique geography, i.e. a vast territory with a small and very distributed population and infrastructure base, which means that any military training or manoeuver we do in the country requires long legs and is by nature expeditionary.

We have to take our supplies with us in order to maintain our thin line of supply.

The support of operations in the Northern part of Australia, where population and infrastructure are scarce, mostly originates from the South Eastern part of the country.

So we do have an operating model that prepares us for deployment. Australia’s unique geography and circumstances have indeed prepared us to some extent to expeditionary projection force.

In addition, in the past decade, we have had a lot of experience of deployment overseas, particularly in the Middle East. We used our own logistic system, but also plugged into those of our Allies, particularly the American system.

It is quite different than when we try to be self-supporting, like we did in East Timor. In Afghanistan, we are part of a bigger force and it is a very different model.

Although we do need substantive lines of supply through the Middle East, it was easier to send forces over there than to bring back the repairables to Australia.

In the wake of Iraq and Afghanistan, we acquired strategic lift vectors – we have six C17As now – and we are acquiring a regionally significant amphibious ship capability. We have some autonomy and the ability to deploy rapidly thanks to a pretty reasonable lift mix for a small force: we have C130Js, KC30 tankers, soon the MRTT once the boom will be certified, and we are acquiring C27s for tactical lift.

But the ability to sustain our deployment is where the supply chain comes into factor and is what we are concerned about.

Stockholding and maintaining a diversity of supply have been one way to cope with geographic isolation, but we learned some key lessons:

Our stockholding policy needs to be performance-based as opposed to “Best-Endeavor-based”

Preparedness, based on certain levels of readiness and sustainability levels, is what drives our stockholdings.

However, budget constraints mean that you sometimes compromise these levels of stockholdings, and therefore end up relying more on the supply chain to respond.

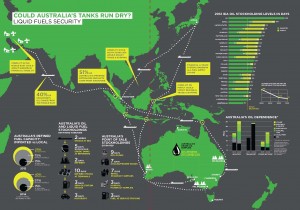

We are in a similar situation regarding our energy supply. For example, Australia’s combined dependency on crude and fuel imports for transport and defense purposes has grown from around 60% in 2000 to over 90% today.

While our ‘just in time’ oil and liquid fuel supply chains work well under normal circumstances or during small scale or short duration interruptions, the resilience of the supply chains and associated infrastructure under a wider range of plausible scenarios has not been assessed.

Indeed, there are no fuel stockholdings in government and our Government does not mandate stockholdings in the industry (in contrast to EU countries), which means that our civilian infrastructure is not in a position to support the military.

Fuel contracts to support the Northern part of the country is “best endeavors only”, which means that there is no penalty for failing to deliver.

We have in addition very little resilience, as imports are only shipped through a supply infrastructure that has single points of failure.

It has become worse in the last decade because we are almost fully dependent on oil refineries in Asia and, as logisticians are already busy with their own supply chain issues, sustainability and supply are assumed.

We already had a warning, while operating in East Timor, where we were left with only a few days of fuel in the country during that operation[1].

We cannot of course be fully autonomous given the reality of our supply chains. We operate on a scenario-based viability period, and our readiness defines our sustainability levels and our stockholding. But the challenge lies in the fact that if you can set a level and measure whether you can maintain it at any point in time, how do you predict your future preparedness levels

Supply’s diversity must go hand to hand with interoperability requirements

We have made a conscious decision to maintain diversity in our supply base, which comes from the United States, the United Kingdom – given our traditional ties – and increasingly from Continental Europe, with for instance the acquisition of the Airbus Helicopter’s (former Eurocopter’s) Tiger attack helicopter and the MRH90 Troop Transport Helicopters and Alenia’s C27.

Europe as a whole accounts for about 37% of our aircraft platform types, while the USA represents roughly the remaining 63%.

One of the lessons we learned from such a diversification is that when purchasing foreign military equipment, we have to specify interoperability standards from the outset.

We need to ensure we have the right data links and that we achieve interoperability across the force, as we are too small of a force to have the American and European sourced platforms working separately from each other.

We are encountering data-link issues with the Tiger in particular which, because it is linked to a proprietary ground station link, cannot be directly interoperable with our other air platforms.

Our domestic organization has improved in terms of warehousing.

However, a lot of commercial activity is « just in time », which is fine commercially, but in a defense organization, you need to have a bit of « just in case »…

If you outsource without a good contracting mechanism, it can end up in « just in time » only.

In the 90’s, we did a lot of externalization, as the Australian armed forces were being downsized. As the RAAF went from 23 000 down to 12 500, we outsourced so much that we lost our engineering and logistics capabilities.

It took us ten years – and a few incidents along the way because of a lack of depth of supervision – to recover it.

The same goes in our military health capability, which is largely civilianized today, depriving us from an adequate surge capability in the case of high demand military operations.

At the end of the day, short term commercial rationalization without understanding the systemic risks at stake amounts to short-term thinking; we unfortunately have been guilty of that in some cases.

The Changing Nature of Logistics

The traditional challenges we met in the past in the supply chain are nothing truly unique, although our geographic position does not help, since you need very long supply chains in the South Pacific.

But, even though imperfect, we had in the past a logistics system allowing us to support ourselves to a greater degree. We ran into the same issues as everybody else: we have for instance always been concerned about ammunition supply or our weapons production capability, since, no matter how large the amount you manage to carry with you, everybody wants them at the same time once in operation.

The challenge we are now up against, though, is facing the logistics system changes associated with the coming of the next generation equipment.

There are two major issues at stake which we need to address:

What are the implications of a changing model for logistics support as exemplified by the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) and its global supply chain approach? The commonality of spares across the supply chain means that you do not necessarily own all the parts yourself.

It is a neat economic concept, but because it is not built yet, there is no evidence of how it is going to work in a contingency.

How do you build an information system to support the new logistics support model and interface with an old style of supply chain management?

Integration does not seem realistic, but interoperability is the key word in this case.

The builder builds a platform/product, but it is not their responsibility to make the overall defense system work.

The maintenance aspects of the contract are competed. What is changing right now is the construct of owning your spares and defining a contract and support service in-country, while you are part of a global supply chain.

In the case of the JSF, Lockheed Martin is in charge of a global supply chain based on shared spares. The fighter is part of a much bigger supply chain managed by a system called ALIS (autonomous logistics information system).

The system is managed as a global entity, not as an « Australian stovepipe ». So what you are talking about is a change in the concept of support logistics, as a result of the change in technology.

How do you interface with a legacy logistics system such as that in Australia is still unclear.

Will we have to manage each of these lines as separate supply chains with their own information system?

How do we aggregate that to make it work is the second question…

So we have to do some systems analysis and risk assessment in terms of our defense preparedness.

Until recently, you used to have much more control; it was a slow and imperfect system, but you had control over it and you knew what you had; stocks were yours and you could measure the pace of replenishment.

The IT systems were designed for that and fit the Australian needs.

We cannot turn back to the old ways of doing business, so we have to be interoperable.

There are advantages, and we could probably not afford the JSF otherwise, so the question is how do you plug into legacy systems, which were never designed to operate that way at all and what is the impact on our preparedness and supply chain’s availability assessment. We have to think of it as a “Fifth Generation” logistics system trying to operate with a Third generation logistics infrastructure!

The JSF is not only a Fifth Generation platform, it is also a Fifth Generation logistics system. Managing the supply chain is paradoxically at risk of becoming more complex and more compartmentalized by fleet than in the past.

We also depend more on the manufacturers, while having, in the case of Australia, little control over the security of our shipping lines, which has become totally commercial.

Without a national shipping line or a national airline, we are totally at the mercy of commercial transportation.

So the way to understand maritime security is twofold: one is the threat and the other one is the existence of potential choke points, such as the Malacca Strait. The impact of regional conflicts on the supply chain needs to be analyzed and we need to improve our overall understanding of how the supply chain functions. Our attitude tends to be to trust the market to adjust and fix everything.

The resilience of these supply chains needs to be assessed, as distances and potential disruptions are a big issue, while the possibility of an unfriendly neighbor in the future is not to be disregarded.

« Making it work »

What we have been trying to look at in the Kokoda Foundation’s defence Logistics study that I undertook with my coauthor Dr. Gary Waters, is what are the underlying reasons behind the logistics system problems and do we have a risk-avoidance strategy for the future?

Is there anything we can do about it? Our conclusion is somewhat simplistic: the logisticians have always been doing a very good job at making things work, in spite of the limitations of the existing logistics system: professional pride, professional skills.

The culture of any logistician I have ever come across is « to make it work somehow ».

But in doing so, with this « can do » attitude, they sometimes manage to disguise or repress the weaknesses in the system or the systemic design issues.

As a consequence, outside of the logisticians, very few people understand the essentiality of the predictability of the function, or where the vulnerabilities or risks are.

Understanding risk and capability limitations is not always appreciated. In the last five years, we had a very difficult situation where our Defence Forces were unable to deploy our key naval capabilities in support of an operation.

Because of multiple problems, barely two out of a fleet of six platforms were operational-ready.

Instead of the blaming game that followed, identifying the common problems is what will bring change. As mentioned earlier, in the 90’s, we almost reduced our forces in half. That was a significant down-sizing of the Defence Force and the people in charge of that process focused on the operational capability, the platforms. In the RAAF, we cut into and outsourced a lot of our logistics and engineering skillsets that went to the industry.

As a result we nearly killed the logistics and engineering categories in the Air Force.

The subsequent result was a significant increase in risk in terms of airworthiness and safety.

This occurred under an archaic concept called the “teeth to tail ratio”, where we devalued the importance and essential of the supporting or enabling functions in our Defence Force.

Another problem in Australia is related to culture and control: the services Chiefs in our case are responsible for capabilities and can make decisions over platforms. When you look at the support side, there is no lead capability manager for that function, even though it is a critical enabler. The logistics Chief is a two-star joint coordinator, but he does not have the same authority as the single service chiefs. As a result, the logistics leadership is viewed as being fragmented.

Capabilities have been acquired, without checking what is vital in terms of the logistics necessary to support it as an end to end system. Since we do not give logistics the same level of priority as a ship or an airplane, it gets managed in an ad hoc way with a large overhead induced by having to coordinate across a large organization without the authority. When you do that, the results are predictable: you do not have a concept of operations based on a business architecture based on logistics, you do not get priority in the authorization system, so things get delayed, because there was no leading voice to say « this is critical ».

There is an example of a critical joint project called JP2077 Phase 2D, which was supposed to be the logistics IT integrator able to integrate the stovepipes in the logistic systems. This project has been delayed year after year, because its critical impact is not widely understood. Because of a fragmented system, we are about to introduce our new amphibious capabilities and the new JSF fleet, without an integrated logistics information system.

Our logistics support for operations is good, but we lack the ability to rethink, redesign and anticipate the significant changes in logistics we will face in the next decade. The new approach brought in with the JSF acquisition raises fundamental questions: how to integrate profound changes in business models as a result of changing technologies, as well as how to adapt defense and increase interoperability. It is not solely a change in a technical interface, it is a shift of business model.

Anticipation is key, as well as an increased cooperation among allies in order to find common standards and approaches aimed at reducing our supply chain vulnerabilities.

The globalization of the supply chains implies that we are all likely to experience the same problems.

[1] The International Force for East Timor (INTERFET) was commanded by Major General Peter Cosgrove and led by Australia in accordance with United Nations resolutions to address the humanitarian and security crisis which took place in East Timor in 1999 and 2000. Australia continued to support the UN peacekeeping operation with between 1500 and 2000 personnel, landing craft and Black Hawks and remained the largest contributor of personnel to the peacekeeping mission till the end of the mission in 2012.

Editor’s Note: This article was first published in the Summer 2014 issue of SOUTIEN, LOGISTIQUE DEFENSE SECURITE