By Pierre Tran

France has launched 18-month studies for a next-generation aircraft carrier to replace its Charles de Gaulle capital ship, Armed Forces Minister Florence Parly said.

“This step, which is being launched today, is the study step,” Parly said at the Oct. 23 opening of the Euronaval trade show. “It is to decide together what we want and how we want it for our future aircraft carrier.

“We give ourselves 18 months,” she said. The total cost of the studies was €40 million, she later added.

Chantiers de l’Atlantique, Naval Group and Technicatome will conduct the major part of the studies, with contributions from Dassault Aviation, Thales, MBDA, and other companies, government and industry sources said.

Total spending on the carrier program is estimated at €5 billion-€7 billion, business magazine Challenges reported. That cost estimate did not come from the ministry, a government official said.

An aircraft carrier is seen as a highly valued capability, with nations including China, India and Brazil keen to rachet up military power and prestige.

“An aircraft carrier is a symbol of power,” said François Lureau of consultancy EuroFLconsult and a former head of arms procurement. “It is highly visible. It is a political decision.”

The studies for the carrier would address issues such as what threats will be engaged and missions for the future carrier, Parly said. Responses to those questions would allow decisions on operational use, requirements for combat systems and the escort fleet. A second aspect is what technology will be available in 2030, she said. France has launched cooperation with Germany on the Future Combat Air System and the carrier will need to accommodate all capabilities of the planned fighter jet.

The ship’s propulsion, whether nuclear or conventional, will be considered, she said. Disruptive technology, such as electromagnetic aircraft catapults, should also be taken into account.

Cooperation with allies is another key factor, both in working on the vessel and the carrier receiving European partners’ aircraft, she said.

“This aircraft carrier could operate to the last decades of the 21st century, we cannot allow ourselves to design with a limited horizon,” she said. Innovation was vital, and the carrier could be “a true forward base for the Navy, a spur to our innovation,” she added.

Parly also said 18 Atlantique 2 would be modernized, three more units than previously planned, with all the upgraded maritime patrol aircraft delivered by 2025.

The Direction Générale de l’Armement procurement office signed Oct. 11 a contract with Dassault and Thales for modernization of six ATL2 aircraft. That deal follows a previous contract for upgrade of 12 MPA, the ministry said Oct. 23. The upgrade aims to boost the Navy’s capability against submarine threats, which are increasing around the world, particularly in areas of French strategic interest.

The upgrade includes fitting the Thales Searchmaster radar based on an active electronic array developed for the Rafale, as well as onboard tactical computer, electro-optical and acoustic sensors. The modernization is expected to extend the ATL2 life beyond 2030. The first two upgraded ATL2 are due to be delivered next year.

Parly also announced the planned construction of four fleet auxiliary tankers in cooperation with Italy, based on the Italian Vulcano vessels.

“This fleet is decisive,” she said, adding that the choice of Italy as partner reflected the will to boost Franco-Italian cooperation in surface ships.

The unit price for the four tankers was €430 million, a government official said.Naval Group and Chantiers de l’Atlantique will build the new tanker fleet, based on the Italian design, with the first two delivered to the French Navy by 2025, the ministry said in an Oct. 24 statement.

France, in cooperating with Italy, will join the Logistic Support Ship naval program managed by the OCCAR European arms procurement agency, the ministry said.

The French vessels will be modified to allow the tankers to support the Charles de Gaulle carrier task force and fitted with a Naval Group combat system. Fincantieri will build in Italy the hull sections with the refuelling system. The four double-hulled ships will replace the present three-strong tanker fleet, which have single hulls.

This article is republished with the permission of our partner, Operationnels SLDS.

The article was first published by OPS on October 25, 2018.

The featured photo shows President Macron at the Palace of Versailles in July 2017 to address both houses of the French parliament

ETIENNE LAURENT/GETTY IMAGES

Editor’s Note: Some Key Considerations Which Flow From Developing a New French Aircraft Carrier

The US and the UK have launched new aircraft carriers which are either in operation or about to be.

A key question will be the relationship of the French effort to those of the US and the UK?

Also, there are other countries building carriers of various sorts, including India, and in the case of Spain and Italy smaller ships which carry currently Harriers but will need a vertical lift aircraft, notably the F-35B, to operate as aircraft carriers.

What will be the relationship of the French approach to these other carrier nations?

A key question will be the development of the aircraft, rotorcraft and weapons among other things for any new French aircraft carrier.

The proposed Franc0-German joint new fighter would be affected as well by the need to operate that aircraft off of a carrier, something which the French have in mind, but not something the Germans are considering.

The Rafale was built initially to fly off of the Charles de Gaulle and was designed in part with this in mind, and joint Air Force and Navy operations of the same aircraft, albeit of different variants has been important to French military operations.

How would this legacy for Dassault affect the proposed working relationship with European industry to shape a next generation European combat aircraft?

In other words, if carrier aviation is considered important for France, how will they develop and fund such a capability?

Would this be done within or outside of the proposed Franc-German project?

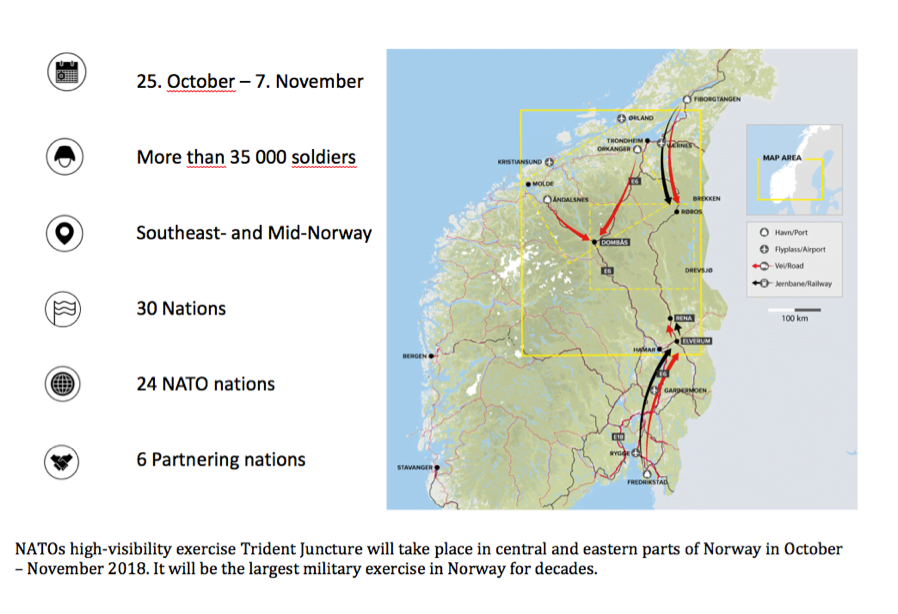

Col Lars Lervik at the Norwegian Ministry of Defence is working the preparation for the Trident Juncture 2018 exercise and according to him:

Col Lars Lervik at the Norwegian Ministry of Defence is working the preparation for the Trident Juncture 2018 exercise and according to him: