2015-12-07 By Robbin Laird and Ed Timperlake

The decade ahead is not a repeat of the past 15 years; it is not about a continuation of the land-centric and counter-insurgency slow motion war.

It is about global agility, the ability to insert force to achieve discrete and defined objectives, and to maneuver in the extended battlespace to work with allies and joint forces to credibly prevail in the range of military conflict across the range of military operational situations.

For the power projection forces –USN/ USMC, USAF with appropriate elements of the US Army, especially Air Defense Artillery – it is about the capability to work across an extended battlespace with flexible means which can be linked together as necessary to prevail in the military and strategic conditions facing the US and its allies in the period ahead.

It is about building capabilities at the high end, which have the flexibility to operate through the range of military operations or ROMO.

It is about powerful and flexible force packages which can operate and dominate in specific military situations but be linked to other capabilities to provide the kind of reachback and dominance which effective deterrence requires.

In our book on the Rebuilding American Military Power in the Pacific: A 21st Century Strategy, we highlighted several key elements required to shape 21st century war winning deterrent forces.

By leveraging some of the new platforms coming online and replacing older, costly, and stove-piped platforms and systems, a new scalable force structure can be built. And at the heart of doing so will be the inclusion of allies and U.S. forces within a modular scalable structure.

The strategy is founded on having platform presence. By deploying assets such as USCG assets— for example, the national Security Cutter, USN surface platforms, Aegis, or other surface assets— by deploying subsurface assets, and by having bases forward deployed, the United States has core assets that if networked together can end a stovepiped acquisition strategy of platforms bought separately from one another and make significant gains in capability possible. Scalability is the crucial glue to make a honeycomb force possible…..

Two other key elements are basing and weaponization. Basing becomes transformed as allied and U.S. capabilities become blended into a scalable presence and engagement capability. Presence is rooted in basing; scalability is inherently doable because of C5ISR enablement, deployed decision-making, and honeycomb robustness.

The reach from Japan to South Korea to Singapore to Australia is about how allies are reshaping their forces and working toward greater reach and capabilities. For example, by shaping a defense strategy that is not simply a modern variant of Sitzkreig in South Korea and Japan, more mobile assets allow states in the region to reach out, back, and up to craft coalition capabilities.

The approach we have suggested is built around “no platform fights alone,” whereby we look at key platforms as nodes in a honeycomb force, which can act with effective lethality throughout an extended battlespace.

Those platforms which can operate in an interconnected manner are the crucial ones to build, deploy and sustain in the period ahead, versus those which are very limited in their capability to provide synergy to joint or coalition forces in the battlespace.

This means as well that force packages need to be examined, less in terms of themselves individually, but rather in terms of their synergy and capabilities to shape dominant combat power in the interconnected battlespace.

To discuss the way ahead for the sea services from the standpoint of the head of Naval Warfare, we had a chance to discuss key elements of innovation being put in place.

Rear Admiral Manazir, the Director of Air Warfare on the Staff of the Chief of Naval Operations, sat down with us in November 2015, to discuss the way ahead.

Question: As global events unfold, most dramatically the reach from the Middle East to Paris and back again, how do the sea services contribute to the fight?

Rear Admiral Manazir: The Navy/Marine team has always been expeditionary; it was at its inception 240 years ago for both services.

We have always been expeditionary.

We design the Navy / Marine Corps expeditionary force to be able to engage against a nation state when necessary.

That could be all the way from what people technically refer to as the high-end anti-access area denial fight all the way to putting power ashore to engage in counterterrorism fights.

The Marine Corps has grown in capability from being naval infantry to now having the capability to come from the sea with high-end meshed, networked, honeycombed, resilient capability, with an array of options depending on how you integrate the force.

The sea base itself has a powerful ability strategically to wage war because you don’t need a permission slip from a foreign power to use their bases.

The United Stated Navy and the United States Marine Corps singly in the world have retained and modernized the sized capability that allows one to fight a nation with our force rather than just fight another naval force.

Question: Put in other terms, a force capable of being sized to the mission?

Rear Admiral Manazir: That is right. Our modernization strategy will make us even more effective to deal with the future mission set.

What the higher-end capabilities that are delivered with F-35B and C and then the future air wing that includes unmanned give us is the capability to really own that battle space, and all domains of it. It can be flexed from the higher-end war fight down to delivering combat power ashore from the sea base.

Going into a high-end battle space with F-35Bs and Cs will allow us to identify more of the players in that battle space than we did before. With the information gathering and data fusion capability resident in the F-35, you can empower the rest of the air wing.

The F-35 is truly revolutionary technology.

The ability to bring in that much information into a single platform, share it together via machine language and put that picture together is game changing. The ability to then coalesce that much data into knowledge is unprecedented.

If you are operating over the battle space, like a counterterrorism situation, where you have a lower-end air-to-air threat, you can operate, and persist over a ground battle space as you collect information and shape a much more rapid strike capability as well. The decision cycle can accelerate in either the higher end or lower end fights.

The point can be put simply: we are expanding our capability to shape an agile force to operate throughout the battlespace and to deal with the spectrum of threats which a sea base would be tasked to operate against.

The F-35 will be a contributor to shaping the overall modernization strategy.

The F-35 has a powerful ability to share information, the ability to sense the battlespace, whether it’s signals from a surface naval vessel, signals from an air contact, ID-ing the air contact at long-range, or processing and identifying targets on the ground, all tasks that we’re going to have to do going forward to win.

Question: When we were at Fallon, the air wing training to go out on deployment was in real time communications with the Bush on deployment in the Middle East.

And the Fallon team is working hard to evolve the approach to Live Virtual Constructive Training in order to be able to fight effectively in the expanded battlespace with higher speed warfare and operational dynamics.

How do you view the impact of these new capabilities on shaping the sea base going forward?

Rear Admiral Manazir: The ability to share information between decision-makers and staffs that are not all geographically located, is getting better and better. This allows not only dynamic combat learning but provides greater fidelity to the training process as air wings prepare to deploy.

In the past, we only sent text reports. Now we are sending full motion video. The EA-18G Growler can send actual data back to the warfighting center and say: “We have not seen this signal before, what is it?”

And then the labs can run it through their data libraries and work the problem to ID the signal and send their findings back to the deployed fleet.

The F-35s coming to the fleet will add significantly to this process. It is about rapid combat learning in a dynamic warfighting environment.

We are shaping the foundation for “learning airplanes” to engage the enemy.

LVC will enable us to train in a more robust environment than we are on our current ranges that are geographically constrained, and currently do not have the full high end threat replicated. LVC will allow us to train to the full capabilities of our platforms across a variety of security environments and do so without exposing our training process to an interested adversary.

Question: What you are talking about is shaping real time combat forensics against an active and dynamic threat?

Rear Admiral Manazir: That is a great way to put it. And this capability is crucial going forward.

We’re back into a scenario where lots of threats around the world require us to react to enemy learning. Then, when they act in accordance to our reaction, we react again and so on. The enemy morphs to do X. We have to react and we now do Y.

What is not widely realized is that the evolving air wing on the carrier and on the large deck amphibious ships, is being shaped for a dynamic learning process. The F-35s will play a key role in this evolving process, but we are already underway with this process as you mentioned with regard to Fallon.

With regard to the air war, where it’s either air-to-ground missions or air-to-air missions, we can share that information and bring in more people into the discussion with our long-range information and communication systems.

That kind of capability is foundational to the evolving air wing.

We’re also working on the capability to bring in national technical means into a cockpit where the synapses that are required to do that are significant to be able to have something with a relatively low latency.

Imagine an off-board sensor that gives you a piece of information in the battle space that you can get into the cockpit and adds to the information you already have. It’s about closing down the information deltas that we have traditionally considered as a strategic national asset with a tactical naval asset.

And we’re closing down the connection lines between where we get that information and conveying to the warfighter.

There is a constant effort to enhance the ability to get intel to the warfighter so he can act on it.

Question: What you are describing is the fighter wing as sortieing of information, and not only weapons?

Rear Admiral Manazir: That is a good way to put it.

We are doing what Bayesian theory talks about, namely we are providing more and more information to get closer to the truth in targeting or combat situation. One can reduce that fog of war by increased understanding of what actual truth is, you’re going to have better effects.

This is why the technology that the F-35 brings to the fight is so crucial.

You have decision-makers in the cockpit managing all of this information.

With Block 3F software in the airplane, we will have data fusion where you transform data information to knowledge enabling greater wisdom about the combat situation.

The processing machines in the F-35 provide enough of the fusion so that the pilot can now add his piece to the effort.

This enables the ships to enhance their ability to operate in the networks and to engage with the air fleet in dynamic targeting at much greater distance.

It is about reach not range for the honeycomb enabled expeditionary strike group. The F-35 is a key enabler of this shift, but it is part of an overall effort to operate in the expanded battlespace.

Question: Visits to the USS America, to CVN-78 and to the Queen Elizabeth, all highlighted the importance of building ships which can provide what one might call 21st century infrastructure of combat air.

How do you look at the Ford, for example, through this lens?

Rear Admiral Manazir: It is a 21st century naval infrastructure asset, which lives off and further enables the transformation of the air wing.

It’s a facilitator for all the things you’re going to do off the flight deck.

The electrical generation capacity on the Ford is three times what the Nimitz’s is.

It gives you the ability to put greater electronic systems on to the ship.

The ability to have high power requirements with high cooling requirements for your data servers is enabled by the ship.

It has the capacity to be able to support those things and in conjunction with the high-end air wing we’re building, you’re going to be able to do the missions we discussed earlier more effectively in the expanded battlespace.

The Ford’s infrastructure will be partnered with the airplanes that come on and off the flight deck.

Question: What you are describing is a shift from thinking about the carrier as the deck which can fly X number of aircraft to thinking of the carrier as a moving epicenter of an extended strike enterprise, that can work with the USAF and coalition partners and live off of their combat capabilities in the expanded battlespace.

Is that what you are arguing?

Rear Admiral Manazir: Absolutely.

The focus is upon the carrier as a moving epicenter for a netted capability with the joint and coalition force.

It is not about counting the number of airplanes on the deck or projecting the future existence of paper airplanes.

It is about the air wing we are building and how it will operate with the transformed joint and coalition forces we are collectively modernizing.

The approach is to have force structure flexibility with an interconnected extended battlespace.

You can operate as a separate force package; or as a federated force when you are connected but can plug and unplug; you can be interoperable, integrated or interdependent; depending on time, circumstances and mission.

What the Ford class, the Joint Strike Fighter and future unmanned platforms bring is the ability to pull the information in and be an epicenter of an enlarged and extended reach for the joint and coalition force.

Question: The expeditionary strike group as a sea base is seeing significant increase in its flexibility with the changes in the amphibious as well as carrier fleet. It really is an engagement force, which can allow for significant operational flexibility.

How would you describe the evolution of the sea services with regard to the way ahead?

Rear Admiral Manazir: You can describe it in terms of continuity of change and transformation.

They are engagement forces; they are presence forces; they are deterrent forces. They are extensions of the National Command Authority.

In the old days, way back when Perry opened up Japan, he was an independent Captain given mission orders and off he went.

In World War II, they were given mission orders and off they went.

Through the 60s, naval forces operated to deter. The Strike Group commander had communications back to the National Command Authority. The links were limited and text based.

Now, you have the real ability to actually have a fundamentally robust connection with the engagement forces forward at sea and one can pursue Bayesian logic, getting down towards more truth in the picture. You start to reduce the fog of war that comes from misinformation, or a different understanding of the battle space.

And as you reduce the fog of war by increased understanding of what actual truth is, you’re going to create better effects from the use of force.

The great thing about naval forces is that we can move in and out of operational sanctuaries, and the Navy Marine Corps team can move to the area of interest and the point of attack. You can take that capability, whether it’s in the Eastern Med or in the Western Pacific, with the reach of this network-enabled combat force, and especially when you start to link it together with coalition partners, you start to grow a honeycomb mesh of integrated networks that are all sharing information.

And the reach of this combat capability is greater than what flies or is launched off of any particular combat ship.

Question: They are some critics who focus on the Navy building too complex of platforms for new sailors to operate. Our observations are somewhat different from either operating on or visiting Naval platforms – complexity is there but the focus is upon the ability of sailors to operate more automated systems as well.

How do view this challenge?

Rear Admiral Manazir: I’d push back against anybody that says we make our systems overly technical for our sailors to operate. Our most important war-fighting asset is the United States Navy sailor.

The sailors that are on Ford, we’re training them at the level that the technology is advancing. Our air crews that are in our F-35s are trained to operate that weapon system. They are expert at that higher technology weapon system. We train them to be part of that weapon system.

We put a program together that doesn’t just give them a piece of equipment and say here, go figure this out. We are the best in the world at building training systems that optimizes our technology.

What we really get, though, through the inventiveness and the ingenuity of our sailors and junior officers is that they take their weapon system, which is now more software-driven than it is hardware, and drive it’s capabilities forward, enhancing the warfighting impact of the new technology.

And based on growing up in a data-rich word and growing up in a machine-rich world, they know how to take this weapons system to a higher level than we even designed it for.

For example, the recommendations we got coming back from the first deployment of the Growler, was that they’re developing tactics for us that we did not envision when we first sent it out on the ship.

The new systems rely on significant machine to machine and man to machine interfaces. We are finding that the best way to enhance the machine-to-machine learning is to make it a man-machine interface to enhance the dynamics of change in the machines and the quality of combat innovation.

For example, when I think of the future of remotely piloted systems operating from or with a carrier, I envision a future that has a Joint Strike Fighter pilot with three unmanned wingmen.

Question: One capability which fifth generation systems have brought to the fight is the capability of the aircraft to operate at great distances from one another.

This is a key enabler of better combat capabilities in the extended battlespace.

How do you view this synergy?

Rear Admiral Manazir: With the fifth generation aircraft and their sensors and fused data you can cover a much greater swath of combat space than with legacy aircraft.

And as we sort through how to integrate unmanned systems with F-35s we will be able in a single operational unit cover significant combat space.

You are looking at exponential growth in coverage capabilities to inform the process of generating the combat effects, which you want in that extended battlespace.

And the growth in the ability to generate better target information will allow us to execute strikes within our rules of engagement.

The coming of the F-35 will help in this process.

We train our aviators in the Navy and the Marine Corps to be decision-makers, given the constraints.

A lot of times, we can’t apply the rules of engagement we’ve been given because we can’t identify that’s a bad guy, whether he’s on the ground or in the air.

With better fidelity of information at the forward edge of the battle, I can execute more rapidly as well.

Question: We are discussing the evolution of the sea base and its operational capabilities in the extended battlespace.

But what can be missed is the innovation already underway by the Marine Corps-Navy team with the Osprey reaching 10 years of operational life, the IOC of the F-35B into Naval Aviation and several other innovations already in place and underway.

We noted that when the Truman strike group went to sea recently, that the team put the strike group to sea in a much quicker turn around than planned.

Rear Admiral Manazir: The Truman did go to sea based on a planned surge cycle, deploying to deal with emerging combat needs and requirements.

The carrier presence number is a vetted, risk-based, posture and presence discussion, with the Navy, the Joint Staff and the Secretary of Defense.

We choose where and when to put our forces out there.

But when they go, they’re ready for any mission.

In short, while some are considering the anti-access, area denial challenge as the end of history for the sea services, the professionals are treating the challenge as the opening of new round of innovation for the operation of the sea services in the 21st century battlespace.

For a biography of Rear Admiral Manazir, see the following:

http://www.navy.mil/navydata/bios/navybio.asp?bioID=525

For our report on the Future of Naval Aviation based on our visit to Fallon, see the following:

https://sldinfo.com/the-evolving-future-for-naval-aviation/

And for an overview of lessons learned from the Fallon visit:

https://sldinfo.com/lessons-learned-at-fallon-the-usn-trains-for-forward-leaning-strike-integration/

For earlier interviews with Rear Admiral Manazir and Vice Admiral Moran:

https://sldinfo.com/admiral-manazir-on-the-impact-of-global-partnerships-for-deterrence-in-depth/

https://sldinfo.com/the-uss-ford-in-the-u-s-navys-future-enabling-the-distributed-force/

For our visit to the class of USN carriers, the USS Ford, see the following:

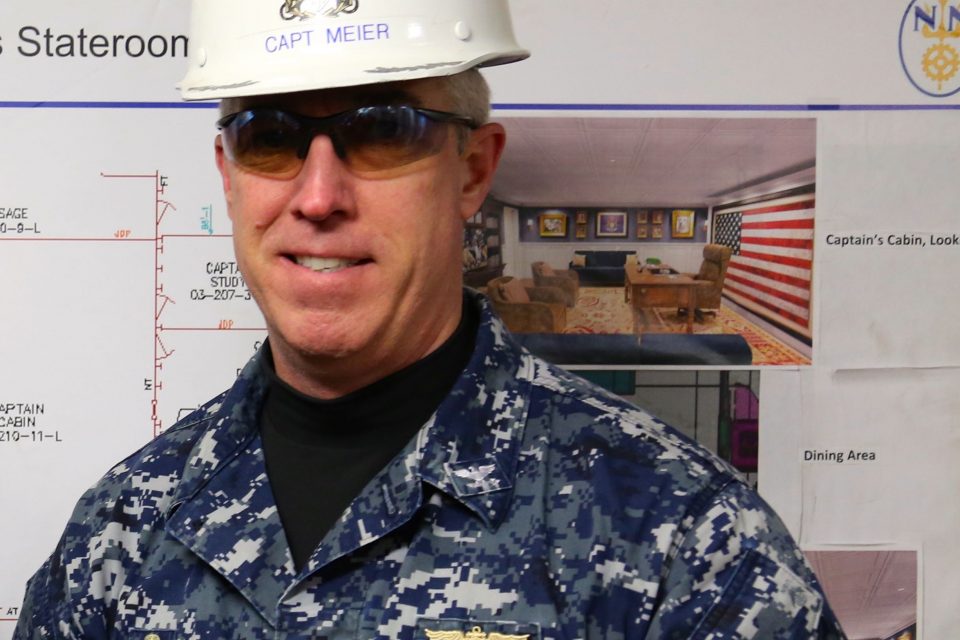

https://sldinfo.com/the-arrival-of-the-cvn-78-the-ships-captain-talks-about-the-way-ahead/

https://sldinfo.com/the-uss-gerald-r-ford-and-the-landing-and-take-off-launch-system/

https://sldinfo.com/crafting-the-gerald-r-ford-flight-deck-enlarging-the-operational-space/

The first slideshow highlights F-35Bs aboard the USS Wasp during sea trials in May 2015 and are credited to the US Navy.

The second slideshow are photos taken during our visit to Fallon Air Station and are credited to Second Line of Defense.

The third slideshow are photos taken during our visit to the USS Ford and are credited to Second Line of Defense.

The fourth slideshow are photos of the Truman strike group as they prepared to leave Norfolk earlier this month and are credited to the US Navy.