By Robbin Laird

Recently, I attended the Chief of the Royal Australian Navy’s Seapower conference being held in Sydney from October 8th through the 10th, 2019.

One of the sessions which I attended was a presentation by Cmdr. Paul Hornsby, Royal Australian Navy lead on autonomous warfare systems.

The presentation provided an overview on how the Australian Navy is addressing the development and evolution of remote systems within the fleet.

During my visits over the past five years in Australia and my time with The Williams Foundation, I have been impressed with the ADF and its efforts to build a transformed force.

The transformation process has been identified as building a fifth-generation force.

And within that effort, the significant modernization envisaged for the Australian Navy is focused on shaping a transformed maritime force as well.

As former Chief of Navy, Vice Admiral (Retired) Barrett put it in our interview earlier this year: “We are not building an interoperable navy; we are building an integrated force for the Australian Defence Force.”

The kill web approach was clearly what he is working from when he discusses force modernization for the Navy.

In this process of force transformation, the ADF is committed to a wide range of innovative roll outs to experiment in the evolution of its fifth generation con-ops.

This is why for a much larger force like the United States possesses, the Australians in their approach represent not just innovation for themselves but for the U.S. and other Australian allies.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the domain of unmanned maritime systems.

As Hornsby put it in his presentation: “We have no choice but to be leaders in this area.”

He underscored that the significant operational area which Australian forces need to patrol coupled with limited numbers of maritime platforms and manpower limits meant that the building, operating and integration of maritime remote systems in the fleet was an operational necessity for the Royal Australian Navy.

“We could not get enough help from remote systems and artificial intelligence.”

He argued that there was a cross-societal engagement with remote systems in Australia which the Navy could leverage as well.

He noted that Australia has been involved in allied exercises across the board in the remote systems area.

He laid out through the various exercises in the UK, Australia and elsewhere that his team has been fully engaged in cross learning with allies, and to do so in order to harvest the best and leave the rest.

He made a case for why Australia is a very important area for allies to work with the Aussies on remote innovations.

The conditions in Australia are challenging and paraphrasing Frank Sinatra: “If you can make it here, you can make it anywhere.”

I would argue that the current challenge facing the US and allies shaping an integrated distributed force is being able to make decisions at the tactical edge. Certainly, the introduction of the F-35 is providing a forcing function with this regard.

As allied militaries work their approaches toward shaping an integrated distributed force, and once they have forged approaches to make decisions at the tactical edge, they are then able to leverage what artificial intelligence operating in a network of remote systems, such as maritime remotes, can deliver to the combat force.

In other words, learning how to make decisions at the tactical edge with the fifth-generation force will allow for the next wave of innovation which AI-enabled remote systems decision making.

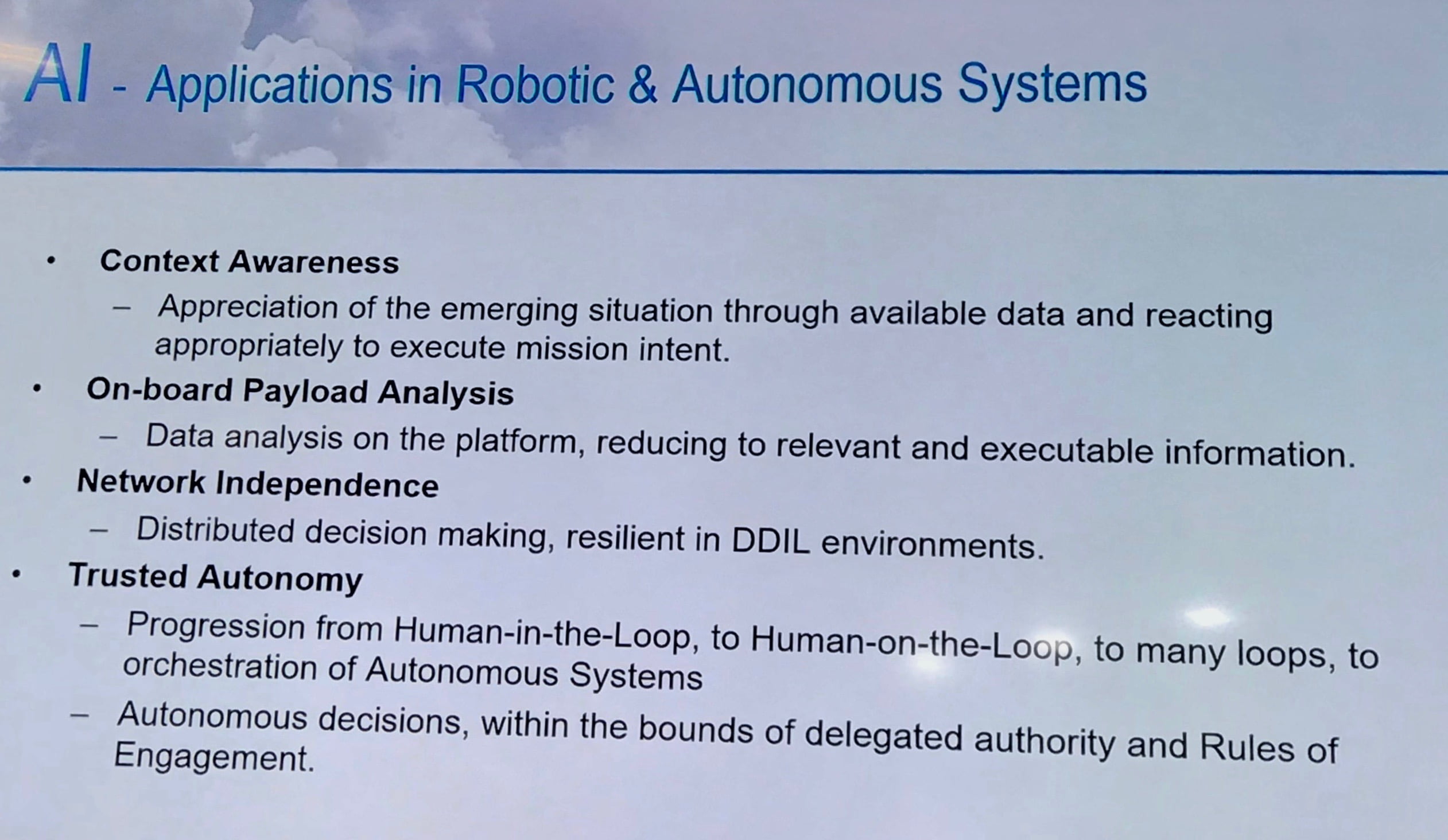

Cmdr. Hornsby underscored a number of key contributions of AI to the build out of a remote system distributed force.

The following graphic highlights the key aspects which he highlighted.

Key points are reaching a stage where the remotes can work with one another, underwater and above water, to provide SA to the battle commander; and to shape ways for the distributed system to assist and make decisions in something which really as way beyond the classic OODA loop.

When the machines are working OO and notably with AI then the focus is upon how to DA.

And even more to the point, humans and machines need to work the decision-making loop together and this requires signifiant learning on the human side for sure.

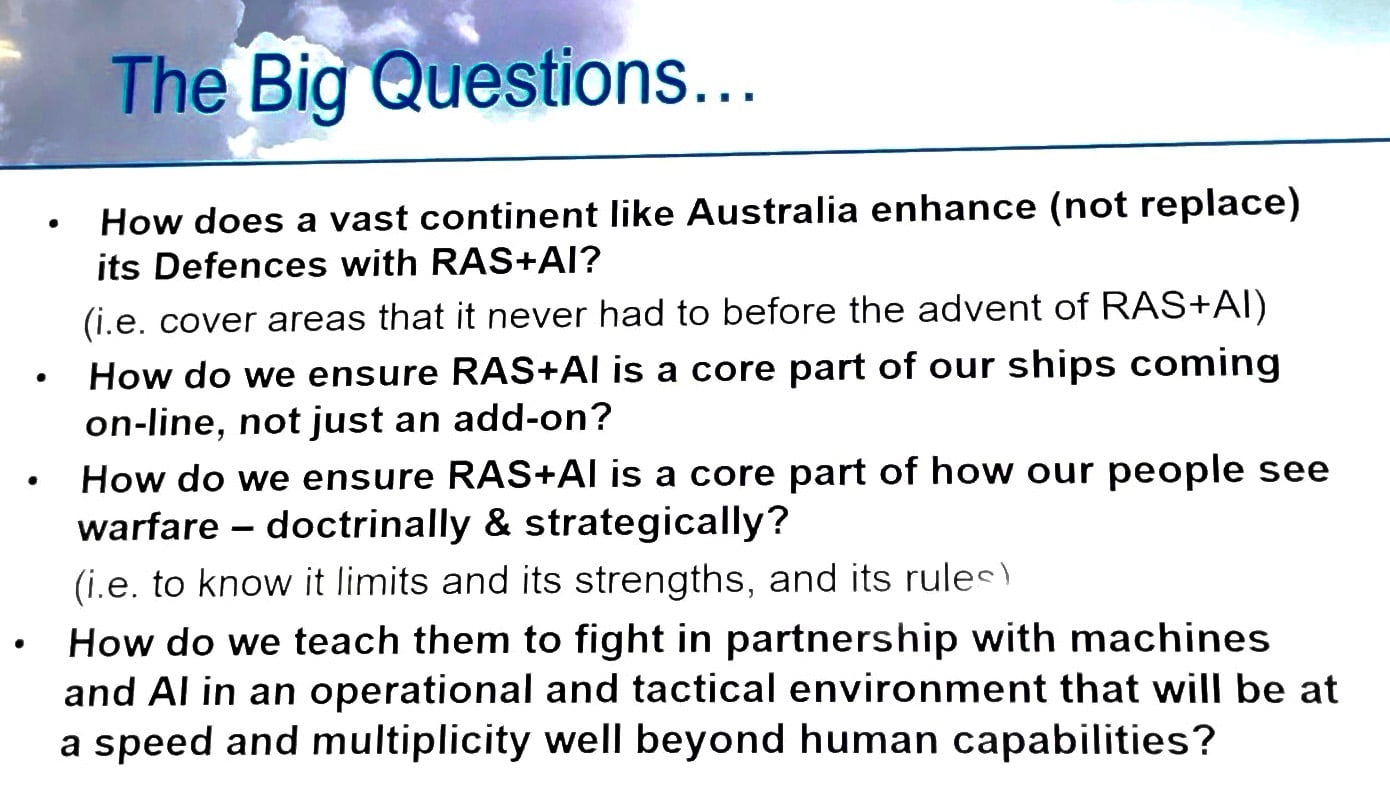

As he concluded his presentation, he framed a number of key questions which he argued needed to be addressed and ways ahead found to answer them.

It is often the case, that change is really about changing the nature of the questions which need to be answered, rather than finding new answers to older questions.

The following graphic lays out the core questions which he posed:

I would highlight one of those questions for a further comment– the need to design new combat ships from the outset to have the capabilities to operate with remotes.

This means that new platforms moving forward need to have data processing capabilities, personnel able to operate SA systems, an ability to include relevant remote platforms onboard as well as a range of platform payloads, and technicians onboard able to deliver sustainment to systems operating at a distance and over relatively long operational times.

In short, for Cmdr. Hornsby the future is now.

And I would add my own judgement – it is crucial to get some of these systems at sea in the operational force for these platforms and payloads will be transformed over time by operational input even more than R and D done by researchers alone.