By Robbin Laird

The strategic shift is a crucial one for the liberal democracies.

That strategic shift is from a primary focus on counter insurgency and stability operations to operating in a contested environment with high tempo and high intensity combat systems as a primary tool set.

It is about managing conflict with peer to peer competitors.

On the one hand, the military capabilities are being reshaped to operate in such an environment, and there is a clear opportunity to leverage new platforms and systems to shape a military structure more aligned with the new strategic environment.

On the other hand, the civilian side of the equation needs even more significant change to get into the world of crisis management where hybrid war, mult-domain conflict and modern combat tools are used.

While preparing for large-scale conflict is an important metric, and even more important one is to reshape the capabilities of the liberal democracies to understand, prepare for, and learn how to use military tools most appropriate to conflict management.

This means putting the force packages together which can gain an advantage, but also learning how to terminate conflict.

Already we have seen two examples of crisis management using high intensity conflict forces under the Trump Administration, and both involved using military tools to degrade Syrian chemical weapons capabilities. The military strikes were the visible side of the effort; the back channel discussions with the allies and the Russians were the less visible one.

But crisis management of this sort is going to become the new normal, and rather than forming yet another committee of experts to lecture the Trump Administration on what Inside the Beltway thinks is proper behavior, it is time for some PhD brain power to be generated to deal with how to understand the new combat systems and how best to master these systems from a political military point of view to deliver significantly enhanced crisis management capabilities.

Recently, Paul Bracken provided some PhD brain power on the subject and he highlighted a key aspect of what I am calling the strategic shift to crisis management for 21stcentury peer-to-peer conflicts.

The key point for today is that there are many levels of intensity above counterinsurgency and counter terrorism, yet well short of total war. In terms of escalation intensity, this is about one-third up the escalation ladder.

Here, there are issues of war termination, disengagement, maneuvering for advantage, signaling, — and yes, further escalation — in a war that is quite limited compared to World War II, but far above the intensity of combat in Iraq and Afghanistan…..

A particular area of focus should be exemplary attacks.

Examples include select attack of U.S. ships, Chinese or Russian bases, and command and control.

These are above crisis management as it is usually conceived in the West.

But they are well below total war.

Each side had better think through the dynamics of scenarios in this space.

Deep strike for exemplary attacks, precise targeting, option packages for limited war, and command and control in a degraded environment need to be thought through beforehand.

The Russians have done this, with their escalate to deescalate strategy.

I recently played a war game where Russian exemplary attacks were a turning point, and they were used quite effectively to terminate a conflict on favorable terms.

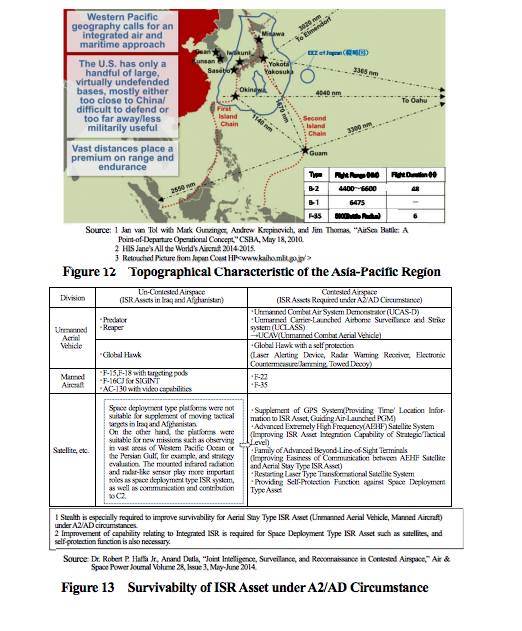

In East Asia, exemplary attacks are also important as the ability to track US ships increases.

Great power rivalry has returned.

A wider range of possibilities has opened up.

But binary thinking — that strategy is either low intensity or all-out war – has not.

I want to focus on the following Bracken observation: These are above crisis management as it is usually conceived in the West.

The point can be put bluntly – we need to rethink crisis management rather than simply thinking the strategic shift is from fighting terrorists to preparing for World War III and musing on how we will lose.

And that is a key area of work facing civilian strategists, but only if they understand that the new military capabilities open up opportunities as well for something more effective than simply doing nothing or very little or launching major combat operations.

Figuring out how to leverage the new capabilities and to build upon these in shaping scalable and agile force capabilities is part of what civilians need to learn with regard to how to think about tools for crisis management.

The other part is to think through a realistic assessment of how to work with authoritarian leaders who are our adversaries in the midst of a crisis so that conflict termination can be achieved but without following the Chamberlain model.

At the heart of this is a fundamental change to C2, both for the military and for the civilian leadership which is supposed to provide strategic guidance.

But simply identifying a geographical location to send the military and then failing to find a time when the return ticket can be issued is not effective leadership.

My recent visits with the Nordics highlight a region thinking through these kinds of issues.

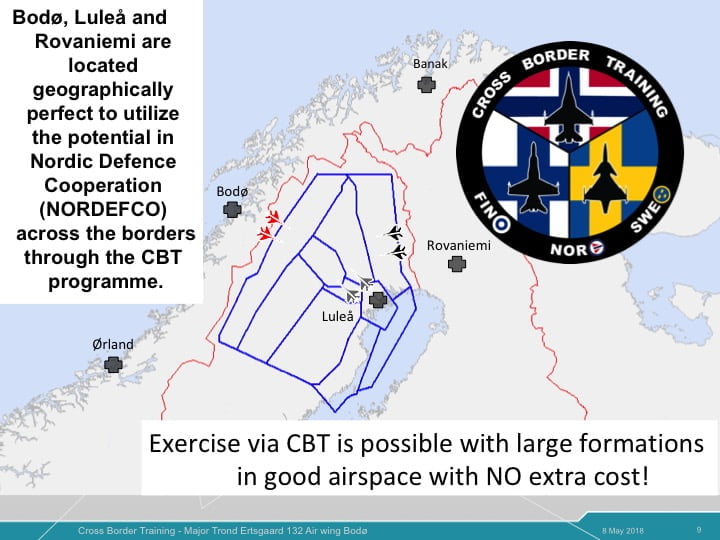

On the one hand, the enhanced military collaboration among the Nordics seen in things like Cross Border training or the coming Trident Juncture 2018 exercise in Norway is clearly about working through how to generate the combat power which can be tailored to a crisis.

On the other hand, the Nordics within the framework of NORDEFCO, or the working relationship with the United States as seen in the new trilateral agreement signed by the US, Sweden and Finland are examples of working through the civilian side of crisis management.

It is a work in progress and not one where the United States is clearly in the lead. Given that crises are regional, our allies have important contributions in shaping a way ahead to manage crises in their region as well.

And the Nordics are clearly doing this.

We need to rework our military C2; and even more importantly, put a rest to our civilian strategists simply campaigning for a place in the next Administration.

We do need to focus on how we can turn the Russian and Chinese anti-access and area denial strategies into a 21stcentury version of the Maginot Line. And we are already building systems and capabilities that can do so, but not without a transformation focus and effort.

But we need to learn to not self-deter and to explore ways to push the leaders of the non-liberal powers hard and to also understand how to engage with them as well.

This is neither the world of the High School Musical which the globalization folks seem to champion; nor the harsh world of zero sum conflict which hardliners to the right seem to live in.

It is a world where conflict and crisis management are the new normal between and among peer competitors.