2017-08-14 By Edward Timperlake and Robbin Laird

During our recent visit to Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center or NAWDC, Captain Leif “Weed” Steinbaugh, Director of Training at NAWDC, provided our first briefing which oriented us to the changes at NAWDC since we last visited Fallon Naval Air Station in 2014.

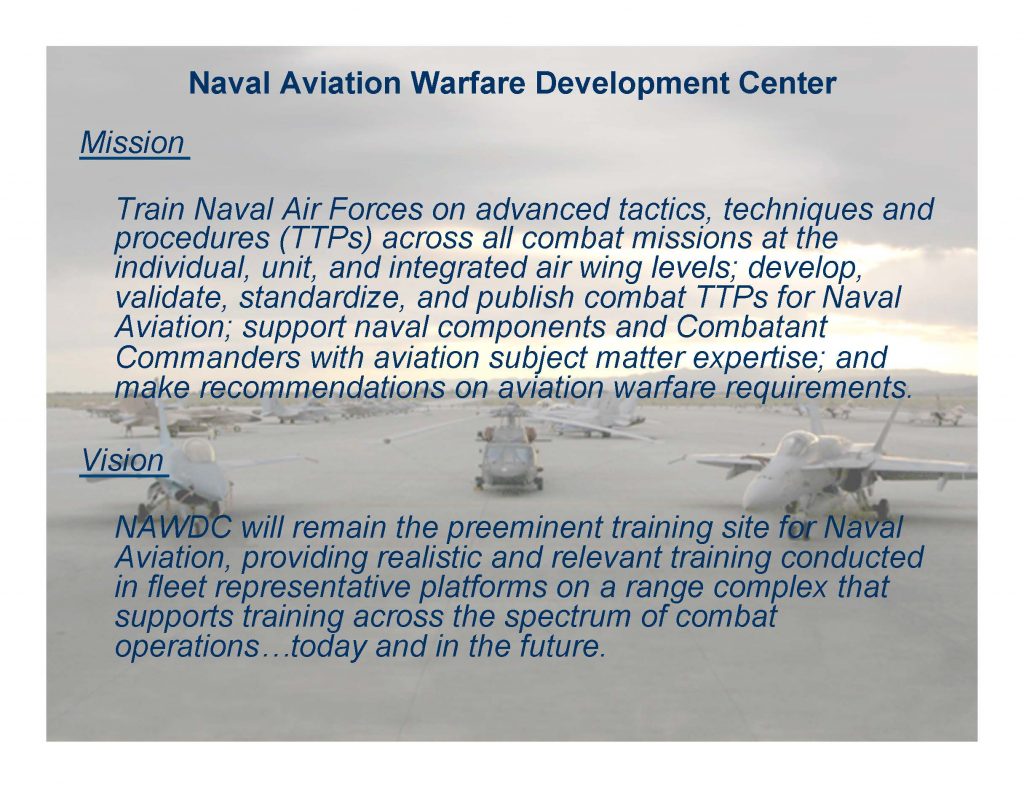

Notably, the name had changed from Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center (NSAWC) to the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWADC).

This change of name is very significant and represents a culmination of the work of the Top Gun era and the laying the foundation for the integrated Warfighting approach for the distributed fleet, which the US Navy is shaping with the fleet it has and the fleet, which is on the way.

Captain Steinbaugh has a significant background in Electronic Warfare and strike operations as well.

He first flew A-6s, then went to Prowler and then to Growler.

This is his fourth tour at Fallon as well. His first tour was with the strike department, the second he set up the Growler department and the third was in the training department.

Captain Steinbaugh characterized NSAWC as follows:

“The focus was on proficiency with the platform, at the individual level with integration in the final week of Air Wing Fallon.

“TTPs were approached from this perspective.

“Then as now we train the training officers for the Carrier Air Group or CAG.”

The name change reflects a strategic shift in the US Navy towards integrated Warfighting and, by definition almost, because integration is crucial to success, to an enhanced focus on the high end fight.

NAWDC was the first of a series of Warfighting development centers which have been stood up and which the Navy is leveraging for the evolution of the integrated Warfighting approach.

There are several Warfighting development centers: for surface and mine warfare, underwater warfare, for information warfare, for expeditionary warfare.

Currently, the closest working relationship between NAWDC and the other Warfighting centers is with the surface Warfighting development center, and with the potential to cross link aviation with the weapons onboard surface ships this lays a solid foundation to go where the technology is evolving as well.

There is a monthly video teleconference among the Warfighting development centers.

Warfare tactics instructors (WTI), from left to right, Lt. Cmdr. Mike Dwan, Lt Doug Wilkins, Lt. Lisa Schmidt, Lt Joseph Lewis, Lt Scott Margolis, Lt. Andrew Blanco, Lt Weston Floyd, LT Justin Bolly, Lt. Serg Samardzic, Lt. Rebecca O’Brien, and Lt. Cmdr. Derek Rader pause for a group photo at Naval Air Station (NAS) Fallon, in Nevada. The 11 integrated air and missile defense (IAMD) WTIs participated in a pilot integrated air defense course (IADC) — a joint effort led by the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) and Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC). IADC will activate in late 2016 and train carrier air wings, carrier strike groups, and air and missile defense commanders in a simulated training environment at NAS Fallon. Several IAMD WTIs will teach and train the inaugural course alongside their aviation counterparts from Navy Weapons Fighter School (TOPGUN).

Warfare tactics instructors (WTI), from left to right, Lt. Cmdr. Mike Dwan, Lt Doug Wilkins, Lt. Lisa Schmidt, Lt Joseph Lewis, Lt Scott Margolis, Lt. Andrew Blanco, Lt Weston Floyd, LT Justin Bolly, Lt. Serg Samardzic, Lt. Rebecca O’Brien, and Lt. Cmdr. Derek Rader pause for a group photo at Naval Air Station (NAS) Fallon, in Nevada. The 11 integrated air and missile defense (IAMD) WTIs participated in a pilot integrated air defense course (IADC) — a joint effort led by the Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) and Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center (NAWDC). IADC will activate in late 2016 and train carrier air wings, carrier strike groups, and air and missile defense commanders in a simulated training environment at NAS Fallon. Several IAMD WTIs will teach and train the inaugural course alongside their aviation counterparts from Navy Weapons Fighter School (TOPGUN).

“ We focus on TTP development and doctrine, on upcoming major exercises and any Commander interest items that the Commanders may have.

“The biggest change with the Warfighting Development Centers is our ability now to integrate with the other communities, and to gain a better understanding of the evolving mission areas.”

The culmination of the training process at NAWDC is Air Wing Fallon when the air wing about to go on deployment comes for its final training.

“Their training track, if you will, is to get ready for deployment.

“They will have completed the air wing, will have completed advanced readiness program, which is the program done by platform for each of their type of squadrons. We start where they should be, at what level they should be at, finishing ARP, and then we do a crawl, walk, run.

“The first week, week and a half, we give them the plan, we do everything for them.

“They don’t have to do any of the planning.

“They just have to execute.

“Once we see that they can execute, we’ll get to the next part where they get more involved in the planning, we tighten the timelines down a little bit on them so it provides some pressure.

“We up the game, if you will, on the threats side of things so things feel a bit more real, and finally the last week is ATP, the advanced training phase, where they are pretty much on a timeline.

“We may see out on deployment, whoever might be out there at the time and they then execute there.

“The threat is about as high as we can ramp it up to.”

Captain Steinbaugh highlighted what the training command is doing now but how the transition implied in the name change was laying the foundation for a way ahead towards more effective fleet integration.

With new buildings being added for simulation and training a new phase will be added.

We will focus on this shift in a later interview, but it is clear that the Navy is preparing for a more effective fleet operation with the fleet it has, but is taking the longer view of preparing for the potential for rapid innovation associated with the fleet operating in a kill web.

Captain Leif “Weed” Steinbaugh, Director of Training at NAWDC

Captain Steinbaugh is a native of Quantico, VA. He earned his commission in May 1990 from the United States Naval Academy, where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering.

He was designated a Naval Flight Officer in April 1992 and was assigned to Attack Squadron (VA) 128 for training as an A-6E Bombardier/Navigator. After completing training in July 1993, he was assigned to the “Boomers” of VA 165. While assigned to VA 165 as schedules officer and line division officer, he completed one Western Pacific/Arabian Gulf deployment and decommissioned the squadron in August 1996. He then was assigned to Commander, Medium Attack Wing, Pacific as part of the A-6E “Shoretail” detachment until the retirement of the A-6E. Selected for transition to the EA-6B Prowler, he reported to Electronic Attack Squadron (VAQ) 129 in December 1996 for training as an EA-6B Electronic Countermeasures Officer.

After graduating from VAQ 129 in January 1998, Captain Steinbaugh was assigned to the “Gauntlets” of VAQ 136 in Atsugi, Japan for a “Super-JO” tour. While with VAQ 136 as the personnel officer and assistant maintenance officer, he completed two Arabian Gulf deployments and numerous Western Pacific deployments. Promoted to Lieutenant Commander in August 2000, he was extended in VAQ 136 in order to complete his department head tour, serving as the squadron’s operations officer.

From January 2002 until January 2004, Captain Steinbaugh was assigned to VAQ 129 as the maintenance officer and as a fleet replacement squadron instructor. In January 2004, he was assigned to the Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center Strike Department as the electronic warfare division officer, where he instructed carrier air wings in Suppression of Enemy Air Defense tactics. Captain Steinbaugh was then assigned to the staff of Commander, Naval Air Forces, as the EA-6B/EA-18G Class Desk Officer from July 2005 to January 2007. He then proceeded to VAQ 129 for refresher training and reported in November 2007 to VAQ 131 as the executive officer. He assumed command of VAQ 131 in February 2009. In May 2010, he reported back to VAQ 129 for transition to the EA-18G.

Captain Steinbaugh reported to Naval Strike and Air Warfare Center in October 2010 as the first Airborne Electronics Attack Weapons School (HAVOC) Department Head. As a HAVOC plank owner, he helped develop and establish the classroom and flight syllabus for the Growler Tactics Instructor course.

In June 2013, he became the Commanding Officer of Naval Air Station Fallon. Captain Steinbaugh now serves as Director of Training at Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center, on Naval Air Station Fallon.

http://www.public.navy.mil/AIRFOR/nawdc/Pages/Director%20of%20Training.aspx

Appendix: The Structure of NAWDC

NAWDC’s individual mission requirements include:

N2: The Information Warfare Directorate at NAWDC is responsible for ensuring command leadership and personnel are provided the full capabilities of the Information Warfare Community (IWC) to support combat readiness and training of Carrier Air Wings and Strike Groups. The Directorate is comprised of four areas of focus: Air Wing Intelligence Training, the Maritime ISR (MISR) Cell, Targeting, and Command Information Services (CIS).

The Air Wing Intelligence Training Division is responsible for training CVW Intelligence Officers and Enlisted Intelligence Specialists in strike support operations. The MISR Cell is tasked with providing ISR integration into Carrier Air Wing training as well as qualifying MISR Package Commanders and Coordinators. The Targeting Division trains and certifies all CVW Targeteer personnel and provides distributed reach-back support for deployed units worldwide regarding target development. CIS provides cyber security and computer network operations for the entire NAWDC enterprise.

N3: NAWDC Operations department (N3) is responsible for the coordination, planning, synchronization, and scheduling for the operations of the command, its assigned aircraft, and airspace and range systems within the Fallon Range Training Complex (FRTC).

N4: NAWDC’s Maintenance Department is the heart of training for all the NAWDC schoolhouses. Maintenance’s focus is providing mission-ready fleet and adversary aircraft configured with required weapons and systems for all training evolutions. We support day to day training missions with the F-16 Viper, F-18 Hornet and Super Hornet, EA-18G Growler, E-2C Hawkeye and the MH-60S Seahawk; conducting scheduled and un-scheduled maintenance on 39 individual aircraft. These aircraft and weapon systems are the foundation for all other NAWDC Department’s training syllabi.

N5: Responsible for training Naval aviation in advanced Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTP) across assigned combat mission areas at the individual, unit, integrated and joint levels, ensuring alignment of the training continuum; to set and enforce combat proficiency standards; to develop, validate, standarize, publish and revise TTPs.

Also provides subject matter expertise support to strike group commanders, numbered fleet commanders, Navy component commanders and combatant commanders; to lead training and warfighting effectiveness assessments and identify and mitigate gaps across all platforms and staffs for assigned mission areas as the supported WDC; and collaborates with other WDCs to ensure cross-platform intergration and alignment.

NAWDC’s Joint NAWDC’s Joint Close-Air Support (JCAS) Division continues to answer the needs of current theater operations with increased production of Joint Terminal Attack Controllers Course (JTACC).NAWDC’s Joint NAWDC’s Joint Close-Air Support (JCAS) Division continues to answer the needs of current theater operations with increased production of Joint Terminal Attack Controllers Course (JTACC). NAWDC JCAS primarily trains Naval Special Warfare and Riverine Group personnel, but has this year also trained U.S. Army Special Operations, U.S. Marine Corps Air and Naval Gunfire Liaison Officers, international personnel, as well as U.S. Navy Fixed and Rotary Wing Forward-Air Controller (Airborne) personnel.

NAWDC’s JCAS branch is the U.S. Navy’s designated representative to the Coalition JCAS Executive Steering Committee, and is a recognized authority on kinetic air support to information warfare (IW), tactical precision targeting, and digitally aided CAS.

N6: Carrier Airborne Early Warning Weapons School (CAEWWS), also referred to as TOP DOME, is the E-2 weapon school and responsible for Airborne Tactical Command and Control advanced individual training via the Hawkeye Weapons and Tactics Instructors (HEWTIs) class. CAEWWS is also responsible for development of community Tactics, Technique and Procedures and provides inputs to the acquisition process in the form of requirements and priorities for research and development (R&D), procurement, and training systems.

CAEWWS works closely to support other Warfare Development Centers and Weapons Schools; such as the Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center’s Integrated Air Defense Course (IADC) and Integrated Air and Missile Defense WTI Integration Course (IWIC). Other functions include support to advanced integrated fleet training by way of WTI augmentation to the N5/STRIKE Department for CVW integrated training detachments; also known as Air Wing Fallon Detachment and support of squadron activities.

N7: In the early stages of the Vietnam War, the tactical performance of Navy fighter aircraft against seemingly technologically inferior adversaries, the North Vietnamese MiG-17, MiG-19, and MiG-21, fell far short of expectations and caused significant concern among national leadership.

Based on an unacceptable ratio of combat losses, in 1967, ADM Tom Moorer, Chief of Naval Operations, commissioned an in-depth examination of the process by which air-to-air missile systems were acquired and employed. Among the multitude of findings within this report was the critical need for an advanced fighter weapons school, designed to train aircrew in all aspects of aerial combat including the capabilities and limitations of Navy aircraft and weapon systems, along with those of the expected threat.

In 1969, the United States Navy Fighter Weapons School (TOPGUN) was established to develop and implement a course of graduate-level instruction in aerial combat. Today, TOPGUN continues to provide advanced tactics training for FA-18A-F aircrew in the Navy and Marine Corps through the execution of the Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor (SFTI) Course. TOPGUN is the most demanding air combat syllabus found anywhere in the world. The SFTI Course ultimately produces graduate-level strike fighter tacticians, adversary instructors, and Air Intercept Controllers (AIC) who go on to fill the critical assignment of Training Officer in fleet units.

N8: Navy’s Rotary Wing Weapons School is composed of a staff of 25 pilots and aircrewmen who instruct the Seahawk Weapons and Tactics Instructor program; provide tactics instructors to fleet squadrons; maintain and develop the Navy’s helicopter tactics doctrine via the SEAWOLF Manual; instruct the Navy’s Mountain Flying School; provide high-altitude, mountainous flight experience for sea-going squadrons; and provide academic, ground, flight, and opposing-forces instruction for visiting aircrew during Air Wing Fallon detachments.

N9: The NAWDC Safety Department (N9) serves as the principle advisor to the Commander on all matters pertaining to safe command operations and is responsible for administering the following safety programs: aviation, ground, ergonomics, motor vehicles (personal, commercial), recreation, and on- and off-duty. Our goal is to eliminate preventable mishaps while maximizing operational readiness. We accomplish this by preserving lives, preventing injury, and protecting equipment and material.

N10: The US Navy’s Airborne Electronic Attack Weapons School, call sign “HAVOC”, stood up in 2011 to execute the NAWDC mission as it pertains to Electronic Warfare and the EA-18G Growler. HAVOC is comprised of highly qualified Growler Tactics Instructors, or GTIs, that form the “tactical engine” of the EA-18G community, developing the tactics that get the most out of EA-18G sensors and weapons. HAVOC’s mission is also to train Growler Aircrew and Intelligence Officers on those tactics during the Growler Tactics Instructor Course.

The Growler Tactics Instructor Course is a rigorous 12 week syllabus of academic, simulator, and live fly events that earn graduates the Growler Tactics Instructor designation – the highest level of EA-18G tactical qualification that is recognized across Naval Aviation. The Growler brings the most advanced tactical Electronic Warfare capabilities to operational commanders creating a tactical advantage for friendly air, land, and maritime forces by delaying, degrading, denying, or deceiving enemy kill chains.

N20: The Tomahawk Landing Attack Missile (TLAM) Department provides direct support to U.S. Fleet Forces Command (USFFC) in the development and standardization of tactics, techniques and procedures for the employment of the Tomahawk weapon system. In addition, TLAM provides training to the CVW, fleet, and joint commands on TLAM capabilities and strike integration

https://www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrsw/installations/nas_fallon/about/nawdc.html

U.S. Air Force members from the 169th Fighter Wing and South Carolina Air National Guard are deployed to Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada Fallon to support Naval Carrier Air Wing One with pre-deployment fighter jet training, integrating the F-16’s suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) capabilities with U.S. Navy fighter pilots. (U.S. Air National Guard photo by Tech. Sgt. Caycee Watson) September 2016

U.S. Air Force members from the 169th Fighter Wing and South Carolina Air National Guard are deployed to Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada Fallon to support Naval Carrier Air Wing One with pre-deployment fighter jet training, integrating the F-16’s suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD) capabilities with U.S. Navy fighter pilots. (U.S. Air National Guard photo by Tech. Sgt. Caycee Watson) September 2016 FALLON, Nev. (Sept. 3, 2015) F-35C Lightning IIs, attached to the Grim Reapers of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 101, and an F/A-18E/F Super Hornets attached to the Naval Aviation Warfighter Development Center (NAWDC) fly over Naval Air Station Fallon’s (NASF) Range Training Complex. VFA 101, based out of Eglin Air Force Base, is conducting an F-35C cross-country visit to NASF. The purpose is to begin integration of F-35C with the Fallon Range Training Complex and work with NAWDC to refine tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP) of F-35C as it integrates into the carrier air wing. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. Cmdr. Darin Russell/Released)

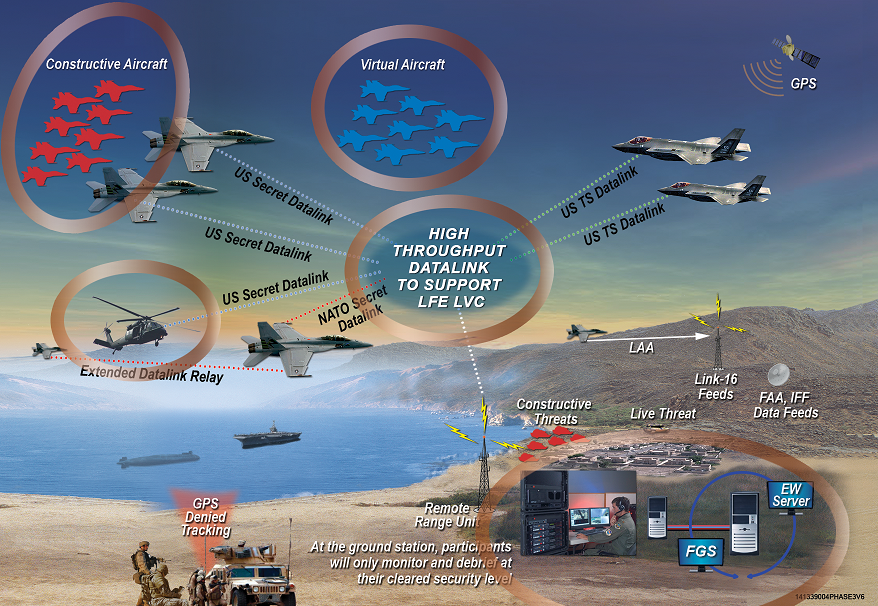

FALLON, Nev. (Sept. 3, 2015) F-35C Lightning IIs, attached to the Grim Reapers of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 101, and an F/A-18E/F Super Hornets attached to the Naval Aviation Warfighter Development Center (NAWDC) fly over Naval Air Station Fallon’s (NASF) Range Training Complex. VFA 101, based out of Eglin Air Force Base, is conducting an F-35C cross-country visit to NASF. The purpose is to begin integration of F-35C with the Fallon Range Training Complex and work with NAWDC to refine tactics, techniques and procedures (TTP) of F-35C as it integrates into the carrier air wing. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. Cmdr. Darin Russell/Released) http://www.abdonline.com/news-analysis/defense/better-training-virtually/#.VGC_y1PF9OF

http://www.abdonline.com/news-analysis/defense/better-training-virtually/#.VGC_y1PF9OF