By Robbin Laird

During my recent stay in Australia in April 2019, I had the chance to meet with RADM Lee Goddard, Commander of the Maritime Border Command. His command oversees the operational side of ensuring maritime security for Australia.

Because Australia has no land borders, dealing with challenges like migration, drug smuggling and a variety of gray zone threats, the Maritime Border Command is a major player in operations to ensure Australian sovereignty on its borders.

It does so by a whole of government approach, which includes the ability to use defense assets as a key part of its operational approach. It really is designed to provide for integrated operations to try to optimize Australian security, in a very challenging environment.

The challenge simply starts with how extensive the sea borders are around Australia. We focused in our meeting on the Northern waters and the challenges associated with those waters. But the broader picture is even more daunting in terms of surveillance and determining paths of action.

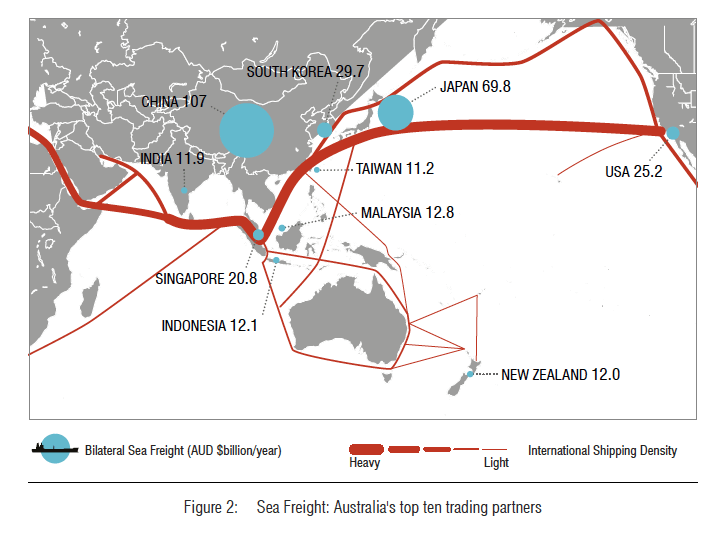

The reach North to New Guinea is where Australia almost reaches the land of a neighboring country. To the North is a key SLOC where significant trade comes into Australia, and to the West are the Malaccan straits.

We discussed challenges associated with the Lombok Strait, the strait connecting the Java Sea to the Indian Ocean, and is located between the islands of Bali and Lombok in Indonesia. The Gili Islands are on the Lombok side.

According to Wikipedia:

Its narrowest point is at its southern opening, with a width of about 20 km (12 miles) between the islands of Lombok and Nusa Penida, in the middle of the strait. At the northern opening, it is 40 km (25 miles) across. Its total length is about 60 km (37 miles). Because it is 250 m (820 feet) deep[1] — much deeper than the Strait of Malacca — ships that draw too much water to pass through Malacca (so-called “post Malaccamax” vessels) often use the Lombok Strait, instead.

The Lombok Strait is notable as one of the main passages for the Indonesian Throughflow that exchanges water between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean.

The importance of this strait and the other straits coming into Australian waters is determined both the need to protect Australian territory and the security and safety of its maritime trade.

To provide for Australian maritime security, the focus has been upon three strategic directions.

First, the Australian government has a very clear set of regulations and laws governing immigration and approaches to dealing with security at sea.

As Rear Admiral Goddard put it: “I can act on suspicion; which allows us to be proactive in dealing with threats.”

Second, the force is organized as an integrated one, so that new capabilities coming into the ADF, like the P-8, Triton, Offshore Patrol Vessels and new frigates and other Australian Border Force assets can be leveraged as necessary for operations.

Operation Resolute is a combined force approach to providing for perimeter defense and security of Australia.

As it was put on the Royal Australian Navy website:

Operation RESOLUTE is the ADF’s contribution to the Whole-of-Government effort to protect Australia’s borders and offshore maritime interests.

It is the only ADF operation that currently defends the Australia homeland and its assets.

The Operation RESOLUTE Area of Operations covers approximately 10 per cent of the world’s surface and includes Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone which extends up to 200nm around the mainland. Christmas, Cocos, Keeling, Norfolk, Heard, Macquarie and Lord Howe Islands also fall within the Operation RESOLUTE boundaries.

Commander Maritime Border Command (MBC) is the overarching operational authority that coordinates and controls both Defence and Australian Border Force assets from his headquarters in Canberra.

Maritime Border Command is the multi-agency taskforce which utilises assets and personnel from both the Australian Border Force (ABF) and the Australian Defence Force (ADF) to safeguard Australia’s maritime jurisdiction. Its maritime surveillance and response activities are commanded and controlled from the Australian Maritime Border Operations Centre in Canberra.

We discussed some of the new technologies which allow for greater SA over the maritime zones, but of course the challenge is to turn SA into ways to influence actors in the maritime zone.

“It does no good just to know something is happening; how do we observe but let the bad guys know we see them and can deal with them?”

Third, obviously IT and C2 are key elements of bringing the force to bear on the threats.

But doing so is a significant challenge, but one where new technologies and new capabilities to leverage those capabilities for decision making clearly are helping.

This is a work in progress where the Commander works with several government departments as well as industry to deliver more effective intelligence to determine where the key threats are to be found and being able to deploy assets to that threat.

Rear Admiral Goddard underscored that developments in the IT and decision tools area were already helping and would be of enhanced performance in the period ahead.

“With some of the new AI tools we will be able to process information more rapidly and turn SA into better decision making.”

Fourth, obviously this means working closely with partners in the region, such as Malaysian, Indonesia and the Philippines and shaping ways to operate more effectively with one another.

There are several examples of Australia expanding its working relationships with neighbors, which means as well finding ways to share information and to train together for common actions.

A challenge being posed by the Navies in the region is that they are clearly are generating what have been called gray zone threats.

This is why the Command is really part of more broadly understand security capability within an overall national crisis management effort.

And as the threats change or challenges change, the capabilities for the Command working with the ADF will need to change as well.

Editor’s Notes:

The description of the Command as provided on their web page is as follows:

Additional information was then provided as follows:

Deter, prevent, detect and respond to civil maritime security threats

Maritime Border Command uses an intelligence-led, risk-based approach to combat the civil maritime security threats within the Australia’s maritime domain.

Our dedicated Intelligence Centre collects, processes, integrates, evaluates, analyses and interprets information and intelligence to generate civil maritime domain awareness.

We use surveillance and identification systems such as the Australian Maritime Identification System to detect, risk assess and track vessels operating in or approaching our maritime zones.

We then tailor our operations to combat these threats with the support of surface and air assets.

Contribute to Operation Sovereign Borders

Operation Sovereign Borders is a military-led, multi-agency operation to secure Australia’s borders, combat maritime people smuggling and prevent deaths at sea.

We detect and intercept people-smuggling vessels that approach Australia, and carry out on-water operational responses including boat turn-backs where safe to do so.

Work with partner agencies and international counterparts

State, territory and Australian Government partner agencies guide our operations. Together, we work to provide a whole-of-government response to key civil maritime security threats.

We also collaborate with international intelligence and law enforcement authorities through information sharing, joint patrols and other cooperative arrangements.

Engage with industry

Maritime Border Command engages with industry by communicating with industry to advise of maritime actions that may impact on their businesses and advising of appropriate preventive security measures.

By complying with preventive security measures, the maritime industry also contributes to the ongoing safety of our maritime domain.

https://www.abf.gov.au/about-us/what-we-do/border-protection/maritime

The USCG Experience and Parallel

My own observations with regard to the challenges for the way ahead come from working with the USCG.

As the gray zone challenges become more dominant in the maritime security environment, a key challenge is getting the military and civilian sides of how to deal with the challenge.

It becomes less a law enforcement function and more one that is a crisis management challenge where various types of authorities need to be exercised.

And this has certainly been a challenge for the US in which we can use military force or do law enforcement but we are not as good as we need to be in terms of being organized for what falls in between.

And that is precisely the area that is growing in strategic importance and significance

The structure which the Australians have built with the Maritime Border Command can provide a good focal point for sorting out good ways to shape 21stcentury crisis management capabilities; but it too will be a challenge for them as well.

An illustration of who the interagency process works in Australia to deliver maritime security was provided in this February 27, 2018 article on joint patrol operations off of the East Coast of Australia.

Commander MBC Rear Admiral Peter Laver said the patrol provided an opportunity to gather intelligence and work closely with our partners, stakeholders and the broader community to inform them about what suspicious activity to look out for and how to report it.

“Local knowledge is a great source and is perfectly placed to recognise signs of illegal fishing, prohibited imports and other criminal attempts to breach our borders,” Rear Admiral Laver said.

“Our officers spend weeks at a time at sea, quite often out of view of the general public, but patrols like this allow us to demonstrate that no matter where you are around the Australian coast, we are never far away.”

ADV Cape Fourcroy Commanding Officer Lieutenant Ken Brown said the multi-agency patrol was a great way to foster collaboration and his crew was ready to tackle any civil maritime security threat.

“The opportunity to share our intelligence and operational expertise is invaluable to our work and increases Australia’s capability to disrupt illegal activity in our waters, whether it be foreign fishing, drug smuggling or any other civil maritime security threat,” Lieutenant Brown said.

“This was a great chance to showcase what we do and assure the Australian people that we are out on the seas, patrolling and protecting our waters and securing Australia’s borders.”

AFMA’s General Manager of Fisheries Operations, Peter Venslovas, said that collaboration between Australian authorities is paramount to ensuring the future of Australia’s marine life.

“AFMA works closely with other government agencies including ABF and the ADF on activities like deploying fisheries officers on joint patrols to further our work in deterring and combatting illegal foreign fishing,” Mr Venslovas said.

“Protecting the marine environment from threats of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing activity is one of our main priorities.”

The vessel departed Cairns on 8 February 2018 and has visited ports including Bundaberg, Coffs Harbour, Sydney, and Brisbane.

https://www.afma.gov.au/joint-agency-patrol-targets-east-coast-maritime-threats

Editor’s Note: In an interview we did with Rear Admiral Day of the USCG in 2010, he laid out the nature of the situational awareness effort to shaping a successful engagement effort:

SLD: Could you provide us with an overview of C4ISR works in the USCG?

Admiral Day: Let’s talk about how C4ISR is used in support of Coast Guard missions. And what changes have occurred—drastic changes—in the last 10 years and the drastic changes that are going to be needed even in the next five. These changes may or may not occur, because they may or may not make the funding threshold. In most cases right now, they are not going to make the funding threshold.

SLD: C4ISR is essential for a modern Coast Guard to function. Although ethereal to many, the glue, which holds the platforms together, is clearly C4ISR. Could you provide a sense of the shift in performance enabled by the new C4ISR systems?

Admiral Day: Let’s talk about just the Eastern Pacific drug mission. Let’s just use that as an example. In the old days, we literally went down there and bored holes in the water, and if we came across a drug vessel, it was by sheer luck. It might be on a lookout list, and we might happen to see it. Let’s fast-forward now to the 2000s and what we’ve started being able to do.

By being able to fuse actionable intelligence, and not only that, but intelligence communicated at light speed. So now, we’re to the point where we’re telling a Cutter to go point A, pick up smuggler B with load C. And we’re doing that in real time with delivery of a common operational picture, which has been fused with intelligence. That was unheard of 10 years ago.

SLD: So you’re contrasting on the one hand the hunt-and-peck method or the stumble across by chance method, versus having enough information to actually target a problem.

Admiral Day: And not only that, taking information from a wide range of intelligence sources and agencies that we can participate with and bringing it in and fusing it. And leveraging all those tools and being able to process that information to figure out anomalies and actually start doing these interdictions.

SLD: Could you contrast your experiences as a young sailor and a sailor doing the mission now?

Admiral Day: Well, it’s a whole different framework. The framework is shaped by most of the fusion of the information which is being done off the Cutter. The Cutter is merely a delivery mechanism for capability; the Cutter is now the point of the spear. It has enabled the networks and all the systems back ashore at our Command Centers and our Intelligence Coordination Centers, whether it’d be from Joint Inter-Agency Task Force (JIATF) South or whether it’d be our own.

This ability to communicate that to them in real time allows to literally send them a common operational picture: the X is already on your radar screen, and you say go to that target.

SLD: So the difference here is that in the first case, you’re just throwing a spear out to the ocean.

Admiral Day: And hope you hit something.

SLD: And where you land, hopefully somebody’s near the spear. So the way you’re thinking is we have this grid over an area, and your platforms are the customers, so to speak, or the enforcers.

Admiral Day: Absolutely. They’re the operational element that we are producing information for their mission execution.

SLD: The C4ISR systems are essential to changing the calculus of operations as well as enabling the USCG in its joint role as well?

Admiral Day: Yes. For example, in the eastern Pacific, that’s done in JIATF South, which is an interagency task-force, they’re doing the lay-down based on the information that they’ve got.

They’re getting the intelligence feeds as well we’re getting intelligence feed and feeding into it.

Rear Admiral Lee Goddard was promoted to his current rank and became the Commander Maritime Border Command in February 2019. Prior to this he was seconded as a Branch Head to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Lee Goddard joined the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) in 1987 from Melbourne through the Australian Defence Force Academy where he completed his degree studies graduating with a Bachelor of Science in 1989. In his final year he was appointed as the first Naval Academy Cadet Captain and was awarded the RSL Sword of Leadership on graduation. In the following year while completing Seaman Officer training at the RAN College (Jervis Bay) in 1990 he was appointed College Captain and awarded the Queen’s Medal.

Throughout his career he has served at sea in Australian, Canadian, Malaysian and US Navy warships, and on operations in the Middle East. He gained his Bridge Watch-keeping Certificate in early 1992 while serving on exchange with the Canadian Navy, in HMCS Yukon based in Victoria, British Colombia. Later in 1993-1995 he served as a Watch/Executive Officer onboard Australia’s national tall ship STS Young Endeavour and he has been posted overseas to Malaysia and Bahrain.

In 1996 he completed the RAN Principal Warfare Officer’s course where as dux he was awarded both the Sydney-Emden prize and the RAN Sword of Excellence. He was a member of the commissioning crews of the ANZAC Class frigates HMAS Arunta (Warfare Officer) during 1997 – 1999 and HMAS Stuart (Executive Officer) during 2001 – 2003. During 2006-2008 he commanded the ANZAC Class frigate, HMAS Parramatta, and the ship was awarded the Duke of Gloucester Cup in late 2008. Lee Goodard was awarded the Conspicuous Service Cross (CSC), on Australia Day 2007, for service as the commander operations in the maritime component of Joint Operations Command.

Following on from his first sea command in 2008 he was appointed Commander Sea Training.In 2009 he was posted as an inaugural member of the ‘New Generation Navy’ Team, as the Deputy Director Transformation & Innovation working closely with the Nous Group that reported directly to the Chief of Navy.

He was then selected to attend the US Naval War College in Newport Rhode Island, where he joined the Naval Command College, graduating in June 2010 and was awarded the War College’s International Leadership Prize. He was subsequently asked to remain at the War College as an International Fellow, teaching within the Department of Strategy and Policy at the Masters level.

On his return to Australia in early 2011 he was appointed as the Director Military Strategic Commitments at the Australian Defence Headquarters, working within the strategic level of Defence and across Government. He returned to sea in late 2012 to assume command of the upgraded Anzac Class warship HMAS Perth. On promotion to commodore in late 2014 he assumed the role of Commander Surface Forces.

Rear Admiral Goddard was awarded a Master of Arts (International Relations) in 1996, is member of the Australian Naval Institute council and has previously served as councilor with the Australian Institute of International Affairs. He has contributed to a range of professional and academic journals focused on international affairs and security issues.

The featured photo shows then Commodore Surface Force, Commodore Lee Goddard, RAN, speaking with Leading Seaman Marine Technician Candice O’Keefe in the Central Control Station during his visit to HMAS Canberra, Jervis Bay.

HMAS Canberra is the first of two Landing Helicopter Docks (LHDs), the largest ships ever built for the Navy.

The ship’s company is made up of 400 personnel from Navy, Army and Air Force.

HMAS Canberra was commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy in Sydney on 28 November 2014.