Video made to celebrate the 35th Anniversary of the Air Force Special Operations Command on May 22, 2025.

HILL AFB, UTAH

05.19.2025

Video by Staff Sgt. Tristan Biese and Airman 1st Class Jamie Echols

2D Audiovisual Squadron

Video made to celebrate the 35th Anniversary of the Air Force Special Operations Command on May 22, 2025.

HILL AFB, UTAH

05.19.2025

Video by Staff Sgt. Tristan Biese and Airman 1st Class Jamie Echols

2D Audiovisual Squadron

By Pierre Tran

Le Bourget, France – A long-simmering dispute between Airbus and Dassault Aviation on the share of high-value work on a planned European fighter jet boiled over at the 2025 Paris air show, which opened June 16 with a summer heatwave warming the tarmac.

The June 21 U.S. strike with bunker busting bombs of three nuclear related targets in Iran underscored the significance of the military aircraft and weapons displayed at the 55th edition of the air show, held in the northern suburbs of the capital.

An aerobatic display of a Dassault Rafale fighter jet in the red, white, and blue of the French flag opened the show, reflecting national pride in the aerospace sector. The show organizer, Gifas, told a June 5 press conference the U.S. was the second-largest national exhibitor after France at the showcase for aeronautics and space technology.

Beneath the glitter of the show, which closed June 22, industry executives bore in mind the loss of more than 240 lives in the June 12 crash of a Boeing 787 Dreamliner flown by Air India. In the military world, there was Israel’s extended air and missile attack on Iran, pointing up Israeli dominance of the Iranian skies, while Teheran fired ballistic missiles in retaliation.

In other theaters of conflict, India has yet to give a detailed account in response to Pakistan’s claim of downing the Rafale in combat, while Dassault has said what counted was accomplishing the mission, not the aircraft.

Dassault executive chairman Eric Trappier told June 17 Bloomberg TV that Airbus posed governance problems on the European fighter project.

Airbus Defence and Space, based in Germany, is the industrial partner of Dassault, the French prime contractor, on the new generation fighter (NGF) at the heart of the ambitious European future combat air system (FCAS).

“We may go it alone,” Trappier said at the show, with the mercury rising on troubled corporate ties.

If there was good cooperation, then it made sense to stay in the partnership on the fighter, he said, but added that he was “not happy with the governing system.”

The governance rules on FCAS meant Dassault sat at the table negotiating with the German and Spanish Airbus units, with the latter two entitled to two thirds of the work share, he said. The work share reflected the three nations backing the project rather than the companies’ technological skills.

France, Germany, and Spain were financing the project, with Belgium keen to enter the deal.

It could be argued that rising costs and the call for shareholders’ return have made it harder for manufacturers to go it alone. That raises the need for government funding, making it a political decision rather than purely corporate on whether to pull out.

A senior Airbus executive, Jean-Brice Dumont, told reporters June 17 Dassault was clearly the prime, adding there was also a claim for a work for based on the equal share of the three nations backing FCAS.

“What we don’t challenge is that there is an appointed leader for the fighter program,” he said. “That leader is named Dassault Aviation.

Dumont, head of air power at Airbus Defence and Space, spoke calmly, perhaps attempting to pour oil over troubled waters.

“Dassault has the lead of the so-called pillar one – NGWS (new generation weapon system).

There has to be an even share corresponding to the share of our governments. That doesn’t have to become toxic in the programme,” he said.

“We have to aim for something that is simple enough. Cooperation meant there would be interdependency, which had to be ‘healthy,’” he said, pointing up the need for government support to advance the FCAS project.

Airbus was not planning to move to the global combat air programme (GCAP) and leave FCAS, he said.

Airbus DS is a unit of Airbus, an airliner builder based in Toulouse, southern France.

Dumont previously worked in the Direction Générale de l’Armement procurement office on the Franco-German Tiger attack helicopter before moving on to work on the NH90 military transport helicopter at Eurocopter, renamed Airbus Helicopters.

Jean-Pierre Maulny, deputy director of the Institut des Relations Internationales et Stratégiques, a think tank, told June 11 the Anglo-American Press Association that European allies needed to share technology, to pursue a “strategic solidarity. This was in preference to the “best athlete” approach.

The DGA backed the latter, which secured a leading position for Dassault in building fighters. France has the “competence,” while Germany has the money, he said.

“It’s very difficult,” he said.

France is in financial dire straits, with a 2024 public sector budget deficit of 5.8 pct, up from 5.4 pct in the previous year, national statistics agency INSEE has said. That calls for big government spending cuts to meet a European Union target of 3 pct by 2029.

Meanwhile, there was a perceived need for European allies to replace key U.S. capabilities – known as “enablers — as Washington was seen as withdrawing from the European theatre.

Europe has a problem with “enablers,” he said, referring to the lack of European built satellites, deep-strike weapons, defense against air and missile attacks, spy planes, intelligence gathering, air-to-air refueling, and strategic air transport.

The 27 E.U. member states, and the U.K. and Norway had much to do, and should act collectively, he said. European allies had five to 10 years to build up the defence industrial and technology base in Europe.

Dassault has a history of building its own aircraft and delivering the flight control technology, said Sash Tusa, analyst at Agency Partners, an equities research house.

If there is cooperation, there will be technology flying for 40-50 years, paid for by the partner governments, he said. Alternatively, Dassault has work in the pipeline for the F5 and eventual F6 of the Rafale and a planned unmanned combat air vehicle based on the Neuron demonstrator.

Meanwhile, Germany clearly has a nearer-term priority to fund, and bring into service, the F-35, he said.

An industry source said Dassault was working on F5, and there was nothing planned for an F6 version.

FCAS appears to be lagging further behind the global combat air program, which seems to be on its third design iteration, Tusa said.

Italy, Japan, and the U.K. are the three nations backing GCAP, based on the Tempest, a British-led fighter project. The aim is to fly that new generation fighter in 2035.

Saudi Arabia is keen to join that fighter project, and Italy backs Riyadh’s entry to that consortium, Reuters reported Jan. 27.

Dassault tucked its life-size model of the new generation fighter on the side of its outdoor stand, while its Neuron prototype for an unmanned combat aerial vehicle (UCAV) and a Rafale, complete with a spread of weapons, took pride of place in the front.

That layout was seen by some as relegating the new fighter to second place, while pointing up the perceived importance of the Rafale and its accompanying collaborative combat aircraft (CCA), or combat drone.

Trappier’s remarks to Bloomberg did not surprise one French executive, who said those sentiments had appeared in the French press, and perhaps the high media impact stemmed from being expressed in English.

The Dassault executive told June 16 Le Figaro, a daily, the French company’s minority position on the fighter made it “particularly complicated to exercise leadership. If the states want us to go ahead, governance needs to be changed.”

The Dassault family owns Le Figaro.

The aim was to build and fly a plane by 2029/30, he said. “To do that, a leader is needed, not endless discussion on the work share for the nations. This geographic return is not efficient.

That was fine when the work was all on paper, but when it came to ‘cutting steel,’ things had to change,” he said.

The Dassault top executive made it clear April 9 to the defense committee of the lower house National Assembly, when he told parliamentarians “the task is extremely difficult,” but the company had no intention of pulling out.

There was permanent negotiation, he said, with a long and complex path.

“I am not sure this is the model of efficiency, but we will meet the wishes of the states,” he said.

There were delays due to the geographic return approach, he said, when the priority should be on the level of expertise to develop an ambitious industrial product. That product should be competitive, not only with the enemy but also what the allies were building.

Dassault could not build everything, but the company did work with Thales, the electronics company, he said.

The family-controlled plane maker holds 26.6 pct of Thales.

The fighter project lay in finding the best compromise between stealth and maneuverability, while meeting requirements of the chiefs of staff, he told parliamentarians. Tests should be launched as soon as possible, and he favored speeding up the project by a revised share of “responsibilities.”

“It is up to the states to discuss, to define the best way to manage this ambitious program,” he said.

“I do not want to appear arrogant,” he said in answer to whether Dassault could build the FCAS on its own. “I am ready to cooperate and share, but Dassault and its partners Thales and Safran have the capability to build a fighter jet on a national basis.

“The president strongly wishes to see cooperation on FCAS,” he said, as the three partner nations allowed increased funding and the fighter would signify a more united Europe.

“The state is committed, but the situation is more complex when one plunges into the reality of contracts,” he said. “I say again – with three, the situation is necessarily more complex, and should evolve.”

President Emmanuel Macron and the then German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, announced in 2017 the determination to launch the FCAS project, soon after a U.K. referendum delivered a vote, with narrow margin, to leave the E.U.

The FCAS budget for the present phase 1B and upcoming phase 2 was worth almost €8 billion ($9.2 billion), the armed forces ministry has said. Phase 1B was worth €3.2 billion, ran 2023-2025, and allowed air force officers to select the aircraft architecture this year.

Phase 2 calls on the partner companies to build and fly a fighter technology demonstrator and two classes of remote carriers, or drones, in 2028/29. That appears to have slipped to 2029/30.

Belgium, an observer on FCAS, is keen to join as a partner nation when phase 2 is launched, opening up the prospect for work for Belgian aerospace companies.

The FCAS budget shared between the three partner nations has been estimated at some €80 billion, and that appears to have been rounded up to €100 billion.

The new fighter would replace the Eurofighter Typhoon for Germany and Spain, and the Rafale for France. The FCAS project includes a combat cloud for extended command and control, as well as the swarm of drones.

Featured image: The Paris Air Show 2025 as seen from the Dassault Pavilion. Credit: Dassault.

U.S. Marines with Logistics Operations School conduct helicopter support team training at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, March 18, 2025. The HST training is designed to prepare Marines to manage activities at landing zones and to facilitate the pickup, movement, and landing of helicopter-borne troops, equipment, and supplies.

CAMP JOHNSON, NORTH CAROLINA,

03.18.2025

Video by Lance Cpl. Brant Cushman

Marine Corps Combat Service Support Schools

By Debalina Ghoshal

Modern warfare operates in an increasingly contested environment where adversaries possess not only advanced weapon systems but also sophisticated cyber capabilities that can disrupt critical defense technologies.

The complexity of contemporary missile defense systems requires seamless integration between multiple subsystems and the main weapon platform.

As demonstrated during Operation Sindoor, the transition from weapon induction through deployment to active employment demands robust networking capabilities that can maintain operational integrity under hostile conditions.

Blockchain technology emerges as a promising solution to enhance the reliability and security of missile defense systems.

This article examines how blockchain can strengthen missile defense capabilities by improving data integrity, securing communications, and creating resilient command structures.

Blockchain technology provides missile defense systems with two critical capabilities: maintaining data integrity and securing communications during crisis operations. By implementing a controlled blockchain mechanism, military forces can ensure that essential operational data remains accessible across multiple domains while enabling efficient networking between subsystems and primary weapon platforms.

Traditional centralized command and communication structures present significant vulnerabilities in contested environments. A centralized system creates single points of failure that adversaries can exploit through cyber attacks, potentially compromising entire missile defense networks.

Blockchain addresses this vulnerability by enabling decentralized command and communication architectures. This distributed approach makes it substantially more difficult for adversaries to disrupt missile defense operations, as they would need to compromise multiple nodes throughout the network rather than attacking a single central point. The implementation of strong cryptographic algorithms further protects sensitive information and restricts unauthorized access during critical operational periods.

This decentralized structure supports a “defense by denial” strategy, preventing adversaries from neutralizing defensive capabilities to enable their own offensive operations.

Missile defense systems undergo distinct operational phases from initial fielding through deployment to active employment. Blockchain technology facilitates smooth transitions between these phases by preventing data tampering and maintaining comprehensive integrity records throughout the system lifecycle.

One of blockchain’s significant advantages lies in its ability to maintain complete maintenance records within the distributed ledger system. These comprehensive records prove invaluable during system upgrades, technological modifications, and eventual decommissioning processes. When acquiring new missile defense capabilities, historical maintenance data helps military planners understand existing system limitations and specify requirements that address these shortcomings.

During peacetime, missile defense systems require frequent testing to ensure operational readiness. Blockchain-enabled data management systems can effectively capture, store, and analyze test data, providing insights that enhance system performance and reliability.

In crisis situations, blockchain systems enable rapid data coordination by sharing minimal but critical information packets that support split-second decision-making processes. Post-engagement data analysis helps military commanders assess mission success or failure and refine future operational strategies.

Blockchain technology offers significant potential for arms control verification processes. The technology can provide transparent, tamper-proof records of launch platforms and interceptor systems, facilitating effective verification mechanisms. This capability supports both crisis management and peacetime monitoring requirements.

The United States Navy is actively developing blockchain integration for its missile defense systems. The Simba Chain project focuses on supply chain security and data management for the Aegis ballistic missile defense system, ensuring secure supply lines and robust data handling capabilities.

Additionally, the Powerful Authentication Regime Applicable to Naval Operational Flight Program Integrated Development (PARANOID) program represents another blockchain initiative designed to secure weapon system software throughout development and deployment phases.

Despite its advantages, blockchain technology faces inherent limitations that create potential vulnerabilities in missile defense applications. The most significant concern involves the possibility of adversaries compromising a substantial portion of the blockchain network, which could disrupt the operational effectiveness of the entire missile defense system.

Other challenges include the computational overhead required for blockchain operations, potential latency issues in time-critical scenarios, and the need for robust cybersecurity measures to protect the blockchain infrastructure itself.

Blockchain technology offers compelling advantages for enhancing missile defense system security, reliability, and effectiveness. Its ability to provide decentralized command structures, maintain data integrity, and secure communications addresses many vulnerabilities inherent in traditional centralized systems. However, successful implementation requires careful consideration of the technology’s limitations and the development of appropriate safeguards to mitigate potential vulnerabilities.

As military forces continue to operate in increasingly contested environments, blockchain technology represents a valuable tool for maintaining defensive superiority and ensuring mission success in critical scenarios.

Debalina Ghoshal is Non Resident Fellow, Council on International Policy, Advisor, Indian Aerospace and Defence News and the of the book, “Role of Ballistic and Cruise Missiles in International Security.”

U.S. Marines with Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron (HMH) 461, Marine Aircraft Group 29, 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing, and 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, fly in a CH-53K King Stallion during the air assault portion of Marine Air-Ground Task Force Distributed Maneuver Exercise 1-25 at Marine Corps Air-Ground Combat Center, Twentynine Palms, California, Feb. 11, 2025.

MDMX prepares Marines for future conflicts by combining constructed virtual training with offensive and defensive live-fire and maneuver training scenarios. Service Level Training Exercise 1-25 is designed to enhance readiness across core Mission Essential Tasks and prepares the MAGTF to execute distributed operations across vast, diverse environments by emphasizing decentralized command and control.

TWENTYNINE PALMS, CALIFORNIA

02.11.2025

Video by Sgt. Makayla Elizalde

Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center

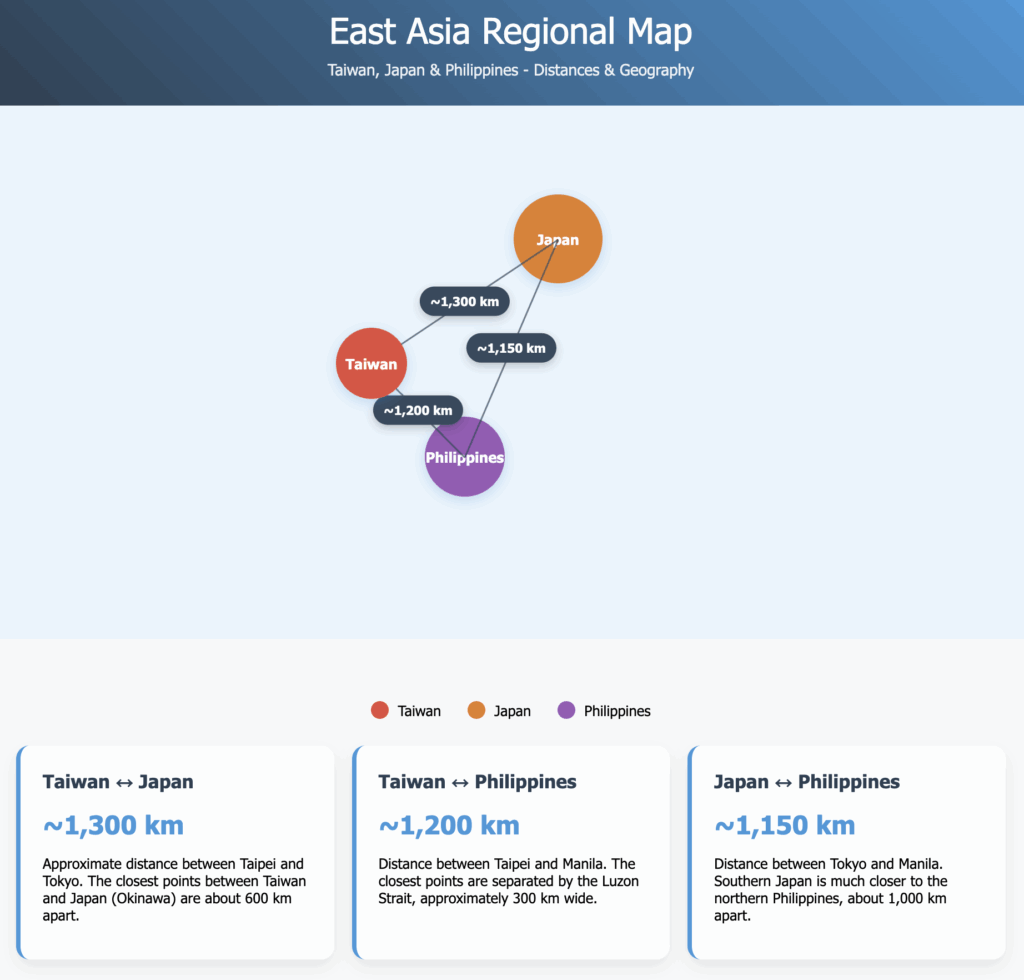

While Taiwan tensions are often viewed through a U.S.-China lens, the gravest strategic consequences would fall on Japan and the Philippines. Chinese control of Taiwan would fundamentally alter the regional balance, potentially isolating both nations and forcing them into accommodation with Chinese regional dominance regardless of U.S. positions.

Taiwan’s location at the center of the “First Island Chain” makes it a natural geographic chokepoint. The island sits at the midpoint between Japan’s Southwest Islands to the north and the Philippines’ Luzon archipelago to the south, creating what military strategists call the First Island Chain — a natural barrier that currently contains Chinese naval power within the South and East China Seas. This geographic position gives Taiwan outsized strategic importance far beyond its size.

Located opposite Fujian Province off the Asian continent, Taiwan is nearly the same size as Kyushu, measuring almost 36,000 square kilometers. It sits at the midpoint of the first island chain, the transnational archipelago running south from Japan through Taiwan to the Philippines. The loss of this central link would fundamentally reshape regional security dynamics.

Japan’s dependence on Taiwan Strait shipping routes creates an acute vulnerability that Chinese control would immediately exploit. CSIS estimates that 32 percent of Japan’s imports and 25 percent of its exports transit the Taiwan Strait, with over 95% of Japan’s crude oil coming from Middle Eastern countries and much of it transported through this route.

About 6 trillion cubic feet of liquefied natural gas, or more than half of global LNG trade, passed through the South China Sea in 2011. Half of this amount continued on to Japan, with the rest going to South Korea, China, Taiwan, and other regional countries. The geographic reality means that for Japan, roughly $13 billion of its imports also pass through the Luzon Strait, yet this is just a fraction of its imports through the Taiwan Strait.

The PRC views the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands as part of “Taiwan province” and may seek to take the islands during a conflict. If the PLA Navy were to occupy Taiwan, Japan would struggle to defend its westernmost islands, as well as the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, and even Okinawa. This connection transforms Taiwan from a distant concern into an immediate threat to Japanese territory.

The PLA’s shortest passages from China’s mainland to the Pacific Ocean are on the north and south sides of Taiwan. The former is through Japan’s Southwest Islands between Japan’s mainland and Taiwan, and the latter is through the Luzon Strait between Taiwan and the Philippines. Chinese control of Taiwan would breach this natural defensive barrier, fundamentally altering Japan’s strategic environment.

Any major armed contingency on or around Taiwan would present an economic and humanitarian crisis for the Philippines. As the nearest potential safe harbor, the volume of refugees escaping the conflict would be likely to quickly overwhelm Philippine capacity. The Marcos administration has acknowledged this reality, with the president noting that Taiwan’s proximity to Luzon makes it “hard to imagine” that the country could avoid conflict.

The strategic importance of the Luzon Strait cannot be overstated. Other straits bordering the South China Sea like the Malacca, Sunda and Balabac Straits are too narrow and shallow for submarines to pass through undetected. The Taiwan Strait is adjacent to and heavily monitored by China as well as by Taipei and the US. This makes Luzon Strait critical in all-out war because the nuclear submarines of both China and the US have a better chance of passing through it undetected.

The Luzon Strait is a choke point for access between the South China Sea and the Philippine Sea, and China’s navy uses it to move carrier strike groups and destroyers out to the open Pacific. Access to the strait is necessary for Chinese interests in the event of a Taiwan Strait conflict.

Chinese control of Taiwan would essentially bracket the Philippines between Chinese-dominated waters. The Philippines depends on the strait to transport about one-fifth of its global imports and one-seventh of its exports, but its geography allows it to send much of its trade through the Luzon Strait and Western Pacific Ocean. However, Chinese control of Taiwan would compromise even these alternative routes.

Chinese strategic thinkers explicitly view Taiwan as key to regional domination. Control over Taiwan would transform the Taiwan Strait into China’s “strategic inner lake.” Conversely, so long as the island remained out of China’s hands, it would expose the mainland’s coastal metropolises, seaborne commercial traffic, and the movement of air and naval forces to hostile forces located on Taiwan.

Beijing has long feared that a maritime coalition led by Washington might seek to choke off Chinese access to the seas in a war over Taiwan. Control of the island would thus “shatter the semi-sealed predicament of China’s sea areas” while transforming Taiwan, the central segment of the first island chain, from a barrier into a “portal” to the Pacific.

Chinese forces on the island would be able to radiate power along the first island chain and beyond. From air bases and airports on Taiwan, Chinese aircraft with combat radii of 2,000 kilometers would be able to cover the Yellow and East China Seas, the various straits from Bohai to the north to Bashi to the south, and the Ryukyus, Kyushu, Shikoku, and much of the Philippine archipelago.

The Taiwan Strait is the primary route for ships passing from China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan to points west, carrying goods from Asian factory hubs to markets in Europe, the US and all points in between. Almost half of the global container fleet and 88% of the world’s largest ships by tonnage passed through the waterway.

If cross-strait tensions become especially dire, cautious shipping companies may avoid routes near Taiwan altogether. That same vessel departing from Singapore may choose to sail south of the Philippines before heading north through the Miyako Strait to reach South Korea. This would extend the journey by roughly 1,000 miles, adding significant costs and delays.

Even alternative shipping routes would face Chinese pressure. Many countries would feel the effects of these disruptions, but two key U.S. allies, Japan and South Korea, would be among those most impacted. It would also likely make it infeasible to stop at Chinese ports while en route, which could have significant ripple effects on supply chains given China’s central role in maritime shipping.

Recent remarks from Japanese leaders do not mean Tokyo has pledged to defend Taiwan if China attacks, or that it necessarily commits to supporting the United States militarily if Washington chooses to get involved. Tokyo’s answer would ultimately depend on top-level political judgments about the conflict’s cause, specific nature, and implications for Japan’s peace and security.

However, Current Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has pledged to double Japan’s defense spending in response to the tense security climate, indicating growing recognition of the stakes involved.

The Philippines has a special economic relationship with Taiwan, but acknowledges the People’s Republic of China (PRC), rather than the Republic of China (Taiwan), as the sole political government of China, and has consistently affirmed the “One China Policy”. However, the Philippine government is now paying more attention to developments in the Taiwan Strait. With the Marcos Jr. Administration, a China policy will likely always be two-pronged: with one prong oriented to Beijing, and another toward Taipei.

Philippine Defense Secretary Gilberto Teodoro said that the region is the “spearhead of the Philippines as far as the northern baseline is concerned,” and that its garrison would be strengthened, reflecting growing awareness of the Luzon Strait’s strategic importance.

Both countries are deepening security ties with the United States. U.S. Marine Corps anti-ship missiles will deploy to the Luzon Strait, a strategic first island chain chokepoint between the Philippines and Taiwan, during Balikatan 2025. The 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment’s Medium-Range Missile Battery will send Naval Strike Missile-equipped systems to the Luzon Strait.

The fourth Taiwan Strait crisis also further motivated Washington to strengthen its alliance with regional powers such as Japan, Australia, and the Philippines.

Beyond the strategic calculations, the fundamental issue is a question of values. Taiwan is a democratic state and has proven that Chinese culture can embrace democratic values. This is an affront to President Xi and his ideology of authoritarian control and global expansion.

Without any question to assault of Putin and Xi would have a similar motivation, namely, to expand their empires and to recover what is “rightfully theirs.” This is of course true if you are working to create a new global order where middle power democratic states like Australia and Brazil are consider merely commodity providers to the expanding Chinese empire.

In short, while U.S.-China competition dominates headlines about Taiwan, the most profound strategic consequences would fall on Japan and the Philippines. Both nations face the prospect of being isolated from each other and from broader alliance networks, potentially forcing accommodation with Chinese regional dominance regardless of US positions.

China is engaged in a geopolitical competition with the United States and a widening array of allies and partners — Japan and the Philippines most of all — who see their national interests directly threatened by Beijing’s choices. The geographic reality of Taiwan’s central position in the First Island Chain means that its fate will determine whether Japan and the Philippines remain sovereign actors in an open regional order or become subordinated to Chinese regional hegemony.

Understanding Taiwan through this regional lens — rather than purely as a U.S.-China issue —reveals why both Japan and the Philippines are quietly but significantly building defensive capabilities and strengthening security partnerships. For them, Taiwan is not just about U.S-Chinese competition; it is about their fundamental security and sovereignty in the decades ahead.

And for some earlier thoughts during Trump’s first term:

https://breakingdefense.com/2016/12/taiwan-trump-a-pacific-defense-grid-towards-deterrence-in-depth/

And more recently:

Taiwan, U.S. Defense Industry, and the Evolving Strategy for Indo-Pac Defense

By Robbin Laird

In late 2020, Murielle Delaporte and I published our book entitled: The Return of Direct Defense in Europe: Meeting the Challenge of XXIst Century Authoritarian Powers. A major emphasis in that book was that the broad challenge was inclusive of European infrastructure and the clear need for the European Union to focus on defense of infrastructure as a core mission rather than being future military force planners.

Recently, The Wall Street Journal published an insightful piece on Europe and the question of their maritime ports in an age when authoritarian powers are engaged and threaten at the same time those ports.

So what would you get if you combined our earlier analysis with this WSJ analysis of the current situation?

I decided to do just that and this is the result of doing a juxtaposition of the two analytical efforts.

How the continent is racing to secure its ports, supply chains, and strategic assets against dual challenges from authoritarian powers

Europe finds itself confronting an unprecedented dual challenge to its critical infrastructure: immediate military threats from Russia requiring urgent port and transportation upgrades, while simultaneously grappling with long-term strategic vulnerabilities created by decades of Chinese and Russian investment in European infrastructure.

The Immediate Crisis: Militarizing Europe’s Ports

The urgency of Europe’s infrastructure challenge became starkly apparent in recent NATO planning discussions. At the upcoming NATO summit, alliance members are targeting a dramatic increase in military spending from 2% to 5% of GDP, with 1.5% specifically allocated to what officials term “nonlethal domains” – cybersecurity, infrastructure, roads, railroads, and critically, ports.

The European Union has proposed an unprecedented €75 billion ($86 billion) investment over five years to upgrade transport infrastructure for military use, representing a massive leap from the current €1.7 billion military mobility budget. This reflects a sobering recognition that Europe’s ports have become potential chokepoints in any future conflict with Russia.

European officials and NATO planners have identified 500 critical locations across the continent requiring immediate upgrades to ensure rapid troop movement to eastern borders. The challenge extends beyond mere logistics – it encompasses the fundamental question of whether Europe’s commercial infrastructure can serve dual civilian and military purposes without compromising either function.

As Apostolos Tzitzikostas, the EU’s transportation commissioner, explains: “The ability to move troops and military equipment quickly across Europe is a military priority, but it is not just that. It is also essential for crisis response but also for making our transport systems smarter and stronger.”

The Convergence Challenge

The infrastructure crisis reveals what defense analysts call the convergence of cyber and physical vulnerabilities. As one expert noted, “Critical infrastructure is an area where the cyber and physical worlds are converging – the operation of digital systems affects our physical world, and so a cyber incident can have direct and serious physical impacts on property and people.”

This convergence is evident in Europe’s current port security initiatives. The European Maritime Safety Agency is working to identify cyber vulnerabilities in port systems, while the Nordic Maritime Cyber Resilience Center has specifically identified Russian hackers as a significant threat to European infrastructure and defense capabilities.

European officials suspect Russia is behind multiple incidents involving damaged or severed cables and pipelines under the Baltic Sea, part of what they see as a broader campaign to test and potentially compromise European infrastructure resilience.

The Long-Term Vulnerability: Foreign Investment in Strategic Assets

While Europe races to address immediate military infrastructure needs, a parallel challenge has been building for over a decade through Chinese and Russian exploitation of European free market mechanisms. Authoritarian states have systematically invested in and gained control over key European infrastructure, creating dependencies that could be leveraged during future crises.

The scope of this challenge is staggering. Chinese companies now control 29 ports and 47 terminals across more than a dozen European countries, including a 67% stake in Greece’s strategically crucial Port of Piraeus. In France, a Chinese consortium owns nearly 50% of Toulouse airport, located at the heart of the country’s aerospace industry.

The European Union’s belated recognition of this vulnerability led to the adoption in March 2019 of a new “framework for the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union.” This mechanism, comparable to the US CFIUS system, aims to monitor foreign investments that could affect security or public order.

The Nordic Model: Hardened Infrastructure as Standard

Some European nations are pioneering approaches that address both immediate military needs and long-term infrastructure security. Norway’s reconstruction of its F-35 air base at Ørland provides a template for how infrastructure development can prioritize security from the ground up.

The Norwegian approach emphasizes hardened facilities, secure supply chains, and workforce security. As Lt. Col. Eirik Guldvog explains: “The Armed Forces Estate Agency has built camps on the base to house workers to work on the base. Because of classifications, only Norwegian workers are being used.”

This model of “security by design” in infrastructure development contrasts sharply with the ad hoc approach of retrofitting existing commercial infrastructure for military use – the challenge now facing most European ports.

Balancing Security and Competitiveness

The tension between security requirements and commercial viability remains acute. Shipping executives fear that militarizing ports could undermine their competitiveness and deter private investment, particularly in facilities that might become targets during any future conflict.

As Katarzyna Gruszecka-Spychala, vice president of finance at Poland’s Port of Gdynia, notes: “We understand it’s needed, but still, we need to achieve competitiveness. Private investors could hesitate to put money into businesses that may be targeted by Russia.”

This concern reflects a broader European challenge: how to maintain the open, competitive markets that have driven European prosperity while protecting against authoritarian exploitation of those same market mechanisms.

The Path Forward: Integration of Security and Commerce

European officials argue that security and commercial interests can be complementary rather than competing priorities. NATO and EU planners believe that infrastructure upgrades designed for military logistics can simultaneously improve civilian traffic flows and economic efficiency.

The key lies in recognizing that robust, secure infrastructure has become a prerequisite for sustained economic competitiveness, not an obstacle to it. As the EU’s Tzitzikostas emphasizes: “These assets need to be competitive in peacetime and ready to defend European citizens when it matters most.”

A Continental Awakening

Europe’s current infrastructure crisis represents more than a response to immediate military threats – it reflects a fundamental awakening to the intersection of economic openness and national security. The continent that pioneered free trade and open markets is learning to defend these achievements against authoritarian powers that view economic integration as a vulnerability to exploit rather than a mutual benefit to preserve.

The success of Europe’s infrastructure security initiative will depend on its ability to maintain the delicate balance between openness and security, competitiveness and resilience. The stakes extend far beyond military logistics – they encompass the fundamental question of whether democratic societies can maintain their openness while defending against authoritarian manipulation.

As European leaders prepare for the NATO summit and finalize their massive infrastructure investments, they are essentially placing a bet on the possibility of “secure openness” – the idea that democratic values and market principles can coexist with the hard realities of 21st-century strategic competition.

U.S. Marines with Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM) 364, Marine Aircraft Group 39, 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing, extract U.S. Marines with 3d Littoral Combat Team, 3d Littoral Regiment, 3rd Marine Division from Calayan, Babuyan Islands, Philippines, during KAMANDAG 9, June 1, 2025.

KAMANDAG is an annual Philippine Marine Corps and U.S. Marine Corps-led exercise aimed at enhancing the Armed Forces of the Philippines’ defense and humanitarian capabilities by providing valuable training in combined operations with foreign militaries in the advancement of a Free and Open Indo-Pacific.

CALAYAN ISLAND, PHILIPPINES

06.01.2025

3rd Marine Aircraft Wing