By Robbin Laird

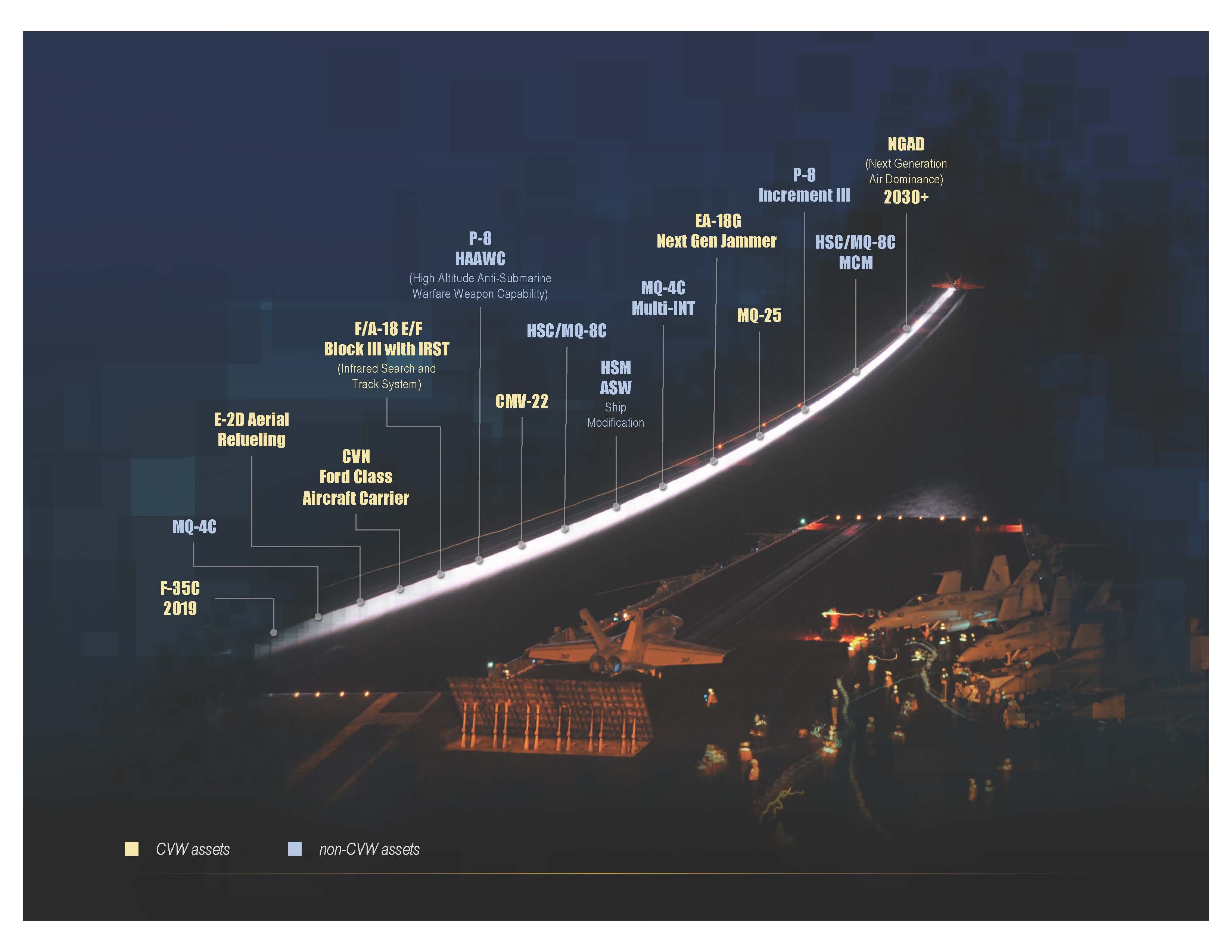

The US Navy over the next decade will reshape its carrier air wing (CVW) with the introduction of a number of new platforms.

If one simply lists the initial operating capabilities of each of these new platforms, and looked at their introduction sequentially, the “air wing of the future” would be viewed in additive terms – what has been added and what has been subtracted and the sum of these activities would be the carrier air wing of the future.

But such a graphic and such an optic would miss the underlying transformation under way, one which is highly interactive with the USMC and the USAF.

A case in point is the coming of the F-35C to the carrier wing.

One could discuss the difference between 4th and 5thgeneration aircraft, and the importance of the fifth-generation aircraft, already operating from amphib decks with the USMC, but it is much more than that.

Such a focus would be limited to what I have called F-35 1.0, namely, simply bringing the aircraft to the force and sorting through how to support it.

But the US Navy is focused directly on F-35 2.0 which is how to leverage the aircraft to transform the combat force into the integrated distributed force.

The coming of the F-35 is a trigger point for a significant remake of the CVW.

The entire process is rethinking the building, operations, transformation, and interaction of the F-35 (and not just operating from the carrier but working with other F-35s in the joint and allied forces) with the core Naval combat force to be able to generate concentrated combat power at the point of interest needed in a crisis.

One clearly needs a different optic or perspective than simply taking an additive approach.

And the graphic above highlights a way to think about the process of transformation for the carrier air wing over the next decade.

What is underway is a shift from integrating the air wing around relatively modest and sequential modernization efforts for the core platforms to a robust transformation process in which new assets enter the force and create a swirl of transformation opportunities, challenges, and pressures.

How might we take this new asset and expand the reach and effectiveness of the carrier strike group?

How might it empower maritime, air, and ground forces as we shape a more effective (i.e. a more integratable) force?

During a recent visit to San Diego, I had a chance to discuss such an evolving perspective with the Navy’s Air Boss, Vice Admiral “Bullet” Miller.

We started by discussing the F-35 which for him is a major forcing function change in the CVW.

But his focus is clearly upon not simply introducing the aircraft into the force but ensuring that it is part of the launch of a transformative process for shaping the evolving air wing or what I call F-35 2.0.

The F-35 is coming to the force after a significant investment and work by the US Navy to rebuild its operational capabilities after several years of significant sustainment challenges.

But now the Air Boss is looking to focus his attention on enhanced combat lethality which the fleet can deliver to the maritime services and the joint force.

What is being set in motion is a new approach where each new platform which comes into the force might be considered at the center of a cluster of changes.

The change is not just about integrating a new platform in the flight ops of the carrier.

The change is also about how the new platform affects what one can do with adjacent assets in the CSG or how to integrate with adjacent U.S. or allied combat platforms, forces, and capabilities.

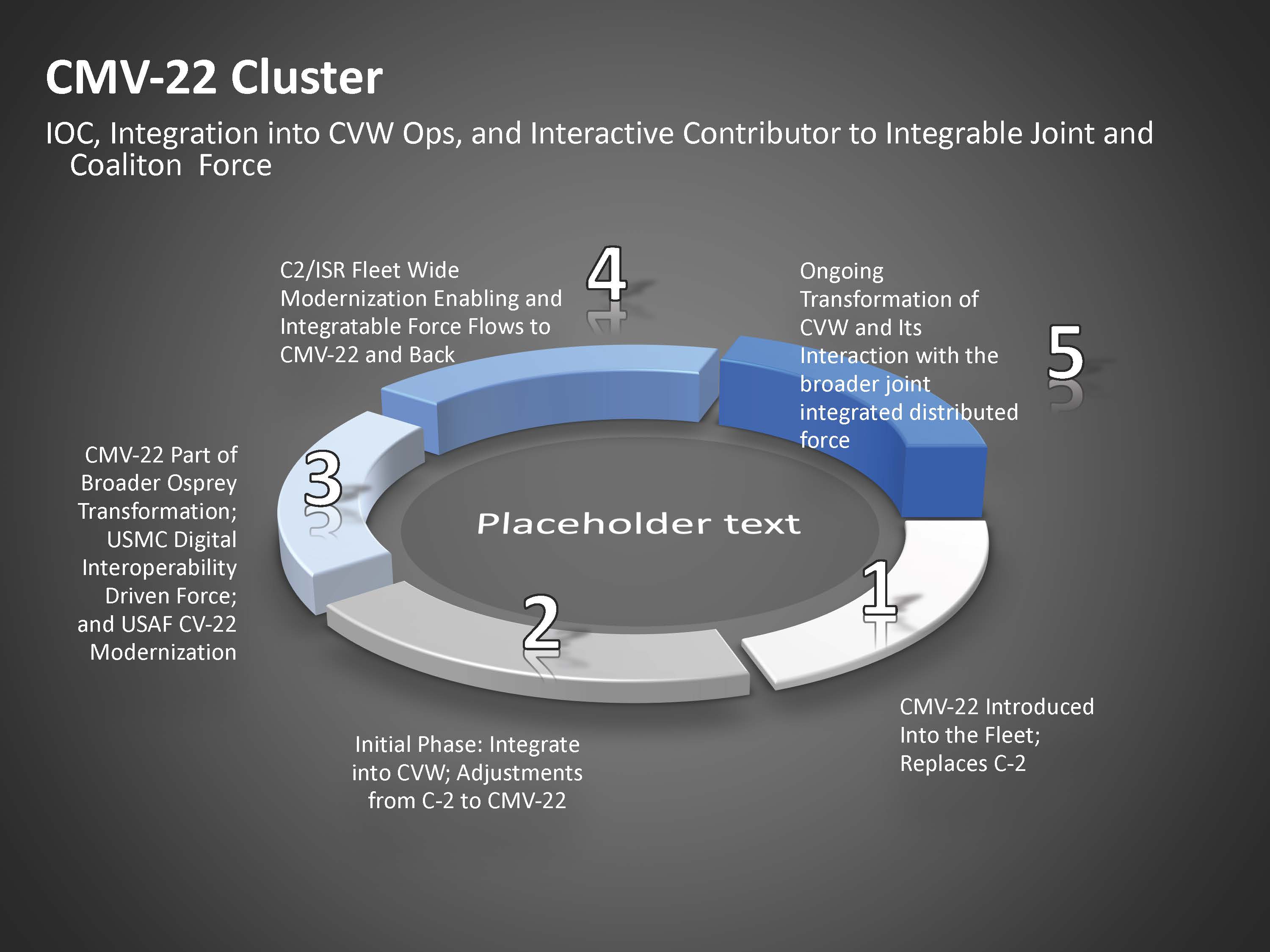

To give an example, the U.S. Navy is replacing the C-2 with the CMV-22 in the resupply role.

But the Navy would be foolish to simply think in terms of strictly C-2 replacement lines and missions.

So how should the Navy operate, modernize, and leverage its Ospreys?

For Miller, the initial task is to get the Osprey onboard the carrier and integrated with CVW operations.

But while doing so, it is important to focus on how the Osprey working within the CVW can provide a more integrated force.

Vice Admiral Miller and his team are looking for the first five-year period in operating the CMV-22 for the Navy to think through the role of the Osprey as a transformative force, rather than simply being a new asset onboard a carrier.

Hence, one can look at the CMV-22 innovation cluster in the following manner:

Such an approach is embedded in the rethink from operating and training an integrated air wing to an integratable air wing.

Vice Admiral Miller provided several other examples of how this shift affects the thinking about new platforms coming onboard the carrier deck.

One such example is the new unmanned tanker, the MQ-25.

The introduction of this new air asset will have an immediate effect in freeing up 4th gen fighters, currently being used for tanking, to return to their strike role.

Even more importantly from a transformation perspective, the MQ-25 will have operational effects as a platform which will extend the reach and range of the CVW.

But MQ-25 will be a stakeholder in the evolving C2/ISR capabilities empowering the entire combat force, part of what, in my view, is really 6th generation capabilities, namely enhancing the power to distribute and integrate a force as well as to operate more effectively at the tactical edge.

The MQ-25 will entail changes to the legacy air fleet, changes in the con-ops of the entire CVW, and trigger further changes with regard to how the C2/ISR dynamic shapes the evolution of the CVW and the joint force.

The systems to be put onto the MQ-25 will be driven by overall changes in the C2/ISR force.

These changes are driving significant improvements in size, capability, and integration, so much so that it is the nascent 6th gen.

This means that the USN can buy into “6thgen” by making sure that the MQ-25 can leverage the sensor fusion and CNI systems on the F-35 operating as an integrated force with significant outreach.

It is important to realize that a four ship formation of an F-35 operating as an integrated man-machine based sensor fusion aircraft is can operate together as a four ship pack fully integrated through the CNI system, and as such can provide a significant driver of change to the overall combat force.

This affects not only the future of training, but how operations, training, and development affect individual platforms once integrated into the CVW and larger joint force.

This will have a significant impact on Naval Air Warfare Development Center (NAWDC) based at Fallon.

A key piece in shaping the integratable air wing is building out a new training capability at Fallon and a new set of working relationships with other U.S. and allied training centers.

Later this year, we will visit Fallon and provide more details on the evolving approach.

The head of Fallon, Rear Admiral Richard Brophy, joined the conversation with the Air Boss, and clearly underscored the challenge: “How do we best train the most lethal integrated air wing preparing to deploy, but at same time, prepare for the significant changes which introducing new platforms and concepts of operations can bring to the force?

As the Air Boss put it: “We need to properly train the integratable airwing and we are investing in expanded ranges and new approaches such as Live Virtual Constructive training.

“I often use the quote that ‘your performance in combat never raises to the level of your expectations but rather it falls to the level of your training.’

“This is why the training piece is so central to the development for the way ahead for the integrable training.

“It is not just about learning what we have done; but it is working the path to what we can do.”

Consider the template of training for CVW Integration.

On the one hand, the CVW trained at Fallon needs to prepare to go out into the fleet and deliver the capabilities that are available for today’s fight.

On the other hand, as this template is executed, it is important to shape an evolving vision on how to operate platforms coming to the fleet or how those assets have already been modified by software upgrades.

A software upgradeable fleet, which is at the heart of the 5th gen transition and which lays down the foundation for 6th generation c2/ISR provides a key challenge.

The F-35 which operated from the last carrier cycle, or flew with the P-8 or Triton, all of these assets might well have new capabilities delivered by the software development cycle.

How to make certain that not just the air wing, but the commanders at sea fully understand what has changed.

The challenge is to shape the template for training today’s fleet; and to ensure that the template being shaped has an open aperture to handle the evolution of the CVW into the evolving integrated and distributed force.

Two measures of the change in the shift from the integrated to the integratable CVW which we discussed are the question of how to measure the readiness of a fifth-generation aircraft and the second is the creation of a new patch in Fallon, which builds upon the lessons learned during the early TOPGUN days.

The first is that aircraft readiness is a key measure of combat preparedness.

Rates of aircraft availability for a combat aircraft, can it fly or not is a baseline indicator of combat availability.

But for VADM Miller, the F-35 needs to be measured by a different standard given its key role in enabling an integratabtle CVW, namely full mission capability.

Can the aircraft fly with its full mission capability today?

This expectation reflects the F-35’s role as a flying combat system, mission manager, and sensor fusion generator for the air wing and strike group.

The second is the creation of the Maritime ISR or MISR patch.

MISR officers are trained as ISR subject matter experts to operate at the fleet or CSG level and to work the sensor fusion for the integratable CVW.

According to the Air Boss: “I think of MISR as additive, not lessening of TOPGUN, but instead akin to a new phase which builds upon our historical experience in the development of TOPGUN in the first place.”

In effect, these are “6th generation officers” in the sense of working the C2/ISR capabilities which enable an integrated and distributed fleet to have its maximum combat impact.

In short, the fleet is in the throes of significant transition.

The emergence and forcing function of an integrated CVW is at the heart of the transition.

And the emergence of a new patch at NAWDC certainly highlights the change.

Air to air combat skills remain important but now with your wingman miles away in a fifth generation aircraft context, or Aegis operating as your wingman, the C2/ISR revolution is highlighting the evolving capabilities of integration for combat dominance.1

The featured photo shows Vice Adm. DeWolfe H. Miller III, Commander, Naval Air Forces, speaking at the Fleet Logistics Multi-Mission Wing (COMVRMWING) 1 establishing ceremony on board Naval Air Station North Island (NASNI) Oct. 10. The Navy established its first CMV-22B Osprey squadron (VRM-30) Dec. 14,

Also see the earlier interview with Vice Admiral Miller:

In the Footsteps of Admiral Nimitz: VADM Miller and His Team Focused on 21st Century “Training”

And below is my briefing given at BIDEC 19 in Bahrain this past November on the emergence of the integrated distributed force: