By Robbin Laird

Last Friday, the US Navy and the Bell-Boeing team hosted an event in which the CMV-22B was rolled out.

The ceremonial delivery was held on February 7, 2020, but the week before the first aircraft had landed at Pax River for its final round of testing before going to the fleet next week.

The first CMV-22B deployment is less than a year from the initial delivery of the aircraft which means that from the 2015 initial funding for design work to the 2018 production contract, the aircraft will be operational within six years from contract to delivery.

Obviously, this means that the Navy has leveraged the many years of experience of the USMC and the USAF in operating, maintaining and upgrading the aircraft, to leverage a common asset, to get a new combat capability.

The aircraft is replacing the venerable C2 aircraft in the carrier onboard delivery role, but from the outset is designed to provide a wider set of roles, including search and rescue and support for Naval Special Warfare.

But this is just the beginning.

In a visit to San Diego the week before the ceremony, I had a chance to sit down with Vice Admiral Miller, the Navy’s Air Boss, to discuss the way ahead with naval aviation.

We will publish that full interview soon, but the Air Boss highlighted a significant shift from a focus on the integrated air wing to the integratable air wing.

The US Navy over the next decade will reshape its carrier air wing with the introduction of a number of new platforms. If one lists the initial operating capabilities of each of these new platforms, and looked at their introduction sequentially, the air wing of the future would be viewed in additive terms – what has been added and what has been subtracted and the sum of these activities would be the carrier air wing of the future.

But such a graphic and such an optic would miss the underlying transformation under way, one which is highly interactive as well with the transformation of its core sister service the USMC or of the multi-domain drive being pursued by the USAF. And one would totally miss the interactivity of the transforming air wing with the transformation of our core allies.

One clearly needs a different optic or perspective than simply taking an additive approach.

And in effect, what is underway is a shift from integrating the air wing around relatively modest and sequential modernization efforts for the core platforms to a robust transformation process in which new assets enter the force and create a swirl of transformation opportunities, challenges and pressures.

How might we take this new asset and expand the reach and effectiveness of the carrier air group?

How might it empower maritime, air and ground forces as we shape a more effective integratable force?

To give an example, the U.S. Navy is replacing the C-2 with the CMV-22 in the resupply role.

But obviously, with what the USAF and USMC have done and are doing with the Osprey, the Navy would be foolish indeed simply to think in terms of strictly C-2 replacement lines and missions.

So how should the Navy operate, modernize and leverage its Ospreys?

For Miller, the initial task is to get the Osprey onboard the carrier and integrated with its initial air wing operations.

But while doing so, it is crucial for the Navy to work the integratable piece, namely, what can an expanded aperture for the Osprey working within the CAG provide for the integratable air wing?

For Vice Admiral Miller, he is looking for the first five-year period in operating the CMV-22 for the Navy to think through the role of the Osprey as a transformative force, rather than simply being a new member of the carrier air wing.

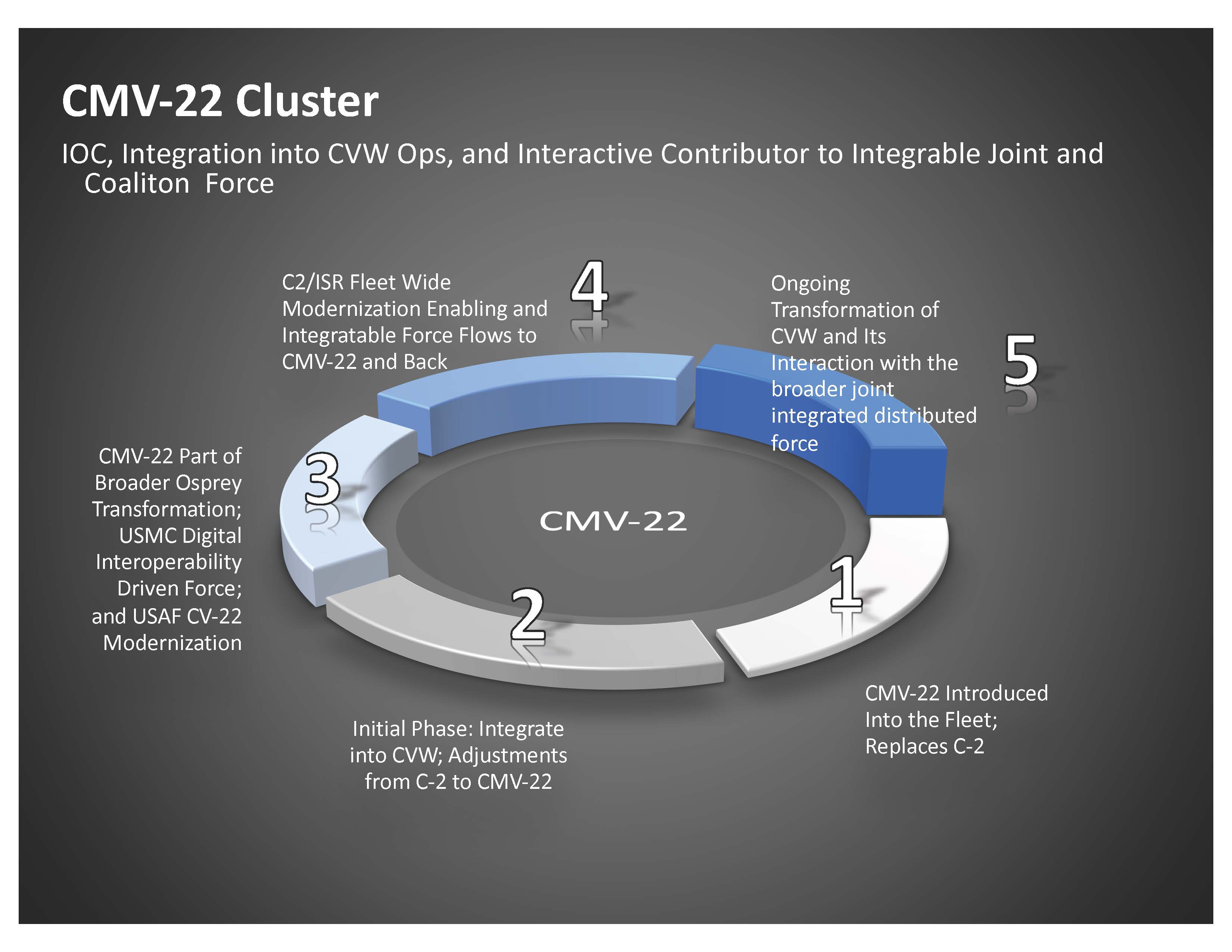

Hence, one can look at the CMV-22 innovation cluster in the following manner:

Such an approach is embedded in the rethink from operating and training an integrated air wing to an integratable air wing.

The aircraft itself is modified from the Marine Corp and Air Force versions with an enhanced fuel capacity which required some wing modifications as well to deal with the enhanced weight. The photo below shows off the fuel blister that provides this variant extra range and endurance.

There is another key aspect as well.

The CMV-22 unlike the C-2 can carry an F-35C engine onboard a carrier.

And in 2015, I was onboard the USS Wasp when the Osprey brought an engine onboard the ship to support F-35B operations onboard the ship.

This experiment done in 2015 was obviously successful, and not by chance, the US Navy signed its first contract to launch the CMV-22 program the same year.

And perhaps not by chance, a cutting-edge F-35B pilot is now head of the Osprey program at Pax River.

I Interviewed Colonel Matthew “Squirt” Kelly in his office at Pax River last Fall. In that interview we talked about the state of play for the “Osprey Nation,” and the impact of the broadening set of users of the aircraft.

“There is no other air platform that has the breadth of aircraft laydown across the world than does the V-22.

“And now that breadth is expanding with the inclusion of the carrier fleet and the Japanese.

“We currently have a sustainment system which works but we need to make it better in terms of supporting global operations.

“With the US Navy onboard to operate the Osprey as well, we will see greater momentum to improve the supply chain.”

Then Lt. Col. Kelly after landing onboard the USS Wasp with his F-35B. Credit Photo: Second Line of Defense

And during my visit to Amarillo, a key point about the reach of Osprey Nation and the nature of the community supporting it was driven home to me.

During the visit to the Final Assembly line, Japanese Ospreys were being prepared for delivery to the Japanese military.

In 2015 when the Japanese Ministry of Defence was preparing for the transformation of its defense force to deal with the new challenges in the region, they released a video in which they showed how Japan would enhance its capability to defend its perimeter.

Yet the Japanese had not yet committed to buying Osprey.

And underlying that final assembly line where I saw the Japanese Ospreys being built for delivery was the highly skilled worked force working in that Bell factory.

As one navy speaker noted at the ceremony: “I would like to first acknowledge the artisans that put this fine machine together. I visited the Bell factory on Wednesday and had a brief walk through of this factory yesterday. This is an incredibly complex machine that you have built and I am in awe of your precise talent and even more inspired by the magic that makes it fly.”

By chance, the Mayor of Amarillo, Ginger Nelson, sat next to me at the ceremony and graciously agreed to meet with me later that afternoon at her office.

I asked her directly: “Why Amarillo?”

She answered that we are community committed to excellence and to training workers both responsible to deliver quality and to train those workers.

She noted that the local government and community colleges were working to shape training opportunities for local residents to be able to support the Bell operation as well as the agricultural industry in the area.

“Our values and are commitments to excellence are at the heart of what the Amarillo community is all about,” she said.

Going from the delivery to Japan for its latest aircraft to Amarillo, that is what I would call deterrence in depth.

And for the Chinese government, I would warn you to not mess with Texas.

For an abbreviated version of this article published by Breaking Defense on February 10, 2020, see the following: