By Kenneth Maxwell

Calouste Gulbenkian set the rules for the division of the oil spoils in the Middle East in the aftermath of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

He did so under the “red line” self-denying agreement of 1928 between the major oil companies (including the America companies of Mobil and Standard Oil of New Jersey), which embraced the whole of the Arabian peninsula.

Gulbenkian, an Armenian Ottoman, who was educated at King’s College, London, and became and remained a British citizen, was a supreme shrewd persistent and highly litigious deal maker who carved up the Middle Eastern oil resources and took a five percent share of the profits through his Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC).

He became the richest man in the world in the process. His extraordinary story is the subject of superb recent biography by the historian Jonathan Conlin. After Gulbenkian’s death in 1955, the Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon where he spent his last years inherited Pandi, his London based holding company, through which Gulbenkian held his famous 5 per cent.

Thanks to the opening of the Kirkuk-banias pipeline (1952) and another line from Basra to Fao on the Persian Gulf, Pandi’s revenues increased dramatically during the 1950s. Iraq nationalized its oil resources in 1958 and was a founding member of OPEC in 1959, but Gulbenkian’s concessions in Oman and Abu Dhabi secured in 1937 and 1939 remained. Oil was discovered in Abu Dhabi in 1960, and in Oman, Gulbenkian’s 2 per cent of what became the Petroleum Development Oman became extremely profitable.

It was not until 2014 that the onshore Abu Dhabi Gulbenkian-era concessions expired.

In 1938 vast quantities of oil was discovered in Saudi Arabia. During WW2 President Franklin D. Roosevelt took over the financing King Abdul Aziz Ibn Said of Saudi Arabia from the British, and in 1944 Aramco was formed by renaming the Saudi subsidiary of Standard Oil of California (SoCal) and the Bahrain Petroleum Company which held a controlling position.

Vast oil resources were discovered at the Saudi Ghawar on-shore oil field, and in 1951 in the Saudi off-shore Sataniya field, the world’s largest oil field.

The government of Saudi Arabia took over Aramco completely in 1988. Saudi Arabia has the second largest proven crude oil reserves in the world.

The recent Abraham Accords signed between Israel and the UAE (United Arab Emirates) and Bahrain on September 15th, 2020 at the White House in Washington D.C., establishing full diplomatic relations and direct flights between Tel Aviv and Dubai and Abu Dhabi, made the UAE the third country In the Middle East after Jordan and Egypt to normalize ties to Israel.

These accords could well alter the geo-political dynamics of the Middle East in very important ways re-establishing old long forgotten connections which were unraveled in the aftermath of the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

Since 1948 Arab uprisings, wars, and foreign interventions, have all racked the region aggravating the old Sunni-Shite conflict and stimulating the ongoing conflict between the Islamic Republic of the Ayatollahs in Iran and the Saudi Arabia of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS).

The Dubai based port operator, DPWorld, has already said it would partner with Shlomi Fogel’s Israeli firm in a bid to take over Haifa Port which is being privatized with the Israelii government selling 100% of the shares in the Haifa Port Authority (HPC).

Haifa is the largest shipping hub in Israel. Shlomi Fogel is the co-owner of Israel Shipyards and of the Port of Eilat at the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea. DPWorld chairman and CEO, Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, has said that his objective is “to build trade routes between the UAE, Israel, and beyond, which will help our customers do business in the region more easily and efficiently.”

The UAE has constructed a Abu Dhabi Crude Oil pipeline to Fujairah on the Gulf of Oman which circumvents the choke point of Strait of Hormuz.

DPWorld has its eye on a seaborne route between Dubai and Eilat. The UAE is a major producer and exporter of petroleum and natural gas, most of it located onshore within Abu Dhabi. The UAE is the seventh highest total exporter of petroleum and liquified natural gas in the world. Shlomo Fogel has already set up a fund for Gulf States businesspeople to invest in Israeli high-tech companies.

Israel is an importer of petroleum and is dependent on oil for Russia and Kazakhstan which provide over 99% of Israeli consumption.

Israel had planned a new rail air and sea link to Eilat from the Jordan valley with the logistical center planned to be located in the desert to the north of Eilat, though the project was shelved indefinitely in 2019. The Chinese had expressed an interest in the rail route. The use of the port of Eilat has the advantage for Israel in that it avoids dependence on the Suez Canal. In the past, before the recognition of Israel by Egypt, the Egyptians had blocked the straights of Tirana where the gulf of Aqaba reaches the Red Sea hence cutting off access to Eilat.

The Israeli diplomatic opening to the UAE offers enormous commercial opportunities.

In particular it opens up access to the Indian Ocean routes where the UAE has long established relationships. 80% of the oil exported from the Persian Gulf goes to Asian markets: China, Japan, Indian, South Korea and Singapore. Questions remain about the role of Qatar and about Saudi Arabia. The UAE and Bahrain like the State of Israel all regard Iran as an existential threat.

Qatar, which is the host to the Doha based and Qatari-owned Al Jazeera television network, is involved in a dispute with the UAE (and Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and Egypt) which accuse it of supporting Islamic extremists and conniving with Iran. Qatar remained quiet on the UAE’s Abraham Accords, however, in talks with Palestinian chief negotiator, Saen Erekat, when he discussed in a phone call “developments on the Palestinian arena” with Qatar’s Foreign Minister, Mohammed bin Abdul Rahman Al-Thani.

Turkey and Qatar have signed a tripartite deal with the Libyan government for military cooperation in the Libyan government’s defense against the forces of Khalkha Haftar. Qatar will provide funding for military training centers and the establishment of a trilateral coordination center and Turkish base in the city of Misrata. Doha has an on-off relationship with Israel and has funded welfare programs in the Gaza Strip with Israel’s acquiescence. In 2019 together with the UN and Egypt, Qatar brokered a Gaza truce. Liquified natural gas (LNG) from Qatar provides more than 30% of the global trade.

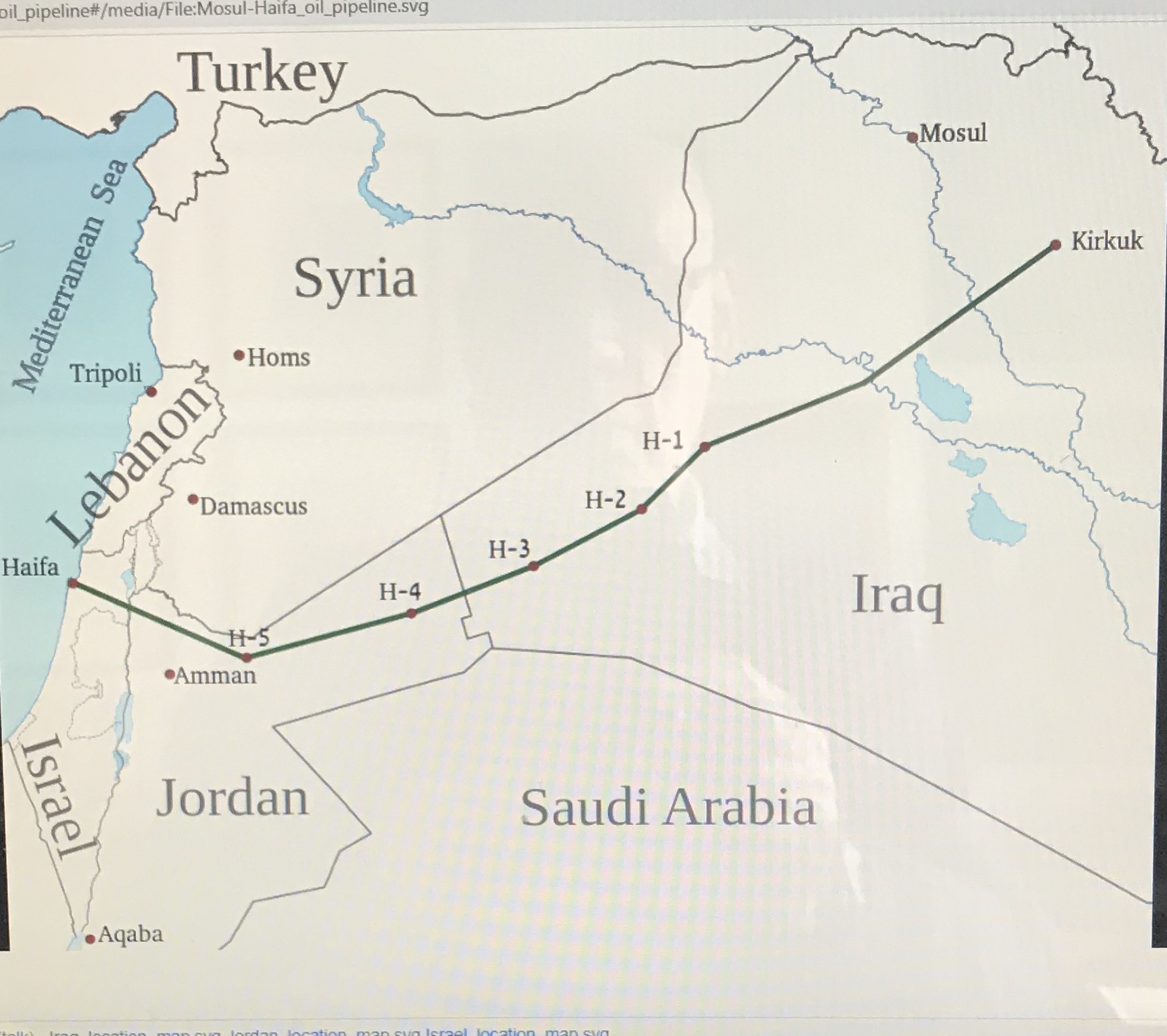

Israel had hoped to restart the Gulbenkian era abandoned pipeline from Mosul and Kirkuk in Iraq to Haifa.

This oil pipeline was originally built from the Ottoman vilayet in northern Iraq (Mosul and Kirkuk) and supplied the oil distilleries in Haifa between 1935 and 1948. This deal was brokered by Calouste Gulbenkian, who also assured that the vast oil fields of Mosel and Kirkuk become part of the post-WW1 and post-Ottoman empire Iraq, and not part of Turkey.

A second pipeline branched at Haditha in Jordan (pumping station K3) and took oil on to the coastal port of Tripoli in Lebanon. Originally this pipeline had been constructed to satisfy the demands (and the commercial oil interests) of the French mandate in Lebanon.

The pipeline to Haifa provided the fuel used by the British and American Armed Forces in the Mediterranean during WW2.

Haifa was the last British outpost turned over to the David Ben-Gurion in 1948. This pipeline was discontinued in 1948 when Iraq refused to pump more oil to the new State of Israel. Iraq has long depended on transnational pipelines to export its oil. After the abandonment of the pipeline to Haifa in 1948 a new pipeline was built to Baniyas in Syria and to Tripoli in the Lebanon. In 1977 a large pipeline joined the oil field of Mosul and Kirkuk to the Turkish Mediterranean coast at Ceyhan and Iraq ceased using the Syrian pipeline. In 1985 Iraq constructed a link to the Petrolina line across Saudi Arabia to the Red Sea port at Yanbu al Bahr.

All these routes have come problematic since the two Gulf Wars first in Kuwait and then in Iraq. Bagdad has been trying recently to develop gas exports routes again through Syria and Jordan.

The Iranians have also been seeking a route for the export of natural gas from their South Pars field through Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon to European markets. But the Syrian pipelines have been subject to sabotage.

And the Kurds in both Iraq (and in Syria) sit at an important junction in this scheme.

The Abraham Accords now offer a much better solution.

It may well lead to the reconstruction and reactivation of the 1,213-kilometer Trans-Arabian Pipeline (TAPLINE) from the main Saudi Arabia oil fields at Abqaiq, which was the southern terminus of TAPLINE, which ran west to Sidon on the Mediterranean coast in Lebanon. The Trans-Arabian Pipeline Company was originally a joint venture between Standard Oil of New Jersey (now ExxonMobil), Standard Oil of California (Chevron), Texas Company (Texaco now part of Chevron) and was managed the US company Bechtel.

The TAPLINE subsequently become fully owned by Aramco. It ceased to operate beyond Jordan in 1976 and the section between Saudi Arabia and Jordan was cut off in 1990 by Saudi Arabia because of Jordanian support for Iraq during the first Gulf War. When constructed it was the largest oil pipeline in the world. Oil was pumped though the TAPLINE until 20O2. It has been unfit for transporting oil since then. It was estimated in 2005 that it would cost some US$100 to US$300 million to rehabilitate the pipeline.

It has also been estimated that it would save 40% less to pump oil overland compared with the cost of oil shipped by tanker through the Suez Canal. Haifa would be the ideal Mediterranean terminal for Saudi oil. As it had been in the 1930s the ideal terminal for Iraqi oil. And of course, in theory it could become again. And in particular if Saudi Arabia should join the Abraham Accords.

The Abqaiq plant is the biggest Saudi Aramco oil processing and crude stabilization facility. Located in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia it is 25 miles (40 km) west of the Persian Gulf, close to Bahrain. The Abqaiq-Khurgis oilfield is among the biggest in the world. On September 14, 2019, drones attacked Aramco’s oil processing facilities at Abqaiq. The Iran supported Houthi movement in Yemen claimed responsibility.

Saudi Arabia said that the drones and cruise missiles were of Iranian manufacture. The result of the attack was to cut Saudi production by half effecting 5% of global supply. Uzi Rubin, the Israeli air and missile defense expert, said the attack was “a kind of Pearl Harbor”. US analysts concluded the attacks originated in Iran.

The Abraham Accords have significant geo-strategic implications.

Bahrain, where the US Fifth Fleet is based at Manama, provides US Naval Forces coverage of the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and Arabian Sea, and part of the Indian Ocean, and hosts the US Central Command. This is near the key Saudi oil fields. Bahrain is ruled by a Sunni dynasty, but the opposition is led by Shias and there have been clashes in the past.

But it is highly unlikely that Bahrain would have entered the Abraham Accords without Saudi approval.

The US Navy has also expressed concern with Chinese influence in the Haifa port complex.

The Shanghai International Port Group has been interested in the port of Haifa although it has run into the opposition of Israeli longshoremen. The ex-chief of US Naval Operations, Admiral Gary Roughead (USN ret’d), the former Chief of Naval Operations, has warned that Chinese “information and electronic surveillance systems jeopardize US information and cyber security.”

Haifa has regularly hosted American warship including the USS George W. Bush. The Chinese won a 25-year concession for Haifa’s new bay terminal in 2015 and will take over in 2021.

The U.S. has again recently raised concerns about China’s interest in the US$586m Haifa port sale. The UAE’s DPWorld and Shlomo Fogel since the Abraham Accords could be a much more acceptable alternative.

The Russians are of course well established at the Khomeini air base in western Syria’s Latakia Province and have a naval base at Tartus on the Syrian Mediterranean coast and last year Vladimir Putin committed to spend millions of dollars to modernize the port facilities.

Contingencies matter in history.

Benjamin Netanyahu, MBS, Donald Trump (and Jared Kushner) and the sheiks of the UAE and Bahrain, may none of them be “your cup of tea” as the saying goes.

But they have together, potentially at the very least, reset the geo-strategic equation in the Middle East in the most dramatic way since the establishment of the Jewish State in 1948. Calouste Gulbenkian undoubtedly would have appreciated the deal.

The slide show highlights the author’s sketches during a visit to Jerusalem in 1961; the two maps show pipeline routes from the 20th century.

The Trans-Arabian pipeline was originally projected to terminate in Haifa.

Also, see the following:

The Abraham Accords: What They Mean and Shaping a Way Ahead

A Look Back at the Remarkable Life of Calouste Gulbenkian