By Robbin Laird

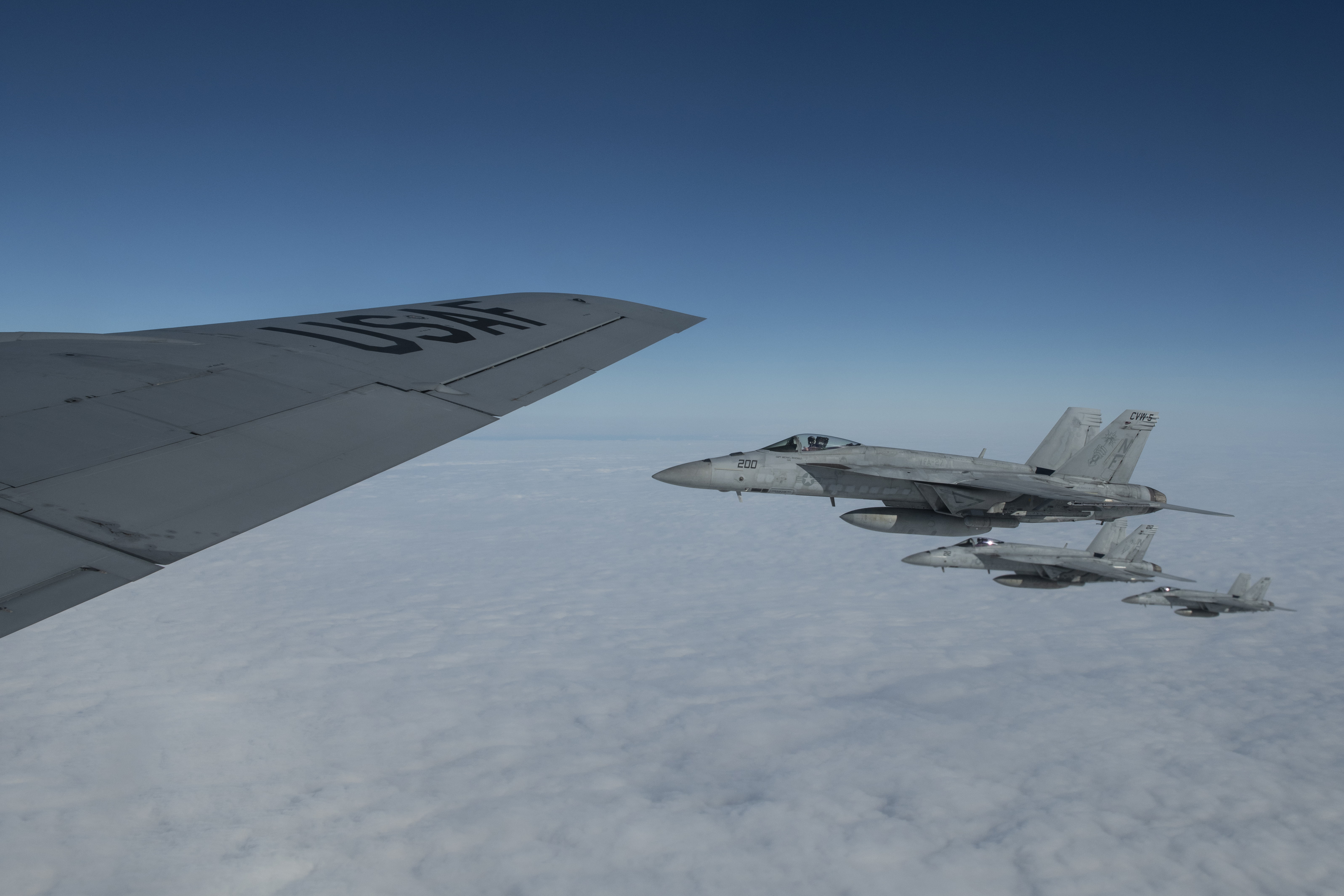

In my discussions earlier this year in San Diego with Vice Admiral Miller, we focused on the dynamics of change within and beyond the carrier air wing.

In that discussion, what was highlighted was a way to look at the shift from a legacy approach to the kill web approach, namely, the shift from the integrated to the integratable air wing.

That discussion highlighted that what is underway is a shift from integrating the air wing around relatively modest and sequential modernization efforts for the core platforms to a robust transformation process in which new assets enter the force and create a swirl of transformation opportunities, challenges, and pressures.

We discussed what might be called clusters of innovation, such as would be introduced as the MQ-25A Stingray comes onboard the carrier. In effect, the MQ-25 will be a stakeholder in the evolving C2/ISR capabilities empowering the entire combat force, part of what, in my view, is really 6th generation capabilities, namely enhancing the power to distribute and integrate a force as well as to operate more effectively at the tactical edge.

From this point of view, the MQ-25 will entail changes to the legacy air fleet, changes in the con-ops of the entire CVW and trigger further changes with regard to how the C2/ISR dynamic shapes the evolution of the CVW and the joint force.

The systems to be put onto the MQ-25 will be driven by overall changes in the C2/ISR force.

The cluster of innovation with the coming of the MQ-25A is being led by the transition from the legacy Hawkeye to the Aerial Refueling modified E-2D (AR) Advanced Hawkeye, which provides a game changing capability to a carrier air wing through advanced sensors & C2 networking capabilities, persistent presence, and greater operational reach.

That point was driven home to me in a discussion with CDR Christopher “Mullet” Hulitt, head of “CAEWWS,” the Navy’s airborne command & control weapons school located at Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC) at Naval Air Station Fallon.

As the cluster evolves, the notion of a platform-centric functional delivery of airborne early warning and battle management shifts to a wider notion of providing support to the distributed integrated combat force which flew off of the carrier and adjacent capabilities working with the air maritime deployed kill web.

We discussed a number of issues, and while I will not quote the CDR directly, I will highlight a number of takeaways from our conversation which provide insights into shaping a way ahead in the crafting, training and further developing of the integratable air wing.

The first takeaway is precisely the emergence of a different approach from the legacy Hawkeye to a new operational and training configuration.

With the coming of the MQ-25A Stingray and emerging integrated sensor and command & control capabilities, the “Airborne Early Warning” community has transitioned its role and title to reflect emerging roles and functions within a maritime kill web, with an Airborne Command & Control and Logistics Wing under the leadership of a Commodore, currently CAPT Matthew “Duff” Duffy.

The second takeaway is that with the coming of the F-35 to the carrier wing, there is a broader shift in working diverse sensor networks to deliver the combat effect which extended reach sensor networks can empower.

At Fallon, they are working the relationship between the F-35 and the E-2D and sorting through how to make optimal use of both air systems in the extended battlespace. Commander, Airborne Command & Control and Logistics Wing and Carrier Air Wing Two and are moving forward with a new initiative, the First Integrated Training Evolution (FITE), which will provide basic, tailored integrated training incorporating E-2D(AR) and F-35 paired with fourth generation platforms.

It is about deploying an extended trusted sensor network, which can be tapped through various wave forms, and then being able to shape how the decision-making arc can best deliver the desired combat effect.

The third takeaway is that the foundation is clearly being laid for the decade ahead for a fully operational maritime kill web.

The strategic objective is to be able to operate extended reach, integratable, and interconnected sensor networks that provide the reach of the air wing beyond where physically its flies to deliver an extended reach combat effect.

The fourth takeaway, one which I have spent a lot of time working on before, is that the radar on the advanced Hawkeye is not in any way a traditional radar.

The problem of terminology in discussing the new combat capabilities is certainly highlighted when discussing radars, built around modules which have a variety of combat capabilities built in, and in the case of the E-2D (AR) the traditional line between what airborne command & control, sensors, and electronic warfare systems do is clearly being subsumed into new integrative capabilities which can do more than the sum of the parts.

The fifth takeaway is that with the arrival of software upgradeable aircraft like the E-2D (AR), integrated with the MQ-25A, the entire process of evolving combat capabilities onboard an aircraft, and its ability to operate as an integratable of a kill web is changing significantly.

The goal is to get to the point where the core platforms are flexible enough to evolve software rapidly and interactively.

And rather than having to ensure that each platform is maximized for what it can do with organic systems, the approach would to determine which platforms with which capabilities can be a tasked for different functions and through integratability be able to contribute to a wider array of tasks as well.

For example, with the coming of the MQ-25A working with the E-2D(AR) , evolving the sensor loadout on the MQ-25A along with reach back to Triton can allow the E-2D (AR)to do core functions differently but also adjust how it can provide support for evolving C2 tasking as well.

Rather than following a classic AWACS like target identification and strike tasking function, the manned aircraft function will be to support the dynamic force packing function in the extended battlespace.

With regard to the E-2D (AR), the Navy is designing interfaces to manage the airborne MQ-25A.

And with the advanced Hawkeye, there is a shift to operating two aircraft at the same time, replicating to some extent the 4-ship formation approach of an F-35 whereby the four ships operate as one combat brain within the airspace in which they are operating.

This is a shift from the legacy Hawkeye where one aircraft operated off of the carrier to a seamless integration of a 2-ship formation of Advanced Hawkeyes.

The sixth takeaway is with the coming of the subsurface and surface weapons schools as participants in NAWDC the focus of operations for the E-2D(AR)/MQ-25A Stingray cluster will be open 360-degree domain knowledge and combat support to leverage assets through the maritime kill web.

The seventh takeaway is that the process of change we saw when visiting NAWDC a few years ago is accelerating.

What we saw then was shaping a way ahead to open the aperture of training to prepare for the coming of the F-35 and the focus on continuous development associated with the integratable air wing. In the case of CAEWWS, they will shortly have direct access to an integrated test configured aircraft.

This allows CAEWWS to operate an aircraft which is a baseline above the capability of what Navy operational test squadrons are flying.

This is especially crucial in an era of software block upgradeable aircraft.

NAWDC is in a position to release their recommendations concurrent with initial operational capability of a particular aircraft.

This means that when a new capability rolls out, they are able concurrently to provide vetted employment recommendations from NAWDC and its weapon school partners.

In short, the transition from core function platforms to working as enablers and nodes in a kill web is underway at NAWDC.

And the coming of the Advanced Hawkeye along with the Stingray in the same innovation cluster is a case in point.