I met with Asaf Punis, VP of Marketing and Business Development of Orbit at during the 2025 Navy League meetings held the first week of April 2025.

I was especially interested in talking with him because of my interest in C2 enabling a distributed kill web force. With the coming of maritime autonomous systems which can deliver mesh fleets to provide ISR and C for a distributed force, such capability dovetails in interesting ways as the LEO satellite networks evolve. This provides an incredible connectivity paradigm like to halves of clam shell providing ways to connect a distributed kill web force.

The company has developed a very small satellite terminal which can fit onto USVs, and as Punis informed me that there sat antennas offerings are built for a variety of platforms, but entail multi-domain, multi-mission operations.

He noted that their focus at the Navy league meetings was on their small and medium sized antennas for smaller maritime platforms.

He discussed their Multi-Purpose Terminal or MPT and this antenna can be installed on ground vehicles, on submarines, on small patrol vessels, USVs, autonomous ships, and can used for airborne ISR applications as well.

He underscored: “We use the same terminal in the different configurations but essentially the same terminal for each and every one of the platform segments.”

This obvious enhances sustainability of a force in terms of having commonality across the force, and for the manufacturer it provides for supply chain efficiencies as well. The two reinforce each other when considering a deployed force and its sustainment needs.

Their systems operate multi-band and very flexibly. As he noted: “In the past, a technician would have to go up the mast to change the band setting. Now you change bands automatically. You just push a button. The same antenna can operate both in GEO and MEO modes. This system is installed on ships of various sizes.”

As I mentioned at the Navy League event, they were focused on their smaller form factor. And this is how they described in the press release which they provided for the event.

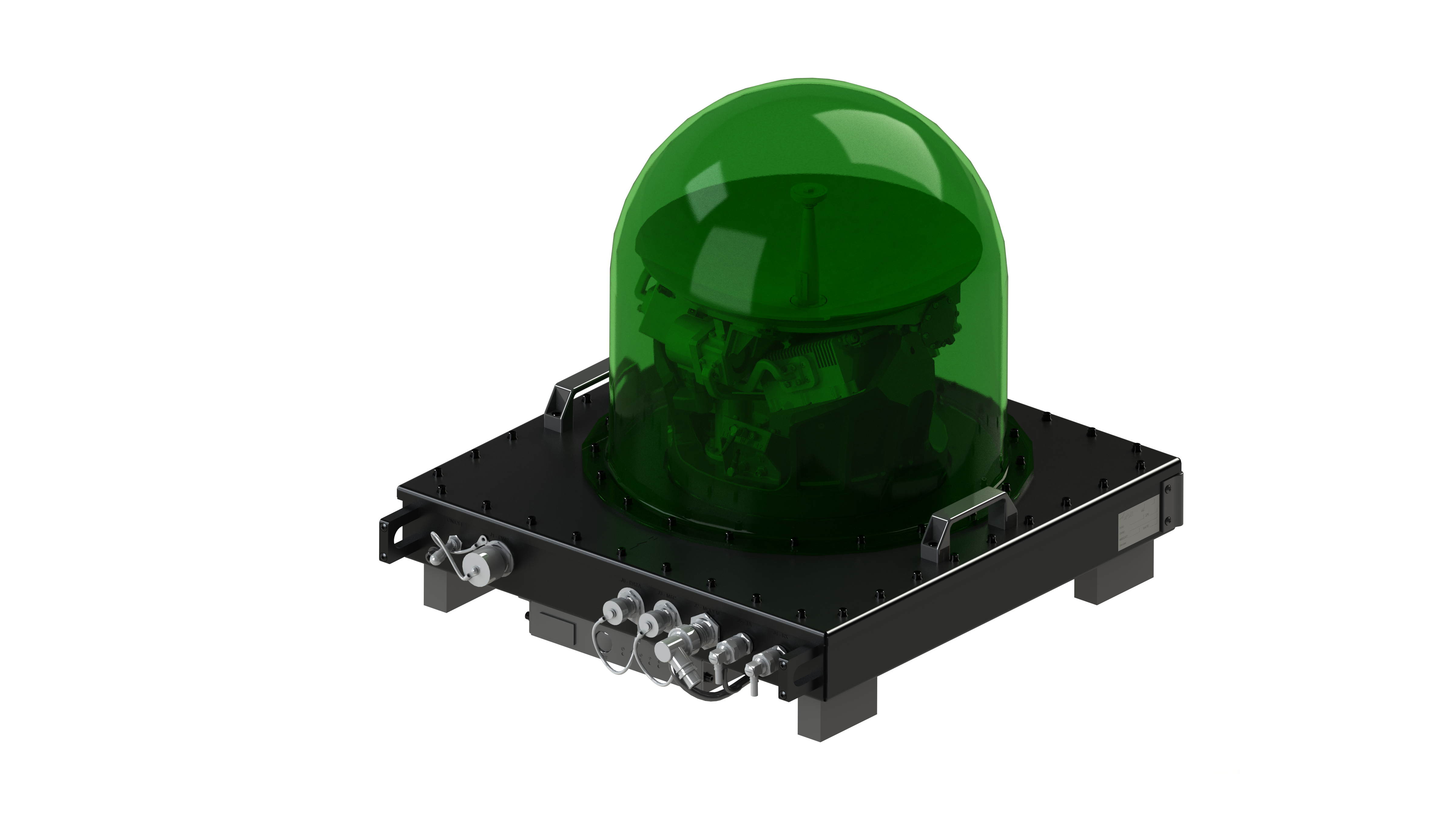

April 2, 2025 – Tel Aviv, Israel – Orbit Communication Systems Ltd. (TASE: ORBI), a leading global provider of ground, airborne, and maritime SATCOM terminals, tracking ground station solutions, and mission-critical communication systems, will highlight its MPT30Ka and MPT46Ka SATCOM Systems at Sea Air Space 2025. Specially designed for space-constrained platforms such as Unmanned Surface Vessels (USVs) and small naval craft and special forces operatrion, the MPT30Ka and MPT46Ka offer powerful, secure, and reliable satellite communication in a compact and lightweight form.

Based on Orbit’s battle-proven Multi-Purpose Terminal (MPT), the MPT30Ka and MPT46Ka deliver broadband SATCOM connectivity in minutes, thanks to their rapid roll-on/roll-off capability. With plug-and-play functionality and single-button activation, they are ideal for missions requiring rapid deployment and immediate operational readiness—even in GPS-denied or hostile environments.

The systems support GEO, MEO, LEO, and HEO satellite constellations, ensuring comprehensive global coverage. With high EIRP and G/T values and efficient EIRP Spectral Density (EIRPsd), they provide optimal performance with reduced bandwidth consumption—making them especially suitable for defense forces operating large SATCOM fleets.

Their ruggedized, MIL-STD-compliant construction enables reliable operation in extreme maritime conditions, while their compact footprint makes them a perfect fit for small vessels, where every inch of space matters.

“Modern naval operations increasingly rely on unmanned and small platforms that still require robust connectivity,” said Daniel Eshchar, CEO of Orbit. “The MPT30Ka and MPT46Ka rapid deployable systems bring advanced SATCOM capabilities to even the most compact maritime systems, ensuring operational effectiveness and mission continuity.”

About Orbit Communication Systems:

Orbit Communication Systems, a global leader in ground, airborne and maritime communications, satellite tracking, and ground-station technology, revolutionizes global connectivity with cutting-edge solutions for the new space era. Our state-of-the-art systems are utilized on a wide range of platforms, including mission aircraft, trainers, rotary-wing aircraft, transport vessels, tankers, jet fighters and unmanned platforms. Our reach extends to naval vessels, armored land platforms, cruise ships, ground stations, and offshore platforms, ensuring comprehensive coverage across maritime and terrestrial domains.

Orbit provides innovative, cost-effective, and reliable solutions to commercial operators, major air forces, navies, space agencies, and emerging New Space companies. Orbit is publicly traded on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange and is under the control of the FIMI Investment Fund. The company maintains a subsidiary in Florida, USA, which provides production, integration, and support capabilities for the North American market. Its global operations, encompassing marketing, sales, and customer service, extend across Europe, and the Far East.

Featured image: Orbit’s MPT30Ka Deployable SATCOM System