2015-04-28 By Robbin Laird

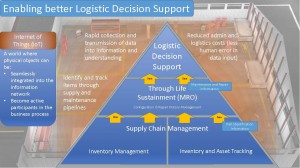

Leveraging commercial technologies for defense purposes and learning from applications of commercial systems to defense needs provides an important learning cycle for cost reduction and enhanced effectiveness for logistics management systems.

The GlobeRanger software systems and decision-making tools are positioned for the sweet spot to provide such an outcome.

A case in point is how the company is evolving a comprehensive approach to hangar management leveraging its various tool sets to deliver logistical management to deliver more effective decision-making.

The approach is being shaped in a partnership with leading businesses in the commercial aviation sector, and this partnership then provides an operational base from which such an approach can be applied to the defense sector, such as management to the new F-35 hangars being built to support the global enterprise.

To understand how hangar management can be reshaped using the GlobeRanger tool sets and decision-making approaches, I interviewed Phil Coop during my visit to GlobeRanger in Richardson, Texas earlier this year.

Coop spent 17 years with American airlines as a maintenance technician and then became a maintenance manager and then moved to Boeing.

At Boeing, he was part of shaping the GoldCare support program for the 787 DreamLiner.

With a new 21st century aircraft came a rethinking of the system to support that aircraft and to provide life-cycle support to the fleet as well.

According to Coop:

During the 787-support program development and the development of the maintenance service we discovered RFID technology for use on the aircraft.

And we really developed some unique ways by partnering with airlines with how to use RFID. And RFID quickly became my full-time job for Boeing.

Through the years of working with the airlines, Japan Airlines, American Airlines, etc. we developed a concept for an RFID-enabled aftermarket solution.

And in the ten years that I worked on that project with Boeing and in the ten years that we worked ways to leverage RFID with the airline industry, we I developed a close working relationship with Fujitsu who was at that time my business partner.

So when the commercial aftermarket RFID program was cancelled at Boeing, it made sense for me to join Fujitsu and continue my work on RFID-enabled support to commercial airliners.

Coop is an example of Fujitsu leveraging GlobeRanger technology and vice versa, for now Coop can work a lower cost RFID-enabled solution sets for more effective sustainment solutions for the commercial airline industry.

But rather than pursue case by case airline contracts, Globe Ranger is partnered with other leaders in the industry in shaping a comprehensive support solution set.

According to Coop, “the GlobeRanger solution brings with it a mature technological approach and a very good price point for the industry.”

“Additionally, we are taking bite-sized solutions and building from them into a comprehensive solution set.”

Coop provided several examples of how sensor-enabled maintenance can improve the process, in terms of both accuracy and the speed of performance.

And by using sensor-enabled information, the maintainers can provide a more effective and cost effective approach to maintenance and sustainment.

One example was with regard to life vests.

Coop explained:

When we take a plane, we all have heard the safety announcement about the life vests below the seats without ever expecting to use them.

But for the airlines and the regulators these life vests need to be inspected, maintained and replaced on a regular basis.

In the legacy way, technicians look under every seat on a periodic cycle to verify the serviceability of the life vests, and the airlines need to keep a stockpile of life vests to replace those which need to be replaced.

The stockpiles are costly, and the examination time consuming.

In the GlobeRanger approach the life vests have sensors to indicate their condition status and by coming onboard the technician can readily determine where he needs to go within the plane to deal with a life vest which needs attention.

This information can be sent to the company’s Enterprise Resource Planning systems to provide information with regard to just in time delivery of supplies, rather than having to stockpile life vests.

And by breaking down the work process of maintenance, the key building blocks of generating information targeted for comprehensive maintenance solutions can be built and by cross linking those information flows a more comprehensive approach to hangar management is possible.

That is the approach of GlobeRanger in building out their new comprehensive solution set based on accurate and timely information generated from the edge of the operation.

And because it is about empowering technicians and maintainers, they have a key stake in the accuracy and effectiveness of the information as well.

It also helps regulators as well to have more effective information as well to ensure accuracy in the process, but without having to do procedural intervention in favor of informed intervention.

The hangar piece of this is a big deal for the maintenance process.

As Coop describes it, when a plane comes in for its major maintenance milestones, the plane is pulled apart and the parts are distributed throughout the hangar, back shops and external vendors, examined, repaired and then sent back to the bay where the plane will be put together again for its next operational cycle.

When an airplane comes in for heavy maintenance and there are two or three days of offload.

The airplane literally is gutted. Engines are removed, flight controls are removed, the entire airplane cabin, the interior is removed until it’s nothing but a structural shell.

The avionics equipment is removed, landing gear, and major components come off the airplane.”

The parts are handled manually, and can be lost and have only paper information about their life cycle.

The moment the parts leave the airplane visibility typically today is lost.

Today, we typically have a maintenance planner or scheduler who for lack of better terms is a conductor trying to orchestrate the offload of systems and parts from the plane and then reload onto the airplane with really limited tools to manage the process.

They’re relying on feedback from the shops who receive the components and say, “Yes, I got it at this time. I expect to be finished with it at this time.”

By building in sensors into the parts, there is asset visibility.

One can have encoded information about their history, their performance, and can be rapidly located throughout the hangar.

Even more importantly, when the plane is put back together again, the hangar manager can schedule which work crews should be on the plane at what time and in what sequence.

The current situation is structured anarchy.

In many ways every airplane is a discovery when it shouldn’t be.

There’s usually several groups of technicians involved in the process of dissembling and assembling a commercial aircraft.

There’s the avionics team that does all of the electrical and navigation communication. They’re responsible for all of the electronic systems. Their job is to remove and then reinstall all of that equipment and functionally test it to make sure everything is performing correctly.

Then there is the propulsion group, the guy’s that work on the engines and the associated systems. Typically, they’re responsible for the fuel cells as well. So they’ve got wing tanks all opened up, they’ve got engines either opened or removed. They have a lot of components out of the airplane as well.

And then there’s the cabin and the structures guys who basically remove all the interior structural pieces and then fix them and then reinstall them.

All of these groups are competing to operate on the same real estate.

A really good example of that is the flight deck.

If we don’t have things sequenced correctly we can have an avionics technician installing navigation equipment and needing to do an operational test on that equipment at the same time that we have the propulsion team installing a component and needing to functionally check that system.

And somebody from the flight control team is doing the same thing.

So everybody is competing for this little piece of real estate on the airplane.

And it becomes a feast and famine process.

There’s really no good way to manage it with the current process.

The conductor or the maintenance planner or the scheduler doesn’t have a lot of great visibility into the process in real time and they don’t have any tools to rely on to say to the avionics technician, okay, it’s your turn., the flight deck is ready for you, we’ve finished other tasks, move in.

In other words, by providing sensor-enabled information, a new work flow can be established based on the true start of affairs rather than simply building one around historical procedures and projections.

In effect, what one can do is shape a 21st century approach to hanger work flows, which for the military will have a clear impact on aircraft availability rates, and in a time of airplane scarcity, it is not hard to see why a new approach is essential.

It is easy to see why an MRO provider would clearly wish to see such a hangar management approach be shaped and implemented, for efficiency, effectiveness and cost savings are all improved. And safety enhanced and made more transparent for regulators as well.

And there is a generational change aspect to such a shift as well.

As Coop put it:

When I was a mechanic getting a cool new Snap-On wrench was as sexy as it got and I loved that.

The kids today they need gadgets, they need applications, they need to network.

And as we transform the maintenance environment from a kind of the prehistoric manner that it’s in today where we’re still maintaining airplanes the same way we have for 30 years we need to catch up with the new generation.

When we start bringing these gadgets into the workplace, the tablets, the RFID readers, the network technology, we are playing to the strengths of the new generation of maintainers.

It is clear why a new aircraft program like the F-35 would like to build such capabilities in from the outset and to deliver capabilities appropriate to the I-pad generation maintainers.

And the commercial side of the house is clearly demonstrating that this is doable as well as cost effective.

This is not about acquisition reform; this is about adopting commercial best practices.