By Robbin Laird

The Marines like the other services in the U.S. military have been focusing on how to distribute their forces for both their core missions and in support of joint and coalition operations.

Force distribution has been necessitated by the growth of precision strike available to both peer competitors and non-state groups or small states which can act by leveraging elements of such capability when the Marines carry out a core mission as a 911 force.

What the Houthi’s demonstrated in the Red Sea affects the use of force by the United States in acting in a crisis affects force building calculations as well as operating against a peer competitor.

And never forget that war in Vietnam: a non-peer competitor can access with the add of a peer competitor their weapons. So don’t just focus on core capabilities of the peer competitor without forgetting the reality of weapons transfer.

As the nation’s 911 force, the Marines need to be ready to deliver an integrated force to a crisis point to be able to insert force. This is after all, why the Marines have a unique integrated air capability to work with its Ground Combat Element and able to operate without a capital ship. This is why they have modern fast jets as a key element of how they insert force. The U.S. Army does not have fast jets; the USMC does. This means that the Marines can respond to a crisis rapidly with a coherent integrated force capability.

But to do so in evolving combat conditions means that they have to build in some of the skill sets essential for force distribution, such as having effective local area C2 and ISR baked into the force, and to lower signature management.

This 911 capability inherently requires a mobile agile force capability whether coming from land or sea. Often a 911 intervention in fact relies on mobile basing skills.

In other words, force distribution skill sets are drawn upon even when delivering a larger integrated USMC force or a MAGTF to a crisis management event.

Under Commandant Berger, the Marines began to emphasize the need to build skill sets which allowed the Marines to work in a certain way with the joint force, prioritizing their maritime role, and doing so in terms of being able to project power into the weapons engagement zone of the enemy and to operate as an inside force.

But of course, one could operate as an inside force in terms of Marines or working with the joint force or the coalition force.

For example, when looking at how the Marines can operate in the Nordics, the Marines can work on how to embed themselves in the Nordic region whereby the Nordics are the “inside force” to use the language of the USMC force design effort.

What the Marines are doing, in effect, is taking their long history of working mobile basing, and developing new tools and new approaches to shaping a way ahead to build more agile, and dispersed elements of delivering a mobile basing capability. And to do so, they are evolving the ecosystem to leverage their operation from sea bases and using their integrated air capability to do so.

But such a tool set needs to operate for a tactical purpose within an overall strategic scheme. It is a means to an end; it is not an end in itself.

In other words, the Marine Corps effort to be able to operate in terms of an EABO or Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations needs to be part of a larger tactical whole in terms of either a USMC force insertion or of a joint force or of a coalition force. And to do so, the Marines are shaping their ecosystem for force distribution to be able to do so.

EABOs are extensively exercised by the Marines. For example at MAWTS-1, the premier training center for the Marines, EABOs are a central piece of the capability being developed by the Marines in shaping their force development.

For example, in an interview I did at MAWTS-1 with the then CO of MAWTS-1, Col Purcell, he highlighted the focus on EABOs but cautioned that this was a tool within an approach not an end in itself.

Col Purcell talked about the changes that have occurred since taking command. He underscored that one major change has been working in maritime strike packages into the force as well as enabling the ability to do EABOs or Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations.

But he made it clear that EABOs are not an end of themselves: what combat purpose do they meet and how do they make for a more effective force in particular missions?

This is how he put it: “The ability to conduct expeditionary advanced bases, that’s a capability that’s going to enable something else. It is not a mission of itself. EABOs are what we do in an operational area to project lethality and to project our power and delivering capability to deter an enemy. It has to be about the ability to integrate all six functions of marine aviation in support of a larger mission.”

The Marines have worked Forward Arming Refueling Points for some time and are now transitioning those skills into EABO capabilities. In other words. the Marines have been working new ways to do FARPs as a way to do EABOs, but there are key limitations to what one can do in the real world.

- And ultimately, the key combat question can be put simply: What combat effect can you create with an EABO?

- How does the joint force use an EABO in creating a joint effect?

- And what is the relationship of the creation of EABOs to what the Marines do when the National Command Authority calls on them to deploy?

This can be put another way as well. In 2022, I published a report on the Marines and mobile basing and in that report I highlighted an interview with an especially insightful Marine Corps leader which focused on the key question: what is the mobile base for and for how long is it need to play the designated tactical role within a strategic context?

In a 2020 interview with then Maj Steve Bancroft, Aviation Ground Support (AGS) Department Head, MAWTS-1, he highlighted a key aspect of force distribution:

In this discussion it was very clear that the rethinking of how to do FARPs was part of a much broader shift in in combat architecture designed to enable the USMC to contribute more effectively to blue water expeditionary operations.

The focus is not just on establishing FARPs, but to do them more rapidly, and to move them around the chess board of a blue water expeditionary space more rapidly. FARPs become not simply mobile assets, but chess pieces on a dynamic air-sea-ground expeditionary battlespace in the maritime environment.

Given this shift, Major Bancroft made the case that the AGS capability should become the seventh key function of USMC Aviation.

Currently, the six key functions of USMC Aviation are: offensive air support, anti-air warfare, assault support, air reconnaissance, electronic warfare, and control of aircraft and missiles. Bancroft argued that the Marine Corps capability to provide for expeditionary basing was a core competence which the Marines brought to the joint force and that its value was going up as the other services recognized the importance of basing flexibility,

But even though a key contribution, AGS was still too much of a pick-up effort. AGS consists of 78 MOSs or Military Operational Specialties which means that when these Marines come to MAWTS-1 for a WTI, that they come together to work how to deliver the FARP capability.

As Major Bancroft highlighted: The Marine Wing Support Squadron is the broadest unit in the Marine Corps. When the students come to WTI, they will know a portion of aviation ground support, so the vast majority are coming and learning brand new skill sets, which they did not know that the Marine Corps has. They come to learn new functions and new skill sets.

His point was rather clear: if the Marines are going to emphasize mobile and expeditionary basing, and to do so in new ways, it would be important to change this approach. Major Bancroft added: I think aviation ground support, specifically FARP-ing, is one of the most unique functions the Marine Corps can provide to the broader military.

He underscored how he thought this skill set was becoming more important as well. With regard to expeditionary basing, we need to have speed, accuracy and professionalism to deliver the kind of basing in support for the Naval task force afloat or ashore.

With the USMC developing the combat architecture for expeditionary base operations, distributed maritime operations, littoral operations in a contested environment and distributed takeoff-vertical landing operations, reworking how to execute FARP operations is a key aspect. FARPs in the evolving combat architecture need to be rapidly deployable, highly mobile, maintain a small footprint and emit at a low signature.

While being able to operate independently they need to be capable of responding to dynamic tasking within a naval campaign. They need to be configured and operate within an integrated distributed force which means that the C2 side of all of this is a major challenge to ensure it can operate in a low signature environment but reach back to capabilities which the FARP can support and be enabled by.

This means that one is shaping a spectrum of FARP capability as well, ranging from light to medium to heavy in terms of capability to support and be supported. At the low end or light end of the scale one would create an air point, which is an expeditionary base expected to operate for up to 72 hours at that air point. If the decision is made to keep that FARP there longer, an augmentation force would be provided and that would then become an air site.

Underlying the entire capability to provide for a FARP clearly is airlift, which means that the Ospreys, the Venoms, the CH-53s and the KC130Js provide a key thread through delivering FARPs to enable expeditionary basing.

This is why the question of airlift becomes a key one for the new combat architecture as well. And as well, reimagining how to use the amphibious fleet as lilly pads in blue water operations is a key part of this effort as well.

Then during my 2023 visit to MAWTS-1, I discussed the evolution of the USMC approach with Col Purcell as follows:

As the Marines operate Ospreys. F-35s and now CH-53Ks, the Marines are bringing significantly capability to the evolving mobile basing function.

Mobile basing is playing a central role in the current phase of USMC transformation.

Col Purcell put it succinctly: “We are taking capability which we have had for some time, but focused on how we can move more rapidly from mobile base to mobile base. We have to find ways to make mobile bases, smaller, more distributed and persist for shorter periods of time”.

Another key aspect is that what has been a core competence of the USMC now is becoming a key capability for the wider joint and coalition force.

Col Purcell put it this way:”I think the challenge for all the forces, whether it’s the Air Force, the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, or the coalition forces is that the sustainment of distributed forces is challenging. How do we adapt our maintenance, logistical and sustainment systems that have been used to operating from austere bases, but now enhance the mobility of those austere bases?”

The type model and series of USMC aircraft are embedded in the USMC thinking about mobile basing.

But as Purcell put it: “We have to find ways to make mobile bases, smaller, more distributed and persist for shorter periods of time”.

What is necessary to be able do so, and how to do it, is a key focus of the way ahead.

This means adapting effectively to the payload revolution and the ability to deliver maritime effects via use of autonomous systems working with the manned force. Rather than thinking in terms of manned-unmanned teaming, the reality is creating a capability to deliver combined arms effects or alternatively combined effects. Or it might be put this way: With the integrated distributed force, the Marines are leveraging their core assets configured differently with the addition of new technology — including autonomous systems — enabling further evolution of the desired concept of operations approach,

In short, as I argued in a discussion with LtGen (Retired) Heckl in an interview with him earlier this year:

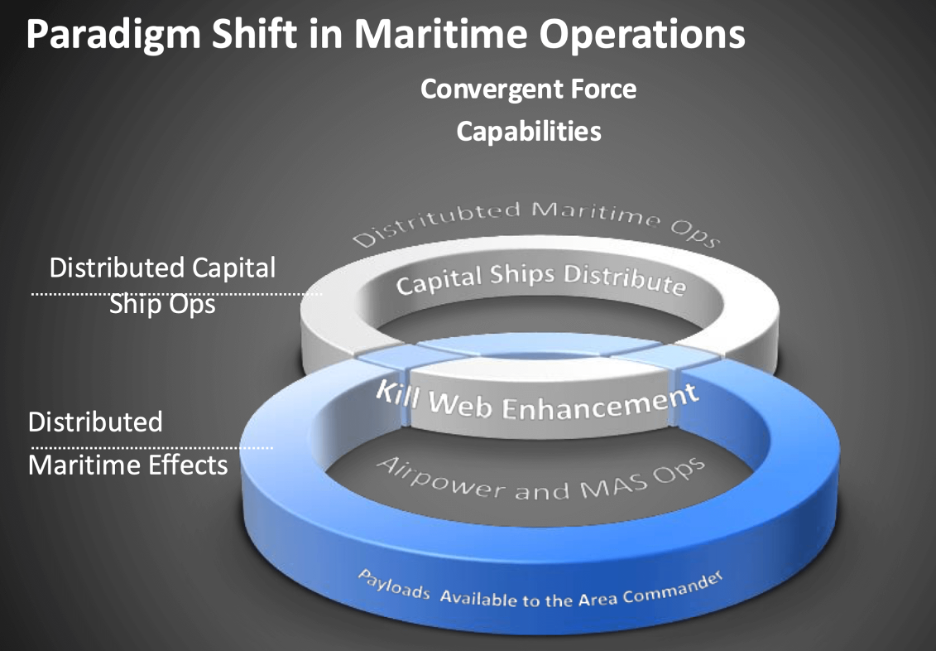

“Clearly Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) understood in terms of distributing capital ships is very important in shaping an effective way ahead, but DMO understood in terms of delivering distributed maritime effects is clearly of growing importance given technological developments and given the shortfall in legacy shipbuilding approaches.

“DMO in terms of delivering distributed maritime effects is where EABO is best understood. In shaping a way ahead for EABO the air platforms available to the USMC coupled with innovations in autonomous or manned maritime platforms create a clear path to shift from the legacy ship building approach.

“In a DMO effects approach one is focused on combat clusters whereby each asset is interactive with other members of the combat cluster and will NOT have the full gamut of capabilities which a maritime task force member would have in terms of organic defensive and offensive capabilities.”

In my view, what the Marines are shaping are capabilities that can contribute both to empowering DMO but shaping a wide range of innovative ways to deliver distributed maritime effects as well — with the same technology but configured to specific mission sets.

A local area commander will need to master both in shaping an effective combat approach dealing with an adversary, whether peer or local group tapping peer competitor capability.

And the Marines uniquely are shaping their force going forward in both approaches.

Note: All quotes are taken from our recent MAWTS-1 book.