By Robbin Laird

I am crafting a series on mobile basing as a strategic capability for the joint force.

The strategic importance of mobile basing goes up with the importance of complicating your adversaries’ targeting solutions and force projection targets.

Seabasing is clearly a key part of being able to do mobile basing, but with the shift from a classic understanding of amphibious operations to enhancing the expeditionary capabilities of the joint and coalition force, what kind of seabases might be crafted in the years ahead?

In this part of the series, I will address re-imaging how to use the extant amphibious force very differently for missions like sea control and sea denial.

There is no area where better value could be leveraged than making dramatically better use of the amphibious fleet for extended battlespace operations.

This requires a re-imaging of what that fleet can deliver to sea control and sea denial as well as Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC) offense and defense.

In the midst of the land wars, the USMC leadership understood that they needed to prepare for the return to the sea as a primary domain for the way ahead for USMC combat operations. It is difficult to overstate how dominant the warfighting experience ashore has been for shaping this generation of Marines.

But it is also an overstatement that the return to the sea started with call of the current Commandant to enhance naval integration capabilities for the USMC itself.

That call to return to the sea was crystallized in the launching of the Bold Alligator series of exercises beginning with Bold Alligator 2011.

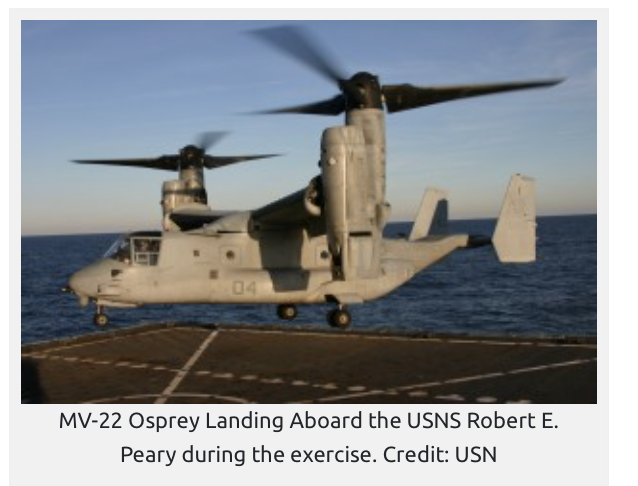

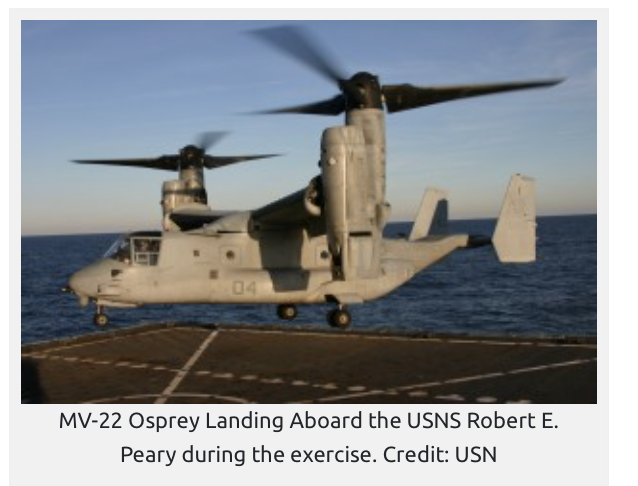

We attended several of the Bold Alligator series exercises and witnessed how the USMC, the U.S. Navy and a number of allies and partners joined in the relaunch in many ways of the next generation of amphibious warfare. For that relaunch was happening, as the Osprey was joining the fleet.

Bold Alligator 2012 (BA-12) was a training exercise for the expeditionary strike group, and the shaping of a new template for the amphibious task force with the coming of the Osprey and the anticipated arrival of the F-35. The template introduced in BA-12 provided a lay down within which force modernization associated with the F-35B and the VM-22 unfolded.

What was evident in that exercise, and the Bold Alligator exercises which followed, was that the amphibious fleet was shifting from using the ships to function largely as a Greyhound bus carrying Marines ashore to becoming a strike force at sea, and from the sea. At that 2012 exercise we discussed the effort being generated at the time to lay down a new template with officers involved with that exercise

Capt. Sam Howard at the time of the exercise was Special Assistant to the Chief of Staff of U.S. Fleet Forces Command in Norfolk VA. Marine Col. Phil Ridderhof, senior Marine Corps adviser to U.S. Fleet Forces Command in Norfolk, Va. Capt. Howard began his career in destroyer operations and most recently before his Norfolk Assignment was the skipper of the USS Bataan. During his time on Bataan, he participated in the Haiti relief efforts.

Capt. Howard emphasized that one of the opportunities generated by the exercise was to familiarize other services with the key advantages provided to the joint force by seabasing. “A seabase is a concept that regrettably is foreign to the other services, at least in real practice; and we were able to certainly demonstrate it in real practice in real-time in the case of Haiti and will be able to expand on the exercise.” Howard underscored the importance of the exercise as a combined arms approach and useful to re-shaping military doctrine. “It’s a combined arms endeavor, and so getting to that thought process of making it a combined arms thing is certainly very important to us.”

Col. Ridderhof picked up on the combined arms theme introduced and discussed by Capt. Howard. He emphasized that the exercise was built in part around operating at a different level than an Amphibious Ready Group-Marine Expeditionary Unit (ARG-MEU) was capable of operating. “The ARG and the MEU are very important, very capable. When you start getting bigger than the ARG and the MEU an amphibious operation is not simply a quantitative increase. There’s a qualitative difference in how you think about organizing the task force.

“The ARG-MEU is built around three core ships and the MEU is of a regimental size, with a battalion landing team, combat logistics, battalion, and the composite squadron. The MEB being used in this exercise is a different animal. One of our challenges in the Marine Corp is how do you describe the MEB? It can be anywhere from 10,000 to 17,000 soldiers, but in general, it is a regimental landing team with at least three battalions, plus a Marine air group size of an aviation combat element and combat logistics regiment-sized support element.

“One of the key things is that to do all six functions of Marine Corp Aviation, to do command and control, is central to the operational capabilities. A MEU has little pieces, but to do the big Marine Corp Aviation Command and Control pieces is a significant jump in capability. You need all of the pieces of Marine aviation, and then all the logistics to sustain that for 30 days plus.”[1]

And the large-deck carrier is shifting its approach as part of this operational construct. Col. Ridderhof underscored: “Bold Alligator is testing today’s capability but because we haven’t done this this way, the Combined Force Maritime Component Commander (CFMCC) has typically not been considering the littoral as a whole, going all the way to that objective ashore as his battle space. He’s influencing it surely but hasn’t been thinking of it all the way there. Just as the ARG MEU would be first on the scene, how does the Carrier Strike group fold into the scalability of the operation?”

Capt. Howard emphasized: “The reality is, all this is in the context of a joint war fighting organization. And among the lessons we will take from this is how to develop further the unique war fighting relationship between Navy and Marine Corp and how does that best plug into the total force, joint force.”

Obviously, the refocus on the strategic shift from the primacy of the land wars to engaging peer competitors was already underway in this Bold Alligator 2012 exercise. In our interview with Brig. Gen. Owens, the 2nd MEF Commander, held after that exercise, he highlighted how he saw the exercise effort. “One of the things that was different in this exercise from many previous amphibious large-scale exercises is we executed in what we called a medium threat, anti-access, area denial (A2AD) environment. The threat focus is primarily on the area denial piece, which is closer in, but which is more realistic for the timeframe of the exercise.

“The threat we faced at sea started with submarines, missile patrol boats, fast-attack craft, fast inshore attack craft, and some asymmetric threats with commandeered fishing boats, low slow-flyers, and some tactical air. But of greater concern was coastal defense cruise missiles, initially fixed sites, as well as mobile, and then ultimately, just a threat of additional mobile sites.

“And then, the most ubiquitous threat that we’re going to face is mines. In the exercise, we faced a very robust mine capability. We had a wide range of capabilities on the Navy side to help deal with those threats, but we also integrated the MEB in that, particularly our air. These assets were used both in targeting threats to the amphibious task force ashore, as well as providing defense of the amphibious task force primarily with our aviation asset. But we also involved some of our ground combat elements when they were aboard the ship.

“That continued even after we went ashore. And this is something that we really haven’t practiced; this full integration, of the Marine capability in the overall ability to both to project force, and to protect those naval assets that are projecting that force.”

The exercise was focused on redesign of the current force structure to achieve the desired combat effect in order to lay down a template for the changes to come. As Brig. Gen Owens put it: “I think flexibility is a key word. In this exercise, we focused on today’s forces for today’s fight. What it really was about was getting the greatest impact, the greatest benefit out of the capabilities we have. For example, in our countermine effort, we recognize that in order to do countermine work here on the east coast of the U.S., it’s going to involve coalition participation. So, we had Canadian mine hunters out working with U.S. divers in conjunction with Dutch divers, Canadian divers supported by the Coast Guard providing a cutter to help provide force protection for the mine hunters.

“And our Navy forces provided close in protection for both the mine hunters, and then subsequently, for some of our maritime sealift command shipping that was coming into the same areas. Thus, in addition to integrating the Marine and Navy pieces, we also expanded our search to what other capabilities that other countries, other services, for instance, the coast guard, and even the interagency could provide. We didn’t really touch on the inter-agency aspect too much in Bold Alligator 12, but it is an aspiration for the future. We want to be able to tap into capabilities that will help us defeat some of these asymmetric threats, in particular, in order to project force ashore.”

Brig. Gen Owens underscored a very key point about shaping a way ahead with the force you have to shaping the future force. “From this point of view, the goal of the exercise was to shape an effective concept of operations with current capabilities. We’ve got to have the concept of operations in place as we integrate new capabilities going forward.”

The latest capability which was included at the time was the Osprey. In fact, while journalists waited on shore for the insertion force, the Osprey team had led an assault deep into the battlespace. And even more interestingly, the Ospreys launched from a range of seabases, including a Military Sealift Command ship. At the time, we highlighted how the coming of the Osprey impacted thinking about the amphibious assault force. “An assault raid was conducted from the seabase deep inland (180 miles) aboard the Ospreys with allied forces observing or participating. The Osprey was the key element operating in this exercise, which was not there during the last big “amphibious” exercise. [2]

And with the launch from an MSC ship, the Osprey was highlighting the next phase, rather than focusing on the ARG-MEU, one could think in terms of an amphibious task force.

This is how Brig. Gen Owens highlighted the importance of the event. “The T-AKE is bringing in our dry cargo. So they bring in beyond what the amphibious ships carry, they’ll bring in food, water, and they are ships that bring in our ammunition. That was what we exercised using the V22s to land on the T-AKE, and we had our logistics regiment Marines posted aboard the TAKE to work on the distribution piece.”

In fact, the “return to the sea” energized by the training efforts in the Bold Alligator exercises came at the same time that the Osprey was making its broader impact on the USMC. There is no more dramatic case of a platform introducing disruptive change in a service than the Osprey to the USMC.

The USMC is the only tiltrotor-enabled combat force in the world, and it has introduced significant change throughout the redesign of the USMC and is continuing to do so as the USMC works its evolving approach to integration with the U.S. Navy in blue water expeditionary operations.

After an initial learning curve of how to integrate the Osprey with the Amphibious Ready Group-Marine Expeditionary Force, the speed and range of the Osprey changed the ARG-MEU and reshaped how the amphibious ships would deploy in support of combatant commanders.[3]

In Bold Alligator 2013, the working relationships between the U.S. Navy and the USMC were strengthened as the U.S. Navy began to focus more on how to support sea-based power projection with USMC force mix.

As Col. Bradley Weisz, Deputy Commander, Expeditionary Strike Group TWO, commented at the time about Bold Alligator 2013: “We are getting away from the legacy stove-pipe systems and moving to better collaboration, more integration with our entire fleet force. This is absolutely essential in today’s complex and constantly evolving operating environment; especially when you start talking about the increased anti-access and area-denial (A2/AD) threats that we will face and encounter in the littoral regions. Yes, we are developing and shaping some innovative approaches to deal with these emerging threats.

“As far as leveraging our sea basing capabilities in direct support of our amphibious forces, we will aggressively employ and utilize nine military sealift command ships, MSC ships, as part of our logistics task force. We will have three fleet oilers (T-AOs) that can hold and carry a sizable amount of class I (subsistence) and class III (POL). We will also have two highly capable dry cargo/ammunition ships (T-AKEs) that can haul and deliver substantial amounts of class III (POL) and class V (ground/aviation ammunition) products.

“Along with the T-AOs and T-AKEs, we will have one fast combat support ship (T-AOE) that can provide significant class I (subsistence), class III (POL) and class V (ground/aviation ammunition) capabilities in support of our CSG and ATF forces. Additionally, we will employ and utilize one Aviation Logistics Support Ship (T-AVB) that will provide crucial aviation intermediate maintenance support and repair services to all of our landing force aircraft afloat. This includes all fixed wing, rotary wing, and tilt rotor aircraft afloat.”

Bold Alligator 2014 was a crisis response exercise and continued the work of Bold Alligator 2012 and Bold Alligator 2013. The exercise involved working with an evolving C2 capability to manage forces operating throughout key objective areas. The presence of the Osprey allowed the U.S. and its allies to operate against longer range objective areas as well as other objective areas reachable by rotorcraft and reinforced by landing forces.

The seabases involved in the exercises were characterized by logistical integrity meaning the insertion forces can be supported by the seabase, and it is not necessary to build forward operating bases or to land significant supplies ashore in order to prosecute missions. It is a force tailored to crisis management, as opposed to having to rely on bringing significant forces ashore along with their gear in order to mount operations.

A key part of the Bold Alligator 2014 exercise was a major effort to rework command and control for force insertion from the seabase able to work with the maneuver forces ashore.

Follow up interviews in 2015 with Maj. Gen. Richard L. Simcock II, Commanding General, 2d MEB, and Maj. Marcus Mainz, lead 2d MEB planner for Exercise Bold Alligator 2014 highlighted the evolving approach. They underscored those innovations in aviation allowed the Marines to extend their reach and provide greater flexibility for amphibious operations. The reworking of the amphibious fleet to deliver capabilities to project power from the sea and the ability of the infantry to implement innovations in maneuver warfare and force insertion require creativity in operational design and C2.

2d MEB exercises C2 of scalable and modular forces by delegating it to a level where tactical operations are more effective. This construct facilitates mastery of the operational environment in a fluid combat situation by keeping focus at the appropriate levels. It gives the MEB CE (command element) the capability to focus on the operational art that bridges the strategic and tactical levels for political objectives.

Execution of the mission, empowerment of subordinate leaders at the appropriate level, and maintaining situational awareness of the overall situation is a key challenge for C2. The complexity begins with incorporation of joint and coalition forces for Combined Joint Task Force (CJTF), operations.

Given that joint and coalition capabilities enhance response time and effectiveness of global operations, C2 takes on a whole new meaning when shaping the appropriate composite force for missions across the ROMO (Range of Military Operations), which makes it central to effective Marine Corps Operations.

Maj. Gen. Simcock explained in his interview that the importance of “providing the Combatant Commander with a force capable of plugging into various joint, coalition, and interagency requirements is essential. The realities of the 21st century security environment demand a smart power approach inclusive of all services of the military, our partners and interagency organizations, which play an integral role in fulfilling National Security Strategy.”

Integration of allied and partner nation operational capabilities and systems with the U.S. amphibious fleet will develop, in effect, a global U.S.-Allied amphibious fleet capability. Maj. Gen Simcock also discussed emerging demand for partnership with 2d MEB in global security “since the Marine Corps has revitalized the MEB concept capable of world-wide deployment, we have been contacted by many of our coalition partners, allies and other nations interested in training and operating with 2d MEB.”

The way Maj. Mainz explained it: “Composite forces are created when you take disparate forces, which are underneath different command and control structures, and place them underneath one commander tasked with a specific mission. The 2d Marine Expeditionary Brigade is ‘a receiver of forces.’ We work various compositing options and shape the C2 for those forces coming together to perform the mission.”

Maj. Mainz likened the 2d MEB Command Element (CE) to a Swiss army knife.

“We want to be the Swiss Army knife of command and control. We want to morph or adapt into whatever environment we’re in—coalition or joint. 2d MEB sees itself as a scalable CE capable of C2 for disparate forces, coalition and/or joint, to address the unique requirements of Combatant Commanders in uncertain environment.

“The unique term we used during Bold Alligator is we can become a Commander of MAGTFs, not a MAGTF Commander. What that means is we see our Command Element as so flexible we don’t have to go into a normal Marine construct.”

I will stop with Bold Alligator 2014, but the key point is that prior to significant withdrawals from the Middle East engagement, USMC leaders focused on the return to the sea and reworking with the Navy, how to deliver an integrated force from the seabase to project force ashore and to support it afloat.

[1] The six functions of Marine Corps Aviation are offensive air support, anti-air warfare, assault support, air reconnaissance, electronic warfare, and control of aircraft and missiles.

[2] Robbin Laird, “Bold Alligator: A Glimpse of Marine, Navy Future,” Breaking Defense (March 21, 2012), https://breakingdefense.com/2012/03/bold-alligator-a-glimpse-of-marine-navy-future/

[3] Robbin Laird and Murielle Delaporte, The Osprey and Disruptive Change: The Operational Impact of the Osprey on the USMC, draft manuscript in progress.

Featured Photo: A CH-53E Super Stallion takes off from Fort Pickett, Va., to return to the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima (LHD 7), during an amphibious assault exercise as part of Bold Alligator 2012.

Exercise Bold Alligator 2012, the largest naval amphibious exercise in the past 10 years, represents the Navy and Marine Corps’ revitalization of the full range of amphibious operations. The exercise focuses on today’s fight with today’s forces, while showcasing the advantages of seabasing.

FORT PICKETT, VA.

02.07.2012

Photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Christopher Lenart

Expeditionary Combat Camera

Brigadier General Owens on Lessons Learned in Bold Alligator 2012 from SldInfo.com on Vimeo.