2017-04-20 By Colin Clark

WASHINGTON: America cannot apply Buy America provisions on a widescale basis and buy the best weapons, no matter how much President Trump and his team may feel otherwise.

It’s a simple as that.

All the competitors for the Air Force’s next-generation trainer, the T-X, include enormous amounts of foreign content, some including the aircraft. The biggest weapon system built for the US military, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, includes enormous amounts of foreign content.

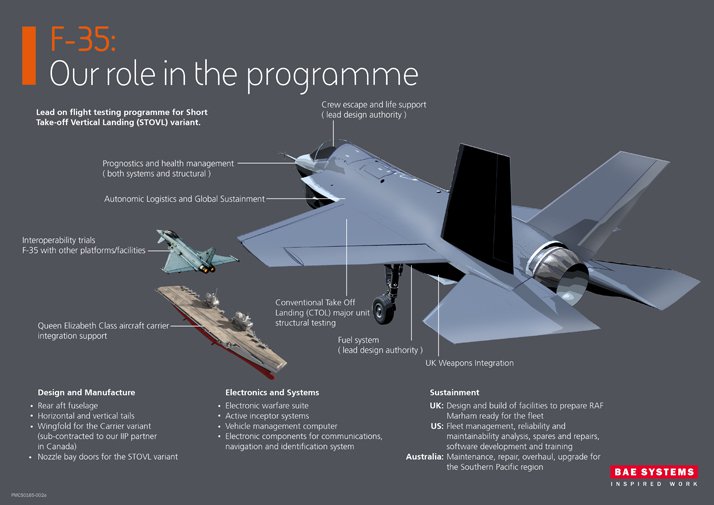

The F-35’s complex wiring bundles are done by a Dutch company. An Australian company builds vertical tailpieces. BAE, a British and American company, builds major portions of the plane.

Check out the graphic below by BAE Systems to see what they do. There’s even a Memorandum of Understanding between Australia, Denmark, Italy, Holland, Norway, Turkey, the UK and the U.S.A about the production, sustainment, and follow-on development of the F-35 that guarantees certain rights to the program’s original partner countries.

ANALYSIS

As those examples make clear, the world is really too interconnected to put America First in defense trade without harming American interests. American defense supply chains are inextricably tied to Europe, Australia, Japan and South Korea.

I don’t mention Canada because it is legally part of the US defense industrial base and is not subject to regulation. It was missed by many, but the 2017 National Defense Authorization Act added Australia and Britain to the US industrial base, so their companies also would not be subject to whatever the review finds.

One source familiar with the issue says Britain and Australia were added to fend off the worst effects of a Buy America crackdown that was already being discussed.

The global nature of America’s defense industrial base is the bedrock on which President Trump’s move to consider applying Buy America provisions to the Defense Department will probably crack. The Executive Order, signed Tuesday in a lackluster ceremony in Wisconsin, decrees a 150-day review requiring agencies asses how well they follow Buy American laws and decide whether they are issuing too many waivers.

Australias first F-35A Lightning II aircraft 01 and 02 on transit to the Australian International Airshow in Avalon. The Australian Defence Force is proud to be part of the 2017 Australian International Airshow, with displays showcasing the latest military aviation assets and technology.

Australias first F-35A Lightning II aircraft 01 and 02 on transit to the Australian International Airshow in Avalon. The Australian Defence Force is proud to be part of the 2017 Australian International Airshow, with displays showcasing the latest military aviation assets and technology.

Also, the Commerce Secretary of Commerce and the United States Trade Representative will consider the World Trade Organization Agreement and related documents to decide if they are cramping our ability to Buy American.

Here’s the only mention of defense in the EO: “In order to promote economic and national security and to help stimulate economic growth, create good jobs at decent wages, strengthen our middle class, and support the American manufacturing and defense industrial bases, (emphasis added) it shall be the policy of the executive branch to maximize, consistent with law, through terms and conditions of Federal financial assistance awards and Federal procurements, the use of goods, products, and materials produced in the United States.”

Rep. Duncan Hunter’s father tried to push Buy America provisions when he presided over his first National Defense Authorization Act.

It was a bad idea then, agreed everyone from Sen. John Warner, then chairman of the Senate Armed Services, to a senator named John McCain, the powerful Aerospace Industries Association, and a host of analysts and other lawmakers.

I know because I covered that debate.

Hunter and his few legislative allies lost that fight, utterly and completely — outmaneuvered and out-argued and, well, just out-thought.

A fellow named John Hamre, then Deputy Defense Secretary and now head of the hefty Center for Strategic and International Studies, commissioned a Defense Science Board study on globalization published in December 1999 that everyone involved in this debate needs to read as a primer.

The estimable Don Hicks, former Defense Undersecretary for research and engineering, wrote the report, with much help from international defense consultant Frank Cevasco and a host of others, including gentlemen named Ash Carter, Frank Kendall and Bill Schneider (who had the unique perspective of having served at the State Department and on the Defense Trade Advisory Group, of which he is still a member).

The most basic tenet of the DSB report:

“DoD once depended upon, and could afford to sustain, a dedicated domestic industrial base for the development, production and provision of its equipment and services. Today, the ‘U.S. defense industrial base’ no longer exists in its Cold War form. Instead, DoD now is supported by a broader, less defense-intensive industrial base that is becoming increasingly international in character.” That has only accelerated, as Carter made clear by creation of the DiUX network, the Rapid Capabilities Office and other innovation initiatives he championed while SecDef.

“The complex and often politically motivated statutes underlying the FAR and DFARS often restrict DoD’s ability to purchase some foreign products or products containing certain foreign material. Many of these (Buy America) statutes were be designed to protect the U.S. defense industrial base and U.S. suppliers of certain commodities from foreign competition.” (Our shipbuilding industry is a particularly intriguing example, I note.)

The report notes the persistence of Buy America pressure and makes clear the authors think such restrictions were something to be overcome, not embraced: “Attempts to increase DoD’s waiver authority have received limited political support because of the powerful constituencies represented in the governing statutes. On the positive side, however, most defense trading partners, including most NATO countries and selected others, have reciprocal procurement agreements with the U.S. Government that result in a waiver of the Buy American Act of 1933. The United States has such agreements with 21 countries and is in various stages of negotiations with several others, including some of the new NATO partners.”

If anything, the trends identified in the 1999 globalization report have only accelerated. Trying to redirect the flow of technology, capital and innovation is only likely to slow things down, add costs, deny us crucial technology and, perhaps most importantly, really irritate our close allies.

http://breakingdefense.com/2017/04/buy-america-again-sigh/

Republished with Permission of the Author.

Editor’s Note: This is an element of the turning point facing President Trump.

Either he wishes to invest in legacy systems or accelerates buying the new platforms and transforming the force into a truly world class high intensity fighting force.

And to do that Buy America poses barriers which simply make no sense and will add unnecessary costs to a force already having difficulties to accelerate transformation.

And indeed our closest allies are working with an operating the SAME new platforms which we are and we are in the process of learning together how to operate those systems in a fundamental defense transformation process.

And already we have dragged our feet because of past failures to grasp what foreign technologies even Americanized can deliver.

Why are the Aussies operating advanced battle management systems and tankers and we are not?

Why do the Brits deliver an advanced closed proximity weapon in combat systems which is the weapon of choice in the battles in the Middle East (Advanced Brimstone) and we do not?

Protectionism does not make sense in the face of allied global supply chains and cross learning.

We need to get on with accelerated modernization and not wallow in the past.

Indeed, instead of protecting military depots for a 20th Century military, we need to get on with 21st century global sustainment systems.

Buy American or lead global military transformation for a cutting edge US military.

The choice is stark and real.