By Murielle Delaporte

‘’Initiated and adopted by several nations in the past years, the concept of an Indo-Pacific theater does not mean the same for each one of them.

For France, which is the very first European nation to have replaced the traditional Asia-Pacific concept with a more assertive Indo-Pacific strategy, the key is the inclusion of India in the equation. The reason is tied to New Delhi’s political dimension which is crucial to counter-balance Beijing’s growing weight in this part of the world’’, explains a French submariner familiar with this region.

Balance is indeed the leit motiv in the current Macron government’s approach to foreign affairs.

Fearing an escalation fueled by increasing military expenditures and growing tensions while dreading a replay of the Cold War – this time between the United States and China – France is once again positioning itself as a ‘’stabilizing power’’ in a zone which ‘’spans from Djibouti to Polynesia’’, as stressed in the 2019 ‘’French Defence Strategy In the Indo-Pacific’’ official document.

The latter followed President Macron’s Australian Garden Island speech, which he made a year earlier on his way to make an official visit to India.

The 2018 statement highlighted the concept of a ‘’Paris-Dehli- Canberra axis,’’which his Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jean-Yves Le Drian had already promoted in 2016 when he was Minister of Defense in terms of a ‘France-India-Australia trilateral framework.

Sharing the exact same diagnostic as Washington (both under President Trump and President Biden) as far as the serious nature of Chinese aggressive action is concerned, the French government has not been shy in condemning Beijing on multiple grounds, ranging from the Uyghurs’ genocide to the Belt and Road Initiative.

Regarding the Indo-Pacific region, the concerns expressed by French officials are indeed specifically related to Beijing’s ability systematically to ‘’fill the vacuum’’ whenever an opportunity emerges and deny access to other players.

The ways and means progressively to evict other nations’ influence are limitless and include in particular:

- The polarization and militarization of international waters with the unilateral extension of territorial waters from 12 to 15 nautical miles (e.g., the Paracel Islands in 2017 in the South China Sea): according to a 2016 DoD estimate, 3,200 acres of land have been artificially created at the time.

- Investments in key strategic infrastructure via China’s One Belt One Road Initiative : the deep-water port of Kyaukpyu in Myanmar, the development of the Hambantota port in Sri Lanka or the operational control of the Gwadar port in Pakistan by the China Overseas Port Holding Company are all part of the Twenty-First Century Maritime Silk Road under way since 2013 designed to enhance connectivity throughout Southeast Asia, Oceania, the Indian Ocean, and East Africa.

- A growing military presence officially aimed at protecting Chinese communities abroad : the most telling example of such a strategic shift in Chinese military doctrine is the case of Djibouti. Beijing’s footprint – and foothold in the Western Indian Ocean – has been growing since 2008 through various investments in salt, railway, and the port of Doraleh. Its naval military presence has evolved from anti-piracy operations to the inauguration in 2017 of its very first overseas naval base, which currently hosts an estimated 2,000 troops but has a capacity of 10,000. In ten years – from 2008 to 2018 -, China’s 350-ship Navy trained about 100 ships and 26,000 sailors in the Gulf of Aden alone.

Such a trend privileging the policy of ‘’fait accompli’’ has been enhanced by the Covid crisis, during which China has been multiplying its military maneuvers in the straights of Taiwan, Miyako and Bashi, while the very first deadly border clash with India in 45 years occurred last June in the Himalaya.

‘’In a region including seven out of ten of the highest defence budgets in the world (the Unites States, China, Saudi Arabia, India, France, Japan and South Korea), strategic and military imbalances constitute an underlying danger with global consequences.

While several open crises persist and new rivalries emerge, the breakdown of strategic stability, or a lasting deterioration in the regional security environment, would have an immediate impact on France’s political, economic, and sovereign interests’’, states the above-mentioned 2019 “French Defence Strategy In the Indo-Pacific” official document.

Having appointed last November and for the first time an Ambassador for the Indo-Pacific, France is indeed a riparian and sovereign Indo-Pacific nation with clear vested interests starting with the protection of some 1.6 million French citizens leaving in its seven overseas regions, departments and communities (called DROM-COM in French for ‘’Départements ou Régions français d’Outre-Mer’’ and ‘’Collectivités d’Outre-Mer’’).

In the Indian Ocean are Mayotte, Reunion, the French Southern and Antarctic territories (Kerguelen, Amsterdam and Saint-Paul islands, and the Crozet islands). In the Pacific are New Caledonia, Wallis & Futuna, and French Polynesia. In addition, 200.000 French citizens settled in the littoral countries of the Indian Ocean, in Asia and Oceania. Far away and tiny for some of them, these territories nevertheless represent all together 93% of France’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (9 out of 11 million square kilometers), making it the second in the world after the United States.

Stability, with the defense of Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC), and, more generally, of the Global Commons at a time when military competition knows no boundary and opens new ones ranging from seabeds to exoatmospheric altitudes, is indeed a main concern shared not only by Paris and Washington, but also and foremost by the regional players in the Indo-Pacific.

How to reduce threats in order to enhance stability and promote the ‘’new Golden age’’ many experts foresee in that part of the world is however where differences of approach compete.

Forging Alliances Among Like-Minded States

‘’The French strategy in the Indo-Pacific region lies on three axes: developing joint crisis management tools, enhancing bilateral relations and fomenting a rule-based multilateral framework’’, describes a French diplomat formerly based in Beijing.

Reviving multilateralism in an inclusive manner as a way to contain a potential ‘’Great Power Competition’’ clash or growing tensions is where France and the United States has till now differed since Washington’s position under President Trump was aiming more towards a policy of isolation against China.

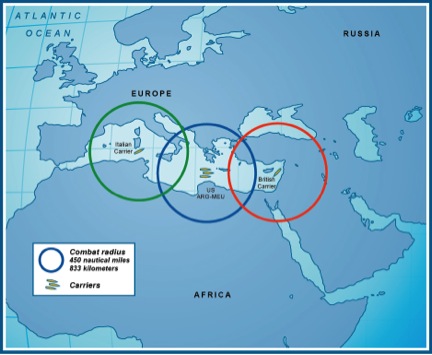

This difference of approach has been highlighted in diplomatic terms, but tends also to translate in the military posture of both countries in the region (all proportion kept of course) : ‘’When the U.S. Navy will choose to deploy an aircraft carrier, the French Navy will show its willingness to defend the freedom of navigation (e.g. in the strait of Taiwan where for the first time a French Frigate – the Vendémiaire – was blocked by the Chinese Navy in April 2019) using a frigate or an amphibious assault helicopter carrier (PHA in French for ‘’porte-hélicoptères amphibie’’) and choosing to sail a straight course rather than demonstrating a more assertive posture’’, notes the French Commander.

Having concluded a strategic partnership with China along with the ones negotiated with India and Australia, France advocates less a policy of containment than a policy of coercion which does not preclude commercial ties.

A form of ‘’Realpolitik’’ or ‘’Pacific coexistence’’ which resonates with many of the states leaving in the region which economies are heavily dependent on good relations with China.

Clearly the more ‘’like-minded’’ states the better to counter Chinese illegal endeavors in the region. ‘’Paris favors a regional multilateralism which is ideal to promote ad hoc structures best suited to address the challenges in this part of the world whether humanitarian, health-related, digital, environmental or else.

Last September, was held for instance the first trilateral meeting between France, India and Australia with the participation of the General secretary of the minister of foreign affairs.

The goal is to include Japan next. More multilateral coordination for a common action to be effective is necessary’’, stresses a French Quai d’Orsay official. Hence Paris’ recent request accepted last September to become a partner to the existing ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), a multilateral framework created in 1967 (two years after France’s withdrawal from the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization or SEATO – i.e., the equivalent of NATO in Asia – because of disagreements between France and the United States over Vietnam).

In addition, Paris has been developing strong bilateral relationships over the years – in particular with India, Australia (both countries with which Paris has concluded global strategic partnerships) and more recently with Japan – as well as various fora of discussion ranging from commercial and technological exchanges, climate change and natural disaster anticipation, to the fight against transnational threats (illegal traffics, criminality, jihadism, etc.).

France is for instance – in chronological order and in a non-exhaustive way – a member of the Western Pacific Naval Symposium since 1988, concluded the FRANZ agreement with New Zealand and Australia for disaster relief in 1992, the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) established in 1997, as well as the Quadrilateral Defence Coordination Groupe with the United States, Australia and New Zealand since 1998. France is also a founding member of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) established in 2008, belongs to the South Pacific Defence Ministers mechanism since 2013, as well as the Pacific Islands Forum with the participation of both New Caledonia and French Polynesia since 2016.

Because France has been itself a medium-sized Pacific power for more than two centuries, it feels directly threatened by the growing instability impacting its territories and communities, some of them in risk of vanishing because of climate change and consequent water rising.

Strengthening strategic autonomy is also a shared concern, hence the well-known Rafale deal with India and submarine ‘’deal of the century’’ with Australia. But military ties between France and its main allies in the Pacific go increasingly way beyond industrial partnerships towards more comprehensive operational relations between not only “like-minded” states, but also comparable military formats.

Enhancing Joint Indo-Pac Power Projection

Protecting the sovereignty of its territories and the growing number of French citizens leaving in them always required an adequate military force composed of forward-based assets and troops. These ‘’prepositioned’’ forces are called ‘’presence forces’ and include 7 to 8,000 permanent troops, as well as 700 temporary deployed personnel.

They are organized under five commands, three sovereign – in the Indian Ocean in Reunion and Mayotte (FAZSOI) and in the South Pacific in New Caledonia (FANC) and French Polynesia (FAPF) – and two in foreign countries – Djibouti (FFDj) and the United Arab Emirates (FFEAU) – for a ‘’permanent deployment in the Northern Indian Ocean’’, as described by the French Ministry of the Armed Forces.

It is from the latter that the French armed forces participate to Allied operation Inherent Resolve against Daesh, and, before that, to Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan (till 2012).

Very much like most NATO forces, the overseas sovereign forces were rather neglected in the name of the Peace dividends and a false sense of security. Although ‘’absolutely crucial to defend sovereign interests and participate to ad hoc coalitions’’, as pointed out by the above-quoted French naval officer, it is only in the past few years that they started to be modernized and built back close to their 2008 level, while power projection from the mainland has become increasingly visible and inclusive with more and more allies beyond the traditional four, i.e., the United States, India, Australia and Japan.

‘’As a maritime, air and spatial power, France possesses high level intelligence gathering means and significant force projection platforms. France is therefore able to contribute to each aspect of international security with its allies and partners.

France organizes regular multilateral exercises in the Indian Ocean (Papangue) and in the Pacific (Equateur, Croix du Sud, Marara). These exercises can gather up to several thousand military personnel coming from a dozen partner States.

France participates to many multilateral military exercises in Southeast Asia (Cobra Gold, Komodo, Pitch Black, Tempest Express, Coores, Marixs), in Northeast Asia (Khaan Quest, Ulchi Freedom Guardian, Key Resolve) and in the Pacific (Rimpac, Southern Katipo, Tafakula, Americal, Kakadu, Pacific Partnership). These exercises aim to increase mutual understanding and to create bonds between the different armed forces.

Many bilateral exercises are also organized at each French Navy and Air Force assets visits in the region. The regular high-level bilateral exercises Shakti (Army), Varuna (Navy) and Garuda (Air Force) embody the strategic partnership bonding France and India”, summarizes the 2019 “France and Security in the Indo-Pacific” official report.

In addition to the regular exercises traditionally organized in the Indian Ocean, such as the above-mentioned Varuna with India since 1993, as well as in the Pacific, such as the biannual ‘’Croix du Sud’’ humanitarian and relief exercise held from New Caledonia, what is interesting to highlight is the recent ability of the French armed forces to project faster and further both at sea and in the air from the continent. Strategic depth has become the name of the game for French military planners and the technology makes it possible today in unprecedented ways.

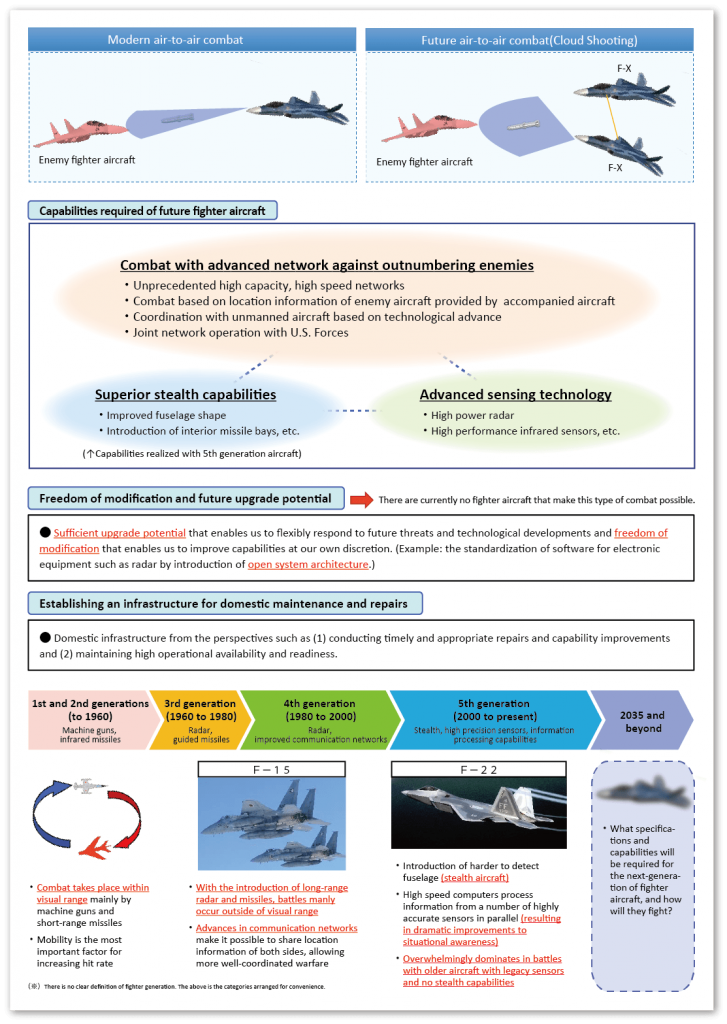

The acquisition of the A330 multirole Tanker Transport (MRTT) Phenix as well as of the A400M has for instance been game-changers for the French Air and Space Force which can now conduct long-range and in-depth raids.

The MRTT is an asset particularly important for the airborne strategic nuclear forces which are the ones conducting these type missions. In 2018 the ‘’Pegase’’ mission occurred in the aftermath to the French participation to the Australian ‘’Pitch Black’’ exercise. Launching a new type of Air diplomacy able to be mixed and matched with the more traditional naval diplomacy, ‘’Pegase’’ gathered three Rafale fighters, one A400M, one C-135 FR tanker and one A310 and 120 aviators and included stops in Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore and India.

It might be noted as well that the acquisition of the European tanker by the Royal Australian Air Force, in turn, has been a gamechanger as well for the Aussies. It has allowed them to marry up with their C-17s to have global lift and reach.

From January 20th to February 5th, 2021, the French Air and Space Force conducted a long-range mission called Skyros which started in Djibouti to go to India, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Greece and involved four Rafale, one MRTT, one A400M and some 170 aviators. In June another power projection mission called ‘’Heiphara’’, is planned in the Indo-Pacific deploying again 170 personnel, with this time four Rafale, two MRTTs and one A400M straight to Tahiti and back via Norfolk to celebrate the 240th anniversary of the battle of Yorktown in the Fall. As a French Air and Space Force officer stressed, ‘’These kinds of exercises allow to improve our interoperability: with a country like India which traditionally purchases a third of its military equipment from Russia, a third from Israel and a third from NATO countries, it is interesting for Rafale and Sukoi 3 to train as wingmen…’’

The same goes in the maritime theater where the French Navy conducts operations all the time, such as the current deployment of the Frigate ‘’Prairial’’ from Tahiti to monitor the embargo against North Korea in cooperation with Japan after a technical stop in Guam (a remake of the 2019 mission in that area).

The ‘’Marianne mission’’ which deployed for eight months and for the first time since 2002 a nuclear attack submarine, the ‘’Emeraude’’, with a support ship, the ‘’Seine’’, just ended and was aimed at enhancing cooperation with France’s main naval partners, Australia, the United States and Japan.

A few days ago, the yearly training mission ‘’Jeanne d’Arc’’ started and an Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) – including the PHA ‘’Tonnerre’’, the Frigate ‘’Surcouf’’, an amphibious task force armed with two ‘’Gazelle’’ helicopters – departed for a five-month deployment period (instead of the usual four) through the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the South China Sea, the Indian and Pacific Oceans. A mix of operational missions – counterterrorism, security, interoperability with NATO’s Combined task Force CFT 150, as well as humanitarian (with a Covid prism) – will be carried out, while conducting several bilateral exercises with some of the visited countries (Egypt twice, Djibouti, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Japan twice, Singapore, Malaysia, Sri Lanka). An amphibious exercise is for instance planned with the US and Japan in the Senkaku Islands in May.

If the defense of French interests in the Indo-Pacific region has been re-affirmed under the Macron presidency, it is done under the umbrella of the same desire to get other European nations to join forces all around the world – whether in Sahel or in the Levant region – in order to weigh more in front of abusive authoritarian powers and/or transnational violence, as well as in the counter-proliferation field given the coexistence of several nuclear powers in the Indo-Pacific region. Besides the United Kingdom, another traditional Asia-Pacific power, but because of Brexit, France was for a while the only European nation to have a specifically laid-out Indo-Pacific strategy. Not anymore: Germany designed last September its own Indo-Pacific strategic guidelines and sent a ship for a show of presence in what is considered today the world’s economic lung.

There has been increased concern about the rise of joint naval exercises carried by both China and Russia not only in the Western Pacific and South China Sea, but also in the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Baltics. Indeed, the Chinese entered the Baltic Sea for the first time during a Sino-Russian exercise called ‘’Joint Sea 2017’’. Two years later, “Joint Sea 2019” was the theater for the very first joint sea-based live-fire air defense exercise involving the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and Russian Navy. And this month, Russia, China and Iran are conducting joint naval exercise in the northern Indian Ocean.

The French government’s observation that a dangerous ‘’contraction of the geopolitical space’’ is taking place due to globalization, the impact of climate change on the maritime roads (e.g., the Chinese goal to link the Baltic sea region to the polar silk region in the Arctic) and new great powers’ military assertiveness is rooted in such drastic evolutions.

A lot more than the eye can meet is therefore at stake and that is what Paris hopes to convey during its next European presidency during which a common European Union Indo-Pacific strategy could be born adding a little extra-weight in a region striving for the right and perennial balance of power.

Featured photo: A French Air Force (Armée de l’Air) Dassault Rafale taxis after landing at RAAF Base Darwin in the lead up to Exercise Pitch Black 2018.

A condensed version of this article was published on Breaking Defense on March 11, 2021.