By Robbin Laird

In today’s world, full spectrum crisis management is not simply about escalation ladders; it is about the capability to operate tailored task forces within a crisis setting to dominate and prevail within that crisis.

If that stops the level of escalation that is one way of looking at it. But in today’s world, it is not just about that but it is about the ability to operate and prevail within a diversity of crises which might not be located on what one might consider an escalation ladder.

They are very likely to be diffuse within which the authoritarian powers are using surrogates and we and our allies are trying to prevail in a more open setting which we are required to do as liberal democracies.

This means that a core legacy from the land wars and COIN efforts needs to be jettisoned if we are to succeed – namely, the OODLA loop.

This is how the OODA loop has worked in the land wars, with the lawyers in the loop, and hence the OODLA loop.

The OODA loop is changing with the new technologies which allow distributed operators to become empowered to decide in the tactical decision-making situation.

But the legalistic approach to hierarchical approval to distributed decisions simply will take away the advantages of the new distributed approach and give the advantage to our authoritarian adversaries.

What we are seeing is a blending of technological change, with con-ops changes and which in turn affect the use and definition of relevant military geography.

In other words, the modernization of conventional forces also has an effect on geography.

As Joshua Tallis argued in his book on maritime security, the notion of what is a littoral region has undergone change over time in part due to the evolution of military technologies.

“Broadly speaking, the littoral region is the ‘area of land susceptible to military influence from the sea, and the sea area susceptible to influence from the land.’

“In military terms, ‘a littoral zone is the portion of land space that can be engaged using sea-based weapon systems, plus the adjacent sea space (surface and subsurface0 that can be engaged using land-based weapon system, and the surrounding airspace and cyberspace.’

“The littoral is therefore defined by the technological capability of a military, and as a result, the littoral is not like other geographic terms.”1

What is changing is that the force we are shaping to operate in the littorals has expansive reach beyond the presence force in the littorals themselves.

If you are not present; you are not present. We have to start by having enough platforms to be able to operate in areas of interest.

But what changes with the integrated distribute ops approach is what a presence force can now mean. Historically, what a presence force is about what organically included within that presence force; now we are looking at reach or scalability of force.

We are looking at economy of force whereby what is operating directly in the area of interest is part of distributed force.

The presence force however small needs to be well integrated but not just in terms of itself but its ability to operate via C2 or ISR connectors to an enhanced capability.

But that enhanced capability needs to be deployed in order to be tailorable to the presence force and to provide enhanced lethality and effectiveness appropriate to the political action needed to be taken.

This rests really on a significant rework of C2 in order for a distributed force to have the flexibility to operate not just within a limited geographical area but to expand its ability to operate by reaching beyond the geographical boundaries of what the organic presence force is capable of doing by itself.

This requires multi-domain SA – this is not about the intelligence community running its precious space- based assets and hoarding material. This is about looking for the coming confrontation which could trigger a crisis and the SA capabilities airborne, at sea and on the ground would provide the most usable SA monitoring. This is not “actionable intelligence.”

This is about shaping force domain knowledge about anticipation of events.

This requires tailored force packaging and takes advantage of what the new military technologies and platforms can provide in terms of multi-domain delivery by a small force rather than a large air-sea enterprise which can only fully function if unleashed in sequential waves.

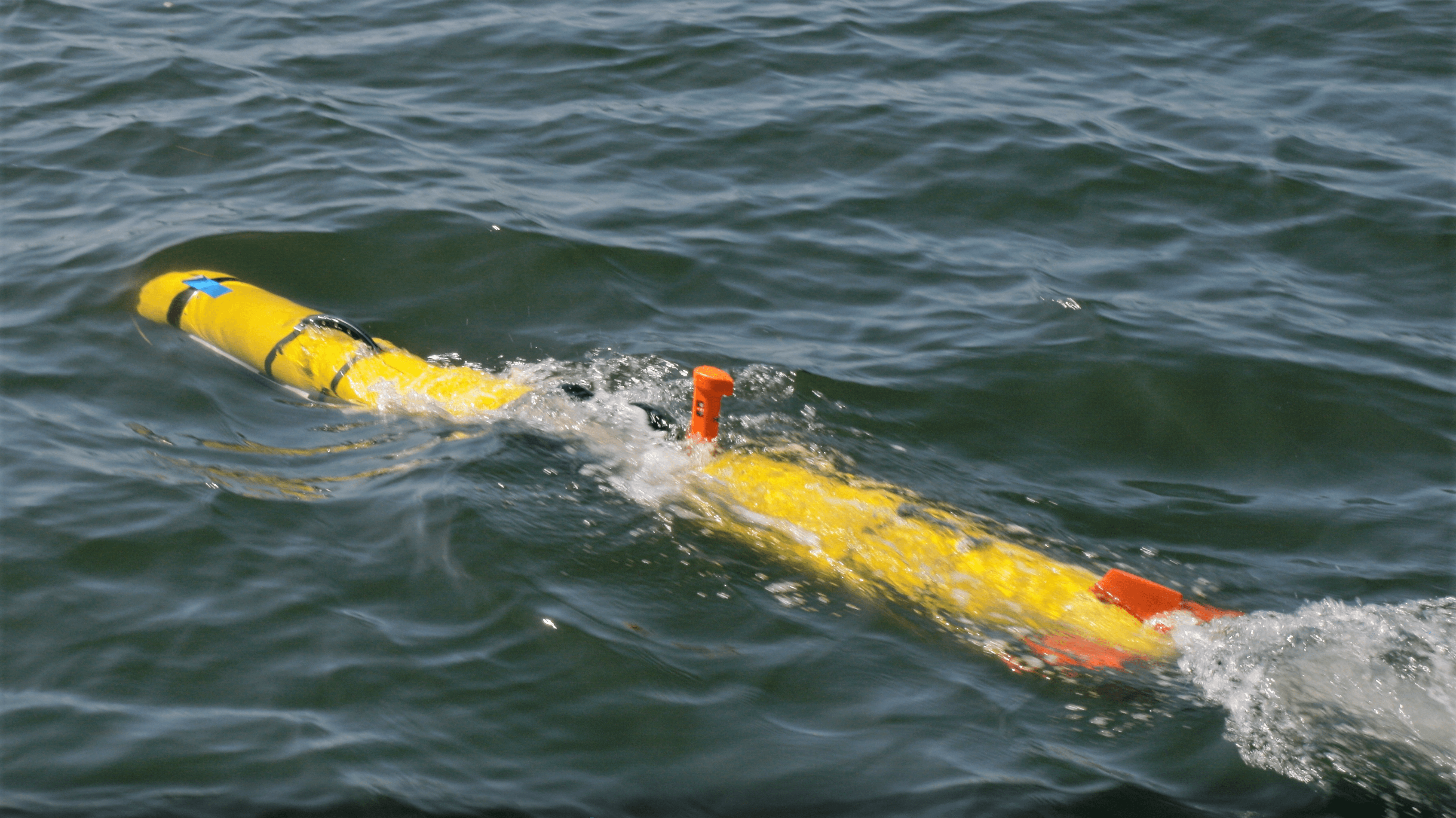

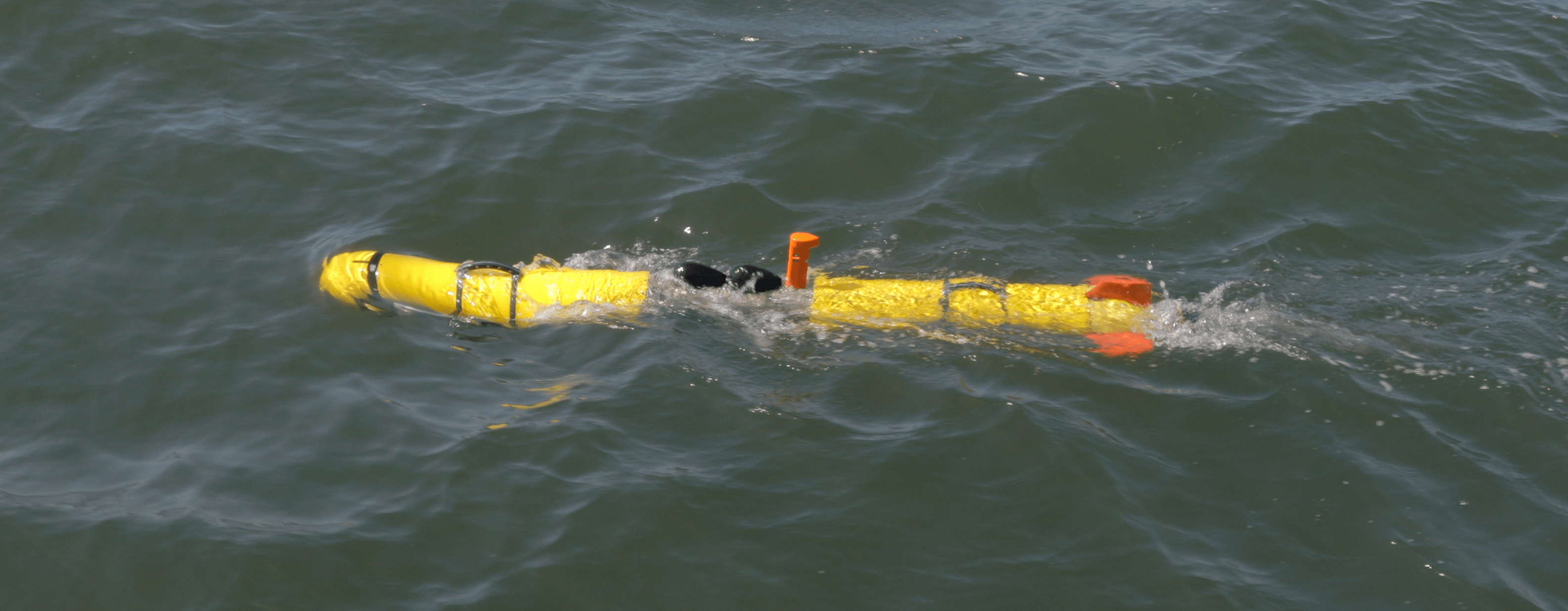

In the maritime domain, an evolving capability which will operate in concert with capital ships are unmanned maritime systems or remotes.

Such systems come in two forms: underwater unmanned systems and surface unmanned systems, which when the con-ops matures will work interactively with one another to extend the reach of the manned surface fleet to provide for perimeter defense via a flexible picket fence so to speak, and to provide a significant impact to the reworking of C2 highlighted above.

In many ways, the F-35 force package is directly forcing a significant revision of where D takes place in the OODA loop. Tactical decision making at the edge needs to be worked as the F-35 pushes decision making capability to the edge.

As that is worked through, the next phase will entail how remotes can provide not just SA and remote targeting capabilities, but share in the decision making with the humans in the loop.

For the Air Forces, this will be about sorting through how loyal wingman can work with manned combat air assets; for maritime forces it will be about how above and below sea remotes can be woven into the extended reach of a capital ship and become part of a force package, and, in turn, changing the nature of what a combat fleet looks like.

In other words, there are waves of learning how to work with remotes and to incorporate them into an integrated distributed force.

Over the next five years, we will see a significant presence of maritime remotes and as operational experience is gained, the next wave of learning will go from treating these as platforms adding to the capability of the fleet, to becoming core parts of an integrated distributed force with significant changes in the concepts of operations of the combat fleets as well.

During my visit to the Chief of the Royal Australian Navy’s Seapower conference which was held in Sydney from October 8th through the 10th, 2019, I had a chance to discuss with officers of the Royal Australian Navy as well as defense industry leaders the evolving maritime remote capabilities currently available and on the horizon.

One of those industry leaders I met with was Daryl Slocum of L3HarrisTechnologies.

He has been involved with maritime remote systems since his graduate student days and as head of the OceanServer program, is based in Massachusetts at the L3Harris facility located there. He was at the conference engaging with various Navies attending the conference to discuss the capabilities which L3Harris has in the maritime remotes area.

I took advantage of his presence to discuss more generally how one might understand how maritime remotes are developing and might develop in the future, and their role and contribution to the maritime combat force.

Slocum views maritime remotes as force multipliers.

As the durability of the systems evolves and they can operate at greater range and operate with greater loiter times, the core question is what the fleet commanders want these systems to do.

This means that the focus is clearly upon payloads, and how to take the information on these remotes generated by the various payloads and to get that information in a timely manner to the users in the combat fleet.

Right now, unmanned underwater systems can operate with a variety of payloads, the most significant of which can provide remote mapping and situational awareness.

As the capabilities to do onboard processing on the remotes ramps up, information can be processed on the platform and with the aid of evolving artificial intelligence can determine provide for information parsimony.

This means that the systems onboard the platforms as their capabilities evolve will be able to send core information to users highlighting threats and opportunities for the combat fleet.

And as the ability of the remotes to work with one another evolves, surface and subsurface remotes will be able to work together so that the communication limits imposed by underwater coms can be mitigated by surface remotes working as transmitters.

We discussed the impact of these projected capabilities on capital ship design.

It is clear that new capital ships need to have onboard processing capabilities and decision tools to be able to leverage what a deployed system of remotes might be able to deliver to that capital ship.

This means as well that maritime warriors will need to learn to work with thinking machines as decision making at sea will evolve as well.

Slocum highlighted that the Iver family of L3Harris underwater remotes were platform agnostic, which meant that they can work with a wide variety of users worldwide.

This means as well that they can focus on building a platform which is battery agnostic as well to incorporate changes in the evolution of battery capabilities, which are of course, crucial to durability, speed and range of the remotes.

We both agreed that is important to get these systems out of the labs and into the fleet to get the kind of operational experience necessary to drive innovation moving forward with essentially a software upgradeable platform.

Slocum indicated that they had this kind of relationship with the US Navy in San Diego as the US Navy gets read to tap into remotes as a key part of the counter mine mission.

As he described the goal of a remote platform which is payload agnostic:

“Today, I want to do a side scan mission; tomorrow, I might want to do an ISR mission; and the day after tomorrow, I might want to do a SiGINT mission.”

By having a small form factor platform, with a capability to operate with a diversity of payloads, the remote can be incorporated into a wide array of missions which can expand what the capital ship itself is capable of doing.

Indeed, the impact of remotes can expand what a support fleet can do.

There is no reason that a U.S. Military Sealift Command ship cannot incorporate remotes and expand the concept of what kind of support MSC ships can provide, beyond physical things such as fuel and supplies.

In other words, remotes can provide for con-ops diversification within the combat fleet, including the supply component of that fleet as well.

Clearly, such capabilities could provide significant enhancements with regard to perimeter defense in various ways, including masking what that remote actually is and what it is doing.

Currently, L3Harris has more than 300 Iver platforms operating worldwide, with 2/3 of them with military customers and 1/3 with civilian customers, including research centers as well.

We closed by discussing where the remote capabilities might be in five years’ time.

Slocum saw Iver as being able to operate for longer times, and taking onboard new payloads. He projected that onboard processing capability would take a leap forward which would lead to making more timely use of the data being collected by the remotes.

A key breakthrough point will be when remotes can make a decision about which data needs to be sent back home to the human decision maker.

Beyond the five year time line, Slocum saw that after working through operational experience in that time period, the ability of remotes to work together would become more mature.

And as that capability evolves, the entire reworking of the decision cycle will evolve as well.

In short, it is not just about remotes as a platform; they are being introduced at the same time as the military is undergoing a transformation to shape an integrated distributed force.

And for the maritime forces, remotes will provide a core capability to fleet enhancement.

Also see the following: