By Robbin Laird

In my series focusing on USMC and digital interoperability, the first piece focused on the interaction between platform innovation and integratability.

With the evolution of the capabilities of the new combat platforms generated through Marine Corps aviation, the ability of the Marines to operate in an integrated, air, ground, and sea environment have been enhanced.

To take the next step requires investments in the core platforms to enhance their integratability.

The Marines refer to this as building out digital interoperability and have a plan in place to shape an effective way ahead.

And this way ahead entails both shaping core capabilities to manage networks and the data they can provide as well as to build into existing assets greater capability to participate in the networks most relevant to the operational envelope of particular platforms.

The challenge is a highly interactive one. New platforms shape new opportunities to define new concepts of operations and to shape new combat capabilities. Driving such innovation is crucial which means that new platform introduction will often be disruptive of the existing concepts of operations. New platforms can provide a forcing function dynamic for change.

At the same time, new platforms need to operate with other elements of the combat force, and that tension between platform innovations and inherited concepts of operations is an ongoing dynamic driving change.

What digital interoperability provides is an opportunity to both enhance the capabilities of the existing platforms as well as to share the benefits of what new platforms bring to the combat force.

A key question is posed: How do new platforms interact with and shape integratability challenges, and how digital connectivity can enhance what these new platforms bring to the combat force as well as how can the “legacy” platforms make greater contributions to a combat force being driven by change from new platform introduction?

A clear case in point has been the introduction of the Osprey.

If integration with the legacy force was the key mantra for the USMC, the Osprey would never been introduced. But it was and it introduced range and speed considerations to the insert of the Ground Combat Element which have been historically unprecedented.

If a CH-46 replacement had truly been that disruption would not have occurred, and significant innovation in concepts of operations driven by the disruptive force which the Osprey has provided would not have as well.

The US Army is the lead on a new Future Vertical Lift helicopter which is being designed to have similar reach and range to the Osprey. How this will impact the entire approach to shaping the future US Army is a key strategic question.

But the Marines have already been living in the world of FVL for a decade and a half.

Thinking outside of the helo defined operational box has been a key game changer in thinking about the concepts of operations for the USMC for some time, and adjustments to their concepts of operations have been driven by its operational capabilities.

In order to get full benefit from the Osprey forcing function, the Osprey needed to become a more integratable capability within the MAGTF. Digital interoperability provides a key bridge to do so.

In the next piece I will return to my discussions with Major Salvador Jauregui and Mr. Lowell Schweickart from the USMC Aviation Headquarters who are working on the digital interoperability effort.

And in that piece will focus directly on the question of what DI brings to various platforms in the MAGTF, and how what that brings to those specific platforms can lead to further capability enhancements or changes in concepts of operations.

But here, I want to return to a number of pieces we published in 2014 which highlight how the digital interoperability piece became highlighted as a significant opportunity for Osprey nation.

The speed and range of the Osprey has meant that it can outrun the embarked Marines capability to have the situational awareness they needed when disembarking in the objective area.

How then to solve that problem?

In the following piece published on January 18, 2014, we identified why C2 innovation when coupled with the capabilities of the Osprey created new options for the MAGTF.

With a new system, as innovative as the Osprey, it takes time to shape the course of change.

With its successful use in combat, its ability to work effectively with other elements of the MAGTF, and its core role in shaping innovations such as Special Purpose MAGTF-Crisis Response, the Osprey is becoming a key change agent throughout the MAGTF.

Although the Osprey is a tilt-rotor aircraft, its heart and sole is in supporting the Ground Combat Element (GCE) differently than any airborne capability seen before.

The Marines work the relationship between the GCE and the Air Combat Element (ACE) to shape a capability, which is expeditionary, flexible, and with the Osprey more rapid with greater range for force insertion than before.

But to get to the next phase requires further innovation, this time in terms of how the MAGTF (GCE and ACE) can better use the new emerging capabilities, specifically C3I and fires, to execute its mission more effectively.

The Osprey and KC130J pairing provides an ability to operate at distance and to rethink various missions such as force insertion, extraction of embassy personnel, TRAP and others, to include limited objective MAGTF strike operations.

By not being a relatively slow-moving helicopter that typically requires forward operating bases to conduct long-range operations, the Osprey allows the USMC (and the USAF) to think about how to use the speed and range of the Osprey when paired with organic tanking capabilities to operate fundamentally different from past approaches.

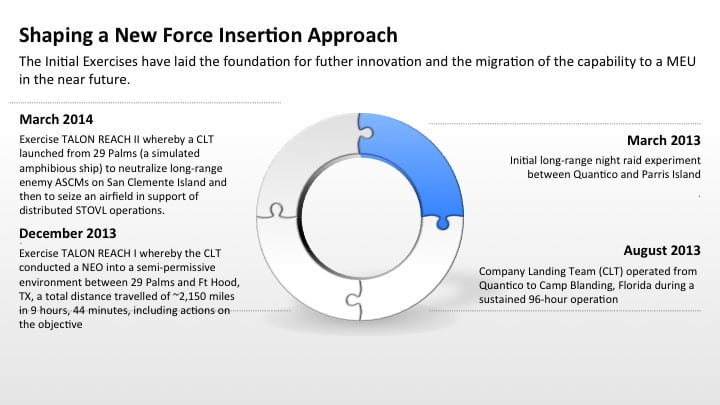

Over the past year, during three separate, long-range, Marine Air-Ground exercises, the Marine Infantry Officer Course (IOC) has worked closely with multiple aviation units to attack this required culture change.

During these experiments, the combined air-ground team has sought different approaches to achieve more effective outcomes, and have used these exercises as means to shape future technological adaptations.

A recent example of this approach was seen in a long-range Non-Combatant Evacuation Operation (NEO) that IOC, serving as a simulated Company Landing Team(CLT), executed into a semi-permissive environment from 29Palms to Fort Hood Texas.

The exercise was called TALON REACH and was the culminating event for IOC Class 1-14. This event was conducted under one period of darkness between 29 Palms California and Ft Hood Texas.

This exercise was made possible by the teaming of the USMC MV-22s and KC-130Js.

During this experiment and those previous, the long-range insertion method proved interesting, but the innovation to drive enhanced capabilities is even more so.

To get a sense of how this innovation process is unfolding, I talked with a participant in the exercise, Lt. Col. Bill Hendricks.

Hendricks is a Cobra driver, and currently is assigned to USMC Aviation Headquarters as the air-ground weapons requirements officer.

A key element of the discussion focused on how mission planning can change significantly with the new configuration of insertion forces and how that approach can, in turn, significantly shorten the time from launch to operating in the objective area. Rather than several hours on the ground planning the mission and then launching the force mission, now the time associated with the Rapid Response Planning Process can be significantly reduced. A new process is being developed.

The insertion force takes off and then does the planning in route (given the range and time in transit) and provides real time information to the GCE and ACE commanders aboard the Osprey prior to going into the objective area.

And this most recent experiment is really only the tip of the iceberg so to speak. Given that the Ospreys are paired with KC-130Js there is no inherent reason that the bigger planes cannot carry mission planning and management support systems.

And as the Harvest Hawk configured C-130s return from Afghanistan, these planes could be used as the lead element in the insertion of a long-range insertion package as well.

Lt. Col. Hendricks started by explaining the role of the CLT within the insertion force.

The CLT is based around highly trained, educated, and equipped infantry Marines, basically pulled out of the regular battalion and they tend to be your more qualified individuals.

The CLT can do raids of duration that are a little bit longer than a standard company could do; but shorter in duration than a battalion could support.

And they could do that because they have the best equipment and they have the best or most highly trained individuals.

The CLT is somewhere on the spectrum between a standard Marine rifle company and a MARSOC unit, as far as the skills that they bring.

It is clear that the CLT requires good ability to have systems for C2, ISR and an ability to work effectively as they move off of the air asset.

The CLT, combined with the MAGTF’s 21st century ACE, provides the nation a unique capability that already is (South Sudan) and will increasingly be in great demand.

To make this happen, the CLT’s current legacy equipment needs to change. The concern is that a lot of their equipment is legacy at best, and very heavy and bulky and not very effective.

And the red force, that they were up against, were outpacing them, as far as their ability to command and control with their own personal IPhones, chat, text messaging, and widely commercially available systems.

These opportunities and concerns bring us back to the focus of Talon Reach. A key focus of the exercise was upon how to close the gap and to give the GCE, in this case the CLT, more effective tools to support force insertion. And to exercise also allows USMC Aviation to better understand the technology, which is most desired and effective for the GCE in their missions operating off of aircraft.

A key shift is from the GCE being primarily voice directed to a combination of voice-directed AND image enabled, combined with a data capability. In the past few years, the GCE receives via voice communication from intelligence officers conclusions about the situation in the objective area determined by data obtained from systems like UAVs.

The approach used in the exercise was significantly different.

Lt. Col. Hendricks :

We had a command center set up in Miramar and via satcom we were sending information updates, via chat messaging that was then received in the back of the airplane on hand-held tablets.

These were all scripted (for it was an exercise) but they would see things like:

“At 1350 zulu time, a crowd is seen gathering in front of the embassy.”

This comes across the net and the four V-22’s that were carrying the infantrymen en route could all see that on the tablet.

We could do the same with regard to imagery as well. We had Harriers out in front of the package that with their lighting pods were taking photos of the objective area where we were doing this insertion and these images were now being sent to the back of the airplanes and distributed as well.

And we had on the airplane full motion video as well. The video was coming from the lightning pod of the Harrier into the back of the lead V-22 with a subsequent re-transmission to the other V-22s.

This allowed as well what one might call the John Madden capability. Referring to John Madden used to call the football games so he had that magic pen that he could circle on the screen. We had the same capability where we could turn it into a still image, circle a certain part of it and then distribute that image amongst the CLT on these hand-held tablets.

You could literally just draw an arrow on the screen, hit send. Just like you would a text message and now everyone has a visual image.

Clearly, this is a work in progress and sorting out the value of still versus full image video is part of the challenge and to get the systems working fully.

Nonetheless, this was the first time that we were able to demonstrate this capability to close to 75 infantry officers to get their feedback.

It is clear that these new capabilities present a great potential for the MAGTF.

This change in equipment will force a re-examination of the current mindset and culture of warfighters accustomed to relying largely on voice-to-voice communications. The addition of imaged enabled communication and data capability will force operators to re-think how current mission profiles are planned and executed.

In the future, infantry squads will be able to plan in flight with regard to what they see and what they think the first approach should be.

Additionally, decision-making will likely be significantly improved as these same units work through what to do while in route to the objective rather than simply receiving intelligence inputs prior to departure.

Lt. Col. Hendricks highlighted the significant impact on time to departure to time on mission.

It is four hours to get there but you are not leaving until you have done up to six hours of planning.

This means that your real response time is ten hours from the time you receive something to actually being on station.

Based on mindset and culture shift, largely based on information and imagery and an enhanced ability to communicate, the future MAGTF could conduct planning en route to the objective area and thus cut response time in support of combatant commander’s requirements in half.

The package, which deployed on this experiment, reflects that the effort is one in progress, moving forward at a rapid rate.

Lt. Col. Hendricks indicated that the six MV-22s included 4 to carry the troops and 2 from VMX-22 to facilitate the innovation in communication and information exchange.

The VMX-22 Ospreys were used to empower the network for the insertion force.

The kind of innovation needed for the next phase is clearly based on continued and effective collaboration between the GCE and the ACE.

According to Lt. Col. Hendricks:

As we go forward with developing these new capabilities we need a collaborative effort between Aviation and the GCE.

They tell us what they need, and we work to provide that to them.

The GCE is going to be a key driver for innovation within the MAGTF being reshaped under the influence of the Osprey and the F-35.

The above article and several accompanying articles which we published in 2014 highlighted the opportunity of combing the forcing function of the Osprey with new approaches to C2 reach to shape a more integratable force which would then have its own tactical and strategic impact.

In my view, this is really the opportunity being opened by the digital interoperability effort.

On the one hand, recognizing that new platforms provide forcing function opportunities.

But on the other hand, working more directly integratability in the C2/ISR domain to both take advantage of the forcing function drivers of change but also providing enhanced capabilities for the new platform by enhanced C2/ISR reach.

Note: In an interview we did with the Major Cuomo, the head of the Infantry Officer Course (IOC) at the time of the 2014 interview, we generated a graphic which highlighted the learning path to doing the Talon Reach effort, an approach which the leaders of the DI effort highlighted as an important on with regard to combat learning and the evolution of specific technologies being woven into the DI thread.

See also, the following:

Talon Reach: Shaping a Combat Cloud to Enable an Insertion Force

Re-shaping Ground Force Insertion: The USMC Leverages Tilt-rotor Technology To Continue to Innovate

USMC Long Range Raid: Shaping an Insertion Force for the 21st Century