By Robbin Laird

To the casual observer, the Super Stallion and the King Stallion look like the same aircraft.

One of the challenges in understanding how different the CH-53K is from the CH-53E is the numbering part.

If it were called CH-55 perhaps one would get the point that these are very different air platforms, with very different capabilities.

What they have in common, by deliberate design, is a similar logistical footprint, so that they could operate similarly off of amphibious ships or other ships in the fleet for that matter.

But the CH-53 is a mechanical aircraft, which most assuredly the CH-55 (aka as the CH-53K) is not.

In blunt terms, the CH-55 (aka as the CH-53K) is faster, carries more kit, can distribute its load to multiple locations without landing, is built as a digital aircraft from the ground up and can leverage its digitality for significant advancements in how it is maintained, how it operates in a task force, how it can be updated, and how it could work with unmanned systems or remotes.

These capabilities taken together create a very different lift platform than is the legacy CH-53E. In a strategic environment where force mobility is informing capabilities across the combat spectrum, it is hard to understate the value of a lift platform, notably one which can talk and operate digitally, in carving out new tactical capabilities with strategic impacts.

The lift side of the equation within a variety of environments can be stated succinctly. The King Stallion will lift 27,000 lbs. external payload, deliver it 110 nm to a high-hot zone, loiter, and return to the ship with fuel to spare. What that means is JLTV’s (22,600-lb.), up-armored HMMWV, and other heavier tactical cargos go to shore by air, rather than by LCAC or other slower sea lift means. For less severe ambient conditions or shorter distances than this primary mission, the 53K can carry up to 36,000 lbs.

With ever increasing lift requirements and advancing threats in the battlefield, there is no other vertical lift aircraft available that meets emerging heavy lift needs. There are a lot of platforms that can blow things up or kill people, but for heavy lift, the CH-53K is the only option.

For the Marines, this is a core enabling capability. The CH-53K is equipped with a triple external hook system, which will be a significant external operations enabler for the Marine Air Ground Task Force. The single, dual and triple external cargo hook capability allows for the transfer of three independent external loads to three separate supported units in three separate landing zones in one single sortie without having to return to a ship or other logistical hub.

The external system can be rapidly reconfigured between dual point, single point loads, and triple hook configurations in order to best support the ground scheme of maneuver.

All three external hooks can be operated independently supporting true distributed operations. For example, three infantry companies widely dispersed across the battlefield can be rapidly resupplied with fuel, ammo, water or other supplies directly at their location—during the same sortie—eliminating the requirement for the helicopter to make multiple trips or for cargo from a helicopter to be transloaded to ground vehicles for redistribution—saving ground vehicle fuel and MAGTF exposure to ground threats.

The CH-53K’s triple external hook system is a new capability for the Marine Corps and an improvement in capability and efficiency over the legacy aircraft it replaces making it a game changer for providing heavy lift in support of combat, humanitarian assistance, and disaster relief operations, notably in a distributed operational space.

The CH-53K design integrates the latest technologies to meet the USMC requirement for triple the lift of the predecessor Super Stallion while still maintaining the size and footprint to remain compatible with today’s ships and strategic air transport platforms.

The aircraft is fully marinized for shipboard operations, including automatic blade fold and design robustness to meet new and extreme requirements for salt-fog and corrosion. It is already certified for transport in C-5 (2 x 53Ks) and C-17 (1 x 53K) aircraft and also includes an integral aerial refueling probe for long range missions or self-deployment.

The work process is very different as well, because of support for palletization. This may sound like logistic geek language, but it is about speed to deliver to the force for its operating efficacy. Given that speed to operation is a key metric for supporting the strategic shift from the land wars to full spectrum crisis management, the CH-55 (aka as the CH-53K) is a key enabler for the new work flow essential to combat success.

The digital piece is a foundational element and why it is probably better thought of as a CH-55. This starts with the fly-by-wire flight controls. The CH-53K is the first and only heavy lift fly-by-wire helicopter.

The CH-53K’s fly-by-wire is a leap in technology from legacy mechanical flight control systems and keeps safety and survivability at the core of the Kilo’s design while providing a portal to an optionally piloted capability and autonomy.

The CH-53K’s fly-by-wire design drastically reduces pilot workload and minimizes exposure to threats or danger, particularly during complex missions or challenging aircraft maneuvers like low light level externals in a degraded visual environment allowing the pilot to manage and lead the mission vice focusing on physically controlling the aircraft.

The fly-by-wire design further complements safety and survivability through physically separated Flight Control Computers, separated cockpit controls with an Active Inceptor System, and load limiting control laws that will extend component lives. Other cargo Helicopters originated in the late 50s/early 60s, predating the emergence of Aircraft Survivability as an engineering discipline.

Not leaving anything to chance, the overall CH-53K survivability process includes an extensive, ongoing Live Fire Test Program, which started at a component level, and culminates with a full-up aircraft test with turning rotors. The CH-53K is the only heavy lift helicopter designed from the ground up to survive in battle, reflecting a 21st century level of survivability.

In addition, the CH-53K was designed from the start in an all-digital environment, taking advantage of virtual reality tools to optimize both manufacture and support of the aircraft throughout its life cycle. Fleet Marine personnel were engaged from the beginning of the design process to ensure the aircraft was designed for supportability and reduced O&S costs–from component access, support equipment, animated work instruction and electronic publications to the system integration with Sikorsky’s fleet management tools that were originally developed to support its commercial S-92 aircraft fleet.

The S-92 has demonstrated greater than 95% availability for a fleet of over 300 aircraft which now boast near 1.5 million flight hours, in harsh North Sea and other off shore Oil & Gas environments. Use of data analytics (“big data”) has proven to save money in the commercial fleet and these same tools are already in place for the CH-53K and being proven on the CH-53E in the interim.

The CH-53K’s triple redundant fly-by-wire design improves maintainability significantly through fault Detection and isolation capability providing the ability to detect failures in actuators and other electrical and electromechanical components including hydraulic leak detection with fault isolation.

While the CH-53K is bigger and far more capable in many important ways, it’s also smaller in terms of its logistics footprint and provides a best O&S value over its entire lifetime. The CH-53K’s logistics footprint is 1/3 less by volume with a 5,000 cubic feet reduction and 1/4 less by weight with a 25, 000 reduction compared to the legacy CH-53E. That’s equivalent to the storage volume of a 2-car garage and the weight of a two up-armored HMMWVs. In the cargo world, that’s 2 standard shipping containers, which is space and available payload on a ship or less equipment to transport to an austere support base.

The design reduces the maintenance workload as well. With no mechanical rigging requirement and fewer moving parts leading to fewer failures, the CH-53K provides a significant reduction in maintenance man hours, a 35% improvement in Mean Time to Repair, and ultimately increased readiness and availability to the warfighter.

Organizational-level maintenance peculiar support equipment for the CH‑53K is based on common and CH-53E support equipment in order to reduce the new peculiar support equipment required for the CH-53K. Only 150 items of peculiar support equipment were developed to support organizational-level maintenance, which is 146 less pieces of support equipment or a 52% footprint reduction compared to the CH-53E. Additionally the CH-53K support equipment was designed to reduce and optimize equipment weight and life cycle cost while material selection and coating changes from legacy aircraft to eliminate use of hazardous materials and provide better environmental protection from corrosion.

The T408-GE-400 engine brings more capability to the CH-53K through 57% more horsepower with a smaller logistics footprint compared to the T64 it replaces in the same size package but with 63% fewer parts. The T408 supports engine on aircraft maintenance and was designed to maximize two levels of maintenance—Organizational to Depot—with all on-wing engine maintenance being performed using the common tools in flight line toolbox further reducing the logistics footprint and maintenance man hours while increasing availability and readiness of the CH-53K.

The CH-53K sets the standard and is the 1st and only true 21st Century Heavy Lift Helicopter.

To be more specific, the current heavy / upper medium lift cargo helicopters that the CH-53K replaces—legacy Chinook, CH-53 A/D/G Sea Stallion, CH-53E Super Stallion and their engines—were literally designed in the mid-20th century.

In the more than half century that has elapsed between the design of these legacy aircraft and the first flight of the CH-53K in 2015, there have been significant advancements in helicopter design and manufacturing.

The CH-53K is superior to its predecessors, not by engineering miracles, but by over a half century of steady engineering and technology progress that was designed and incorporated into the CH-53K from the ground up.

The King Stallion is a totally new helicopter that leapfrogs the CH-53E design to improve operational capability, interoperability, reliability, maintainability, survivability, and cost of ownership.

Finally, the CH-53K is nearing completion of testing and well into production. The program remains on target for a 2021 IOC and 2023 deployment that meets the USMC’s operational needs. The King Stallion is the only aircraft that meets the heavy lift requirements for the USMC, supports the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concept, and provides that safety, survivability, supportability and growth capability to meet the service’s needs for the many decades to come.

A good sense of how the CH-55 (aka as the CH-53K) intersects with the new operating environment was highlighted in interviews I did in both Pax River and Marine Corps Air Station Yuma.

In an interview earlier this summer with a senior MAWTS-1 officer, we discussed the coming of TAGRS and of the CH-53K to the Marine Corps and how these new capabilities would allow for enhanced FARP capabilities and expeditionary basing support.

In that interview with Maj Steve Bancroft, Aviation Ground Support (AGS) Department Head, MAWTS-1, MCAS Yuma, we discussed the way ahead on FARPs enabled by TAGR and CH-53Ks.

Excerpts from that interview follow:

There were a number of takeaways from that conversation which provide an understanding of the Marines are working their way ahead currently with regard to the FARP contribution to distributed operations.

The first takeaway is that when one is referring to a FARP, it is about an ability to provide a node which can refuel and rearm aircraft. But it is more than that. It is about providing capability for crew rest, resupply and repair to some extent.

The second takeaway is that the concept remains the same, but the tools to do the concept are changing. Clearly, one example is the nature of the fuel containers being used. In the land wars, the basic fuel supply was being carried by a fuel truck to the FARP location. Obviously, that is not a solution for Pacific operations.

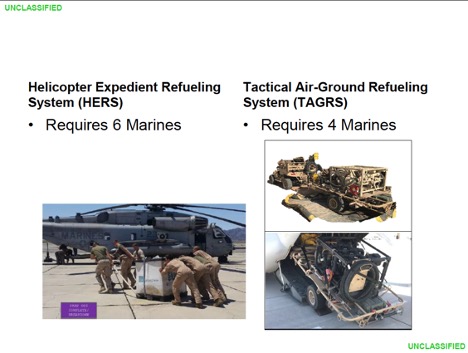

What is being worked now at MAWTS-1 is a much mobile solution set. Currently, they are working with a system whose provenance goes back to the 1950s and is a helicopter expeditionary refueling system or HERS system. This legacy kit limits mobility as it is very heavy and requires the use of several hoses and fuel separators.

Obviously, this solution is too limiting so they are working a new solution set. They are testing a mobile refueling asset called TAGRS or a Tactical Aviation Ground Refueling system.

As one source put it: “The TAGRS and its operators are capable of being air-inserted making the asset expeditionary. It effectively eliminates the complications of embarkation and transportation of gear to the landing zone.”

The third takeaway was that even with a more mobile and agile pumping solution, there remains the basic challenge of the weight of fuel as a commodity. A gallon of gas is about 6.7 pounds and when aggregating enough fuel at a Forward Air Refueling Point or FARP, the challenge is how to get adequate supplies to a FARP for its mission to be successful.

To speed up the process, the Marines are experimenting with more disposable supply containers to provide for enhanced speed of movement among FARPs within an extended battlespace. They have used helos and KC-130Js to drop pallets of fuel as one solution to this problem.

The effort to speed up the creation and withdrawal from FARPs is a task being worked by the Marines at MAWTS-1 as well. In effect, they are working a more disciplined cycle of arrival and departure from FARPs. And the Marines are exercising ways to bring in a FARP support team in a single aircraft to further the logistical footprint and to provide for more rapid engagement and disengagement as well.

The fourth takeaway is that innovative delivery solutions can be worked going forward.

When I met with Col. Perrin at Pax River, we discussed how the CH-53K as a smart aircraft could manage airborne MULES to support resupply to a mobile base. As Col. Perrin noted in our conversation: “The USMC has done many studies of distributed operations and throughout the analyses it is clear that heavy lift is an essential piece of the ability to do such operations.”

And not just any heavy lift – but heavy lift built around a digital architecture.

Clearly, the CH-53E being more than 30 years old is not built in such a manner; but the CH-53K is. What this means is that the CH-53K “can operate and fight on the digital battlefield.”

And because the flight crew are enabled by the digital systems onboard, they can focus on the mission rather than focusing primarily on the mechanics of flying the aircraft. This will be crucial as the Marines shift to using unmanned systems more broadly than they do now. For example, it is clearly a conceivable future that CH-53Ks would be flying a heavy lift operation with unmanned “mules” accompanying them. Such manned-unmanned teaming requires a lot of digital capability and bandwidth, a capability built into the CH-53K.

If one envisages the operational environment in distributed terms, this means that various types of sea bases, ranging from large deck carriers to various types of Maritime Sealift Command ships, along with expeditionary bases, or FARPs or FOBS, will need to be connected into a combined combat force.

To establish expeditionary bases, it is crucial to be able to set them up, operate and to leave such a base rapidly or in an expeditionary manner (sorry for the pun). This will be virtually impossible to do without heavy lift, and vertical heavy lift, specifically.

Put in other terms, the new strategic environment requires new operating concepts; and in those operating concepts, the CH-53K provides significant requisite capabilities. So why not the possibility of the CH-53K flying in with a couple of MULES which carried fuel containers; or perhaps building a vehicle which could come off of the cargo area of the CH-53K and move on the operational area and be linked up with TAGRS?

As this potential development highlights, if we called it a CH-55, we would grasp which the coming of the CH-53K has a significant impact on the way ahead for mobile expeditionary basing, which is itself a key building block in the way ahead for the integrated distributed force. Or put another way, multiple basig is a key capability required for operations in the extended but contested battlespace; and the CH-55 can provide a significant capability to enable multiple basing,

The featured photo is credited to NAVAIR.