By Robbin Laird

Part of the defense rethinking going on in Australia involves finding ways to enhance a sustainable fifth generation force.

Building out a lethal and effective offensive-defensive force, which can expand the perimeter for the defense of Australia and provide for allied extended deterrence, is a core focus of ADF modernization.

To do so in a crisis management situation needs a serious look at how long Australian operations could be sustained if a determined adversary sought to disrupt imports into Australia to support a modern society and a modern combat force.

The sustainment issue could be solved in part by enhanced domestic manufacturing capabilities and sustainment approaches, such as the projected shipbuilding effort or the F-35 regional support hub.

But clearly, there is an opportunity as well to build out manufacturing in Australia and with the ranges and potential workforce augmentations, missiles and unmanned air vehicles would be a clear area of interest, not just for Australia but for its partners as well.

As a member of the F-35 global enterprise, there is a clear global partnering opportunity whereby the Australians could do “a Konigsberg” and build missiles or related capabilities for themselves but in a way that makes them a natural partner with other key F-35 partners.

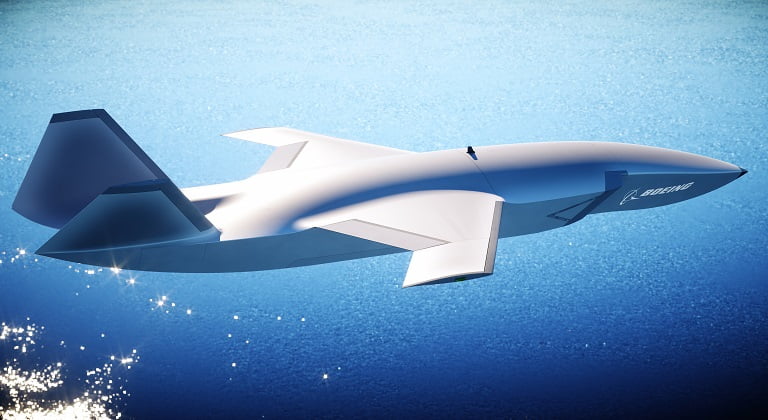

The recently announced “loyal wingman” program could be a case in point.

To be clear, the amount of money being discussed at the program launch at Avalon makes it, in the words, of a senior Australian strategist “a PR stunt.”

What he was focusing on was a key reality – the money being proposed could hardly achieve a program of record.

But one way to look at it might be to see an Australian effort to leverage their position geographically and in terms of training ranges to provide a foundation for several partners to come and to build out an Australian-based test, development and manufacturing capability.

It is clear that already fifth generation led training in the United States is extending the range of training – quite literally – and it will be virtually impossible for European and Asian F-35 partners to do such training without the geographical scope that Australia provides.

If we take a look at the proposed loyal wingman program, a key element is affordability and the expectation that these are assets which can be consumed in a combat scenario, more like weapons than airplanes.

And to get a low cost, it is clear that the wingman will not be an organic festival of advanced sensors, C2 or other features.

It will be a plus up in mass for what Secretary Wynne has called for in terms of ‘the wolfpack.”

Shaping the Wolfpack: Leveraging the 5th Generation Revolution

But some of the analyses surrounding the proposed program suggests that this will be an asset which can provide the tip of the spear into contested airspace or fly with legacy aircraft in a way whereby the legacy combat asset somehow has thinking capabilities which they simply do not have.

Clearly, as a low cost wingman is developed modifications to systems like Wedgetail or to tanker could occur to make them adjuncts to an operation, and as one considers the range of combat scenarios they could complement.

But the management capability onboard the mother ship so to speak is a key consideration of what will fly with it to make for an effective combat team.

One Australian enthusiast for the program highlighted what he sees as the contribution of this program to Australian sovereignty.

“We should now concentrate our efforts on breaking down barriers between further technological and industrial co-operation so we can build a sustainable sovereign defence industrial capability.”

Makes sense, if you are willing to invest significantly greater money in the program; but if it is a leveraging effort, then it is certainly conceivable that American, Japanese, and European F-35 partners would invest.

But it is also crucial to keep in mind the program’s limitations if it is to be a disposable lower cost asset.

The Australian analyst made a core point which he then seems to forget later in his analysis.

“The idea is that F-35s will be tasked with entering dangerous environments, relying on stealth and electronic warfare capabilities to survive, while spotting targets for lower-tech unmanned systems, like the new RAAF-Boeing drone, and non-stealthy fighters that remain outside the range of adversary defences.”

This statement is good up to a point; but the F-35 is a multi-domain air combat system with a brain big enough to work combat teaming with “slaves” in the wolfpack.

This is not true of 4thgeneration aircraft.

“This “loyal wingman” will be paired with fourth-generation manned aircraft such as F-18s and will likely act as decoys, scouts and communication relays. Eventually they may play a “bomb truck” role, carrying additional missiles and ordnance for both air-to-air combat and other strike missions.

“The largest benefit of these systems will be to beef-up its mass, or the amount of presence and firepower it will be able to project across the region against large numbers of adversary aircraft.

“A single F-18 with four to six autonomous wingmen in tow would be better able to survive, while being more lethal and numerous, multiplying its impact.”1

The problem with this is that a legacy aircraft like the F-18 will have a difficult enough time to survive without trying to manage “slaves” in tow.

If we return to the sovereignty bit, it is clear that if the loyal wingman program is a trigger to investment and engagement by the USAF and the RAF and others in leveraging the test ranges and future training facilities in Australia, this could well be a viable program.

But certainly not one for the amount of money being put on the table currently.

The demonstrator is being developed under the Loyal Wingman Advanced Development Program, which is being supported by A$40 million ($28.5 million) over four years in Australian government funding and by Boeing as part of its A$62 million investment in research and development in Australia in 2018.

The other limitation is clearly the current industrial capacity in Australia.

Boeing Australia has a modest industrial footprint in Australia, which might be considered seed corn but clearly not the kind of workforce and industrial facilities which will require a significant investment and build out.

Put in blunt terms: the loyal wingman could be part of enhanced Australian sovereignty and a trigger for global industrial partnering with Australia as a launch point rather than an importer.

But there is much work to do to make it so, to use the words of Captain Piccard.

Editor’s Note: After publication of the article, a senior Australian analyst provided some updated information with regard to the program.

The price quoted is only for the development of the first three prototypes.

Boeing has what was left of the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation (CAC) and the Government Aircraft Factories (GAF) which produced their own designs in the 80s and early 90s.

It’s now Boeing Aerostructures.

BAE have the autonomous brains to the system, which they produced for Tarinis, and there are no hydraulics in the system only electrics.

They are designing it to a price point.

The Future is Now: The RAAF & Boeing Australia Build F-35’s Unmanned Wingman