By Robbin Laird

I have had a chance to visit with Rear Admiral Garvin and his team in Norfolk last Fall and earlier this year.

We discussed the evolving approach to theater ASW in those discussions along with the evolving approach to training and shaping an effective distributed maritime force.

We continued our discussion during a phone interview on April 30, 2020 and focused on the evolving capabilities of the Maritime Patrol Enterprise and its intersection with the distributed maritime force and a kill web concept of operations.

Rear Admiral Garvin leads the U.S. Navy’s global maritime patrol and reconnaissance enterprise.

This means that he trains, certifies and deploys the U.S. Navy’s Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Forces worldwide in support of theater Fleet and Combatant Commanders. This global oversight provides him a unique opportunity to focus on the entire scope of maritime operations, rather than focused narrowly upon one particular theater.

A 1989 US Naval Academy graduate, he witnessed the last 30 plus years of change in the political/military environment as a P-3 pilot. This meant as well that he was entering the force coincident with the perceived sunsetting of the Soviet Naval threat and transition to a new era of maritime patrol operations.

He began his deployed operational experience at Keflavik, Iceland as part of the US and NATO ASW force prosecuting former Soviet, now Russian submarines. Contrast this with his last operational deployment focused almost entirely on over land ISR contribution to CENTCOM forces.

Despite the decades-long increase in overland ISR and combat focused missions, the Navy did not abandon its key ASW mission set.

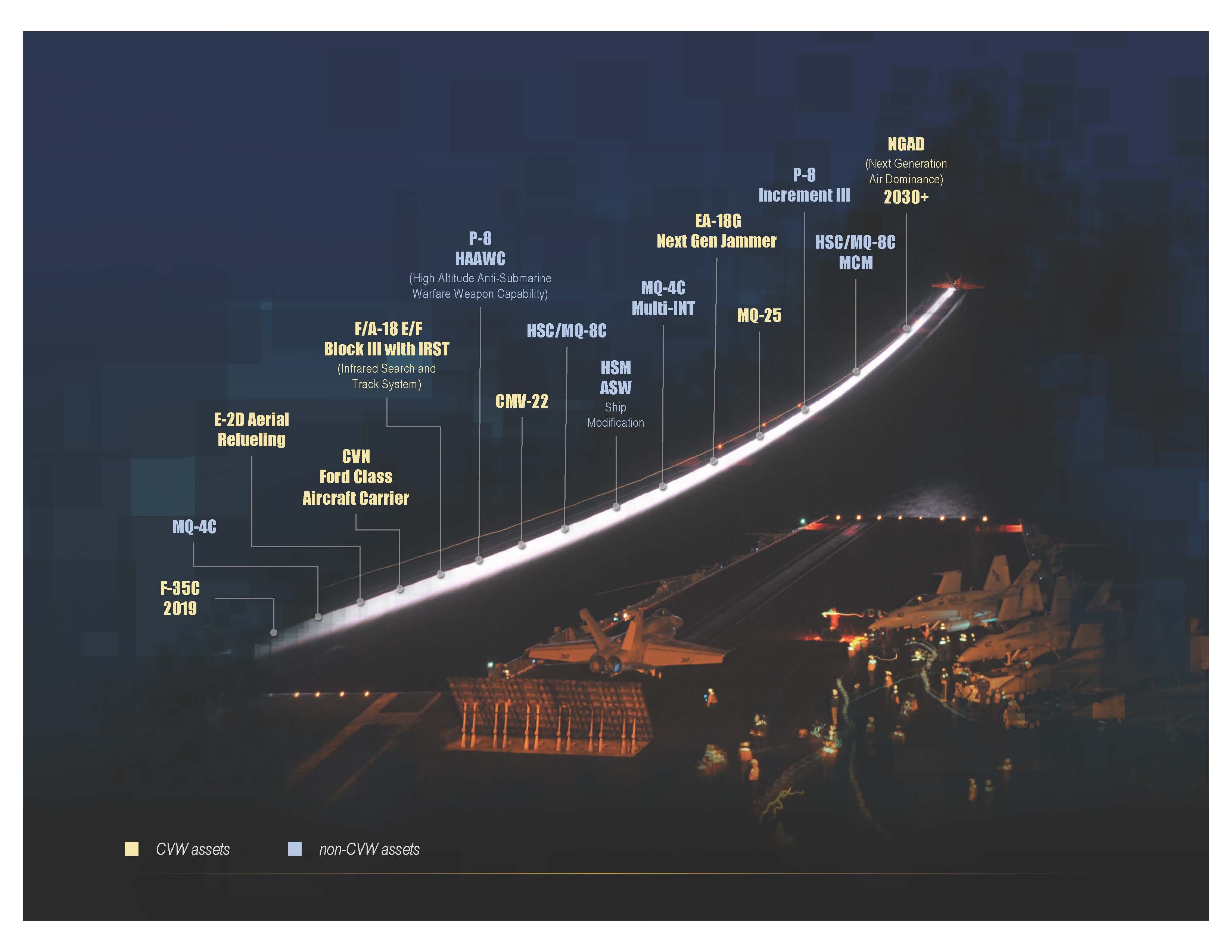

During my first discussion with a naval officer in 2011 about the coming P-3 to P-8/Triton transition, the Navy’s attention was focused squarely on delivering a new 21st century capability to effectively meet a growing ASW threat, and to do so via the kind of manned-unmanned teaming which the P-8/Triton dyad demands.

In that 2011 discussion with then Commander Jake Johansson, he highlighted how he thought P-8 would change the approach.

The P-8 gives you a range of capabilities that could be flexibly used in different ways. They will allow you the ability to fly from different bases farther from the fight. The ability to reach more distant operational areas may impact our onstation time but the increased reliability of the aircraft and the inflight refueling capability will ultimately result in a force with increased responsiveness as well as more capability and flexibility for Combatant Commanders.

We can protect our P-8 fleet a little bit better by having a little bit of distance between us and the fight as well. We will also be able to rapidly get into theater or into that area of responsibility that we need to be in, do our business and come back.

CDR Johansson then highlighted the potential synergy between BAMS, which has evolved into Triton, and the P-8 for the ASW mission sets.

I call them remotely-piloted, because it takes a lot of people to operate these systems. We moved to the family of systems (BAMS and P-8) because we felt that we could move some of the persistent ISR capabilities to a more capable platform, BAMS. BAMS long dwell time can provide the persistence necessary more efficiently than a rotation of P-8 24/7/365. Also, if we used P-8 to do that we would have to increase squadron manpower to give them the necessary crews to fly 24/7 MDA in addition to the ASW/ASUW missions.

We hope to have 5 orbits flying 24/7/365 to cover the maritime picture were required. The great thing about BAMS and P-8 is that they can work together to meet the COCOMS requirements. BAMS can provide the persistence and the P-8 can be used to conduct the specialized skill-sets that the BAMS cannot. BAMS can provide you the maritime picture while the P-8 either responds to BAMS intelligence or conducts ASW/ASUW.

This Family of Systems concept can become quite a lethal combination if we employ it correctly.

That was in 2011; now in 2020, I am talking with Rear Admiral Garvin and although the language has evolved somewhat, the operational experience being gained with P-8 and the coming of Triton certainly validates CDR Johansson’s forecast.

Question: In a way the approach we took with our allies to defend the GIUK, which included SOSUS, manned aircraft, and combat ships of various types, is being morphed today into a 360-degree manned-unmanned teaming tracking and kill web.

Is that a fair way to put it?

Rear Admiral Garvin: It is. We are following a similar mission construct working with our allies but the thinking and modality has advanced significantly.

“We are taking full advantage of the leap forward in many sensors and communications technology to interoperate in ways that were previously impossible. Faced with a resurgent and challenging ASW threat, we have not given up on the old tool sets, but we are adding to them and weaving them into a new approach.

“We are clearly shifting from linear or sequential operational thinking into a broader understanding and implementation of a web of capabilities.

“In the past, when operating a P-3, you operated alone, you had to be the sensor and the shooter. To be clear, it remains necessary that every P-8 aircraft and crew be ready and able to complete the kill chain organically, but the fact of the matter is that is not the way it always has to be, nor is it the way that we’re planning for it to have to be going forward.

“On any given mission, the P-8 could be the sensor and perhaps the allied submarine is the shooter. Or vice versa. Or maybe the destroyer is the one that happens to get the targeting solution and the helicopter is the one that actually drops the weapon. Sensor, shooter, communications node, or perhaps several at once, but each platform is all part of a kill web.”

Question: The P-8 and the Triton are clearly a dyad, a point often overlooked.

How should we view the dyadic nature of the two platforms?

Rear Admiral Garvin: There are several ways to look at this.

The first is to understand that both platforms are obviously software driven and are modernized through spiral development.

We focus on spiral development of the dyad in common, not just in terms of them as separate platforms. It is about interactive spiral development to deliver the desired combat effect.

“Another key element of teaming is that during the course of their career, the operators of P-8 and Triton have the opportunity to rotate between the platforms.

“This gives them an innate understanding of the mission set and each platform’s capabilities. They, better than anyone, will know what the dyad can deliver, up to an including a high level of platform-to-platform interaction. The goal is to be able to steer the sensors or use the sensor data from a Triton inside the P-8 itself.

“The idea of P-8 and Triton operators working closely together has proved to be quite prescient.

“Our first Triton squadron, VUP-19 is down in Jacksonville, Florida under Commander, Patrol and Reconnaissance Wing 11. And when we build out the full complement of Tritons, we’ll have VUP-11 flying out of Wing 10 in Whidbey Island, Washington. Triton aircrew literally work down the hall and across the street from their P-8 brothers and sisters.

“The Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance aviator of the future will be well versed in the synergy inherent in both manned and unmanned platforms.

“The unblinking stare of a Triton enhances the Fleet Commander’s MDA and understanding of an adversary’s pattern-of-life by observing their movements in the optical and electromagnetic spectrum.

“Moreover, Triton serves as a force multiplier and enabler for the P-8. Early in Triton program development, we embraced manned and unmanned teaming and saw it as a way to expand our reach and effectiveness in the maritime domain.

“One key software capability which empowers integration is Minotaur.

“The Minotaur Track Management and Mission Management system was developed in conjunction with the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory. Minotaur was designed to integrate sensors and data into a comprehensive picture which allows multiple aircraft and vessels to share networked information.

“It is basically a data fusion engine and like many software capabilities these days, doesn’t physically have to present on a platform to be of use.

“These capabilities ride on a Minotaur web where, if you are on the right network, you can access data from whatever terminal you happen to be on.

Question: With such an approach to integratabilty, then this allows the fleet to be able to collaborate with one another without each platform having to be topped up with organic generators of data and to have to maximize the sensor-shooter balance on a particular platform.

This then must provide flexibility as well when flying a dyad rather than a single aircraft to work a broad range mission like ASW?

Rear Admiral Garvin: It does.

It also provides for resiliency through multiple sensor points in the kill web empowering multiple kill points on that web.

“This begs the question, how much resiliency do you want to build in? Do you need several platforms that carry the actual data engine, with the rest of the force simply having access to data produced by the data fusion engine?

“It becomes a question of cost-benefit and how much resilience do you want to build into each individual platform.

Question: In other words, the new approach allows for a differentiated but integrated approach to system development across the force seen as interactive platforms?

Rear Admiral Garvin: I think of it this way, rather than taking an evolutionary or iterative approach, what this allows for is a step change approach.

“We’re thinking beyond just the iterative.”

This discussion with Rear Admiral Garvin drives home a key point for me that the MPA dyad operates in a way that is not simply a U.S. Navy capability for a narrowly confined ASW mission sets.

The USAF is clearly concerned with the maritime threat to their air bases and needs to ensure that a joint capability is available to degrade that threat as rapidly as possible to ensure that the USAF has as robust an airpower capability as possible.

Certainly, the B-21 is being built in a way that would optimize its air-maritime role. And clearly a core bomber capability is to get to an area of interest rapidly and to deliver a customized strike package.

Hence, for me the new MPA approach is a key part of the evolving USAF approach to future capabilities as well.

The color of the uniform perhaps belies how joint a kill web approach to platforms really is.

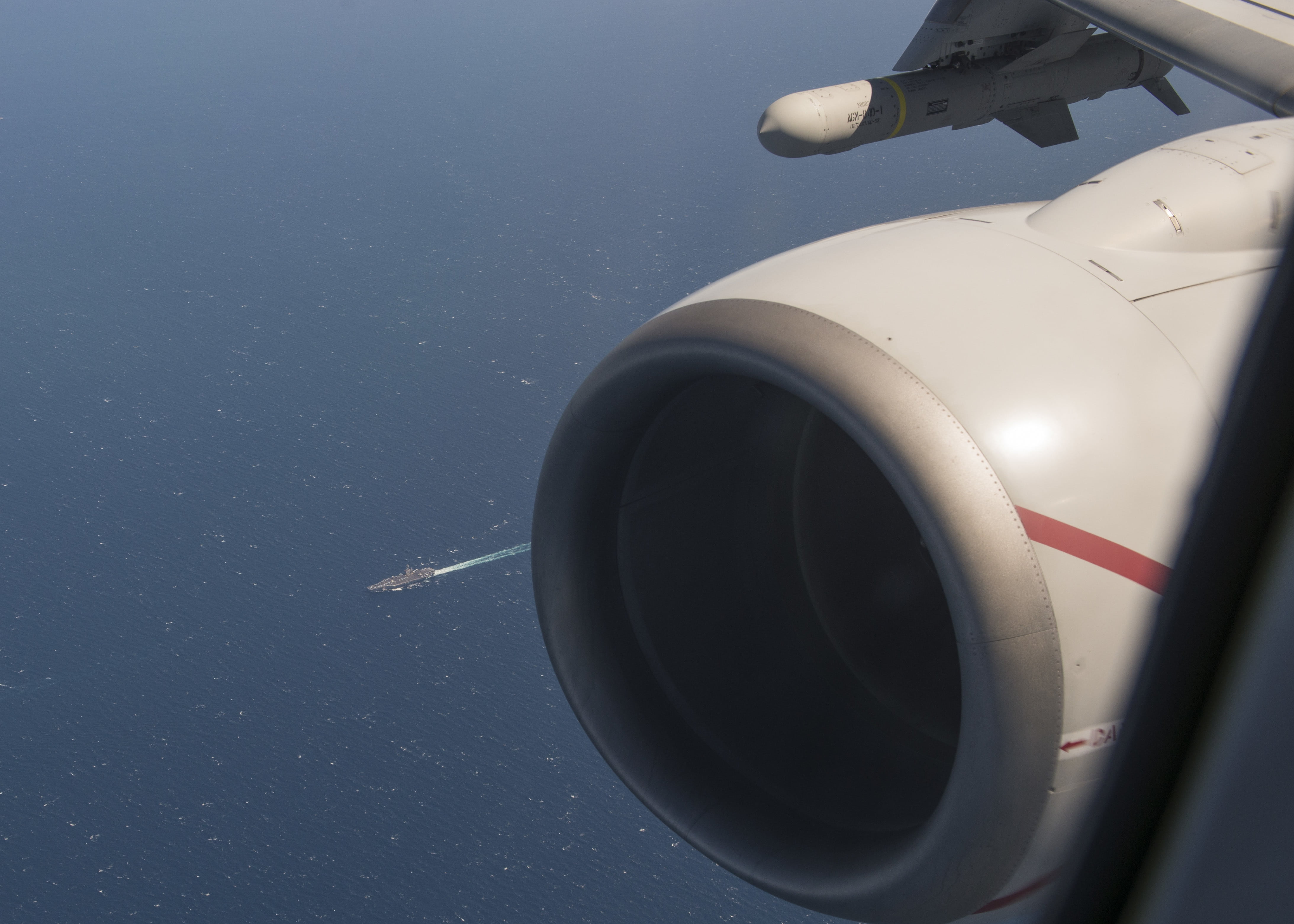

The featured photo shows the MQ-4C Triton preparing for a flight test in June 2016 at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Md. During two recent tests, the unmanned air system completed its first heavy weight flight and demonstrated its ability to communicate with the P-8 aircraft while airborne. US Navy photo.